Purdue Online Writing Lab College of Liberal Arts

Tables and Figures

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Note: This page reflects the latest version of the APA Publication Manual (i.e., APA 7), which released in October 2019. The equivalent resources for the older APA 6 style can be found at this page as well as at this page (our old resources covered the material on this page on two separate pages).

The purpose of tables and figures in documents is to enhance your readers' understanding of the information in the document; usually, large amounts of information can be communicated more efficiently in tables or figures. Tables are any graphic that uses a row and column structure to organize information, whereas figures include any illustration or image other than a table.

General guidelines

Visual material such as tables and figures can be used quickly and efficiently to present a large amount of information to an audience, but visuals must be used to assist communication, not to use up space, or disguise marginally significant results behind a screen of complicated statistics. Ask yourself this question first: Is the table or figure necessary? For example, it is better to present simple descriptive statistics in the text, not in a table.

Relation of Tables or Figures and Text

Because tables and figures supplement the text, refer in the text to all tables and figures used and explain what the reader should look for when using the table or figure. Focus only on the important point the reader should draw from them, and leave the details for the reader to examine on their own.

Documentation

If you are using figures, tables and/or data from other sources, be sure to gather all the information you will need to properly document your sources.

Integrity and Independence

Each table and figure must be intelligible without reference to the text, so be sure to include an explanation of every abbreviation (except the standard statistical symbols and abbreviations).

Organization, Consistency, and Coherence

Number all tables sequentially as you refer to them in the text (Table 1, Table 2, etc.), likewise for figures (Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.). Abbreviations, terminology, and probability level values must be consistent across tables and figures in the same article. Likewise, formats, titles, and headings must be consistent. Do not repeat the same data in different tables.

Data in a table that would require only two or fewer columns and rows should be presented in the text. More complex data is better presented in tabular format. In order for quantitative data to be presented clearly and efficiently, it must be arranged logically, e.g. data to be compared must be presented next to one another (before/after, young/old, male/female, etc.), and statistical information (means, standard deviations, N values) must be presented in separate parts of the table. If possible, use canonical forms (such as ANOVA, regression, or correlation) to communicate your data effectively.

A generic example of a table with multiple notes formatted in APA 7 style.

Elements of Tables

Number all tables with Arabic numerals sequentially. Do not use suffix letters (e.g. Table 3a, 3b, 3c); instead, combine the related tables. If the manuscript includes an appendix with tables, identify them with capital letters and Arabic numerals (e.g. Table A1, Table B2).

Like the title of the paper itself, each table must have a clear and concise title. Titles should be written in italicized title case below the table number, with a blank line between the number and the title. When appropriate, you may use the title to explain an abbreviation parenthetically.

Comparison of Median Income of Adopted Children (AC) v. Foster Children (FC)

Keep headings clear and brief. The heading should not be much wider than the widest entry in the column. Use of standard abbreviations can aid in achieving that goal. There are several types of headings:

- Stub headings describe the lefthand column, or stub column , which usually lists major independent variables.

- Column headings describe entries below them, applying to just one column.

- Column spanners are headings that describe entries below them, applying to two or more columns which each have their own column heading. Column spanners are often stacked on top of column headings and together are called decked heads .

- Table Spanners cover the entire width of the table, allowing for more divisions or combining tables with identical column headings. They are the only type of heading that may be plural.

All columns must have headings, written in sentence case and using singular language (Item rather than Items) unless referring to a group (Men, Women). Each column’s items should be parallel (i.e., every item in a column labeled “%” should be a percentage and does not require the % symbol, since it’s already indicated in the heading). Subsections within the stub column can be shown by indenting headings rather than creating new columns:

Chemical Bonds

Ionic

Covalent

Metallic

The body is the main part of the table, which includes all the reported information organized in cells (intersections of rows and columns). Entries should be center aligned unless left aligning them would make them easier to read (longer entries, usually). Word entries in the body should use sentence case. Leave cells blank if the element is not applicable or if data were not obtained; use a dash in cells and a general note if it is necessary to explain why cells are blank. In reporting the data, consistency is key: Numerals should be expressed to a consistent number of decimal places that is determined by the precision of measurement. Never change the unit of measurement or the number of decimal places in the same column.

There are three types of notes for tables: general, specific, and probability notes. All of them must be placed below the table in that order.

General notes explain, qualify or provide information about the table as a whole. Put explanations of abbreviations, symbols, etc. here.

Example: Note . The racial categories used by the US Census (African-American, Asian American, Latinos/-as, Native-American, and Pacific Islander) have been collapsed into the category “non-White.” E = excludes respondents who self-identified as “White” and at least one other “non-White” race.

Specific notes explain, qualify or provide information about a particular column, row, or individual entry. To indicate specific notes, use superscript lowercase letters (e.g. a , b , c ), and order the superscripts from left to right, top to bottom. Each table’s first footnote must be the superscript a .

a n = 823. b One participant in this group was diagnosed with schizophrenia during the survey.

Probability notes provide the reader with the results of the tests for statistical significance. Asterisks indicate the values for which the null hypothesis is rejected, with the probability ( p value) specified in the probability note. Such notes are required only when relevant to the data in the table. Consistently use the same number of asterisks for a given alpha level throughout your paper.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

If you need to distinguish between two-tailed and one-tailed tests in the same table, use asterisks for two-tailed p values and an alternate symbol (such as daggers) for one-tailed p values.

* p < .05, two-tailed. ** p < .01, two-tailed. † p <.05, one-tailed. †† p < .01, one-tailed.

Borders

Tables should only include borders and lines that are needed for clarity (i.e., between elements of a decked head, above column spanners, separating total rows, etc.). Do not use vertical borders, and do not use borders around each cell. Spacing and strict alignment is typically enough to clarify relationships between elements.

Example of a table in the text of an APA 7 paper. Note the lack of vertical borders.

Tables from Other Sources

If using tables from an external source, copy the structure of the original exactly, and cite the source in accordance with APA style .

Table Checklist

(Taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th ed., Section 7.20)

- Is the table necessary?

- Does it belong in the print and electronic versions of the article, or can it go in an online supplemental file?

- Are all comparable tables presented consistently?

- Are all tables numbered with Arabic numerals in the order they are mentioned in the text? Is the table number bold and left-aligned?

- Are all tables referred to in the text?

- Is the title brief but explanatory? Is it presented in italicized title case and left-aligned?

- Does every column have a column heading? Are column headings centered?

- Are all abbreviations; special use of italics, parentheses, and dashes; and special symbols explained?

- Are the notes organized according to the convention of general, specific, probability?

- Are table borders correctly used (top and bottom of table, beneath column headings, above table spanners)?

- Does the table use correct line spacing (double for the table number, title, and notes; single, one and a half, or double for the body)?

- Are entries in the left column left-aligned beneath the centered stub heading? Are all other column headings and cell entries centered?

- Are confidence intervals reported for all major point estimates?

- Are all probability level values correctly identified, and are asterisks attached to the appropriate table entries? Is a probability level assigned the same number of asterisks in all the tables in the same document?

- If the table or its data are from another source, is the source properly cited? Is permission necessary to reproduce the table?

Figures include all graphical displays of information that are not tables. Common types include graphs, charts, drawings, maps, plots, and photos. Just like tables, figures should supplement the text and should be both understandable on their own and referenced fully in the text. This section details elements of formatting writers must use when including a figure in an APA document, gives an example of a figure formatted in APA style, and includes a checklist for formatting figures.

Preparing Figures

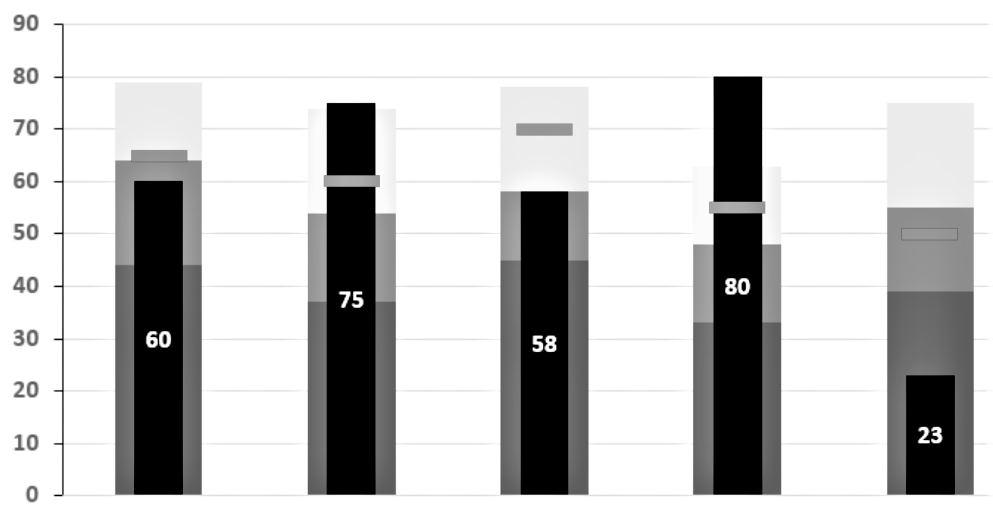

In preparing figures, communication and readability must be the ultimate criteria. Avoid the temptation to use the special effects available in most advanced software packages. While three-dimensional effects, shading, and layered text may look interesting to the author, overuse, inconsistent use, and misuse may distort the data, and distract or even annoy readers. Design properly done is inconspicuous, almost invisible, because it supports communication. Design improperly, or amateurishly, done draws the reader’s attention from the data, and makes him or her question the author’s credibility. Line drawings are usually a good option for readability and simplicity; for photographs, high contrast between background and focal point is important, as well as cropping out extraneous detail to help the reader focus on the important aspects of the photo.

Parts of a Figure

All figures that are part of the main text require a number using Arabic numerals (Figure 1, Figure 2, etc.). Numbers are assigned based on the order in which figures appear in the text and are bolded and left aligned.

Under the number, write the title of the figure in italicized title case. The title should be brief, clear, and explanatory, and both the title and number should be double spaced.

The image of the figure is the body, and it is positioned underneath the number and title. The image should be legible in both size and resolution; fonts should be sans serif, consistently sized, and between 8-14 pt. Title case should be used for axis labels and other headings; descriptions within figures should be in sentence case. Shading and color should be limited for clarity; use patterns along with color and check contrast between colors with free online checkers to ensure all users (people with color vision deficiencies or readers printing in grayscale, for instance) can access the content. Gridlines and 3-D effects should be avoided unless they are necessary for clarity or essential content information.

Legends, or keys, explain symbols, styles, patterns, shading, or colors in the image. Words in the legend should be in title case; legends should go within or underneath the image rather than to the side. Not all figures will require a legend.

Notes clarify the content of the figure; like tables, notes can be general, specific, or probability. General notes explain units of measurement, symbols, and abbreviations, or provide citation information. Specific notes identify specific elements using superscripts; probability notes explain statistical significance of certain values.

A generic example of a figure formatted in APA 7 style.

Figure Checklist

(Taken from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7 th ed., Section 7.35)

- Is the figure necessary?

- Does the figure belong in the print and electronic versions of the article, or is it supplemental?

- Is the figure simple, clean, and free of extraneous detail?

- Is the figure title descriptive of the content of the figure? Is it written in italic title case and left aligned?

- Are all elements of the figure clearly labeled?

- Are the magnitude, scale, and direction of grid elements clearly labeled?

- Are parallel figures or equally important figures prepared according to the same scale?

- Are the figures numbered consecutively with Arabic numerals? Is the figure number bold and left aligned?

- Has the figure been formatted properly? Is the font sans serif in the image portion of the figure and between sizes 8 and 14?

- Are all abbreviations and special symbols explained?

- If the figure has a legend, does it appear within or below the image? Are the legend’s words written in title case?

- Are the figure notes in general, specific, and probability order? Are they double-spaced, left aligned, and in the same font as the paper?

- Are all figures mentioned in the text?

- Has written permission for print and electronic reuse been obtained? Is proper credit given in the figure caption?

- Have all substantive modifications to photographic images been disclosed?

- Are the figures being submitted in a file format acceptable to the publisher?

- Have the files been produced at a sufficiently high resolution to allow for accurate reproduction?

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Use Tables & Graphs in a Research Paper

It might not seem very relevant to the story and outcome of your study, but how you visually present your experimental or statistical results can play an important role during the review and publication process of your article. A presentation that is in line with the overall logical flow of your story helps you guide the reader effectively from your introduction to your conclusion.

If your results (and the way you organize and present them) don’t follow the story you outlined in the beginning, then you might confuse the reader and they might end up doubting the validity of your research, which can increase the chance of your manuscript being rejected at an early stage. This article illustrates the options you have when organizing and writing your results and will help you make the best choice for presenting your study data in a research paper.

Why does data visualization matter?

Your data and the results of your analysis are the core of your study. Of course, you need to put your findings and what you think your findings mean into words in the text of your article. But you also need to present the same information visually, in the results section of your manuscript, so that the reader can follow and verify that they agree with your observations and conclusions.

The way you visualize your data can either help the reader to comprehend quickly and identify the patterns you describe and the predictions you make, or it can leave them wondering what you are trying to say or whether your claims are supported by evidence. Different types of data therefore need to be presented in different ways, and whatever way you choose needs to be in line with your story.

Another thing to keep in mind is that many journals have specific rules or limitations (e.g., how many tables and graphs you are allowed to include, what kind of data needs to go on what kind of graph) and specific instructions on how to generate and format data tables and graphs (e.g., maximum number of subpanels, length and detail level of tables). In the following, we will go into the main points that you need to consider when organizing your data and writing your result section .

Table of Contents:

Types of data , when to use data tables .

- When to Use Data Graphs

Common Types of Graphs in Research Papers

Journal guidelines: what to consider before submission.

Depending on the aim of your research and the methods and procedures you use, your data can be quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative data, whether objective (e.g., size measurements) or subjective (e.g., rating one’s own happiness on a scale), is what is usually collected in experimental research. Quantitative data are expressed in numbers and analyzed with the most common statistical methods. Qualitative data, on the other hand, can consist of case studies or historical documents, or it can be collected through surveys and interviews. Qualitative data are expressed in words and needs to be categorized and interpreted to yield meaningful outcomes.

Quantitative data example: Height differences between two groups of participants Qualitative data example: Subjective feedback on the food quality in the work cafeteria

Depending on what kind of data you have collected and what story you want to tell with it, you have to find the best way of organizing and visualizing your results.

When you want to show the reader in detail how your independent and dependent variables interact, then a table (with data arranged in columns and rows) is your best choice. In a table, readers can look up exact values, compare those values between pairs or groups of related measurements (e.g., growth rates or outcomes of a medical procedure over several years), look at ranges and intervals, and select specific factors to search for patterns.

Tables are not restrained to a specific type of data or measurement. Since tables really need to be read, they activate the verbal system. This requires focus and some time (depending on how much data you are presenting), but it gives the reader the freedom to explore the data according to their own interest. Depending on your audience, this might be exactly what your readers want. If you explain and discuss all the variables that your table lists in detail in your manuscript text, then you definitely need to give the reader the chance to look at the details for themselves and follow your arguments. If your analysis only consists of simple t-tests to assess differences between two groups, you can report these results in the text (in this case: mean, standard deviation, t-statistic, and p-value), and do not necessarily need to include a table that simply states the same numbers again. If you did extensive analyses but focus on only part of that data (and clearly explain why, so that the reader does not think you forgot to talk about the rest), then a graph that illustrates and emphasizes the specific result or relationship that you consider the main point of your story might be a better choice.

When to Use Data Graphs

Graphs are a visual display of information and show the overall shape of your results rather than the details. If used correctly, a visual representation helps your (or your reader’s) brain to quickly understand large amounts of data and spot patterns, trends, and exceptions or outliers. Graphs also make it easier to illustrate relationships between entire data sets. This is why, when you analyze your results, you usually don’t just look at the numbers and the statistical values of your tests, but also at histograms, box plots, and distribution plots, to quickly get an overview of what is going on in your data.

Line graphs

When you want to illustrate a change over a continuous range or time, a line graph is your best choice. Changes in different groups or samples over the same range or time can be shown by lines of different colors or with different symbols.

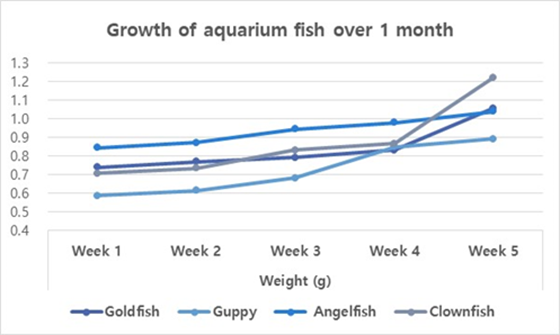

Example: Let’s collapse across the different food types and look at the growth of our four fish species over time.

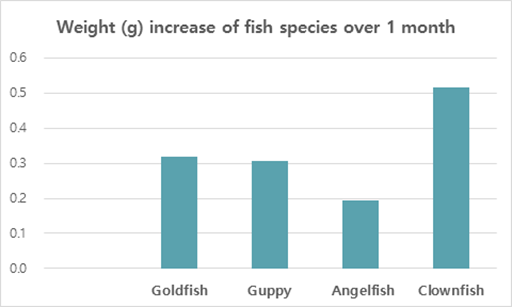

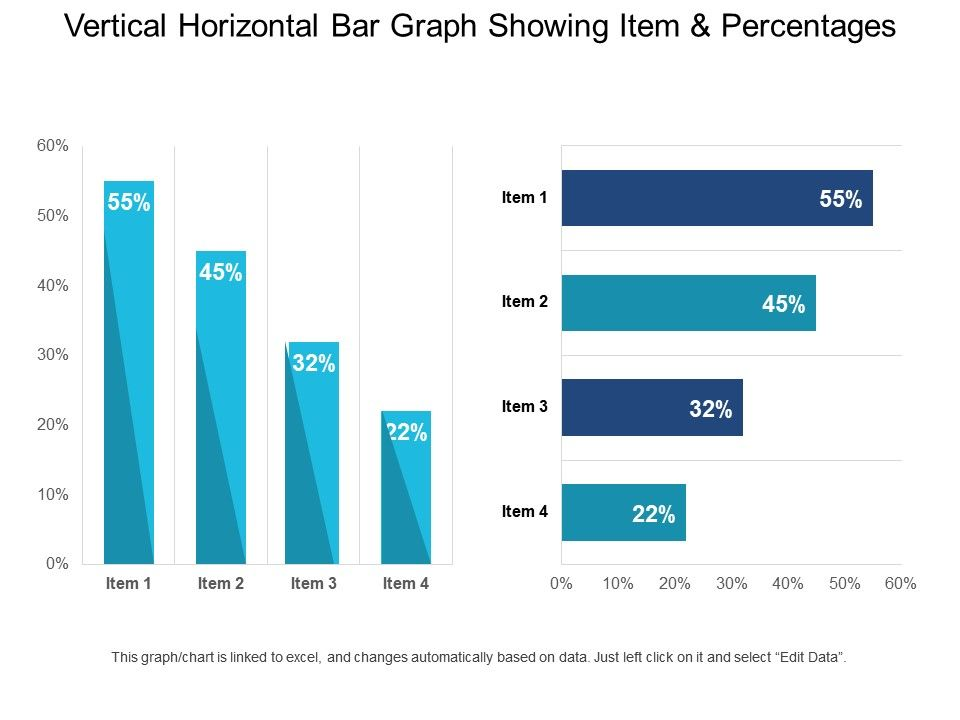

You should use a bar graph when your data is not continuous but divided into categories that are not necessarily connected, such as different samples, methods, or setups. In our example, the different fish types or the different types of food are such non-continuous categories.

Example: Let’s collapse across the food types again and also across time, and only compare the overall weight increase of our four fish types at the end of the feeding period.

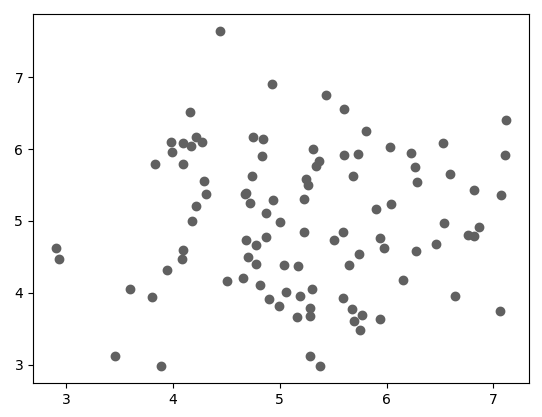

Scatter plots

Scatter plots can be used to illustrate the relationship between two variables — but note that both have to be continuous. The following example displays “fish length” as an additional variable–none of the variables in our table above (fish type, fish food, time) are continuous, and they can therefore not be used for this kind of graph.

As you see, these example graphs all contain less data than the table above, but they lead the reader to exactly the key point of your results or the finding you want to emphasize. If you let your readers search for these observations in a big table full of details that are not necessarily relevant to the claims you want to make, you can create unnecessary confusion. Most journals allow you to provide bigger datasets as supplementary information, and some even require you to upload all your raw data at submission. When you write up your manuscript, however, matching the data presentation to the storyline is more important than throwing everything you have at the reader.

Don’t forget that every graph needs to have clear x and y axis labels , a title that summarizes what is shown above the figure, and a descriptive legend/caption below. Since your caption needs to stand alone and the reader needs to be able to understand it without looking at the text, you need to explain what you measured/tested and spell out all labels and abbreviations you use in any of your graphs once more in the caption (even if you think the reader “should” remember everything by now, make it easy for them and guide them through your results once more). Have a look at this article if you need help on how to write strong and effective figure legends .

Even if you have thought about the data you have, the story you want to tell, and how to guide the reader most effectively through your results, you need to check whether the journal you plan to submit to has specific guidelines and limitations when it comes to tables and graphs. Some journals allow you to submit any tables and graphs initially (as long as tables are editable (for example in Word format, not an image) and graphs of high enough resolution.

Some others, however, have very specific instructions even at the submission stage, and almost all journals will ask you to follow their formatting guidelines once your manuscript is accepted. The closer your figures are already to those guidelines, the faster your article can be published. This PLOS One Figure Preparation Checklist is a good example of how extensive these instructions can be – don’t wait until the last minute to realize that you have to completely reorganize your results because your target journal does not accept tables above a certain length or graphs with more than 4 panels per figure.

Some things you should always pay attention to (and look at already published articles in the same journal if you are unsure or if the author instructions seem confusing) are the following:

- How many tables and graphs are you allowed to include?

- What file formats are you allowed to submit?

- Are there specific rules on resolution/dimension/file size?

- Should your figure files be uploaded separately or placed into the text?

- If figures are uploaded separately, do the files have to be named in a specific way?

- Are there rules on what fonts to use or to avoid and how to label subpanels?

- Are you allowed to use color? If not, make sure your data sets are distinguishable.

If you are dealing with digital image data, then it might also be a good idea to familiarize yourself with the difference between “adjusting” for clarity and visibility and image manipulation, which constitutes scientific misconduct . And to fully prepare your research paper for publication before submitting it, be sure to receive proofreading services , including journal manuscript editing and research paper editing , from Wordvice’s professional academic editors .

Best Practices of Graphs and Charts in Research Papers

Do you want to know how to make your research papers stand out through charts and graphs? Then this blog is what you need. Read it now!

We live in a world of data! From simple to complicated and scattered to neatly arranged based on several factors – we are entirely encapsulated in it.

Furthermore, at some point or another, we have all used a graph to represent this aforementioned data in the form of a comparison, a trend, or just a division of the whole (like a pie).

Let’s be honest – what a graph is, what are its advantages, and what are its disadvantages have been discussed at length by numerous people, around the globe, over the past decades.

Yet, it retains its gravity with the increasing number of settings it can be used in, so much so that a free infographic maker can be used to provide you the most beautiful infographics in half the time.

So before we dive into the specifics of their usage in Research Papers, let’s take a quick recap, shall we?

What is a graph?

A graph, in layman terms, is a pictorial representation of organized data that helps the readers of the same understand complex information more easily.

While each kind of visual aid comes with its own pros and cons, some of the main features that underlie each can be summed up as below:

- They provide information in the form of easy-to-understand images.

- Different data types require different graphs.

- They are often unable to display the major assumptions and causes behind the data fluctuations.

- They are easier to manipulate than factual information.

When do you need a chart or graph in the research paper?

A research paper is in itself a resultant report of all the investigations and surveys you conducted, be it through primary or secondary data. However, not everyone can understand those figures or calculations and at times the reader might have to read the entire copy just to get to the numbers.

This calls for a simpler approach to ease the process. You may end up using a chart for any one or multiple reasons mentioned next.

To prove your point

It is far easier to attest to your standing when you have a graphical representation alongside the tabulated results. Your reader might be much more comfortable when they don’t have to try and understand the calculations just to realize what your final conclusion is.

To make your information more comprehensive

The level of your audience’s comprehension can be directly related to the ease with which they can make sense of the compiled data. Using a chart can help enhance this ease further.

A graph can describe more information with minimum real estate

Conveying more details in the least amount of words and space is an art that can be practiced with the help of graphs. A diagram that pictorially represents the entire data collection and its output is also more visually appealing.

Deliver complicated points

With illustrations and grids, you can put across the complex data in a simplified version which drives your point home while being easier on the reader’s eyes.

Compare data

When you are looking to compare two or more sets of data consisting of a whole lot of factors and numbers, it is a good idea to use visual aids like a chart that can help the reader understand the comparative state of each element at a glance.

Assess If You Actually Need a Graph/ Chart

Oftentimes, students and researchers alike tend to use graphs more than needed in their papers to make their point stand out prominently.

However, there are cases where you can simply put across your premise as well as results in just a few sentences.

In such scenarios, it is advisable to avoid the usage of charts as they can lower the authority of your more important diagrams further in the research.

Select the Right Graph for the Message

As mentioned earlier, different types of data require different kinds of charts. On one hand, pie charts could be ascertained as perfect for displaying an approximate division of hours of a day and the way they are spent but on the other, a line graph would be more suitable to show a market trend spread over a few months or years.

A wrong graph chosen to plot your data might just make it more difficult for the user to make sense of the research rather than simplifying it and that is the absolute last thing you’d want. Using a graph creator online can be a way to go to avoid the same.

Therefore, your understanding of the variety of these diagrams is equally important. Broadly, they can be categorized into the following.

Types of graphs and charts

- Scatter Plot

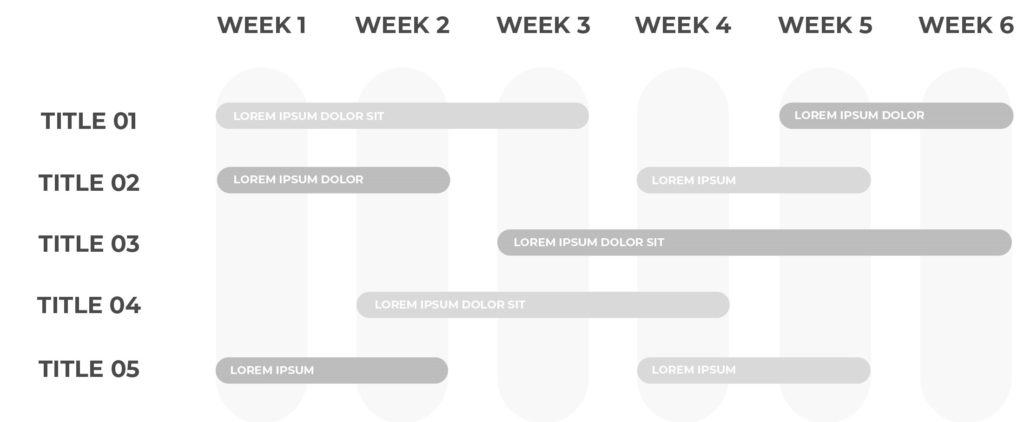

- Gantt Chart

- Bullet Chart

For understanding these and much more, you can go through other articles in our blog like: Ultimate Guide on Creating Comprehensive Graphs for Your Research Paper .

Focus on Readability

The most important function of a chart is to bring to the forefront the crux of a topic, that can be understood by anyone reading it, even without a firm grasp of the subject at hand. Having said that, we would like to strongly emphasize the need for a legible diagram.

If your reader cannot decipher the diagrams you’ve used, its presence is as good as none. Per our observation, several students, researchers, and even scientists make this error of integrating so much data in one graph that it becomes unintelligible.

An incomprehensible illustration is viewed by most as nothing more than an image, thus hampering the reading experience of your report.

To ensure your chart is readable, formatting it optimally is a crucial step. It includes not just the font type, font size, and symbols used therein but also elements like the colors used, caption & title given to the graph, names used for each axis as well as an index or data field for reference. Some useful considerations regarding readability:

- The text used on a diagram should always be kept to a minimum while making sure the message is not being lost.

- Symbols used should be distinct so as to avoid confusion.

- De-clutter the figure by removing all non-essential data and elements from the grid and adding it to the footnote instead.

- The background of the chart should be in good contrast to the chart itself, to make certain that the data stands out prominently.

- The axes should not be named simply “temperature” & “time” for instance unless it provides a complete clarification of the segments.

- Choose the graph’s layout to maximize readability.

Maintain the Look-and-Feel

A chart’s visual appeal is just as important as the data it is representing, if not more. An attractive diagram compels the reader to stop and go through the information it is rendering instead of glimpsing it once and moving ahead.

You can ensure this step by simply keeping in mind the following tips.

Informative Title

The heading you give to your graph is of significant importance because it lets the reader know what is it that the picture is portraying. It should be self-explanatory and clear because based on that the user will be making a decision to read or not read the chart.

Acknowledge the Source

Adding a small footnote recognizing and pointing to the source of the information being displayed lends credibility and authority to your data.

Brand Integration

If you are doing the research under a specific college, university or company, remember to use their mandatory colors and logos.

Accurate Dimensions

Give the first preference to a 2D chart as it is simpler to understand. Nevertheless, if you find yourself in a position to use a 3D graph, see to it that the same is comprehensible and includes only the truly important elements on the grid.

Do not, under any circumstances, forget to add a relevant key to the diagram that gives clarity to the presented data.

Keep all The Junk and Fluff Aside

As we mentioned above, a clean chart is the need of the hour.

Clearing up your figures of all the unnecessary elements helps the most important information stand out, giving the reader exactly what he/ she came for.

- Use the minimum amount of text on your chart. You can add any notes you wish to in the footnote of the same.

- Use short forms and abbreviations wherever possible.

- Avoid using too many colors or the graph might become too loud and noisy for the reader.

Avoid Using 3D Graphs

If at all feasible, we would highly recommend you avoid the use of 3D Graphs. While at a glance they may make an attractive picture, but in actuality, they can often be misleading.

A three-dimensional chart, be it in the form of a pie chart or a bar graph can be difficult to interpret due to the differences in perspectives. When viewed from different angles, the figure could point to different results due to a distorted visual relationship. This also affects the information being derived from it.

Moreover, 3D spacing makes a comparison between the values and volumes of each factor challenging.

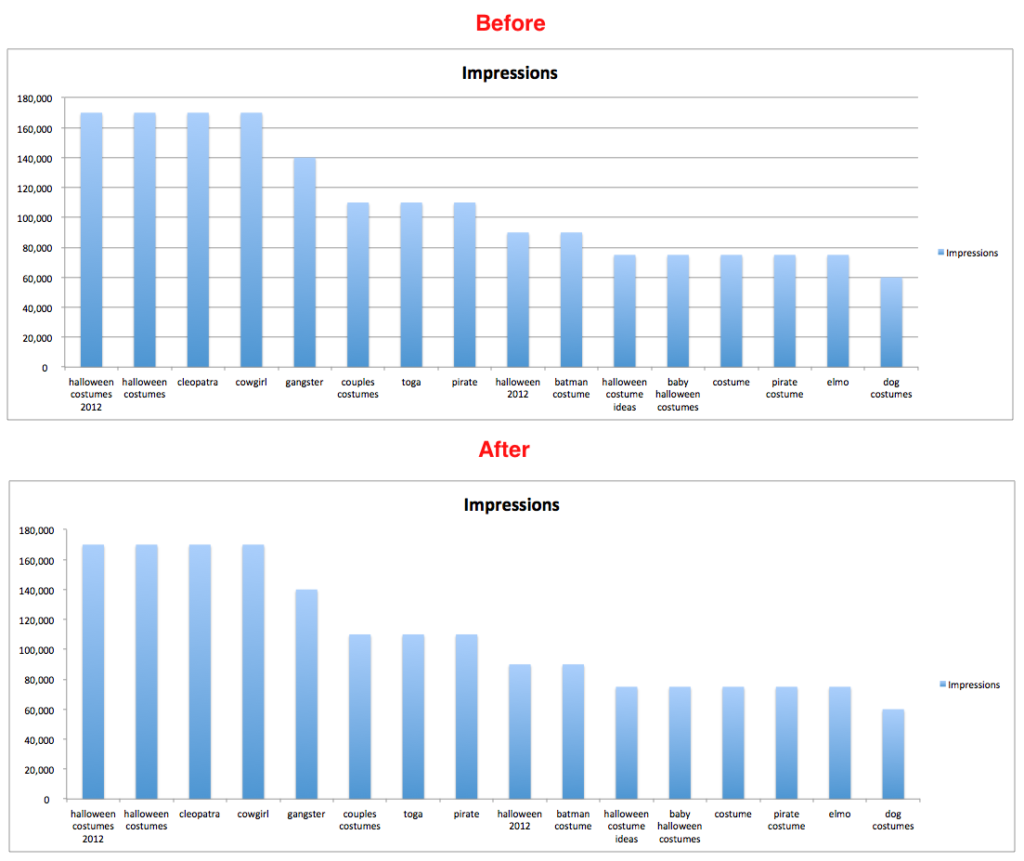

Make Graphs with No Grid Lines

Illustrated above under our ‘Focus On Readability’ section, you can find the perfect example of why using grid lines can sometimes be a bad idea.

Remember, if the reader is looking for incremental differences with exact data points, they can always refer to your tabulated facts and figures.

However, what they are indeed looking for in the graph is a general trend. Thus eliminating the grid lines might actually be a good proposition.

Our Brain Focuses on What Stands Out

While designing an infographic, be it in Excel or in a specialized tool like Mind the Graph , one of the most essential things to keep in mind is that you have a lot of data and not all of it is as highly significant.

Always ensure that you are highlighting the important parts in a way that they are vividly noticeable and attract attention.

You would not want your readers to miss out on those bits in a sea of data and the only way to make certain that they don’t is by creating the graph accordingly.

People Comprehend Visually Elegant Data

Take a quick look at the picture below.

I’m certain that while spotting the animals in the first two images would have been simple, it would have taken a little more effort for your brain to process its presence in the third one.

This happened because where in the first two, contrasting colors were used for the animal and the trees behind, there was no such differentiation in the last picture.

This is to illustrate our simple point that your mind, just like your reader’s, is programmed to comprehend information that is visually refined. Therefore, using colors that aren’t too loud and similar is the right choice to make.

Get a Reality Check

After going through the above tips, we are sure you’re going to be able to take your graphs’ quality a notch higher. But if you’re still apprehensive, we recommend getting a reality check.

Take an Opinion

Have your best friend, your project guide, or anyone you trust and hold in esteem go through your infographics. Just remember to choose a person who would be giving you the best and unbiased advice.

Gather Feedbacks

Ask the aforementioned people to give you honest feedback about your graphs along with suggestions to make them better.

Depending on the responses you’ve received, get down to editing the charts to make them more comprehensive and readable.

Research papers are some of the most important documents you write and publish in your entire life and good statistical and scientific visualizations are the key to making them that much better.

Your charts will always be dependent on the kind of data you wish to represent, but these tips are going to help you across all domains. Here’s a recap of everything we went through in this article:

So what are you waiting for?

Bring out that data you’ve compiled and get down to creating some of the most beautiful graphs seen.

- Image Source.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

About Fabricio Pamplona

Fabricio Pamplona is the founder of Mind the Graph - a tool used by over 400K users in 60 countries. He has a Ph.D. and solid scientific background in Psychopharmacology and experience as a Guest Researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry (Germany) and Researcher in D'Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR, Brazil). Fabricio holds over 2500 citations in Google Scholar. He has 10 years of experience in small innovative businesses, with relevant experience in product design and innovation management. Connect with him on LinkedIn - Fabricio Pamplona .

Content tags

Chapter 12: Descriptive Statistics

12.3 expressing your results, learning objectives.

- Write out simple descriptive statistics in American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Interpret and create simple APA-style graphs—including bar graphs, line graphs, and scatterplots.

- Interpret and create simple APA-style tables—including tables of group or condition means and correlation matrixes.

Once you have conducted your descriptive statistical analyses, you will need to present them to others. In this section, we focus on presenting descriptive statistical results in writing, in graphs, and in tables—following American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines for written research reports. These principles can be adapted easily to other presentation formats such as posters and slide show presentations.

Presenting Descriptive Statistics in Writing

When you have a small number of results to report, it is often most efficient to write them out. There are a few important APA style guidelines here. First, statistical results are always presented in the form of numerals rather than words and are usually rounded to two decimal places (e.g., “2.00” rather than “two” or “2”). They can be presented either in the narrative description of the results or parenthetically—much like reference citations. Here are some examples:

The mean age of the participants was 22.43 years with a standard deviation of 2.34. Among the low self-esteem participants, those in a negative mood expressed stronger intentions to have unprotected sex ( M = 4.05, SD = 2.32) than those in a positive mood ( M = 2.15, SD = 2.27). The treatment group had a mean of 23.40 ( SD = 9.33), while the control group had a mean of 20.87 ( SD = 8.45). The test-retest correlation was .96. There was a moderate negative correlation between the alphabetical position of respondents’ last names and their response time ( r = −.27).

Notice that when presented in the narrative, the terms mean and standard deviation are written out, but when presented parenthetically, the symbols M and SD are used instead. Notice also that it is especially important to use parallel construction to express similar or comparable results in similar ways. The third example is much better than the following nonparallel alternative:

Presenting Descriptive Statistics in Graphs

When you have a large number of results to report, you can often do it more clearly and efficiently with a graph. When you prepare graphs for an APA-style research report, there are some general guidelines that you should keep in mind. First, the graph should always add important information rather than repeat information that already appears in the text or in a table. (If a graph presents information more clearly or efficiently, then you should keep the graph and eliminate the text or table.) Second, graphs should be as simple as possible. For example, the Publication Manual discourages the use of color unless it is absolutely necessary (although color can still be an effective element in posters, slide show presentations, or textbooks.) Third, graphs should be interpretable on their own. A reader should be able to understand the basic result based only on the graph and its caption and should not have to refer to the text for an explanation.

There are also several more technical guidelines for graphs that include the following:

- The graph should be slightly wider than it is tall.

- The independent variable should be plotted on the x- axis and the dependent variable on the y- axis.

- Values should increase from left to right on the x- axis and from bottom to top on the y- axis.

Axis Labels and Legends

- Axis labels should be clear and concise and include the units of measurement if they do not appear in the caption.

- Axis labels should be parallel to the axis.

- Legends should appear within the boundaries of the graph.

- Text should be in the same simple font throughout and differ by no more than four points.

- Captions should briefly describe the figure, explain any abbreviations, and include the units of measurement if they do not appear in the axis labels.

- Captions in an APA manuscript should be typed on a separate page that appears at the end of the manuscript. See Chapter 11 “Presenting Your Research” for more information.

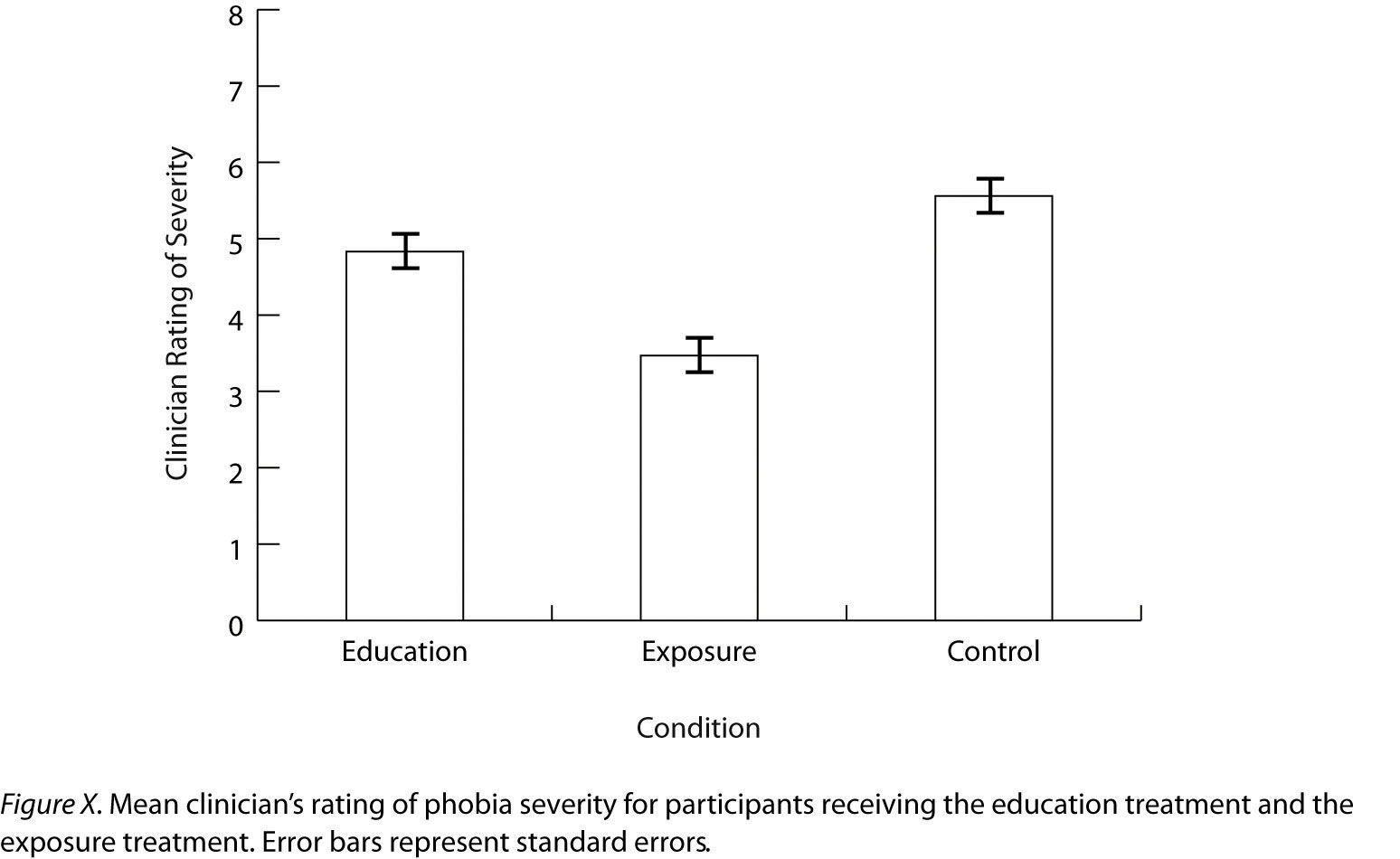

As we have seen throughout this book, bar graphs are generally used to present and compare the mean scores for two or more groups or conditions. The bar graph in Figure 12.12 “Sample APA-Style Bar Graph, With Error Bars Representing the Standard Errors, Based on Research by Ollendick and Colleagues” is an APA-style version of Figure 12.5 “Bar Graph Showing Mean Clinician Phobia Ratings for Children in Two Treatment Conditions” . Notice that it conforms to all the guidelines listed. A new element in Figure 12.12 “Sample APA-Style Bar Graph, With Error Bars Representing the Standard Errors, Based on Research by Ollendick and Colleagues” is the smaller vertical bars that extend both upward and downward from the top of each main bar. These are error bars , and they represent the variability in each group or condition. Although they sometimes extend one standard deviation in each direction, they are more likely to extend one standard error in each direction (as in Figure 12.12 “Sample APA-Style Bar Graph, With Error Bars Representing the Standard Errors, Based on Research by Ollendick and Colleagues” ). The standard error is the standard deviation of the group divided by the square root of the sample size of the group. The standard error is used because, in general, a difference between group means that is greater than two standard errors is statistically significant. Thus one can “see” whether a difference is statistically significant based on a bar graph with error bars.

Figure 12.12 Sample APA-Style Bar Graph, With Error Bars Representing the Standard Errors, Based on Research by Ollendick and Colleagues

Line Graphs

Line graphs are used to present correlations between quantitative variables when the independent variable has, or is organized into, a relatively small number of distinct levels. Each point in a line graph represents the mean score on the dependent variable for participants at one level of the independent variable. Figure 12.13 “Sample APA-Style Line Graph Based on Research by Carlson and Conard” is an APA-style version of the results of Carlson and Conard. Notice that it includes error bars representing the standard error and conforms to all the stated guidelines.

Figure 12.13 Sample APA-Style Line Graph Based on Research by Carlson and Conard

In most cases, the information in a line graph could just as easily be presented in a bar graph. In Figure 12.13 “Sample APA-Style Line Graph Based on Research by Carlson and Conard” , for example, one could replace each point with a bar that reaches up to the same level and leave the error bars right where they are. This emphasizes the fundamental similarity of the two types of statistical relationship. Both are differences in the average score on one variable across levels of another. The convention followed by most researchers, however, is to use a bar graph when the variable plotted on the x- axis is categorical and a line graph when it is quantitative.

Scatterplots

Scatterplots are used to present relationships between quantitative variables when the variable on the x- axis (typically the independent variable) has a large number of levels. Each point in a scatterplot represents an individual rather than the mean for a group of individuals, and there are no lines connecting the points. The graph in Figure 12.14 “Sample APA-Style Scatterplot” is an APA-style version of Figure 12.8 “Statistical Relationship Between Several College Students’ Scores on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale Given on Two Occasions a Week Apart” , which illustrates a few additional points. First, when the variables on the x- axis and y -axis are conceptually similar and measured on the same scale—as here, where they are measures of the same variable on two different occasions—this can be emphasized by making the axes the same length. Second, when two or more individuals fall at exactly the same point on the graph, one way this can be indicated is by offsetting the points slightly along the x- axis. Other ways are by displaying the number of individuals in parentheses next to the point or by making the point larger or darker in proportion to the number of individuals. Finally, the straight line that best fits the points in the scatterplot, which is called the regression line, can also be included.

Figure 12.14 Sample APA-Style Scatterplot

Expressing Descriptive Statistics in Tables

Like graphs, tables can be used to present large amounts of information clearly and efficiently. The same general principles apply to tables as apply to graphs. They should add important information to the presentation of your results, be as simple as possible, and be interpretable on their own. Again, we focus here on tables for an APA-style manuscript.

The most common use of tables is to present several means and standard deviations—usually for complex research designs with multiple independent and dependent variables. Figure 12.15 “Sample APA-Style Table Presenting Means and Standard Deviations” , for example, shows the results of a hypothetical study similar to the one by MacDonald and Martineau (2002) discussed in Chapter 5 “Psychological Measurement” . (The means in Figure 12.15 “Sample APA-Style Table Presenting Means and Standard Deviations” are the means reported by MacDonald and Martineau, but the standard errors are not). Recall that these researchers categorized participants as having low or high self-esteem, put them into a negative or positive mood, and measured their intentions to have unprotected sex. Although not mentioned in Chapter 5 “Psychological Measurement” , they also measured participants’ attitudes toward unprotected sex. Notice that the table includes horizontal lines spanning the entire table at the top and bottom, and just beneath the column headings. Furthermore, every column has a heading—including the leftmost column—and there are additional headings that span two or more columns that help to organize the information and present it more efficiently. Finally, notice that APA-style tables are numbered consecutively starting at 1 (Table 1, Table 2, and so on) and given a brief but clear and descriptive title.

Figure 12.15 Sample APA-Style Table Presenting Means and Standard Deviations

Another common use of tables is to present correlations—usually measured by Pearson’s r —among several variables. This is called a correlation matrix . Figure 12.16 “Sample APA-Style Table (Correlation Matrix) Based on Research by McCabe and Colleagues” is a correlation matrix based on a study by David McCabe and colleagues (McCabe, Roediger, McDaniel, Balota, & Hambrick, 2010). They were interested in the relationships between working memory and several other variables. We can see from the table that the correlation between working memory and executive function, for example, was an extremely strong .96, that the correlation between working memory and vocabulary was a medium .27, and that all the measures except vocabulary tend to decline with age. Notice here that only half the table is filled in because the other half would have identical values. For example, the Pearson’s r value in the upper right corner (working memory and age) would be the same as the one in the lower left corner (age and working memory). The correlation of a variable with itself is always 1.00, so these values are replaced by dashes to make the table easier to read.

Figure 12.16 Sample APA-Style Table (Correlation Matrix) Based on Research by McCabe and Colleagues

As with graphs, precise statistical results that appear in a table do not need to be repeated in the text. Instead, the writer can note major trends and alert the reader to details (e.g., specific correlations) that are of particular interest.

Key Takeaways

- In an APA-style article, simple results are most efficiently presented in the text, while more complex results are most efficiently presented in graphs or tables.

- APA style includes several rules for presenting numerical results in the text. These include using words only for numbers less than 10 that do not represent precise statistical results, and rounding results to two decimal places, using words (e.g., “mean”) in the text and symbols (e.g., “ M ”) in parentheses.

- APA style includes several rules for presenting results in graphs and tables. Graphs and tables should add information rather than repeating information, be as simple as possible, and be interpretable on their own with a descriptive caption (for graphs) or a descriptive title (for tables).

- Practice: In a classic study, men and women rated the importance of physical attractiveness in both a short-term mate and a long-term mate (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). The means and standard deviations are as follows. Men / Short Term: M = 5.67, SD = 2.34; Men / Long Term: M = 4.43, SD = 2.11; Women / Short Term: M = 5.67, SD = 2.48; Women / Long Term: M = 4.22, SD = 1.98. Present these results (a) in writing, (b) in a graph, and (c) in a table.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: A contextual evolutionary analysis of human mating. Psychological Review, 100 , 204–232.

MacDonald, T. K., & Martineau, A. M. (2002). Self-esteem, mood, and intentions to use condoms: When does low self-esteem lead to risky health behaviors? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38 , 299–306.

McCabe, D. P., Roediger, H. L., McDaniel, M. A., Balota, D. A., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2010). The relationship between working memory capacity and executive functioning. Neuropsychology, 243 , 222–243.

Candela Citations

- Research Methods in Psychology. Provided by : University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Located at : http://open.lib.umn.edu/psychologyresearchmethods/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

How do I put figures (images, photos, bar graphs, charts) into my paper in APA style?

- Figures are any type of graphical illustration other than a table.

- They are used to illustrate a point and deepen readers' understanding.

Usage Guidelines:

- Figures must add to the reader’s understanding of the content of the paper; they should not be added just to provide visual interest. For more information, see section 7.22 of the APA Publication Manual (7th ed.).

- Figures must be used ethically. Copyright laws must be followed; simply citing a source does not make its use copyright compliant. A good rule of thumb: Use figures from ClipArt, Creative Commons, or the library’s rights-cleared image database, Image Quest.

References and Citations:

- You must provide complete citations for figures and tables in your paper and in your reference list.

References with NoodleTools:

- If the figure came from an image database, such as Image Quest, choose Painting, Sculpture, or Photograph from NoodleTools’s citation type drop-down menu.

- If the figure came from within a source like a book, an article, or a web site, choose a citation type that matches the source.

Citations Guidelines:

- Appears above the figure, bolded

- The number will reflect if it is the first (1), second (2), third (3), etc. figure in the paper.

- Figure Title

- The title appears one double-spaced line below the figure number in italics title face.

- The note appears below the figure and describes what the figure is about and how it relates to the content of the paper.

- If the image was taken from a source and is not clipart, the note should include a copyright attribution statement.

- If the figure was taken from source material, a reference for the figures should be included in the reference list.

EXAMPLE FIGURE

- Figure numbers are used in the text (a "call out") to refer to and explain the presence of the figures.

For more information, see:

- Writing Lab > APA Style > References > Figures (Images, Graphs)

- APA Academic Writer > Learn > Sample Figures

- Research and Library

- Last Updated Oct 08, 2024

- Views 352274

- Answered By Kerry Louvier

FAQ Actions

- Share on Facebook

Hello! We're here to help! Please log in to ask your question.

Need an answer now? Search our FAQs !

How can I find my course textbook?

You can expect a prompt response, Monday through Friday, 8:00 AM-4:00 PM Central Time (by the next business day on weekends and holidays).

Questions may be answered by a Librarian, Learning Services Coordinator, Instructor, or Tutor.

NorQuest College Library

APA 7th edition

- In-text Citations

- Reports & Government sources

- Web Resources

- Graphs, Tables & Data

- Ask a Librarian

Citing Images Tutorial

Graphs & Tables

When using graphs or tables from a published source in your assignment or PowerPoint for a class presentation , include the following:

The word Figure followed by an Arabic number in bold .

Create a brief descriptive title in italics . All titles should use title case (all major words capitalized) .

The graph or table.

Beneath the image the word Note in italics, follow by a period. Add a brief note if your graph or table needs an explanation to help the reader understand the information presented.

After the explanatory note, add the word Source, colon, parenthesis, Creator name, year of creation, page number, closed parenthesis, full stop. The format for this is as follows: Note. Explanatory note. Source: (creator, year, p.x).

Create a reference for the source you found the graph or table in. Include this at the end of your paper or presentation.

Graph example

Academic Librarian Full and Part-Time Employment, 2018

Note. Source: (Revitt et al., 2019, p. 30).

This graph was published in a report, so the format for Report, Individual author was used to create a reference entry:

Revitt, J., Magnus, E., Schrader, A., & Wright, J. (2019). 2018 census of Canadian academic librarians user guide and results summary. Canadian Association of Professional Academic Librarians. https://capalibrarians.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2018_Census_March_24_2019.pdf

Table example

Animal Preferences by Number of Responses

Note. Source: (Smith, 2018, p. 6)

Create a reference for the source. This table was published in a journal article, so the format for Journal article with a DOI has been used:

Smith, J. (2018). A study of favourite animals. Animal Journal, 3 (1), 4-16. https://doi.org/10.xxxxx/xxx/xx

- Refer to figures in text by their number (Figure 1 or Figure 2), not as "the figure below" or "the figure above".

Data & Statistics

- If you are just referring to data and statistics in an existing publication, create a citation for the source you found them in.

Author, A. (Year). Title in italics [Description in brackets]. Publisher. DOI or URL

City of Edmonton. (2021). Average monthly residential water consumption by neighbourhood 2016 - map view [Interactive map]. City of Edmonton Open Data Portal. https://data.edmonton.ca/d/b7bj-t9wu

Statistics Canada. (2017). Volatile organic compound levels measured in household air (13-10-0105-01) [Table]. https://doi.org/10.25318/1310010501-eng

- Provide a retrieval date at the end of the reference if the information is likely to change over time

- If you use a data set to conduct your own statistical analysis, or create a graph or chart that you include in your paper, create a reference for that data set specifically.

- Follow the same formatting guidelines outlined in the Graphs & Tables section above

Author, A. (Year). Title in italics (Numerical identifier and version) [Data set]. Publisher. DOI or URL

Presence of Sleep Disorders by Gender

Note. Sleep disorders according to gender as determined by a formal diagnosis from a medical professional, and not by interpreting the sleep duration and sleep quality data. Source: (Tharmalingam, 2023).

Reference entry:

Tharmalingam, L. (2023). Sleep health and lifestyle dataset (Version 2) [Data set]. Kaggle. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/uom190346a/sleep-health-and-lifestyle-dataset

Programming packages

- Include code, data and documentation that enables users to carry out specific functions

- Get the citation for an R package by following these instructions for Citing R

Author, A. (Year). Name of package in italics (version number) [Description in brackets]. Publisher. DOI or URL

Descriptive title in italics

Note. Source: (Müller, 2020).

Müller, K. (2020). _here: A simpler way to find your files_ (version 1.0.1) [R package]. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. https://cran.r-project.org/package=here

The graph and table examples are adapted from the MacEwan University APA Citation guide under a CC BY-NC license .

- << Previous: Images

- Next: Ask a Librarian >>

- Last Updated: Dec 6, 2024 2:34 PM

- URL: https://libguides.norquest.ca/apa

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Figures include all graphical displays of information that are not tables. Common types include graphs, charts, drawings, maps, plots, and photos. Just like tables, figures should supplement the text and should be both understandable on their own and referenced fully in the text.

Use graphics software to create figures in APA Style papers. For example, use the built-in graphics features of your word-processing program (e.g., Microsoft Word or Excel) or dedicated programs such as Photoshop or Inkscape.

Dec 24, 2022 · Common Types of Graphs in Research Papers Line graphs. When you want to illustrate a change over a continuous range or time, a line graph is your best choice. Changes in different groups or samples over the same range or time can be shown by lines of different colors or with different symbols.

These sample figures illustrate how to set up figures in APA Style. Note that any kind of visual display that is not a table is considered a figure. Samples include bar graph, line graph, CONSORT flowchart, path model, qualitative research figure, mixed methods research figure, illustration of experimental stimuli, and map.

Statistics and results from data analysis are often best presented in the form of a table, and a theoretical model or pages of information are often best presented in a well-designed visual such as a chart or graph. The American Psychological Association (APA) distinguishes between two types of visuals: tables and figures. Both are used…

Feb 22, 2021 · About Fabricio Pamplona. Fabricio Pamplona is the founder of Mind the Graph - a tool used by over 400K users in 60 countries. He has a Ph.D. and solid scientific background in Psychopharmacology and experience as a Guest Researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry (Germany) and Researcher in D'Or Institute for Research and Education (IDOR, Brazil).

Mar 25, 2024 · Figures in Research Paper. Figures in research papers refer to graphical or visual representations of information, data, or concepts. They are designed to complement the text by presenting information in an easily digestible and visually appealing format. Common types of figures include charts, graphs, photographs, illustrations, and flowcharts.

Third, graphs should be interpretable on their own. A reader should be able to understand the basic result based only on the graph and its caption and should not have to refer to the text for an explanation. There are also several more technical guidelines for graphs that include the following: Layout. The graph should be slightly wider than it ...

The number will reflect if it is the first (1), second (2), third (3), etc. figure in the paper. Figure Title; The title appears one double-spaced line below the figure number in italics title face. Note; The note appears below the figure and describes what the figure is about and how it relates to the content of the paper.

3 days ago · If you use a data set to conduct your own statistical analysis, or create a graph or chart that you include in your paper, create a reference for that data set specifically. Follow the same formatting guidelines outlined in the Graphs & Tables section above . Format. Author, A. (Year). Title in italics (Numerical identifier and version) [Data ...