Advertisement

Economic valuation of wildlife conservation

- Published: 10 March 2023

- Volume 69 , article number 32 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Simone Martino ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4394-6475 1 , 2 &

- Jasper O. Kenter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3612-086X 1 , 3 , 4

8402 Accesses

7 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper reviews concepts and methods for the economic valuation of nature in the context of wildlife conservation and questions them in light of alternative approaches based on deliberation. Economic valuations have been used to set priorities, consider opportunity costs, assess co-benefits of conservation, support the case for conservation in public awareness and advocacy, and drive novel schemes to change incentives. We discuss the foundational principles of mainstream economic valuation in terms of its assumptions about values, markets, and human behaviour; propose a list of valuation studies in relation to wildlife protection; and explain the methods used. We then review critiques of these approaches focusing on the narrow way in which economics conceives of values, and institutional, power, and equity concerns. Finally, we complement conventional approaches commonly used for wildlife valuation with two forms of deliberative valuation: deliberated preferences and deliberative democratic monetary valuation. These are discussed in terms of their potential to address the drawbacks of mainstream economics and to realise the potential of valuation in bridging conservation of nature for its own sake and its important contributions to human well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Tourists’ valuation of nature in protected areas: A systematic review

Economics of wildlife management—an overview

Conserving Tanzania’s Wildlife: What is the Policy Problem?

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The importance of the social sciences in shaping conservation and wildlife management and in understanding the societal implications of conservation is increasingly recognised (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005 ; Braat and de Groot 2012 ; Redpath et al. 2013 ; Sandbrook et al. 2013 ; Bennett et al. 2016 , 2017 ). As a public good, wildlife has been heavily regulated including through the designation of protected species and protected areas, customs controls for trade in protected species, and animal welfare legislation. While there have been successes, the reality of many conflicting other policy priorities and conflicting economic incentives combined with weak institutions, limited resourcing and enforcement, and de facto open access regimes have led to many governance and market failures (Pearce and Moran 1994 ; Child et al. 2012 ). Also, regulatory approaches are only effective for those species and areas that are protected. This means additional approaches are necessary to ensure that the value of biodiversity more broadly is integrated into private and policy decisions. Valuing wildlife has emerged to counter perverse incentives to land use and management strategies (or lack thereof) that deplete natural resources and erode biodiversity (Daily and Ehrlich 1992 ; Pimentel et al. 1999 ). Many conservationists now recognize that economics needs to be a part of the design and implementation of conservation policies to achieve effective conservation whilst minimising opportunity cost for communities (Shogren et al. 1999 ; Barua et al. 2013 ; Emerton 1999 ; Sementelli et al. 2008 ), to maximise co-benefits of conservation in terms of ecosystem services that benefit human well-being (Tallis et al. 2008 ), Footnote 1 and to raise awareness of the value of nature and inventorise wildlife as natural capital stocks (Costanza et al. 2014 ; Jones et al. 2016 ). The proposal of wildlife as a natural asset having an economic value as other manufactured capitals can provide new perspectives to reduce human-wildlife conflicts (Nguyen et al. 2022 ), address the compatibility between conservation and hunting (Casola et al. 2022 ; Zhou et al. 2021 ; Gascoigne et al. 2021 ; Chapagain and Poudyal 2020 ; Travers et al. 2019 ; Fischer et al. 2015 ; Nielsen et al. 2014 ), generate new funding streams and support innovative financial tools (Emerton 1999 ; OECD 2013 ) that can facilitate the correction of market and governance failures (Pearce and Moran 1994 ). It is evident from what was said above that the adoption of economics in nature management reflects the vision of conservation policy based mainly on the instrumental (anthropocentric) value of nature rooted in the Hellenic and Judeo-Christian tradition (Parks and Gowdy 2013 ). These considerations show how nature conservation is becoming as much about people and institutions as it is about ecosystems and biodiversity (Mascia et al. 2003 ).

In the last 40 years, valuation studies on wildlife protection based on hypothetical markets and the analysis of revealed preferences mainly for uses such as recreation and tourism have proliferated (see Table 1 ). In addition, meta-analyses of biodiversity valuations have been undertaken to suggest what elements might influence and better direct an efficient allocation of resources for biodiversity protection (Loomis and White 1996 ; Martin-Lopez et al. 2007 ; Richardson and Loomis 2009 ).

However, due to the failure of policy initiatives to curb the loss of biodiversity and increasing emphasis on understanding multiple values in platforms such as the Intergovernmental Science Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), new paradigms based on a closer synergy between “nature and people” (Mace 2014 ; Garcia-Jimenez et al. 2021 ) are advocated, and bio-cultural, deliberative and shared value approaches to conservation emphasise the need for pluralistic and partnership-based ways of conserving nature (Kenter 2016b ; Gavin et al. 2018 ; Christie et al. 2019 ; Diaz et al. 2018 ). Related to this, many critiques have been raised with traditional economic approaches. These include concerns about the public ability to understand and value biodiversity and what components can be feasibly expressed in monetary units (Nunes et al. 2001 ; Christie et al. 2006 ); concerns around the commodification of nature (McCauley 2006 ; Gómez-Baggethun and Ruiz-Pérez 2011 ); justice concerns around the prioritisation of certain values over others (Matulis 2014 ), and philosophical and psychological questioning of the narrow individualistic and utilitarian value assumptions of conventional (neoclassical) economics (O’Neill et al. 2008 ; Kenter et al. 2015 ). The emerging debate has given rise to novel approaches to valuation that seek to integrate shared, social and cultural values into valuations and decision-making. Here, group deliberation to form and bring together plural values plays an important role.

In this paper, we review the use of economic valuation in the context of wildlife conservation, outlining key concepts and methods illustrated with case examples identified through a structured literature review. Then we briefly review key critiques and concerns, before considering how recent deliberative approaches have attempted to address some of these concerns. The aim of this paper is to (1) provide an overview of economic valuation in a succinct and understandable way to those engaged in conservation science; (2) demonstrate the diverse way by which valuation is used to support wildlife protection in different contexts and regions; and (3) highlight novel deliberative approaches in valuation that could help bridge the increasing focus on human benefits of conservation with the value of wildlife as a good in and for itself. While there are various existing reviews of environmental valuation and a small number of reviews of deliberative monetary valuation (Spash 2008a , b ; Bunse et al. 2015 ), this is the first to specifically focus on wildlife conservation, and to provide an empirical overview of both traditional and deliberative economic studies.

Economic concepts to valuing biodiversity and wildlife

In the absence of human judgments, neoclassical economics suggests that goods and services in themselves have no value (Parks and Gowdy 2013 ), with valuation being the process of assessing preferences that express judgements on the value of goods. Therefore, only human preferences are recognised as the source of economic value (Mitchell and Carson 1989 ). Values of things, expressed as preferences, are thought to reflect the benefit of one additional unit of a good, keeping the amount of all other goods constant. This “marginalistic” notion of values relates to the conception of continuous exchange and trade-offs of goods or services within the market to maximise preference satisfaction (Lawson 2013 ). Trade-offs of goods against money are known as willingness to pay (WTP), the preferred measure of the intensity of preferences. Its counterpart, willingness to accept (WTA) provides another indication of our preferences towards goods in terms of how much we would need to receive in lieu of relinquishing something of value to us. Through this monetary expression of preferences, the market is thought to “invisibly” achieve the most efficient distribution of goods for society, optimising the allocation of scarce resources per those most willing to pay for them. Several further important assumptions are made. Preferences are considered purely individual and self-regarding, and neoclassical economics does not take an interest in what motivations underlay preferences, and values are considered pre-formed and rational. Value to society is established by aggregating individual values, usually through the simple addition of WTP (Hockley 2014 ).

When values associated with goods and services arising from nature are not accounted for in markets and policy because they are not traded, the resulting allocation of goods is inefficient. This is a situation that economists call market failure , and this has been an important impetus for extending the application of economic valuation to the environment. While adhering to a moral norm that biodiversity is basically good is an understandable position for many conservationists (Meffe and Caroll 1994 ), from a neoclassical economic perspective of value, only the biodiversity that provides benefits to humans that are marginally more valuable than the costs of implementing protection policies (including opportunity costs) should be protected (Roughgarden 1995 ). If conservation comes at the expense of alternatives that have a greater economic value to society, opportunity costs occur and justification for such a position would thus need to be made on non-economic grounds.

Typical examples of market failure include subsidisation of farming and ranching that make these activities more profitable than they would otherwise be, at the cost of undervalued wildlife (Emerton 1997 ; Child et al. 2012 ). Reverting this market distortion is possible by introducing different incentives motivating landowners to consider wildlife as a valuable asset that, if protected, can generate higher profits, including benefits from hunting that would make it compatible with conservation (Zhou et al. 2021 ; Chapagain and Poudyal 2020 ; Travers et al. 2019 ; Fischer et al. 2015 ; Nielsen et al. 2014 ) than land use that negatively affects those assets (e.g. intensive farming). This approach can also be applied to marine and terrestrial protected areas (McNeely 1993 ; Emerton 1998 ; Child, et al. 2012 ) that traditionally have been supported by public money. Thus, from an economic perspective, under non-distorted or corrected markets, competition for products and services drives prices of different uses for ecosystems by recognising the relative benefits of conservation and consequently making it a more attractive option (Loomis 1993 , 2000 ).

Environmental economists classify values according to the heuristic of Total Economic Value (Turner et al. 2003 ), which is split into two main categories: use and non-use values (Arrow et al. 1993 ). Use value includes non-consumptive use value such as that generated by recreational experience (Carr and Mendelsohn 2003 ; Becker et al. 2005 ; Getzner 2015 ; Chapagain and Poudyal 2020 ; Frew et al. 2018 ; Gascoigne et al. 2021 ) and consumptive use value such as from hunting (Berman and Kofinas 2004 ; Bennett and Whitten 2003 ). In addition, wildlife provides option value , the nominal price that one is willing to pay to safeguard potential future use (Pearce and Turner 1989 ). Non-use values, also called passive use values, include value for the sake of knowing that others ( altruistic value ), future generations ( bequest value ), or non-human nature ( existence value ) benefit (Ojea and Loureiro 2007 ; Saayman 2014 ; Morse-Jones et al. 2012 ; Molina et al. 2019 ). Altruistic, bequest, and existence values are, in neoclassical economics, still considered as self-regarding and not truly altruistic because it is solely the satisfaction to the person of having their preferences maximised that is assumed to be of value (Kenter 2015 ; Kenter et al. 2015 ; Kenter et al. 2016a ).

Finally, it is helpful to note that natural scientists and economists tend to consider biodiversity from different perspectives. While ecologists consider biodiversity as a representation of the complexity of the ecological system (Farnsworth et al. 2012 , 2015 ), the most common conceptions used by economists refer to specific biological components of diversity (Pearce and Moran 1994 ) such as the number or richness of species, threatened or endangered species, genetic resources of value, and ecosystem functions and services provided by ecosystems and single species (Bartkowski et al. 2015 ; Garcia-Jimenez et al. 2021 ; Markandya et al. 2008 ; Margalida et al. 2012 , 2010 ; Morales-Reyes et al. 2015 ; Becker et al. 2005 ). Consequently, environmental valuation typically refers to monetisation of the preferences in relation to these common indicators of biodiversity rather than systemic concepts of resilience and ecosystem stability (Christie et al. 2006 ; Farnsworth et al. 2015 ).

Economic valuation methods and applications to wildlife conservation

Building on the concepts discussed in the previous section, environmental economic valuation aims to assess individuals’ preferences, either stated or revealed (Turner et al. 2003 ). Stated preferences approaches, primarily including the contingent valuation method (CVM) (Hanemann 1994 ) and choice experiments (CE) (Birol et al. 2006 ), elicit respondents’ preferences in hypothetical scenarios, where they are asked either for their WTP for conservation, or (less commonly) their WTA for the loss of wildlife. They are the only method that is considered to effectively deal with non-use values (Arrow et al. 1993 ). In CVM, people are asked to directly state their WTP or WTA in relation to a clearly described environmental or policy change (e.g. for the conservation of charismatic species such as rhino (Saayman and Saayman 2017 ), Iberian and Eurasian lynx (Bartczak and Meyerhoff 2013 ; Molina et al. 2019 ) or sea turtle (Cazabon-Mannette et al. 2017 )). In CE, respondents are asked to consider several alternatives, described on the basis of multiple attributes, typically with a monetary cost attached to them and with a status quo at no cost. In CE, WTP is assumed to reflect the marginal rate of substitution between non-monetary attributes and the cost attribute. Several studies use CE to explore attributes of different policy measures that can reduce trade-offs between conservation, recreation, and hunting. To make a few examples, Bach and Burton ( 2017 ) use a choice experiment to explore trade-offs between conservation measures and recreational aspects of wildlife interactions with dolphins, while Nguyen et al. ( 2022 ) consider the possibility to reduce wildlife-human conflicts and Nielsen et al. ( 2014 ) and Travers et al. ( 2019 ) the possibility to implement measures that limit illegal hunting and trade of bush meat. Conventionally, stated preference methods are conducted via questionnaires, but there is increasing interest in deliberative monetary valuation (DMV) approaches (see “Discussion and conclusions” section), where people state their values after group discussions (Bunse et al. 2015 ).

Revealed preferences approaches use observed market data on an ordinary commodity to infer preferences for marginal changes in the quality or quantity of an environmental good associated with the ordinary commodity (Bockstael and McConnell 1993 ). Two key approaches include the hedonic pricing method (HPM) and travel cost method (TCM). With HPM the value of the environmental goods (e.g. the value of charismatic wildlife) is measured as a marginal impact on the value of immobile assets (typically premises or land) as in Casola et al. ( 2022 ) who investigated the marginal impact on property price caused by proximity and adjacency to hunting areas. In the case of TCM, preferences are revealed from money spent on travelling and the number of visits to a certain area to derive the recreational experience (Perman et al. 2003 ) as a measure of welfare accompanied by the economic impacts of recreation as direct spend and job creation (Frew et al. 2018 ; Fischer et al. 2015 ; Gascoigne et al. 2021 ).

Other approaches that are not based on preferences are also used in environmental valuation, though they are much less commonly used in relation to wildlife conservation. Production function approaches were commonly used during the 1990s to address the impact that natural capital might have on marketable outputs. Here the environment is treated as an “input” to the economic activity and its value is equated, like any other input, with the impact it has on the productivity of a marketed output. For example, Barbier ( 2000 ) looked at the value of regulating services such as nursery and habitat functions of mangroves in supporting the fishing shrimp industry in south Thailand and Mexico. Finally, approaches based on cost, such as avoided damage-cost, and replacement cost can be used for wildlife valuation. In the avoided damage-cost method, the benefits that are valued are considered at least equal to avoided damages, for example where natural predators control pests. An example of avoided cost provided by the conservation of vultures is shown by Markandya et al. ( 2008 ) who monetized the avoided cost of illness in terms of reduced bubonic and rabies diseases caused by stray dogs in India if vultures were protected. In the replacement cost method, minimum values of environmental goods are equated with the cost of replacing them with human solutions. For example, the cost of hiring honey beehives can be considered a proxy for the value of the services provided by wild pollinators (Sandhu et al. 2008 , 2015 ). Taxes and fines have also been used in some cases as a proxy for wildlife values, including non-use values (Sterner 2009 ), but they may be significantly less than values elicited through stated preference approaches. For example, the highest fine mandated by the 1973 US Endangered Species Act is $50,000, much lower than $173,209 considered as efficient to address the optimal level of protection of threatened and endangered organisms (Eagle and Betters 1998 ).

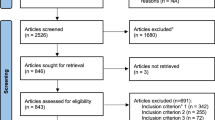

To illustrate the use of stated and revealed preference methods, we conducted a literature search of the last 30 years of research Footnote 2 on valuation considering method, species, type of value, geographic area, and motivations behind the study. The review was not meant to be fully comprehensive, but illustrative of the types of studies that have been undertaken to value wildlife. Searches were conducted on the Web of Science platform (searching in the fields “Title”, “Abstract”, and “Keywords”) using “wildlife” and “economics”, “contingent valuation”, “choice experiment” “travel cost method”, “hedonic price”, “deliberative monetary valuation” as search strings. Studies on habitat conservation, biodiversity, and in general terms to ecosystem services without reference to animal species were not included. In total, 150 studies emerged as based on conventional, non-deliberative stated, and revealed preference methods. A sample of these studies, organised by species and aim, is provided in Table 1 . The full set of studies is proposed in the Supplementary material. In addition, fourteen studies that conducted deliberative monetary approaches directly or indirectly related to wildlife protection were discussed separately in Section " Discussion and conclusions ".

Fifty per cent of the sample reported by our search used CVM, 27% used CE, 19% used TCM, 2% used HPM and the remaining 2% are more articulated valuation-based studies addressing the analysis of cost as a proxy for benefits, implementation of cos-benefit analysis with consideration of opportunity costs, or combination of market values with non-market price analysis. We found a relatively homogeneous distribution of studies (nearly 35 per continent) across Europe, the Americas, and Asia. Africa showed 25 studies, Oceania 22. CVM studies were dominating 20–30 years ago, now CE is equally prominent.

Table 1 shows how the literature has mainly focussed on mammals in temperate habitats (Johansson et al. 2012 ; Han and Lee 2008 ) and on the charismatic species of tropical countries (Saayman and Saayman 2014 ; Kaffashi et al. 2015 ; Rathnayake 2016 ; Wang et al. 2018 ), while less cases have been recorded in the marine (Saayman 2014 ; Batel et al. 2014 ; Pires et al. 2016 ; Nuno et al. 2018 ) and freshwater environments (Gan et al. 2011 ; Hutt et al. 2013 ).

Common patterns arising from Table 1 show that early studies (1980s and 1990s) addressed WTP drivers of wildlife conservation, while more recent research (since the 2000s) focuses more broadly on biodiversity and management tools such as taxes to protect bottlenose dolphin (Batel et al. 2014 ), hunting licences for elk and deer (Fix et al. 2005 ), and entrance fees for managing elephant conservation (Rathnayake 2016 ). Single species valuation is mainly carried out by CVM for the conservation of griffon vulture (Becker et al. 2005 , 2009 ), dolphin (Wang et al. 2016 ), catfish (Hutt et al. 2013 ), red grouse (Hanley et al. 2010 ), deer (Hanley et al. 2003 ), duck (Whitten and Bennett 2002 ), Eurasian lynx (Bartczak and Meyerhoff 2013 ; White et al. 2015 ) and Iberian lynx (Molina et al. 2019 ). Additional analysis refers to non-use value preservation of the big five (Kaffashi et al. 2015 ) and the big seven (Saayman and Saayman 2014 ).

CEs are used to relate wildlife conservation to contextual factors such as forest and wetland habitats management (Bergmann et al. 2006 ; Dias and Belcher 2015 ; Petrolia et al. 2014 ), or projects impacting the ecosystems and landscape such as renewable energies (Emmanouilides & Sgouromalli 2013 ; Ku and Yoo 2010 ; Lundhede et al. 2015 ). Use values of wildlife such as recreation (Zhou et al. 2021 ; Frew et al. 2018 ), viewing, and gaming are also frequently assessed by TCM (Gascoigne et al. 2021 ; Bennett and Whitten 2003 ), while only four papers have been found using HPM, all in relation to wildlife and hunters’ policy, assessing values of hunting licences (Lundhede et al. 2015 ; Getzner 2015 ; Mensah and Elofsson 2017 ; Casola et al. 2022 ). Studies addressing the relationship between wildlife viewing and hunting have shown benefits to individuals and society far greater than its realised economic earnings (Chapagain and Poudyal 2020 ; Frew et al. 2018 ; Fischer et al. 2015 ; Gascoigne et al. 2021 ), providing an opportunity to inform the value of taxes to better reflect consumer surplus arising from the recreational experience (Navrud and Mungatana 1994 ; Kaffashi et al. 2015 ); generating insights on new policy attributes that my help reduce the impact of illegal hunting and bush meat trade (Nielsen et al. 2014 ; Travers et al. 2019 ); raising awareness on the possible win–win solutions between conservation, recreation, and hunting (Gascoigne et al. 2021 ; Fischer et al. 2015 ); and addressing conflicts, to mention one specific case, between human communities and elephants (Nguyen et al. 2022 ). In addition, examples from southern Africa dryland ecosystems suggest that wildlife conservation in private ranches is becoming more remunerative than modern livestock production (Jenkins 2011 ; ABSA 2015 ) under communities’ right to use and benefit from wildlife (Child et al. 2012 ).

The literature explored revealed that CVM or CE is not mere econometric exercises. Studies frequently are designed for management purposes such as the implementation of market tools: entrance fees (Barnes et al. 1999 ; Fix et al. 2005 ; Stanley 2005 ; Mmopelwa et al. 2007 ; Cerda 2011 ; Kaffashi et al. 2015 ; Rathnayake 2016 ); property/user rights (Horne and Petajisto 2003 ; Sutton et al. 2008 ; Harihar et al. 2015 ); taxes to induce recreationalist behavioural changes in marine protected areas (Batel et al. 2014 ) and for terrestrial non-game conservation (Dalrymple et al. 2012 ). In addition, it is frequent the analysis of transaction and opportunity costs of wildlife conservation for communities (Barua et al. 2013 ; Emerton 1999 ; Sementelli et al. 2008 ) along with social valuations (Delibes-Mateos et al. 2022 ) in environmental cost–benefit analysis of policy scenarios, for instance, related to the analysis of the reintroduction of the Eurasian lynx in the UK (White et al. 2015 ; Hawkins et al. 2020 ).

Aside from the management implication of valuation, a set of studies investigated the motivations driving WTP, focusing on the role of socio-economic factors (Teal and Loomis 2000 ; Travers et al. 2019 ; Fischer et al. 2015 ; Nielsen et al. 2014 ), the knowledge of species endangerment (Tisdell and Wilson 2004 ; Tisdell et al. 2005a ; Morse-Jones et al. 2012 ), the degree to which people show appreciation for species (Tisdell et al. 2005b , 2007 ) or ethical aspects affecting WTP (Martinez-Espineira 2006 ; Ojea and Loureiro 2007 ).

Finally, benefit transfer methods were applied to inform benefits from a number of prior study sites to other locations where new primary studies are not feasible (Spash and Vatn 2006 ). A meta-analysis carried out by Loomis and White ( 1996 ) concluded that CVM provides estimates sensitive to the size of the endangered species population. Other meta-analyses identified a number of factors that help predict WTP for biodiversity conservation, including preferences for certain phylogenies (mammals and birds are preferred over reptiles) and economic effect of species such as damage to agriculture, which appeared to be more important than IUCN red list classification (Martin-Lopez et al. 2007 ; Richardson and Loomis 2009 ).

Notwithstanding the benefits of protection, wildlife conservation can be opposed and considered costly in case of predation on livestock, destruction of crops, traffic collisions, and transmission of diseases to animals and humans (Gren et al. 2018 ). Increased land use for agricultural purposes, occurring mainly in developing countries, also raises this type of conflict (Madhusudan 2003 ; Ninan and Sathyapalan 2005 ). However, there is evidence as reported in Table 1 of the benefits of conservation in comparison with the cost of protection such as for Griffon vulture (Johansson et al. 2012 ; Garcia-Jimenez et al. 2021 ; Markandya et al. 2008 ; Morales-Reyes et al. 2015 ; Becker et al. 2005 ), elephant (Sutton et al. 2008 ), deer (Bowker et al. 2003 ), and duck (Bennett and Whitten 2003 ). The latter examples show that valuation is often not an independent exercise, but more typically part of Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA), a way of appraising a policy by assessing the anticipated net benefits and costs (or ratio of benefits to costs) arising from its implementation. In conservation, benefits are often non-marketed values that can be addressed only by applying the methods above illustrated (Shwiff et al. 2013 ). These values are usually aggregated over a particular time span by discounting future values to the present, and for each affected party at stake, as shown for the reintroduction of the Eurasian lynx in the UK (White et al. 2015 ; Hawkins et al. 2020 ). Notwithstanding critiques of methods of valuation and aggregation, as reported in the next section, the range of economic approaches in Table 1 demonstrates the potential for economics to inform conservation policy and practice. This is achieved by an understanding of the human benefits and costs and potential trade-offs of conservation, and how incentives can change human behaviour and land management in a way that can enhance both conservation and economic outcomes.

Critiques of economic valuation

While the economic valuation of the benefits that wildlife provides to human well-being has been advocated as a powerful approach to enhance public, landowner, business, and policy support for conservation, it has equally received fierce criticisms. These critiques range broadly (for overviews see Forster 1997 ; Ravenscroft 2010 ; Kallis et al. 2013 ; Parks and Gowdy 2013 ; Matulis 2014 ; Schröter et al. 2014 ), but many of these issues can be related to either the narrow neoclassical economic conceptions of human values or to institutional questions of power and justice.

Value plurality

A key critique of mainstream environmental valuation relates to the conception of the consumer as a “rational agent” characterised by independent and exogenous preferences. It is highly questionable whether all values and behaviour can be couched in terms of pre-formed, self-regarding individual preferences that are rationally traded-off (Bowles and Gintis 2000 ; Balaine et al. 2020 ; Isacs et al. 2021 ). In relation to the natural environment, peoples’ motivations are very diverse, including rights, duties, virtues, cultural beliefs, identities, and narratives that are hard to translate into measures of utility (Spash 2006 ; Ojea and Loureiro 2007 ; Cooper et al. 2016 ). For example, people might be willing to pay for something because they feel it is the right thing to do, rather than because it satisfies their individual preferences. Moreover, many shared values operate at the level of communities and cultures, rather than individuals (Irvine et al. 2016 ), while the utilitarian framework assumes preferences can be counted in terms of individuals and added up. Even at the individual level, people may have multiple types of values that are difficult to compare. Ecological economists have proposed that irreducible value conflict is unavoidable and that only practical judgment formulated by deliberation provides an appropriate means for rational comparison (Martinez-Alier et al. 1998 ; Isacs et al. 2021 ). Furthermore, people may find it hard to understand biodiversity and ecosystems (Nunes et al. 2001 ; Christie et al. 2006 ; Hanley et al. 2015 ), often do not have clearly pre-formed values (Kenter et al. 2016c ), and may themselves prefer values to be expressed through group deliberation, to shape decisions under societal perspectives rather than that of individual consumers (Sagoff 1998 ; Ward 1999 ; Shapansky et al. 2003 ; Martinez-Espineira 2007 ; Bunse et al. 2015 ; Lienhoop et al. 2015 ; Kenter et al. 2016b ; Orchard-Webb et al. 2016 ).

Epistemologically, neoclassical economic approaches do not usually recognise pluralistic values and tend to exclude subjective and qualitative material (Parks and Gowdy 2013 ; Isacs et al. 2021 ). Economic studies focus on what is valued and how much , with little attention given to the why people value particular elements of nature in particular places. Economic conceptions and approaches for many violate a sense of integrity of nature, where the sacred, sublime, and aesthetic are reduced to mere numbers, and intrinsic values and rights of non-human nature are reduced to preferences (Cooper et al. 2016 ). It has been argued that the description of the environment in terms of preferences, utility, and WTP, at the least fails to reflect the deeper and often shared meanings that places might hold (Owen et al. 2009 ; Daniel et al. 2012 ) and at the worst is in itself a political act of commodification and enclosure (McCauley 2006 ; O’Neill et al. 2008 ; Gomez-Baggethun and Ruiz-Perez 2011 ; Turnhout et al. 2013 ; Matulis 2014 ; Spash 2015 ). A key risk of commodification is that, where human ingenuity can replace ecosystem services, the ecosystems providing those services lose their intrinsic value (Kronenberg 2015 ). However, other authors argue that a degree of commodification is necessary to embed the protection of services in a market context (TEEB 2010 ; UK NEA 2011 ) and to facilitate long-term behavioural changes towards nature conservation (Burton and Schwartz 2013 ).

Power, justice, and institutional critiques

In relation to conservation, there are many different dimensions of value that are difficult to trade-off against each other, raising the questions of power and justice in economic valuation. Such critiques of neoclassical economics focus on concerns with the role of cost–benefit analysis (CBA) in informing public policies (Hockley 2014 ) and assumptions that social welfare is measured by the sum of preferences of independent individuals (Parks and Gowdy 2013 ). When aggregating values, an agreement is needed on how to cluster within dimensions (i.e. how much does each individual count), and across dimensions of valuation (i.e. how are different value criteria to be made commensurate). Typically, CBA assumes that different groups in society have the same weight, but this can exacerbate social disparities with the poorest gaining less than the richest (Pearce et al. 2006 ). Another challenge is about what constitutes values: dimensions of value could be a set of straightforward economic or financial benefits and costs (e.g. expected revenue, construction, and operational costs), but the livelihoods of people, the cultural impact of the project, and impacts on local biodiversity cannot be easily monetised and used in CBA. In conventional economic analysis, if the benefits outweigh the costs after the compensation of losers, the project would be ‘efficient’ and deliver a net value to society (regardless of whether these compensations actually take place). This assumes that, in principle, the ecological, social, and cultural dimensions of value can be monetised and compensated fully and justly. However, unless all parties can agree on how different dimensions should be traded-off against each other, it is not possible to come to any single conclusion. Some economists themselves have argued that for this reason, economic valuation and appraisal have only limited use in complex and contested situations (Hockley 2014 ). People often resist attempts for their values to be converted into monetary amounts, and as a result, the use of economic approaches can increase conflict rather than resolve it when people feel that their other values are not taken into consideration (O’Brien 2003 ; Martino et al. 2019 , 2022 ). In more complex situations, collective choices taken in the interests of the community rather than economic transactions may dominate decisions and reduce the scope for economic valuation and CBA (Ostrom 1990 ).

To overcome these issues, frameworks of resource allocation and appraisal need to move beyond questions of preference utilitarian-based economic efficiency alone; for example, Turner ( 2016 ) proposes a ‘triple balance sheet’ framework to take account of shared and plural values, equity and justice, in those complex circumstances where the standard CBA is not considered adequate. This framework provides a basis for individuals and groups to work towards agreements from initially contesting positions (Bromley 2004 ), overcoming institutionalised economic analyses that are in most cases non-participatory (Christie et al. 2012 ) and limit their perceived democratic legitimacy (Hockley 2014 ). Even when CBA is appropriate, moving towards a more equitable CBA is now recognised as essential (Pearce et al. 2006 ; Turner 2007 , 2016 ) and examples are emerging, for instance in the context of climate change (van der Bergh and Botzen 2014 ; Nordhaus 2017 ).

Finally, it is important to note that there is confusion about the normative aim of valuation. The ultimate ecological goal of sustaining resilient ecosystems is not necessarily aligned with valuing biodiversity (Farnsworth et al. 2012 , 2015 ; Bartkowski et al. 2015 ). Although many environmental economists, and increasingly conservationists, see valuation as a means to an end, whereby the end is conservation (Spash and Aslaksen 2015 ), this end is different from economists’ goal of informing implications for human welfare, albeit defined within the narrow terms of utility and efficiency. While many economists seem to think the two can be harmonised (Kenter 2016b ), economic analysis may not favour conservation action. For example, van Beukering et al. ( 2014 ) valued the benefits and costs of a project to eradicate invasive species from a conservation area in Montserrat through a choice experiment approach but found that people’s preferences were lined up against this. This resonates with fundamental questions about whether the common good, as an objective of public policy, can really be equated with aggregate benefits to individuals (Sagoff 1998 ), and the degree to which individual preferences can account for a long-term sustainability perspective, also where understanding of ecological processes is limited to experts. Thus, in conventional economic approaches, when people’s utilitarian preferences do not align with long-term sustainability, we cannot expect approaches based on such preferences to lead to sustainable outcomes (Norgaard 2010 ; Everard et al. 2016 ).

- Deliberative monetary valuation

To address the issues above described, several different ways forward are being pursued. These include (1) the development of frameworks of environmental values that move beyond individualism and utilitarianism (Spash 2008b ; Chan et al. 2012 , 2016 ; Kenter et al. 2015 , 2019 ; Scholte et al. 2015 ; Pascual et al. 2017 ; O’Connor and Kenter 2019 ; Kenter and O’Connor 2021 ); (2) non-monetary valuation approaches, as an alternative to economic ones (Raymond et al. 2014 ; Ranger et al. 2016 ), to generate multiple evidence bases (Tengö et al. 2014 ; Hattam et al. 2015 ), or integrated with monetary valuation (Jacobs et al. 2016 ; Kenter 2016c ; Kenter et al. 2016b ); (3) development of deliberative valuation institutions (MacMillan et al. 2002 , 2006 ; Spash 2007 , 2008a , b ; Lo and Spash 2012 ; Kenter et al. 2014 , 2016a , c ; Bunse et al. 2015 ; Orchard-Webb et al. 2016 ; Kenter 2017 ; Bartkowski and Lienhoop 2018 ; Schaafsma et al. 2018 ).

Considering the focus of the paper on economic valuation, the interest here shifts to an emerging set of methodologies termed deliberative monetary valuation (DMV), a term first employed by Spash ( 2007 ). Deliberative approaches are a way to clearly form and express preferences (e.g. Alvarez Farizo et al. 2007 ; Lliso et al. 2020 ), providing an opportunity to engage with a broader array of motivations and moral stances than utilitarian individual preferences alone (e.g. Kenter et al. 2011 ). Also, most biodiversity is set in a non-western context, where conventional survey-based approaches may be inappropriate or ineffective because of cultural differences and lower levels of literacy that can be addressed by linking participation and valuation through deliberation (Christie et al. 2012 ). DMV approaches integrate participation, reflection, discussion, and social learning into the monetary valuation of environmental and other public goods, or budgetary decisions relating to the provisioning of such goods. In DMV, small groups of participants explore values and preferences for different policy options through reasoned discourse. Values may be expressed (Table 2 ) distinguishing across two dimensions (Spash 2007 ): the value provider (individual vs. group) and scale (individual vs. societal). This schematic thus suggests four main types of monetary value indicator: (i) a deliberated individual WTP, (ii) a ‘fair price’, and a deliberated social WTP (i.e. value to society) determined by either (iii) individuals or (iv) the group. Most DMV studies have used individual WTP (Bunse et al. 2015 ), including in wildlife conservation (Table 3 ). In contrast, social WTP constitutes a pre-aggregated value to society, established through consensus or voting, on how much participants think society should spend on one thing over another, by deciding how much of a budget should be allocated to the provisioning of different public goods. In a fair price payment valuation, participants state what they think both others and themselves should pay, and thus also brings in more of a moral context than conventional elicitation of individual WTP. Moreover, the deliberative forum provided by DMV provides an opportunity to link monetary valuation to non-monetary methods where participants can express and relate values more broadly. For example, the UK National Ecosystem Assessment, whilst establishing the value of protecting wildlife and habitats in marine protected areas, linked monetary valuation to storytelling and wellbeing indicators to consider experiences, identities, and capabilities arising from the places people visited, as well as a values compass to reflect on the broader principles and life goals that MPA management should be aligned with (Bryce et al. 2016 ; Kenter et al. 2016b ).

Kenter ( 2017 ) divides DMV studies into two main types, though some have features of both: deliberated preferences approaches, where deliberation is integrated into stated preferences, and deliberative democratic monetary valuation (DDMV), where assumptions of neoclassical economics are relaxed and the focus is to deliberate directly on the common good. Deliberated preferences studies focus on providing research participants time to discuss and think about their preferences, and help participants become more familiar with the environmental goods they are being asked to value (Christie et al. 2006 ). This concern was the main motivation for some of the first empirical DMV papers, where DMV was conceptualised as a “market stall” facilitating participants to become familiar with the goods they had to value, as first applied by Macmillan et al. ( 2002 ) to study the value of wild goose conservation in Scotland.

Table 3 provides an overview of DMV studies relevant to wildlife conservation, most of which constitute deliberated preference approaches, linking CVM or more occasionally CE to deliberation. We found only seven cases of wildlife valuation via DMV (McMillan et al. 2002 ; McMillan et al. 2006 ; Philips and McMillan 2005 ; Lienhoop and Fischer 2009 ; Watzold et al. 2008 ; Kenter 2016c ; Kenter et al. 2016b ), although other studies are related to wildlife in the broader context of conservation in agriculture, marine, forest, river, and wilderness environments (Lienhoop and McMillan 2007 ; Zsabo 2011 ; Vargas and Diaz 2017 ; Vargas et al. 2017 ; Kenter et al. 2011 ; Lliso et al. 2020 ; Orchard-Webb et al. 2016 ). Deliberated preferences are focusing on the conservation of broader biodiversity and ecosystem services and the scope for preferences elicitation in the context of complex decisions affecting multiple environmental attributes (also see Bunse et al. 2015 ; Schaafsma et al. 2018 ; Lliso et al. 2020 ). Another context where deliberated preferences are promising is in relation to unknown underwater wildlife and habitats, where the absence of preformed preferences is even more of an issue (Spash 2002 ; Hanley et al. 2015 ; Jobstvogt et al. 2014a , b ). A DMV study with scuba divers and sea anglers demonstrated that even these expert participants, who were much more familiar with marine environments than the general public, lacked well-developed preferences, but they were able to develop habitat-specific preferences through group discussion (Kenter et al. 2016a ).

To address the critiques in relation to value plurality, institutions, equity, and power discussed in the previous section, DDMV approaches make a more radical departure from conventional economic assumptions. In DDMV participants consider the benefits and costs of different policy options alongside non-instrumental concerns, including social norms, rights, and duties, virtues such as fairness or responsibility, and narratives—stories that can implicitly and explicitly express values (Kenter 2017 ). While this process has been termed preference moralisation (Lo and Spash 2012 ), the values involved are more than just moral values because they address broader conceptions of what is important in life, what Kenter et al. ( 2015 ) and Raymond and Kenter ( 2016 ) term transcendental values, relating to shared communal, cultural and societal values and also to the relations between environment and culture. These values are often latent, emphasising the need for explicit consideration in deliberation. Evaluation in DDMV takes place through communicative rather than instrumental rationality, where the common good is conceived of as ultimately a question of communication and deliberation to find common agreement (Orchard-Webb et al. 2016 ).

There has been one DDMV study referring to wildlife, where participants in deliberation on hypothetical policy options for strategic local development around fisheries and the broader coastal environment established a social WTP (Orchard-Webb et al. 2016 ). This demonstrated that participants can indeed set their individual utility aside to negotiate social WTP for policy options that reflect a range of value types and concerns. The key ground on which to assess whether such valuations are rational is whether all salient perspectives and interests have been included, and outcomes are not distorted by power relationships (Howarth and Wilson 2006 ). The aim is to create a democratic platform for evaluating options across different types of ethical and practical stances and for integrating intrinsic values of wildlife into the valuation process because the final value indicators are not conceived of as representing the sum of individual utilities but as an expression of shared values and social priorities.

Thus, an important concern with DDMV and DMV generally is who sits at the table and how can their inclusive, noncoercive participation be ensured (Kenter 2017 ; Schaafsma et al. 2018 ; Zimmerman et al. 2021 ). Fortunately, DMV can build here on well-established traditions of broader deliberative and participatory research and practice in e.g. political science, development studies, and stakeholder participation in environmental management (e.g. Chambers 1997 ; Jordan 2014 ; Devente et al. 2016 ), and guidance for best practice is starting to emerge (Kenter et al. 2016a , b , c ; Schaafsma et al. 2018 ).

Adapted with modifications from Kenter ( 2017 ), originally adapted with modifications from Spash ( 2007 , 2008a , b ).

Discussion and conclusions

This paper has discussed the role of economic valuation in the context of wildlife conservation by proposing a broad range of studies from several geographic regions and for different environmental domains and species. The proposed review can provide to the community of researchers and practitioners operating in the field of wildlife conservation an important instrument for the dissemination and synthesis of the existing literature on economic valuation with implications for policy and regulating mechanisms and tools necessary for the protection of wildlife. In addition, this paper, for the first time, to the best knowledge of the authors, suggests looking at an economic valuation under a different lens by proposing key critiques of traditional mainstream valuation methods and considering how recent deliberative approaches are able to address some of the concerns raised.

The first part of this review has dealt with the role of classical economics methods for measuring the welfare of wildlife conservation and suggested how economic valuation of wildlife can help address market failures that lead to the depletion of finite natural resources and the decline of biodiversity (Daily and Ehrlich 1992 ; Pimentel et al. 1999 ) through the elicitation of environmental values driven by people’s behaviour. These methods have been used, among others, to set priorities and innovative policy attributes that show people’s motivation for conservation against resources depredation (Gascoigne et al. 2021 ; Delibes-Mateos et al. 2022 ; Nielsen et al. 2014 ; Travers et al. 2019 ; Zhou et al. 2021 ), to promote awareness of the value of nature and wildlife as natural capital stocks (Costanza et al. 2014 ; Jones et al. 2016 ), to generate new funding streams and financial tools (Emerton 1999 ; OECD 2013 ) and to set taxes and fees for promoting behavioural change (Emerton 1999 ; Sterner 2009 ; Batel et al. 2014 ; Batel et al. 2014 ; Dalrymple et al. 2012 ) in order to correct market failures (Pearce and Moran 1994 ).

Many studies have been promoted to support the case for conservation in public awareness and advocacy, facilitating where possible the setting of policy measures that may induce the coexistence between conservation, recreation, and hunting. Recent examples from around the world have used valuation approaches for addressing conservation-hunting duality in species like duck (Bettett and Whitten 2003 ), swan (Frew et al. 2018 ), elk (Chapagain and Poudyal 2020 ), lynx (Molinaet al. 2019 ; Bartczak and Meyerhoff 2013 ), grey wolf (van Eeden et al. 2021 ) and brown bear (Richardson and Lewis 2022 ) to mention a few, and reduction of wildlife-human conflicts addressing the balance between benefits and costs of reintroducing the Eurasian lynx in the UK (White et al. 2015 ; Hawkins et al. 2020 ) and the Iberian lynx in Spain (Delibes-Mateos et al. 2022 ).

Economic analysis has been used to show that wildlife is an asset that, if protected, can generate substantial economic benefits for those who have the right to own or use it (Loomis 1993 , 2000 ). It is not surprising how the recreational aspects of wildlife have promoted valuation studies on mammals in temperate habitats and charismatic tropical species, with less attention to marine and aquatic species and habitats. However, numerous economic reasons exist for a more comprehensive preservation strategy, including regulating services and diverse cultural aspects, that considers habitat-wildlife interactions more broadly (de Groot et al. 2002 ; MEA 2005 ; TEEB 2010 ; UK NEA 2011 ; IPBES 2019 ). Recent studies on the ecosystem services provided by vultures show the high cost of policies failing to address the reduction of these wild birds in terms of avoided sanitary benefits due to the spread of dogs in the global south (Markandya et al. 2008 ; Margalida et al. 2010 , 2012 ), as well as the loss of regulating and supporting services such as the nutrient cycle by processing animal carcasses that if treated by current solid waste processes would contribute to generating pollution and carbon dioxide emissions (Morales-Reyes et al. 2015 ). Studies addressing the regulating services provided by vultures are so far limited to a few Asian countries and in Israel (Becker et al. 2005 , 2009 ), but their diffusion can facilitate the adoption of cost-effective conservation policies along with the implementation of more recent findings on the cultural ecosystem services provided by these wild birds whose protection can sustain the local economy of communities, such as those living in the Pyrenees (Spain), by the enhancement of avian scavenger-based tourism (Garcia-Jimenez et al. 2021 ).

Although many of the proposed studies were designed to address policies for conservation, there are examples where valuation does not result in economic preferences for conservation (e.g. van Beukering et al. 2014 ). This may happen when people are not familiar enough with ecosystems to express robust values for their protection (McMillan et al. 2006 ). Moreover, the conception of values in mainstream economic valuation is narrow, does not consider shared values (Kenter et al. 2015 ), fails to reflect the deeper meanings that places might hold (Daniel et al. 2012 ), and for many violates a sense of integrity of nature (McCauley 2006 ; O’Neill et al. 2008 ; Kronenberg 2015 ; Cooper et al. 2016 ).

Attempts to trade-off between ecological, social, and cultural dimensions of the value of nature by assuming these values are commensurable can increase conflicts rather than resolve them. Moreover, decisions based on CBA, even when based on comprehensive transaction and opportunity cost of wildlife conservation (Emerton 1999 ; Sementelli et al. 2008 ; Barua et al. 2013 ) to define value for money of policy scenarios, as for the reintroduction of species like the Eurasian lynx (White et al. 2015 ; Hawkins et al. 2020 ), can in some circumstances implicitly supports the rich and powerful, because in monetary terms they will have the largest benefits (Hockley 2014 ; Turner 2016 ). Nonetheless, understanding social perspectives on the allocation of scarce resources to conservation efforts remains important. There is substantial opportunity to consider more pluralistic values within economic valuation through DMV and better integration with non-monetary approaches. For example, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES 2019 , 2022 ), has been exploring ways to integrate the knowledge, values, and rights of local and Indigenous Peoples into conservation initiatives. The latter is an expression of a bio-cultural approach to conservation that emphasises the role of those who should be involved in the conservation process, and the need for pluralistic and partnership-based approaches to conservation (Gavin et al. 2018 ).

Deliberated preferences methodologies can support participants to think through and discuss values with each other, providing opportunities to enhance understanding of biodiversity and ecosystems through social learning. By moving from individual attitudes (Kahneman 2011 ) to preferences constructed by deliberation, as promoted by environmental psychology, human ecology, and ecological economics (Mascia et al. 2003 ; Saunders et al. 2006 ), there is potential for a more robust assessment of values for wildlife conservation.

The implementation of DMV may in fact change completely the perception of values from a finite to an inestimable asset (Kenter et al. 2011 ), limiting the use of CBA. When goods become priceless, CBA is no more of utility for decision making thus advocating the use of pluralistic and partnership-based approaches to conservation such as the Triple balance approach (Turner 2016 ). This framework suggests that only in simple and non-contested contexts, a single balance sheet consisting of a modified version of CBA is adequate. When there is increased complexity and contestation, two further sheets can be added that address social impact assessment and broader shared and cultural values. Values are aggregated and value conflicts are negotiated through deliberation. In addition, DMV studies have contributed to better exploring unrecognised preferences for wildlife conservation compared to more acknowledged projects such as renewable energy production (McMillan et al. 2006 ) and to estimating motivation for entering payment for ecosystem services schemes for the protection of nature (Lliso et al. 2020 ).

DDMV goes further as a platform to deliberate directly on the common good through discussion of social willingness to pay, providing new democratic spaces based on deliberative democracy (Irvine et al. 2016 ; Kenter 2016b ; Kenter et al. 2016a ). However, there are yet few deliberated preference studies, and a very limited number of DDMV studies informing practical conservation on the ground. Future research is necessary to demonstrate whether different DMV approaches can meet the practical demands of conservation practitioners in terms of planning, priority-setting, advocacy, and providing effective incentives. However, some of the signs are promising. While some have argued that strategies that recognize and work within the boundaries of existing values are more productive than trying to change values (Manfredo et al. 2016 , 2017 ), deliberative interventions can and do change values towards a more sustainability-aligned perspective, both at the contextual level (specific values reflecting opinions of the importance of something) and transcendental level (broad overarching guiding principles and life goals) (Kenter et al. 2011 , 2016b ; Kenter 2016c ; Raymond and Kenter 2016 ). However, whether this happens will depend on whether deliberation specifically targets transcendental values and more broadly is able to make previously implicit values explicit (Kenter et al. 2016c ).

DMV and DDMV particularly provide more of an opportunity to consider intrinsic values of nature alongside instrumental ones, but so far there has not been researched to explicitly and fully realise this, providing a potentially powerful opportunity to address an important critique in relation to economic valuation. In addition, the integration of participatory approaches may provide a more effective way to integrate values into policy and practice on the ground. As such, the future of environmental valuation may be in a closer integration between economic and broader social science approaches, which will require a loosening of some of the epistemic, ethical, value, and rationality assumptions that neoclassical environmental economists have upheld so far. However, this requires important advancement in terms of upscaling deliberative valuations, further development of best practices for deliberative interventions to support social learning and formation of shared values, and application across a more diverse range of conservation scenarios and institutional venues (e.g. payments for ecosystem services, community conservation agreements, protected areas establishment/management), and developing culturally appropriate methodological approaches for application in diverse contexts in the global south. If this can be achieved, by opening to broader perspectives of how people value and relate to nature, valuation could yet become an important bridging instrument between conserving nature for its own sake and for its important contributions to human well-being.

Data Availability

All data used were provided and made available in the manuscript. They were extracted by the bibliography and reported in all the tables included in the manuscript and in the additional references reported in the supplementary material.

For instance, some benefits provided by vulture have been quantified in biophysical terms and monetary units pointing on the capacity of these wild birds to provide regulating (avoidance of carbon emission) and cultural ecosystem services (e.g., recreation) as proposed by Garcia-Jimenez et al. ( 2021 ), Morales-Reyes et al. ( 2015 ) and Becker et al. ( 2005 ).

The initial search at the time of submission (May 2022) considered literature searches from 1990 until 2019 reflecting delay in the submission of the paper caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Under the revision if the paper, literature has been extended using the same search criteria to consider papers published until December 2022.

ABSA (2015) Game Ranching Profitability in South Africa, ABSA & Barclays

Ali AHM, Afandi SHM, Emmy PJ, Shuib A, Ramachandran S, Samdin Z (2018) Assessment of non-consumptive wildlife-oriented tourism in Sukau, Sabah using travel cost method. Int J Bus Soc 19(1):47–55

Google Scholar

Alvarez Farizo B, Hanley N, Barberán R, Lázaro A (2007) Choice modeling at the market stall: individual versus collective interest in environmental valuation. Ecol Econ 60:743–751

Article Google Scholar

Arrow K, Solow R, Portney PR, Leamer E, Radner R, Schuman H (1993) Report of the NOAA Panel on Contingent Valuation. Resources for the Future, Washington, DC, p 38

Bach L, Burton M (2017) Proximity and animal welfare in the context of tourist interactions with habituated dolphins. J Sustain Tour 25(2):181–197

Balaine L, Gallai N, Del Corso JP, Kephaliacos C (2020) Trading off environmental goods for compensations: insights from traditional and deliberative valuation methods in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Ecosyst Serv 43:101110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2020.101110

Bandara R, Tisdell C (2004) The net benefit of saving the Asian elephant: a policy and contingent valuation study. Ecol Econ 48(1):93–107

Barbier E (2000) Valuing the environment as input: applications to mangrove- fishery linkages. Ecol Econ 35:47–61

Barnes JI, Schier C, van Rooy G (1999) Tourists’ willingness to pay for wildlife viewing and wildlife conservation in Namibia. S Afr J Wildl 29(4):101–111

Bartczak A, Meyerhoff J (2013) Valuing the chances of survival of two distinct Eurasian lynx populations in Poland e Do people want to keep the doors open? J Env Manage 129:73–80

Bartkowski B, Lienhoop N, Hansjürgens B (2015) Capturing the complexity of biodiversity: a critical review of economic valuation studies of biological diversity. Ecol Econ 113:1–14

Bartkowski B, Lienhoop N (2018) Beyond rationality, towards reasonableness: enriching the theoretical foundation of deliberative monetary valuation. Ecol Econ 143:97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.07.015

Barua M, Bhagwat SA, Jadhav S (2013) The hidden dimensions of human–wildlife conflict: Health impacts, opportunity and transaction costs. Biol Conserv 157:309–316

Batel A, Basta J, Mackelworth P (2014) Valuing visitor willingness to pay for marine conservation. The case of the proposed Cres-Losinj Marine Protected Area. Croatia Ocean Coast Manag 95:72–80

Becker N, Choresh Y, Bahat O, Inbar M (2009) Economic analysis of feeding stations as a means to preserve an endangered species: the case of Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus) in Israel. J Nat Conserv 17(4):199–211

Becker N, Inbar M, Bahat O, Choresh Y, Ben-Noon G, Yaffe O (2005) Estimating the economic value of viewing griffon vultures Gyps fulvus: a Travel Cost Model Study at Gamla Nature Reserve. Israel ORYX 39(4):429–434

Bennett NJ, Roth R, Klain SC, Chan KMA, Clark DA, Cullman G, Epstein G, Nelson MP, Stedman R, Teel TL, Thomas R, Wyborn C, Curran D, Greenberg A, Sandlos J, Verıssimo D (2016) Mainstreaming the social sciences in conservation. Conserv Biol 31(1):56–66

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bennett NJ, Roth R, Klain SC, Chan K, Christie P, Clark DA, Cullman C, Curran D, Durbin TJ, Epstein G, Greenberg A, Nelson MP, Sandlos J, Stedman R, Teel TL, Thomas R, Veríssimo D, Wyborn C (2017) Conservation social science: understanding and integrating human dimensions to improve conservation. Biol Conserv 205:93–108

Bennett J, Whitten S (2003) Duck hunting and wetland conservation: compromise or synergy? Can J Agric Econ 51(2):161–173

Bergmann A, Hanley M, Wright R (2006) Valuing the attributes of renewable energy investments. Energy Policy 34(9):1004–1014

Berman M, Kofinas G (2004) Hunting for models: grounded and rational choice approaches to analysing climate effects on subsistence hunting in an Arctic community. Ecol Econ 49(1):31–46

Birol E, Karousakis K, Koundour P (2006) Using a choice experiment to account for preference heterogeneity in wetland attributes: the case of Cheimaditida wetland in Greece. Ecol Econ 60(1):145–156

Bockstael N, McConnell K (1993) Public goods as characteristic of non-market commodities. Econ J 103:1244–1257

Bond CA, Cullen KG, Larson DM (2009) Joint estimation of discount rates and willingness to pay for public goods. Ecol Econ 68(11):2751–2759

Bosetti V, Pearce D (2003) A study of environmental conflict: the economic value of Grey Seals in southwest England. Biodivers Conserv 12(12):2361–2392

Bowker JM, Newman DH, Warren RJ, Henderson DW (2003) Estimating the economic value of lethal versus nonlethal deer control in suburban communities. Soc Nat Resour 16(2):143–158

Bowles S, Gintis H (2000) Walrasian economics in retrospect. Q J Econ 115:1411–1439

Boxall PC, Macnab B (2000) Exploring the preferences of wildlife recreationists for features of boreal forest management: a choice experiment approach. Can J for Res 30(12):1931–1941

Braat LC, de Groot R (2012) The ecosystem services agenda: bridging the worlds of natural science and economics, conservation and development, and public and private policy. Ecosyst Serv 1:4–15

Brock M, Perino G, Sugden R (2017) The warden attitude: an investigation of the value of interaction with everyday wildlife. Environ Resour Econ 67(1):127–155

Bromley DW (2004) Reconsidering environmental policy: prescriptive consequentialism and volitional pragmatism. Environ Resour Econ 28:73–99

Bryce R, Irvine KN, Church A, Fish R, Ranger S, Kenter JO (2016) Subjective well-being indicators for large-scale assessment of cultural ecosystem services. Ecosyst Serv 21:258–269

Bunse L, Rendon O, Luque S (2015) What can deliberative approaches bring to the monetary valuation of ecosystem services? A literature review. Ecosyst Serv 14:88–97

Burton RJF, Schwartz G (2013) Result oriented agri-environmental scheme and their potential for promoting behavioural changes. Land Use Policy 30(1):628–641

Callaghan CT, Slater M, Major RE, Morrison M, Martin JM, Kingsford RT (2018) Travelling birds generate ecotravellers. The economic potential vagrant. Hum Dimens Wildl 23(1):71–82

Carr L, Mendelsohn R (2003) Valuing coral reefs: a travel cost analysis of the Great Barrier Reef. Ambio 32(5):353–357

Casola WR, Peterson MN, Wu Y, Sills EO, Pease BS, Pacifici K (2022) Measuring the value of public hunting land using a hedonic approach. Hum Dimens Wildl 27(4):343–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2021.1953196

Cazabon-Mannette M, Schumann P, Hailey A, Horrocks J (2017) Estimating the non-market value of sea turtle in Tobago using stated preferences techniques. J Environ Manage 192:281–291

Cerda C (2011) Willingness to pay to protect environmental services: a case study with use and non-use values in central Chile. Interciencia 36(11):796–802

Cerda C, Losada T (2013) Assessing the value of species: a case study on the willingness to pay for species protection in Chile. Environ Monit Assess 185(12):10479–10493

Chambers R (1997) Whose Reality Counts? Putting the First Last. ITDG

Chan KMA, Balvanera P, Benessaiah K, Chapman M, Díaz S, Gómez-Baggethun E, Gould R, Hannahs N, Jax K, Klain S, Luck G, Martín-López B, Muraca B, Norton B, Ott O, Pascua U, Satterfield T, Tadaki M, Taggart J, Turn N (2016) Opinion: why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. PNAS 113:1462–1465

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chan KMA, Satterfield T, Goldstein J (2012) Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecol Econ 74:8–18

Chapagain BP, Poudyal NC (2020) Economic benefit of wildlife reintroduction: a case of elk hunting in Tennessee, USA. J Environ Manage 269-110808

Child BA, Musengezi J, Parent GD, Child GFT (2012) The economics and institutional economics of wildlife on private land in Africa. Pastoralism 2:18

Chriestie M, Martin-Lopez B, Church A, Siwicka E, Szymonczyk P (2019) Understanding the diversity of values of “Nature’s contributions to people”: insights from the IPBES assessment of Europe and central Asia. Sustain Sci 14:1267–1282

Christie M, Fazey I, Cooper R, Hyde T, Kenter JO (2012) An evaluation of monetary and non-monetary techniques for assessing the importance of biodiversity and ecosystem services to people in countries with developing economies. Ecol Econ 83:69–80

Christie M, Hanley N, Warren J, Murphy K, Wright R, Hyde T (2006) Valuing the diversity of biodiversity. Ecol Econ 58:304–317

Cooper N, Brady E, Steen H, Bryce R (2016) Aesthetic and spiritual values of ecosystems: recognising the ontological and axiological plurality of cultural ecosystem “services.” Ecosyst Serv 21:218–229

Cornicelli L, Fulton DC, Grund MD, Fieberg J (2011) Hunter perceptions and acceptance of alternative deer management regulations. Wildl Soc Bull 35(3):323–329

Costanza R, de Groot R, Sutton P, van der Ploeg S, Anderson SJ, Kubiszewski I, Farber S, Turner RK (2014) Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob Environ Change 26:152–158

Curtis JA (2002) Ethics in wildlife management: What price? Environ Values 11(2):145–161

Daily GC, Ehrlich PR (1992) Population, sustainability, and Earth’s carrying capacity: A framework for estimating population sizes and lifestyles that could be sustained without undermining future generations. Bioscience 42(10):761–777

Dalerum F, Miranda M, Muniz C, Rodriguez P (2018) Effect of scarcity, aesthetics and ecology on wildlife auction prices of large African mammals. Ambio 47(1):78–85

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dalrymple CJ, Peterson MN, Cobb DT, Sills EO, Bondell HD, Dalrymple DJ (2012) Estimating Public Willingness to Fund Nongame Conservation through State Tax Initiatives. Wildl Soc Bull 36(3):483–491

Daniel TC, Muhar A, Arnberge A, Aznar O, Boyd JW, Chan K, Costanza R, Elmqvist T, Flint C, Gobste P, Grêt-Regamey A, Lave R, Muhar S, Penker M, Ribe R, Schauppenlehner T, Sikor T, Soloviy I et al (2012) Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. PNAS 109:8812–8819

Delibes-Mateos M, Glikman JA, Lafuente R, Villafuerte R, Garrido FE (2022) Support to Iberian lynx reintroduction and perceived impacts: assessments before and after reintroduction. Conserv Sci Pract 4:e605. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.605

de Groot RS, Wilson MA, Boumans RMJ (2002) A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol Econ 41:393–408

Devente J, Reed MS, Stringer LC, Valente S, Newig J (2016) How does the context and design of participatory decision making processes affect their outcomes? Evidence from sustainable land management in global drylands. Ecol Soc 21(2):24. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08053-210224

Dias V, Belcher K (2015) Value and provision of ecosystem services from prairie wetlands: a choice experiment approach. Ecosyst Serv 15:35–44

Díaz S, Pascual U, Stenseke M, Martín-López B, Watson RT, Molnár Z, Hill R, Chan KMA, Baste IA, Brauman KA, Polasky S, Church A, Lonsdale M, Larigauderie A, Leadley PW, Van Oudenhoven APE, van der Plaat F, Schröter M, Lavore S, Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y, Bukvareva E, Davies K, Demissew S, Erpul G, Failler P, Guerra CA, Hewitt CL, Keune H, Lindley S, Shirayama Y (2018) Assessing nature’s contributions to people. Science 359:270–272. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap8826

Eagle JG, Betters DR (1998) The endangered species act and economic values: a comparison of fines and contingent valuation studies. Ecol Econ 26:165–171

Emerton L (1997) The economics of tourism, and wildlife conservation in Africa. African wildlife foundation discussion papers series N.4

Emerton L (1998) Innovations for financing wildlife conservation in Kenya, presented at the 10 th Global Biodiversity forum, Bratislava

Emerton L (1999) Balancing the opportunity costs of wildlife conservation for communities around lake Mburo national park, Uganda

Emmanouilides CJ, Sgouromalli H (2013) Renewable energy sources in Crete: economic valuation results from a stated choice experiment. In 6 TH International Conference on Information And Communication Technologies In Agriculture, Food And Environment (Haicta 2013). Salampasis, M., Theodoridis, A. (Ed.) Book Series: Procedia Technology 8:406–415

Ericsson G, Kindberg J, Bostedt G (2007) Willingness to pay (WTP) for wolverine Gulo gulo conservation. Wildlife Biol 13:2–12

Everard M, Reed MS, Kenter JO (2016) The ripple effect: institutionalising pro-environmental values to shift societal norms and behaviours. Ecosyst Serv 21b:230–240

Farnsworth KD, Adenuga AH, de Groot RS (2015) The complexity of biodiversity: a biological perspective on economic valuation. Ecol Econ 120:350–354

Farnsworth KD, Lyashevska O, Fung T (2012) Functional complexity: the source of value in biodiversity. Ecol Complex 11:46–52

Farr M, Stoeckl N, Beg RA (2014) The non-consumptive (tourism) ‘value’ of marine species in the Northern section of the Great Barrier Reef. Mar Policy 43:89–103

Fischer A, Weldesemaet YT, Czajkowski M, Tadie D, Hanley N (2015) Trophy hunters’ willingness to pay for wildlife conservation and community benefits. Conserv Biol 29(4):1111–1121

Fix PJ, Manfredo MJ, Loomis JB (2005) Assessing validity of elk and deer license sales estimated by contingent valuation. Wildl Soc Bull 33(2):633–642

Forster J (ed) (1997) Valuing Nature? Routledge, New York

Frew KN, Peterson MN, Sills E, Moorman CE, Bondel H, Fueller JC, Howell DL (2018) Market and nonmarket valuation of North Carolina’s Tundra swans among hunters, wildlife watchers and the public. Wildl Soc Bull 42(3):478–487

Fried BM, Adams RM, Berrens RP, Bergland O (1995) Willingness to pay for a change in elk hunting quality. Wildl Soc Bull 23(4):680–686

Frontuto V, Dalmazzone S, Vallino E, Giaccaria S (2017) Earnmarking conservation: further inquiry on scope effects in stated preference method applied to nature-based tourism. Tour Manag 60:130–139

Gan F, Du H, Wei Q, Fan E (2011) Evaluation of the ecosystem values of aquatic wildlife reserves: a case of Chinese Sturgeon Natural Reserve in Yichang reaches of the Yangtzeriver. J Appl Ichthyol 27(2):376–382

Garrod GD, Willis KG (1994) Valuing biodiversity and nature conservation at a local-level. Biodivers Conserv 3(6):555–565

Garcia-Jimenez R, Morales-Reyes Z, Perez-Garcia JM, Margalida A (2021) Economic valuation of non-material contributions to people provided by avian scavengers: Harmonizing conservation and wildlife-based tourism. Ecol Econ 187:107088

Gascoigne W, Hill R, Haefele M, Loomis J, Hyberg S (2021) Economics of the Conservation Reserve Program and the wildlife it supports: a case study of upland birds in South Dakota. J Outdoor Recreat Tour 35:100385

Gavin MC, McCarte J, Berkes F, Mead ATP, Sterling EJ, Tang R, Turner NJ (2018) Effective biodiversity conservation requires dynamic, pluralistic, partnership-based approaches. Sustainability 10:1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061846

Getzner M (2015) Importance of Free-Flowing Rivers for Recreation: Case Study of the River Mur in Styria, Austria. J Water Resour Plan Manag141(2): pages not reported. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000442

Gómez-Baggethun E, Ruiz-Pérez M (2011) Economic valuation and the commodification of ecosystem services. Prog Phys Geogr 35:613–628

Gren IM, Haggmark-Svensonn T, Elofsson K, Engelmann M (2018) Economics of wildlife management. An Aoverview Eur J Wildl Res 64:22

Guimaraes MH, Nunes LC, Madureira L, Santos JL, Bosk T, Dentinho T (2015) Measuring birdwatchers preferences: a case for using online networks and mixed-mode surveys. Tour Manage 46:102–113

Han SY, Lee CK (2008) Estimating the value of preserving the Manchurian black bear using the contingent valuation method. Scand J for Res 23(5):458–465

Hanemann M (1994) Valuing the Environment through Contingent Valuation. JEP 8(4):19–43

Hanley N, Czajkowski M, Hanley-Nickolls R, Redpath S (2010) Economic values of species management options in human-wildlife conflicts Hen Harriers in Scotland. Ecol Econ 70(1):107–113

Hanley N, MacMillan D, Patterson I, Wright RE (2003) Economics and the design of nature conservation policy: a case study of wild goose conservation in Scotland using choice experiments. Anim Conserv 6:123–129

Hanley N, Hynes S, Patterson D, Jobstvogt N (2015) Economic Valuation of Marine and Coastal Ecosystems: is it currently fit for purpose? J Ocean Coast Econ 2(1):1–24

Harihar A, Verissimo D, MacMillan DC (2015) Beyond compensation: integrating local communities’ livelihood choices in large carnivore conservation. Global Environ Change 33:122–130

Hattam C, Böhnke-Henrichs A, Börger T, Burdon D, Hadjimichael M, Delaney A, Atkins JP, Garrard S, Austen MC (2015) Integrating methods for ecosystem service assessment and valuation: mixed methods or mixed messages? Ecol Econ 120:126–138

Hockley N (2014) Cost-benefit analysis: a decision-support tool or a venue for contesting ecosystem knowledge? Environ Plan C: Politics Space 32:283–300

Horne P, Petajisto L (2003) Preferences for alternative moose management regimes among Finnish landowners: a choice experiment approach. Land Econ 79(4):472–482

Howarth RB, Wilson MA (2006) A Theoretical Approach to Deliberative Valuation: Aggregation by Mutual Consent. Land Econ 82:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.82.1.1

Hawkins SA, Vangerschov Iversen S, Brady B, Mayhew M, Smith D, Lipscombe S, White C, Eagle A, Convery I (2020) Community perspectives on the reintroduction of Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) to the UK. Restor Ecol 28(6):1408–1418

Hutt CP, Hunt KM, Schlechte JW, Buckmeier DL (2013) Effects of catfish angler catch-related attitudes on fishing trip preferences. N Am J Fish Manag 33(5):965–976

Imamura K, Takano KT, Mori N, Nakashizuka T, Managi S (2016) Attitudes toward disaster-prevention risk in Japanese coastal areas: analysis of civil preference. Nat Hazards 82(1):209–226

IPBES (2019) Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science - Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, and H. T. Ngo (editors). IPBES Secretariat, Bonn, Germany

IPBES (2022) Summary for policymakers of the methodological assessment regarding the diverse conceptualization of multiple values of nature and its benefits, including biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services (assessment of the diverse values and valuation of nature) - Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES Secretariat, Bonn, Germany

Irvine KN, O’Brien L, Ravenscroft N, Cooper N, Everard M, Fazey I, Reed MS, Kenter JO (2016) Ecosystem services and the idea of shared values. Ecosyst Serv 21:184–193

Isacs L, Kenter J, Wetterstrand H, Katzeff C (2021) What does value pluralism mean in practice? An empirical demonstration from a deliberative valuation. People and Nature. In press

Jacobs S, Dendoncker N, Martín-López B, Barton DN, Gomez-Baggethun E, Boeraeve F, McGrath FL, Vierikko K, Geneletti D, Sevecke KJ, Pipart N, Primmer E, Mederly P, Schmidt S, Aragão A, Baral H, Bark RH, BricenoT BD et al (2016) A new valuation school: integrating diverse values of nature in resource and land use decisions. Ecosyst Serv 22:213–220