The Harvard EdCast

Filter Results

How Schools Make Race

UCLA's Laura Chávez-Moreno discusses how bilingual education programs influence the racialization of Latinx students

The Untold Truths of the Superintendency

The challenges of being a superintendent, and how to attract, support, and retain leaders

Think You’re Creative? Think Again.

Project Zero's Edward Clapp explains the participatory approach to creativity, and how it can empower students by validating their contributions and helping them develop purpose in the world

The Problem Schools Are Ignoring

Strategies for educators and families to recognize, report, and prevent incidents of sexual misconduct in schools

Fixing Childcare in America

Child and family policy expert Elliot Haspel, Ed.M.'09, discusses the challenges and potential solutions for universal childcare in the United States

Boys and the Crisis of Connection

Alum Niobe Way discusses the crisis of connection among boys and young men, focusing on how societal norms about masculinity suppress emotional vulnerability and deep friendships

The Impact of AI on Children's Development

AI designed with certain principles in mind can benefit children's growth and learning, says Assistant Professor Ying Xu, but AI literacy is essential

Teaching the Election in Politically Charged Times

Lecturer Eric Soto-Shed advises against avoiding classroom discussions on the upcoming U.S. election — and, instead, offers strategies on making these conversations worthwhile

Summer Unplugged

Navigating screen time and finding balance for kids

Reshaping Teacher Licensure: Lessons from the Pandemic

Olivia Chi, Ed.M.'17, Ph.D.'20, discusses the ongoing efforts to ensure the quality and stability of the teaching workforce

Discipline in Schools: Why is Hitting Still an Option?

A pediatrician discusses the prevalence and effects of corporal punishment in schools, and what it might take to end it for good

Combatting Chronic Absenteeism with Family Engagement

As post-COVID absenteeism rates continue unabated, a look at how strong family-school engagement can help

Getting to College: FAFSA Challenges for First-Gen Students

The hurdles faced by first-generation college students as they make their way through the financial aid process — and how to help them overcome the barriers

Math, the Great (Potential) Equalizer

How current practices in math education around tracking and teaching can be dismantled to achieve the promise of equity in math classrooms

Why Emotional Intelligence Matters for Educators

Social-emotional skill-building for leaders can change the culture of a school — for the better

The Movements Making Change in Public Schools

The current influence of mom groups could shape the future of education

Improving Mental Health Through Independent Play

Psychologist Peter Gray discusses how encouraging independent play fosters resilient, self-reliant, and mentally fit young people

Navigating Literacy Challenges, Fostering a Love of Reading

With ongoing debates around the best ways to teach reading, what makes for truly effective literacy instruction?

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts , Spotify , Google Podcasts , or Amazon Music Stream all past episodes on Simplecast

Contact host Jill Anderson for information or to submit a guest proposal.

The opinions expressed in the Harvard EdCast are those of the guest alone, and not the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Our theme music is by The Void Union.

As education in the United States has evolved over the years, one consistent – and significant – factor has been anti-Black racism. Centuries of slavery and oppression led to a dual school system in which Black Americans were systematically denied access to quality education. The landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, famously declared that “separate is not equal,” but generations of Black Americans both before and after this decision were forced to defy laws and structural barriers to receive an education even close to equal.

Between 1740 and 1867, anti-literacy laws in the United States prohibited enslaved, and sometimes free, Black Americans from learning to read or write. White elites viewed Black literacy as a threat to the institution of slavery – it facilitated escape, uprisings, and the sharing of information and ideas among enslaved people. Indeed, literacy undermined the false foundation slavery was built on: the intellectual inferiority and inhumanity of African-descended people. The small percentage of enslaved people who became literate did so at great risk – those who were caught were often violently punished, sold, or even killed. Because of the danger, enslaved people had to be strategic and resourceful in learning to read and write. They attended secret informal schools taught by free Blacks at night, covertly learned from white enslavers’ children, or found opportunities when enslavers were away. Northern states were little better. Black education was generally viewed with suspicion and suppressed through legislation and threat of violence. For instance, when white schoolteacher Prudence Crandall opened a boarding school for Black girls in 1832 Connecticut, the state promptly passed a law requiring written permission from town officials for anyone seeking to teach Black students from other states. This empowered anti-Black racism on a local level and, facing escalating harassment and vandalism, Crandall closed the school after only two years. After the Civil War, emancipated Black Americans who’d been denied educational access for centuries made learning a priority. They established schools at their own expense and advocated for universal public education. The development of Southern public schools for students of all races is indebted to Black voters and legislators of the Reconstruction era. Education was embraced as a safeguard of Black liberation, self-determination, and rights as citizens.

Unfortunately, strides made during this era were cut short by racism and white supremacy.

Southern schoolhouses and teachers, regardless of race, were targets of racist violence. Between 1864 and 1876, over 630 southern Black schools were significantly damaged or destroyed. Black Americans who moved to Northern urban centers, meanwhile, were segregated by anti-Black laws, policies, and cultural practices that denied them equitable access to schools.

Across the country, state governments used their power to reinforce school segregation and to fund white schools at the expense of Black ones. Black students were left with dilapidated school buildings, fewer teachers and programs, and limited curriculum options. Facing these injustices, Black educators countered by receiving exceptional academic credentials to provide Black students with quality education. Although Brown v. Board of Education ended legal segregation in public schools, it did not end racial inequality in education. Freedom of Choice plans, private school vouchers, and white flight into suburbs perpetuated segregation and further concentrated wealth and school resources into predominantly white areas. In addition, many federal rulings after the Brown decision dismantled desegregation policies and strategies, and public schools today remain highly segregated by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Black students face an uphill battle against a system built on centuries of racism, divestment, and denied opportunities. Improved educational outcomes for Black students today can only be achieved by addressing these historic, race-based inequities.

Explore a curated sample of Harvard research and resources related to anti-Black racism in education below.

Fugitive pedagogy: carter g. woodson and the art of black teaching (harvard key only).

African Americans pursued education through clandestine means, often in defiance of law and custom, even under threat of violence in a tradition of “fugitive pedagogy.” This book examines this tradition through the efforts of educator, historian, and Black History Month founder Carter G. Woodson.

Teaching White supremacy: America's democratic ordeal and the forging of our national identity (Harvard Key Only)

This book explores white supremacy's deep-seated roots in the U.S. education system through an in-depth examination of American textbooks and the systematic ways in which white supremacist ideology has infiltrated American culture.

Teaching the Hard Histories of Racism

This article outlines five principles to guide educators in teaching difficult topics, such as racism and colonialism, to students of all ages.

Three Essays on Educational Policy and Equity

The systematic oppression of Black people throughout U.S. history has resulted in persistent unequal access to opportunity but decades of educational reform have not meaningfully reduced racial differences in standardized test performance, college going, or adult outcomes. This doctoral dissertation leverages rigorous quantitative research methods to contribute to and build on existing efforts to address racial inequalities through educational policy.

The Lingering Legacy of Redlining on School Funding, Diversity, and Performance

Between 1935-1940 the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) assigned A (minimal risk) to D (hazardous) grades to neighborhoods that reflected their lending risk from previously issued loans and visualized these grades on color-coded maps, which arguably influenced banks and other mortgage lenders to provide or deny home loans within residential neighborhoods. This working paper leverages a spatial analysis of 144 HOLC-graded core-based statistical areas (CBSAs) to understand how HOLC maps relate to current patterns of school and district funding, school racial diversity, and school performance.

The School to Prison Pipeline: Long-Run Impacts of School Suspensions on Adult Crime

Schools face important policy tradeoffs in monitoring and managing student behavior. Strict discipline policies may stigmatize suspended students and expose them to the criminal justice system at a young age. This working paper estimates the net impact of school discipline on student achievement, educational attainment and adult criminal activity and finds that the negative impacts of attending a high suspension school are largest for males and minorities.

United States District Court (Massachusetts) National Archives and Records Administration (U.S.) Tallulah Morgan et al. v. James W. Hennigan et al. Case File. 1972-1995

In 1972 fifteen parents filed a class action lawsuit alleging that the Boston School Committee violated the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution by a deliberate policy of racial segregation in Boston Public Schools. In 1974 Judge W. Arthur Garrity, Jr. found the Boston School Committee had intentionally carried out a program of segregation in the Boston Public Schools.This digitized archival collection is a facsimile of the civil action case file for Tallulah Morgan et al. v. James W. Hennigan et al. It contains documents related to the class action lawsuit, Garrity's decision, and implementation of court-ordered desegregation in Boston Public Schools.

Papers of Charlotte Hawkins Brown, 1900-1961

Educator Charlotte Eugenia Hawkins Brown was founder of the Palmer Memorial Institute in Sedalia, North Carolina, and active in the National Council of Negro Women and the North Carolina Teachers Association. She was the first Black woman to serve on the national board of the YWCA. She lectured and wrote about Black women, education, and race relations. This archival collection provides information about Charlotte Hawkins Brown's life and activities, the Palmer Memorial Institute, and Brown's continuing struggle to enlarge the school, the financial problems she encountered, and her constant fundraising efforts.

Education Now: Navigating Tensions Over Teaching Race and Racism

How can schools, educators, and families navigate the continued politicization and tensions around teaching and talking about race, racism, diversity, and equity? In this webinar panelists discuss what educators and families can do to make sure students are supported, learning, and prepared with the knowledge they need to understand their own histories and the diverse and global society they’ll enter.

Donald Yacovone, 'Teaching White Supremacy'

In this seminar historian Donald Yacovone discusses his book "Teaching White Supremacy: America’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National Identity" which explores white supremacy's deep-seated roots in the U.S. education system through an in-depth examination of American textbooks and the systematic ways in which white supremacist ideology has infiltrated American culture.

Harvard EdCast: The State of Critical Race Theory in Education

In this podcast educational researcher and pedagogical theorist Gloria Ladson-Billings discusses how she adapted Critical Race Theory from law to explain inequities in education, the current politicization and tension around teaching about race in the classroom, and offers a path forward for educators eager to engage in work that deals with the truth about America’s history.

Harvard EdCast: Fugitive Pedagogy in Black Education

The history of Black education is complex and rich, but often remains untold. In this podcast interdisciplinary historian Jarvis Givens explains how Black educators worked together to push back against oppressive school structures in a tradition of “fugitive pedagogy” that was passed down from generation to generation of Black educators.

Harvard EdCast: Schooling for Critical Consciousness

What is the role of schools in teaching students, especially students of color, how to face oppression and develop political agency? In this podcast Daren Graves and Scott Seider, authors of "Schooling for Critical Consciousness" (2020), share the ways that educators and school leaders can help young people better understand and challenge racial injustices.

Citations for Section Overview

- Anderson, James D. 2010. The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935 . Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. http://muse.jhu.edu/book/43951 .

- Ansalone, George. 2009. “Tracking, Schooling and the Equality of Educational Opportunity.” Race, Gender & Class 16 (3/4): 174–84.

- Caldera, Altheria. 2020. “Eradicating Anti-Black Racism in U.S. Schools: A Call-to-Action for School Leaders.” Diversity, Social Justice, and the Educational Leader 4 (1). https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/dsjel/vol4/iss1/3 .

- Dumas, Michael J. 2014. “Contesting White Accumulation in Seattle: Toward a Materialist Antiracist Analysis of School Desegregation.” In The Pursuit of Racial and Ethnic Equality in American Public Schools . Michigan State University Press. https://hollis.harvard.edu/permalink/f/1mdq5o5/TN_cdi_jstor_books_j_ctt13x0p5t_24 .

- Dumas, Michael J. 2016. “Against the Dark: Antiblackness in Education Policy and Discourse.” Theory Into Practice 55 (1): 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1116852 .

- Erickson, Ansley T., and Ernest Morrell. 2019. Educating Harlem: A Century of Schooling and Resistance in a Black Community . New York: Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/eric18220 .

- Feagin, Joe R, and Bernice McNair Barnett. 2004. “Success and Failure: How Systemic Racism Trumped the Brown V. Board of Education Decision.” UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LAW REVIEW 2004 (5): 32.

- Fenwick, Leslie T. 2022. Jim Crow’s Pink Slip: The Untold Story of Black Principal and Teacher Leadership . Race and Education Series. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Givens, Jarvis R. 2021. Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching . Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Perrillo, Jonna. 2012. Uncivil Rights: Teachers, Unions, and Race in the Battle for School Equity . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rasmussen, Birgit Brander. 2010. “‘Attended with Great Inconveniences’: Slave Literacy and the 1740 South Carolina Negro Act.” PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 125 (1): 201–3. https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2010.125.1.201 .

- Rose, Deondra. 2022. “Race, Post-Reconstruction Politics, and the Birth of Federal Support for Black Colleges.” Journal of Policy History 34 (1): 25–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030621000270 .

- Scribner, Campbell F. 2020. “Surveying the Destruction of African American Schoolhouses in the South, 1864–1876.” Journal of the Civil War Era 10 (4): 469–94.

- Span, Christopher M. 2015. “Post-Slavery? Post-Segregation? Post-Racial? A History of the Impact of Slavery, Segregation, and Racism on the Education of African Americans.” Teachers College Record 117 (14): 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811511701404 .

- Wasserman, Marni. 2014. Prudence Crandall’s Legacy: The Fight for Equality in the 1830s, Dred Scott, and Brown V. Board of Education . Driftless Connecticut Series Books. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.

- Watkins, William H. 2001. The White Architects of Black Education: Ideology and Power in America, 1865-1954 . Teaching for Social Justice Series. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Williams, Heather Andrea. 2005. Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom . 1st ed. The John Hope Franklin Series in African American History and Culture Ser. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Citations for Images

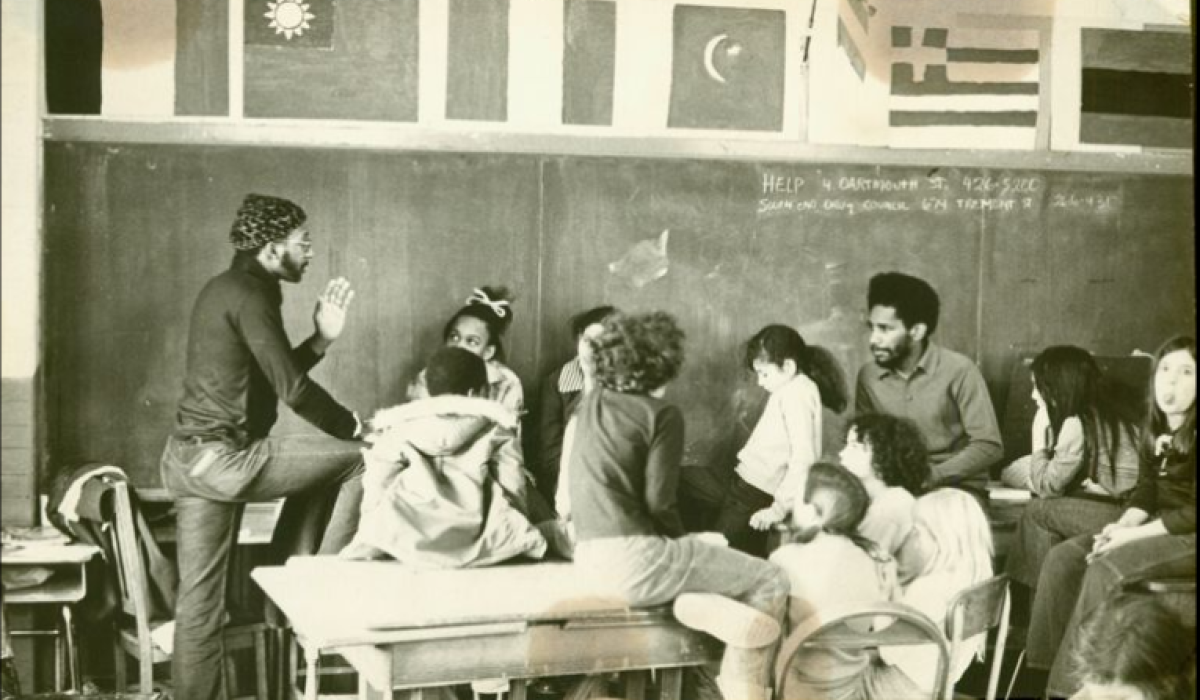

- Students and teachers in a Boston public school classroom, circa 1973 | Unidentified artist. Part of Ruth Batson Papers, 1919-2003. Folder: #2.10. Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute MC590-2.11-25. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvwork491021/catalog

- African-American school children playing outdoors, 1932-1933 | Unidentified artist. Part of Ethel Sturges Dummer Papers. Folder: "Professional" papers of ESD by topic: Education: Chicago Schools: Joint Committee on Education - composed of representatives of number of Chicago women's clubs "formed to arouse an intelligent interest in our public schools": Chicago Woman's Club: Miscellaneous material relating to Chicago schools. Educational organizations and schools outside of Chicago. RLG collection level record MHVW85-A165. Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute MC590-2.11-25. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/via/olvgroup1004968/catalog

- Group portrait of Sedalia Public School’s graduating class of 1938-1939, circa 1938-1939 | Unidentified artist. Group portrait, outside, of graduating class, Sedalia Public School. Part of Charlotte Hawkins Brown Papers. Folder: Photographs: Students, events, buildings, n.d. Sedalia Public School, 1938-39, n.d. HOLLIS collection level record 000605309 . RLG collection level record MHVW85-A64. Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute A146-69-9. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/via/olvwork20013567/catalog

IMAGES