- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Wicked Problems

What are wicked problems.

Wicked problems are problems with many interdependent factors making them seem impossible to solve. Because the factors are often incomplete, in flux, and difficult to define, solving wicked problems requires a deep understanding of the stakeholders involved, and an innovative approach provided by design thinking. Complex issues such as healthcare and education are examples of wicked problems.

- Transcript loading…

The term “wicked problem” was first coined by Horst Rittel, design theorist and professor of design methodology at the Ulm School of Design, Germany. In the paper “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” he describes ten characteristics of wicked problems:

There is no definitive formula for a wicked problem.

Wicked problems have no stopping rule, as in there’s no way to know your solution is final.

Solutions to wicked problems are not true-or-false; they can only be good-or-bad.

There is no immediate test of a solution to a wicked problem.

Every solution to a wicked problem is a "one-shot operation"; because there is no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error, every attempt counts significantly.

Wicked problems do not have a set number of potential solutions.

Every wicked problem is essentially unique.

Every wicked problem can be considered a symptom of another problem.

There is always more than one explanation for a wicked problem because the explanations vary greatly depending on the individual perspective.

Planners/designers have no right to be wrong and must be fully responsible for their actions.

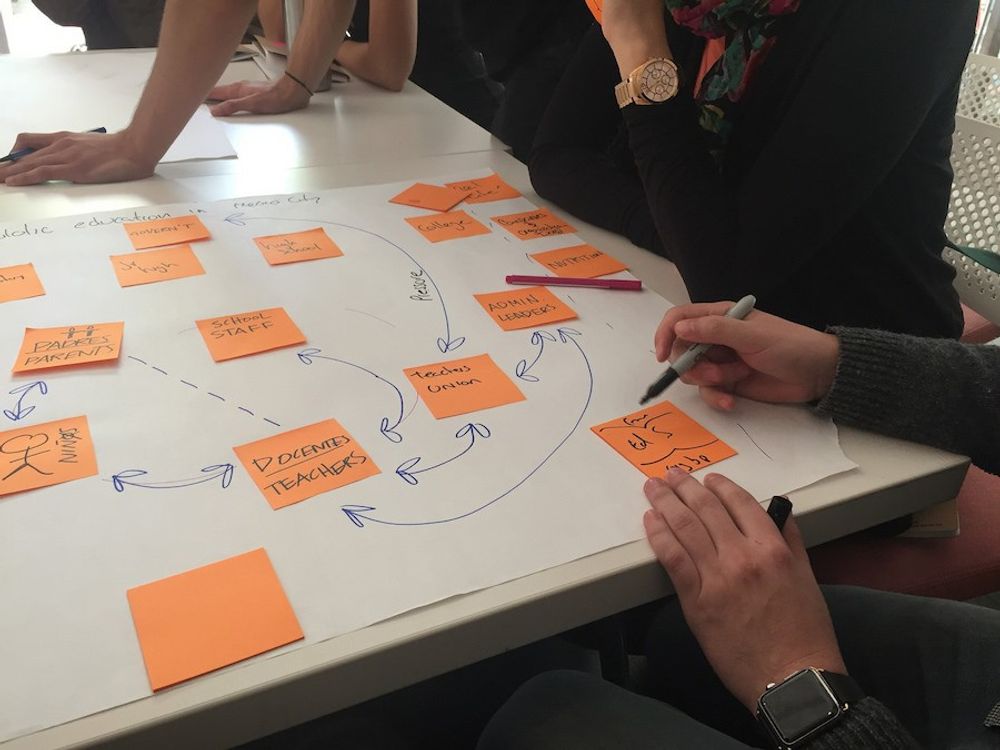

Design theorist and academic Richard Buchanan connected design thinking to wicked problems in his 1992 paper “Wicked Problems in Design Thinking.” Design thinking’s iterative process is extremely useful in tackling ill-defined or unknown problems—reframing the problem in human-centric ways, creating many ideas in brainstorming sessions, and adopting a hands-on approach in prototyping and testing.

Questions related to Wicked Problems

Yes, poverty is a wicked problem.

As Don Norman elucidates in this video , wicked problems refer to challenges that are hard to define and address due to their complex nature, much like complex socio-technical systems. Like the example of world peace Norman mentions, poverty possesses multifaceted roots and impacts, making solutions elusive. Tackling such issues doesn't guarantee permanent resolution. However, it's crucial to understand that even if we can't wholly eradicate problems like poverty, continuously striving for improvements and bettering lives is the way forward. While wicked problems persist, consistent advancement in addressing them represents success.

Indeed, climate change exemplifies a wicked problem. As Don Norman elucidates in this video, the complexities of climate systems, human activity, ecology, and their interconnectedness pose challenges in understanding and addressing the issue.

The non-linear nature of these systems, intertwined with feedback loops and feed-forward loops, adds to the intricacy. Moreover, people's simplistic causality models hinder recognizing multifaceted causes and delayed consequences. While many often resist change, especially those benefiting from the status quo, the palpable effects of climate change—fires, floods, famine, and extreme weather events—are now evident worldwide. Although historically, we've been reactive, responding post-calamity, the tangible repercussions of climate change have catalyzed a global response, providing a glimmer of optimism for the future.

Yes, healthcare is a wicked problem. Addressing healthcare issues often involves navigating complex, interconnected systems that require multi-faceted approaches. In Don Norman's video, he speaks about incrementalism, where tackling significant challenges is done step by step.

Incrementalism : Address healthcare challenges in small, adaptable steps, ensuring each move is in the right direction.

Minimum Viable Project (MVP) : Borrowed from Agile programming, it's about creating small, functional segments of the larger solution. This method ensures that each part, even if small, is working effectively.

Object-Oriented Approach : Here, the focus is on the inputs and outputs of a system, not the internal process. This modular design allows for flexibility and adaptation as healthcare needs and methods evolve.

According to HCI expert Alan Dix, understanding the difference between puzzles and real-world problems is crucial. Puzzles have a single correct solution with all the necessary information provided. However, wicked problems inherent to real-world scenarios are not as clearly defined as puzzles. They may not have a definite answer and may even be insoluble in their initial form. The primary step is deeply understanding the problem, as solutions may become evident once fully grasped. Indeed, there's a saying, "If I had an hour to solve a problem, I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions." Thus, investing time in understanding, redefining, and negotiating the problem can pave the way to practical solutions. In the realm of wicked problems, creative thinking and individualized approaches are paramount.

In design thinking, wicked problems refer to complex challenges that lack clear solutions or boundaries. Unlike puzzles, which have a definitive answer, wicked problems are unique, possess no classic formulation, and their potential solutions are non-enumerable. The complexity arises from the interconnectedness of factors and the inability to use a prior solution for a new problem. These problems often require creative, individualized approaches and deep understanding for effective resolution. As detailed in this article on the history of Design Thinking on interaction-design.org, design thinking as a methodology emphasizes empathy, iteration, and collaboration, making it aptly suited to address wicked problems by redefining and understanding them from various perspectives.

Climate Change : Addressing the causes and impacts of global warming involves balancing the needs of various nations, industries, and populations. Solutions can have unintended consequences, and only some answers satisfy all stakeholders.

Healthcare : Ensuring affordable, high-quality healthcare for all is a complex issue with economics, politics, and individual health needs.

Poverty and Economic Inequality : Addressing the root causes and alleviating the effects of poverty require multifaceted solutions involving education, job creation, health services, and more.

Urban Planning and Housing : Balancing the needs for housing, transportation, green spaces, and commercial areas in rapidly growing urban areas is a constantly evolving challenge.

Global Terrorism : Addressing the root causes and responding to the effects of terrorism involves considerations of international relations, religion, socio-economic factors, and security concerns.

Water Scarcity : Ensuring adequate, clean water for all involves a mix of technological, environmental, political, and social solutions.

Food Security : Ensuring everyone has access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food involves considerations of agriculture, trade policies, climate change, and socio-economic disparities.

Immigration and Refugees : Managing migration and addressing the needs of refugees requires balancing national security, economic interests, humanitarian concerns, and social integration.

Education Reform : Ensuring quality education for all, adapting to technological changes, and preparing students for a rapidly changing world is a multifaceted challenge.

Biodiversity Loss : Protecting endangered species and habitats in the face of urban development, climate change, and other pressures is a complex, ongoing struggle.

These are just a few examples, and many other problems could qualify as "wicked" given the proper context and scale. The hallmark of wicked problems is that they can't be solved with linear, traditional problem-solving methods and require a more holistic, adaptive, and iterative approach.

Wicked problem in leadership refers to challenges that leaders face, which are complex, multifaceted, and often resist straightforward solutions. These problems often arise from various factors, including human behavior, organizational dynamics, external pressures, and evolving circumstances. Addressing such issues requires a leader to navigate ambiguity, adapt to changing contexts, and collaborate with diverse stakeholders. Here are some examples of wicked problems specific to leadership:

Organizational Culture Change : Changing the ingrained culture of an organization is a long-term process filled with resistance, unexpected challenges, and the need for continuous adaptation. A leader might have a vision for a more innovative or inclusive culture, but translating that vision into tangible changes in behavior, systems, and practices is a wicked problem.

Digital Transformation : In an era of rapid technological change, leaders face the wicked problem of ensuring their organizations adapt and innovate while maintaining core functions and managing potential disruptions.

Ethical Dilemmas : Leaders sometimes face decisions without clear, correct answers, and various ethical principles might conflict. These dilemmas involve privacy, data security, team member rights, or corporate social responsibility.

Stakeholder Management : Leaders in complex organizations must manage a web of stakeholders, each with distinct interests, priorities, and expectations. Balancing the needs of employees, shareholders, customers, regulators, and the broader community is a constant challenge.

Crisis Management : Responding to unforeseen crises, be they financial, reputational, or operational, requires leaders to make quick decisions with limited information, all while managing internal and external perceptions.

Wicked problems are complex challenges that defy straightforward solutions. While they are inherently complex and can be perceived as 'bad' due to their complexity and often represent negative scenarios, they also present opportunities for innovation and deep understanding. Addressing wicked problems often requires a blend of systems thinking and agile approaches. This article on Interaction Design Foundation delves into a 5-step method to tackle wicked problems, combining systems thinking with agile methodology. Therefore, while wicked problems are challenging, they can lead to significant growth and insights when approached effectively.

Want to explore wicked problems further? Dive into our 21st Century Design course to uncover modern design challenges and solutions. For a deep dive into design's impact on global issues, explore Design for a Better World . Both courses empower you with tools to navigate wicked problems in design.

Answer a Short Quiz to Earn a Gift

What defines a wicked problem?

- A complex problem with a clear and permanent solution.

- A problem with complex, interdependent factors that make it seem impossible to solve.

- A simple and straightforward problem with multiple intricate solutions.

Why is each wicked problem unique?

- Because they are easy to solve with traditional methods.

- Because they are identical to other problems.

- Because they present unique circumstances and challenges.

What kind of solutions do wicked problems typically have?

- Solutions that are binary.

- Solutions that are good or bad.

- Solutions that are simple or complex.

What is expected of designers when dealing with wicked problems?

- They can rely on trial and error without consequences.

- They have the right to be wrong.

- They must be fully responsible for their actions.

Why are wicked problems potentially symptoms of other problems?

- Because they are often symptoms of deeper, interconnected issues.

- Because they exist in isolation.

- Because they have straightforward causes and effects.

Better luck next time!

Do you want to improve your UX / UI Design skills? Join us now

Congratulations! You did amazing

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

Check Your Inbox

We’ve emailed your gift to [email protected] .

Literature on Wicked Problems

Here’s the entire UX literature on Wicked Problems by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Wicked Problems

Take a deep dive into Wicked Problems with our course Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide .

Some of the world’s leading brands, such as Apple, Google, Samsung, and General Electric, have rapidly adopted the design thinking approach, and design thinking is being taught at leading universities around the world, including Stanford d.school, Harvard, and MIT. What is design thinking, and why is it so popular and effective?

Design Thinking is not exclusive to designers —all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering and business have practiced it. So, why call it Design Thinking? Well, that’s because design work processes help us systematically extract, teach, learn and apply human-centered techniques to solve problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, businesses, countries and lives. And that’s what makes it so special.

The overall goal of this design thinking course is to help you design better products, services, processes, strategies, spaces, architecture, and experiences. Design thinking helps you and your team develop practical and innovative solutions for your problems. It is a human-focused , prototype-driven , innovative design process . Through this course, you will develop a solid understanding of the fundamental phases and methods in design thinking, and you will learn how to implement your newfound knowledge in your professional work life. We will give you lots of examples; we will go into case studies, videos, and other useful material, all of which will help you dive further into design thinking. In fact, this course also includes exclusive video content that we've produced in partnership with design leaders like Alan Dix, William Hudson and Frank Spillers!

This course contains a series of practical exercises that build on one another to create a complete design thinking project. The exercises are optional, but you’ll get invaluable hands-on experience with the methods you encounter in this course if you complete them, because they will teach you to take your first steps as a design thinking practitioner. What’s equally important is you can use your work as a case study for your portfolio to showcase your abilities to future employers! A portfolio is essential if you want to step into or move ahead in a career in the world of human-centered design.

Design thinking methods and strategies belong at every level of the design process . However, design thinking is not an exclusive property of designers—all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering, and business have practiced it. What’s special about design thinking is that designers and designers’ work processes can help us systematically extract, teach, learn, and apply these human-centered techniques in solving problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, in our businesses, in our countries, and in our lives.

That means that design thinking is not only for designers but also for creative employees , freelancers , and business leaders . It’s for anyone who seeks to infuse an approach to innovation that is powerful, effective and broadly accessible, one that can be integrated into every level of an organization, product, or service so as to drive new alternatives for businesses and society.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you complete the course. You can highlight them on your resume, CV, LinkedIn profile or your website .

All open-source articles on Wicked Problems

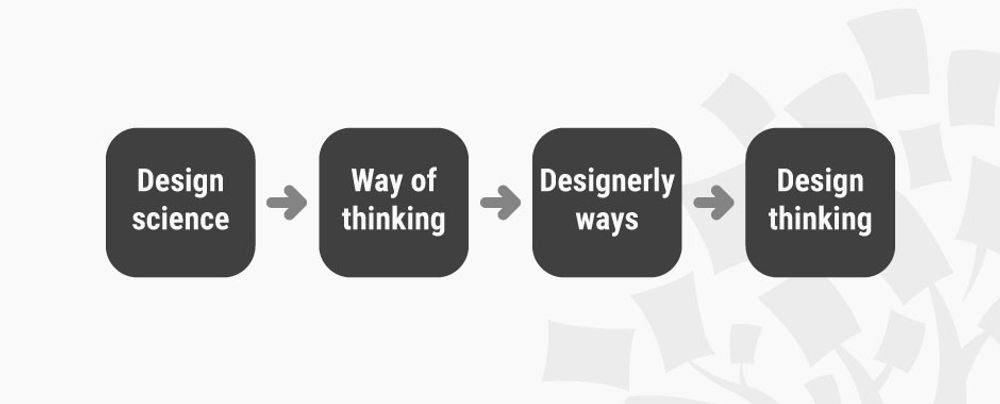

The history of design thinking.

- 1.1k shares

- 2 years ago

What Are Wicked Problems and How Might We Solve Them?

- 10 mths ago

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

Register your interest for the September session now and enjoy exclusive savings!

Certification

Pathway to expertise: Unveiling the system thinking certification journey.

CSTA | CSTP | CSTT | CSTC

MICRO CREDENTIALS

Modular Learning

Upskill and earn systems thinking micro-credentials incrementally to advance your career.

Ready to level up your experience and unlock new possibilities? Explore our public training calendar.

- Digital Badge

Make a powerful impression and showcase your accomplishment on your favourite social media platforms.

Business Solutions

Transform your business using systems thinking and let us guide you on this exciting journey.

- Training Partner

Explore our training partner program for in-house rollout: develop, upskill, and empower your team through systems thinking.

Systems Leadership

Elevate your teams's leadership skills - Discover our Systems Leadership training program.

- Request a Private Class

Invest in your team's growth and enhance problem-solving abilities that drive innovation.

Unleash the power systems thinking with our captivating blogs.

- News & Press

Read the latest news and updates about Systems Thinking Alliance.

Learn clear and concise explanations of essential system thinking terminologies.

Newsletter Archive

Access past editions of our insightful Systems Thinking newsletters here.

Brand and Guidelines

Discover how we enrich our brand through the implementation of inspiring design guidelines.

About Alliance

Our mission is to help individuals and organizations make transformative changes by embracing systems thinking.

Need assistance or have a query? Reach out to us, we're here to help!

Digital Badge Program

Elevate your teams’s leadership skills – Discover our Systems Leadership training program.

Invest in your team’s growth and enhance problem-solving abilities that drive innovation.

News & Press

Need assistance or have a query? Reach out to us, we’re here to help!

UNRAVELING COMPLEXITY

The ten key properties that define wicked problems

- July 13, 2024

- 5 Minutes Read

wicked problems

"A great many barriers keep us from perfecting such a planning/governing system. Theory is inadequate for decent forecasting, our intelligence is insufficient to our tasks, plurality of objectives held by pluralities of politics makes it impossible to pursue unitary aims, and so on. The difficulties attached to rationality are tenacious, and we have so far been unable to get untangled from their web. This is partly because the classical paradigm of science and engineering - the paradigm that has underlain modern professionalism - is not applicable to the problems of open societal systems." Rittel & Webber, 1973

- There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem

- Wicked problems have no stopping rule

- Solutions to wicked problems are not true-or-false, but good-or-bad

- There is no immediate and no ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem.

- Every solution to a wicked problem is a “one-shot operation”; because there is no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error, every attempt counts significantly

- Wicked problems lack a finite set of potential solutions and do not have a clearly defined set of allowable actions for planning.

- Every wicked problem is essentially unique.

- Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem.

- The existence of a discrepancy representing a wicked problem can be explained in numerous ways. The choice of explanation determines the nature of the problem’s

The term “wicked problem” was introduced in 1973 by social planners Horst W.J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber in their seminal paper titled “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” published in Policy Sciences. The concept arose from their observation that traditional approaches to problem-solving and planning were inadequate for addressing the complexity and interconnectedness of certain social issues.

In a world increasingly dominated by complex societal challenges, the concept of “wicked problems” emerges as a critical concern for planners, policymakers, and social professionals. These problems evade simple solutions due to numerous barriers, such as inadequate theories for prediction, insufficient intelligence for implementation, and the impossibility of achieving singular objectives within diverse political landscapes.

Rational approaches often fall short when addressing wicked problems because traditional science and engineering paradigms do not apply to open societal systems. Social professions have mistakenly adopted these paradigms, leading to dissatisfaction among lay customers who feel their issues remain unresolved despite professional intervention. This misconception arises from the erroneous belief that societal issues can be approached in the same manner as scientific or engineering problems.

Wicked problems are inherently different. They are ill-defined, rely on elusive political judgment rather than definitive solutions, and encompass issues such as public policy decisions on freeway locations, tax rate adjustments, school curriculum modifications, and crime confrontations. Unlike “tame” problems, which have clear missions and solutions, wicked problems are complicated by their moral implications and inherent complexity.

Addressing these wicked problems requires a nuanced understanding and approach that transcends traditional scientific and engineering frameworks. Recognizing their unique properties is the first step toward developing more effective strategies to navigate their intricate challenges.

1. There is no definitive formulation of a wicked problem

Wicked problems are so complex and intertwined with various factors that you cannot fully understand or define them in a fixed, complete manner. Unlike simpler, “tame” problems that can be clearly outlined and solved with a straightforward process, wicked problems evolve and change as you work on them.

To fully grasp a wicked problem, one must anticipate a comprehensive array of potential solutions. For instance, addressing poverty involves considering various factors such as low income, economic deficiencies, lack of skills, education, health issues, and cultural aspects. Defining the problem necessitates identifying its root causes, which simultaneously suggests potential solutions.

Formulating a wicked problem is essentially equivalent to finding a solution. The specification of the problem directs the approach to its treatment, and recognizing aspects of the problem inherently implies corresponding solutions. Traditional problem-solving phases—understanding, gathering information, analyzing, synthesizing, and solving—do not apply to wicked problems. Instead, these issues require a holistic understanding of both the context and potential solution concepts.

Problems and solutions for wicked issues gradually emerge through critical argument and judgment among participants. Optimization models, which typically require defining the solution space, constraints, and performance measures, underscore the wicked nature of the problem. Defining these elements is often more crucial than finding an optimal solution within the established constraints.

2. Wicked problems have no stopping rule

Wicked problems are distinct because they have no stopping rule. Unlike solving a chess problem or a mathematical equation, where clear criteria signal when a solution has been found, wicked problems lack such definitive markers. When dealing with planning problems, the act of solving them is intertwined with understanding their nature. Since there are no set criteria for sufficient understanding and no definitive end to the causal chains connecting various open systems, planners can always strive for a better solution. The decision to stop working on a wicked problem is not dictated by the problem itself but by external factors such as time, money, or patience. Ultimately, the planner might conclude with statements like ‘That’s good enough,’ ‘This is the best I can do within the limits,’ or ‘I am satisfied with this solution,’ indicating that the resolution is more about reaching a practical endpoint than achieving an absolute one.

3. Solutions to wicked problems are not true-or-false, but good-or-bad

When solving equations or determining the structural formula of a chemical compound, there are well-established criteria to objectively decide if the solution is correct or incorrect. These criteria can be independently verified by other experts familiar with them, resulting in clear and unambiguous answers.

However, when it comes to wicked problems, there are no straightforward true or false answers. Typically, multiple stakeholders are involved, each with their own perspective, interests, and values. None of these parties has the authority to set definitive rules for determining the correctness of a solution. Consequently, their evaluations of proposed solutions vary widely, influenced by their group affiliations, personal interests, and ideological beliefs. These judgments are often expressed in subjective terms such as “good,” “bad,” “better,” “worse,” “satisfying,” or “good enough.”

4. There is no immediate and no ultimate test of a solution to a wicked problem.

When solving tame problems, it’s relatively straightforward to assess how effective a solution is. Typically, the evaluation is controlled by a small group of people who are directly involved and interested in the problem.

However, tackling wicked problems is a different story. Once a solution is implemented, it can lead to a series of consequences that unfold over an extended, and often unpredictable, period. The ripple effects may bring about unforeseen issues that overshadow the initial benefits. In extreme cases, the situation could end up worse than it was before the solution was applied.

The challenge with wicked problems is that we can’t fully understand the impact of our actions until all the repercussions have played out. Predicting every possible outcome through all affected lives in advance or within a short timeframe is simply impossible.

Understanding these complexities is crucial for anyone looking to address significant societal, environmental, or organizational issues. It reminds us that while some problems have clear-cut solutions, others require careful consideration of long-term consequences and continuous adaptation.

5. Every solution to a wicked problem is a “one-shot operation”; because there is no opportunity to learn by trial-and-error, every attempt counts significantly

The Challenges of Tackling Wicked Planning Problems in fields such as science, mathematics, chess, puzzle-solving, or mechanical engineering design, problem solvers have the luxury of experimenting without dire consequences. They can test various approaches without worrying about significant repercussions. For instance, losing a chess game doesn’t typically affect other games or impact non-players.

However, dealing with wicked problems is a different story. Every solution implemented in these scenarios has lasting effects that can’t simply be undone. Unlike a chess game, you can’t just build a freeway, assess its performance, and then easily make corrections if it doesn’t meet expectations. Large public works projects are practically irreversible, and their outcomes often have long-lasting impacts. Many people’s lives may be irreversibly affected, and substantial amounts of money will have been spent—another irreversible commitment.

This principle applies to most large-scale public works and virtually all public service programs. For example, the effects of an experimental curriculum will influence students well into their adult lives.

Whenever actions are essentially irreversible and the consequences have long-lasting effects, every decision matters. Any attempt to reverse a decision or correct undesirable outcomes introduces another set of wicked problems, which come with their own set of dilemmas.

In summary, the complexity and irreversibility of wicked planning problems require careful consideration of each solution, as the impact of these decisions extends far beyond the immediate future.

6. Wicked problems lack a finite set of potential solutions and do not have a clearly defined set of allowable actions for planning.

Wicked problems are messy and complex, making it hard to identify or even prove that all possible solutions have been considered. Sometimes, no solution is found due to conflicting aspects of the problem. For instance, a problem might require two opposite outcomes at the same time. Or, the issue might simply be that the problem-solver hasn’t come up with a viable solution—though someone else might.

When dealing with wicked problems, especially in social policy, numerous potential solutions might arise, while many others remain unthought-of. It takes sound judgment to decide whether to explore more solutions and which ones to implement.

In games like chess and fields like mathematics and chemistry, the rules and operations are clear and finite, covering all possible scenarios. However, this clarity doesn’t exist in social policy. Take crime reduction strategies, for example. There are no fixed rules on what approaches are acceptable. New ideas can always become serious candidates for solving problems like street crime.

Some proposed methods might include disarming the police, as done in England, to make criminals less likely to use firearms. Others suggest changing laws that define crime, such as legalizing marijuana or decriminalizing car theft, effectively reducing crime by altering definitions. Moral rearmament, focusing on ethical self-control instead of enforcement by police and courts, is another idea. Extreme solutions, like executing all criminals or giving free loot to potential thieves to remove their incentive, also come up.

In areas with poorly defined problems and solutions, feasible plans depend on practical judgment, the ability to evaluate unconventional ideas, and the trust between planners and their audience that leads to an agreement on trying new approaches.

7. Every wicked problem is essentially unique.

Wicked problems are complex and unique issues that can’t be solved with a one-size-fits-all approach. Unlike tame problems in mathematics, which can be classified and solved using a set of standard techniques, wicked problems lack such clear-cut solutions.

Each wicked problem has its own peculiarities that make it distinct. Even if two problems share many similarities, there’s always a chance that a significant difference exists, which makes finding a solution more challenging. For instance, while building a subway system in one city might seem similar to another, differences in commuter habits and residential patterns can drastically alter the approach needed.

In the realm of social policy planning, this complexity is even more pronounced. Each situation is unique, and applying solutions from physical science and engineering directly to social issues can be counterproductive, or even harmful. Understanding the unique characteristics of each problem is crucial for effective planning and problem-solving.

Therefore, when tackling wicked problems, it’s essential to remain flexible and open-minded, avoiding premature conclusions about which solutions to apply. Recognizing the uniqueness of each situation ensures that solutions are tailored, context-specific, and ultimately more effective.

Transform Your Thinking

Join our Systems Thinking certification to unlock innovative solutions for complex challenges.

8. Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem.

Wicked problems are tricky issues that often point to other underlying problems. They can be seen as gaps between “what is” and “what should be.” Solving a wicked problem starts with figuring out what’s causing the gap. But fixing that cause tends to reveal another problem, making the original issue just a symptom of something bigger.

For instance, “crime in the streets” might be seen as a result of moral decay, permissiveness, lack of opportunity, wealth, poverty, or whatever explanation you prefer. The level at which we address a problem often depends more on the analyst’s confidence than on any logical basis. There’s no “natural” level for tackling a wicked problem. The higher the level, the broader and more general the problem becomes, making it harder to solve. However, addressing only the symptoms isn’t effective, so it’s best to aim for the highest level possible to find a solution.

Incrementalism, or taking small steps to improve things, also has its pitfalls. Tackling a problem at too low a level might make the higher-level issues even harder to address. For example, focusing on reducing healthcare wait times by adding more chairs in the waiting room or streamlining the check-in process might provide short-term relief. However, these measures could make it more challenging to implement necessary structural changes, as they don’t address underlying issues like staff shortages or outdated technology. As a result, those improvements may lock in existing inefficiencies and increase the cost of comprehensive reform. Additionally, stakeholders who benefit from the incremental changes might resist future efforts to overhaul the system.

In organizations, it’s common for members to see problems at a level just below their own. For example, if you ask a hospital administrator about the challenges their hospital faces, they might highlight the need for better medical equipment rather than tackling broader issues such as inadequate staffing levels or inefficient healthcare policies.

9. The existence of a discrepancy representing a wicked problem can be explained in numerous ways. The choice of explanation determines the nature of the problem’s resolution

The process of defining and explaining a wicked problem is crucial because it shapes how we attempt to resolve it. Different perspectives lead to different approaches, each with its own set of potential outcomes and challenges. Crime in the streets can be attributed to various factors such as:

- Insufficient police presence

- High number of criminals

- Inadequate laws

- Excessive policing

- Cultural deprivation

- Lack of opportunities

- Abundance of guns

- Biological factors

Each factor suggests a different approach to tackling crime. But which one is correct? Unfortunately, there’s no clear way to determine the right answer. Wicked problems, like crime, have more ways to refute a hypothesis than in traditional sciences.

In science, the process is straightforward. In dealing with wicked problems, arguments are richer and more varied than in scientific discourse. Due to the unique nature of each problem and lack of rigorous experimentation, it’s hard to definitively test any hypothesis.

Ultimately, the choice of explanation is subjective and influenced by personal beliefs. People choose explanations that seem most plausible to them and align with their intentions and available actions. The analyst’s “world view” is the strongest determining factor in explaining a discrepancy and, therefore, in resolving a wicked problem

10. The planner has no right to be wrong.

In scientific research, the principle of proposing solutions as hypotheses to be refuted is fundamental. This approach, as Karl Popper describes in “The Logic of Scientific Discovery,” means that scientists are not blamed for suggesting hypotheses that are later disproven. They are simply contributing to the ongoing quest for knowledge.

However, this principle does not apply to the world of planning, especially when dealing with complex, “wicked” problems. Unlike scientific hypotheses, planners’ decisions have immediate and significant impacts on people’s lives. Thus, the stakes are much higher.

Wicked problems are inherently difficult to define and solve because they are entangled in complex causal webs and varying public opinions. For example, urban planners may struggle to address issues like traffic congestion or affordable housing, as these problems involve numerous variables and stakeholders with conflicting interests.

Ultimately, planners must navigate these ambiguities and conflicting values without the luxury of being wrong. Their responsibility is to make decisions that improve the world we live in, even when those decisions are fraught with uncertainty.

Understanding the ten properties of wicked problems is crucial for anyone involved in tackling complex societal challenges. These properties highlight that there are no one-size-fits-all solutions and that every wicked problem requires a unique approach. By acknowledging the inherent complexity and interconnected nature of these issues, we can better prepare to navigate the uncertainties and contradictions they present. As we continue to grapple with the multifaceted problems of our time, embracing the principles outlined by Rittel and Webber can guide us toward better strategies, ultimately leading to more effective and sustainable outcomes.

References :

- Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

- Complexity , decision making , planner , proposed solutions , Wicked Problem

Trending Articles

Recognizing when to apply systems thinking

In today’s fast-paced and ever-evolving world, navigating complexities has become an essential skill for leaders, innovators, and problem-solvers. One powerful

Russell Ackoff: A Visionary in Systems Thinking

In the realm of management and organizational studies, few names carry the weight and respect of Russell Ackoff. Widely known

Donella Meadows’ Pioneering Contributions to Systems Thinking and Environmental Advocacy

In a world that is increasingly recognizing the inextricable link between our actions and the global ecosystem, the legacy of

PO Box 40033 Derry Heights Milton, ON L9T 7W4 Canada

Individuals

- Certifications

- Micro-Credentials

- Training Calendar

- Business Solution

- System Leadership

- Code of Ethics

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

🍪 Our website uses cookies

Our website use cookies. By continuing, we assume your permission to deploy cookies as detailed in our Privacy Policy.

- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

Wicked Problems: Problems Worth Solving

The following is an excerpt from the book.

- order reprints

- related stories

By Jon Kolko Mar. 6, 2012

171 pages, Austin Center for Design, 2012

Buy the book »

A wicked problem is a social or cultural problem that is difficult or impossible to solve for as many as four reasons: incomplete or contradictory knowledge, the number of people and opinions involved, the large economic burden, and the interconnected nature of these problems with other problems. Poverty is linked with education, nutrition with poverty, the economy with nutrition, and so on. These problems are typically offloaded to policy makers, or are written off as being too cumbersome to handle en masse. Yet these are the problems—poverty, sustainability, equality, and health and wellness—that plague our cities and our world and that touch each and every one of us. These problems can be mitigated through the process of design, which is an intellectual approach that emphasizes empathy, abductive reasoning, and rapid prototyping.

Horst Rittel, one of the first to formalize a theory of wicked problems, cites ten characteristics of these complicated social issues:

- Wicked problems have no definitive formulation. The problem of poverty in Texas is grossly similar but discretely different from poverty in Nairobi, so no practical characteristics describe “poverty.”

- It’s hard, maybe impossible, to measure or claim success with wicked problems because they bleed into one another, unlike the boundaries of traditional design problems that can be articulated or defined.

- Solutions to wicked problems can be only good or bad, not true or false. There is no idealized end state to arrive at, and so approaches to wicked problems should be tractable ways to improve a situation rather than solve it.

- There is no template to follow when tackling a wicked problem, although history may provide a guide. Teams that approach wicked problems must literally make things up as they go along.

- There is always more than one explanation for a wicked problem, with the appropriateness of the explanation depending greatly on the individual perspective of the designer.

- Every wicked problem is a symptom of another problem. The interconnected quality of socio-economic political systems illustrates how, for example, a change in education will cause new behavior in nutrition.

- No mitigation strategy for a wicked problem has a definitive scientific test because humans invented wicked problems and science exists to understand natural phenomena.

- Offering a “solution” to a wicked problem frequently is a “one shot” design effort because a significant intervention changes the design space enough to minimize the ability for trial and error.

- Every wicked problem is unique.

- Designers attempting to address a wicked problem must be fully responsible for their actions. 1

Based on these characteristics, not all hard-to-solve problems are wicked, only those with an indeterminate scope and scale. So most social problems—such as inequality, political instability, death, disease, or famine— are wicked. They can’t be “fixed.” But because of the role of design in developing infrastructure, designers can play a central role in mitigating the negative consequences of wicked problems and positioning the broad trajectory of culture in new and more desirable directions. This mitigation is not an easy, quick, or solitary exercise. While traditional circles of entrepreneurship focus on speed and agility, designing for impact is about staying the course through methodical, rigorous iteration. Due to the system qualities of these large problems, knowledge of science, economics, statistics, technology, medicine, politics, and more are necessary for effective change. This demands interdisciplinary collaboration, and most importantly, perseverance.

A Large-Scale Distraction

Why don’t we already focus our efforts on wicked problems? It seems that our powerful companies and consultancies have become distracted by a different type of problem: differentiation . Innovation describes some form of differentiation or newness. But in product design and product development, tiered releases and differentiation often replace innovation, although they often are claimed as such. Consider the automotive industry, where vehicles in an existing brand are introduced each year with only subtle aesthetic or feature changes. For example, except for slight interior changes and a few new safety features, the 2012 Ford F-150 is the same as the vehicle offered the year before. 2 This phenomenon also is true of other industries, such as toys, appliances, consumer electronics, fashion, even foods, beverages, and services.

This idea of constant but meaningless change drives a machine of consumption, where advertisers pressure those with extra purchasing power into unnecessary upgrades through a fear of being left behind. Consultants and product managers craft product roadmaps that describe the progressive qualities of incremental changes. In fact, it’s considered a best practice and a standard operating procedure to launch subsequent releases of the same product—with minor cosmetic changes—in subsequent months after the original product’s launch. For example, between its 1990 launch and the end of 2004, Canon released 11 versions of its Rebel camera (in 1990, 1992, 1993, 1996, 1999, February and September of 2002, March and September of 2003, April and September of 2004). 3 And Apple has released a new version of the iPod every year since its 2001 launch. 4

This constant push is characterized as a “release cycle”—the amount of time between versions of a product reaching the market. For most of industrialized history, a release cycle for a product was a year or more; complicated offerings like vehicles typically took three or more years from product conception to launch. But technology has afforded advances not only in our products but in the way we make them, so the release cycle has shrunk—a lot. Advances in tooling and manufacturing, the influx of cheap and generic pre-made components, and the ability for software-based firmware upgrades have accelerated product release cycles to three to six months.

Tooling ensures only incremental design change. It describes the process of creating individual, giant machines that will cut, grind, injection-mold, and robotically create a particular product. The tools used to produce an Apple computer are unique to (and probably owned by) Apple, and their production is one of the most expensive parts of the product development process. For example, a simple, small die-cast tool to produce 50,000 low-quality aluminum objects may cost $25,000. It’s in the company’s best interest to use the tool as many times as possible before it begins to fall apart, so the tool begins to act as a design constraint for future product releases. Put another way, if our tool was designed to produce 50,000 objects, and we’ve only made and sold 25,000, it makes financial sense for the next version of our product to use the same tool.

Original Equipment Manufacturing (OEM) contributes to the increased speed of product cycles and is another deterrent to quality and innovation. These are generic parts that manufacturers can use rather than producing their own, decreasing the time to market by skipping the tooling process. For example, a camera company can select OEM camera bezels and internal components. After adding the logo to the sourced materials, this hypothetical company can begin shipping cameras. The company can then differentiate its OEM parts by investing time in software, adding digital features and functions to physical products to distinguish these products.

The primary driver behind incremental, mostly cosmetic innovation and a constant push of releases that leverage OEM parts is simple: quarterly profits . Every three months, Fortune 500 companies report their earnings to investors. If a company reports losses—or even less-than-expected gains—the price of a stock drops, investors lose money, and those with the most shares lose the most money. So stockholders want the company to make as much money as possible in three-month increments . And these short increments constrain any activities and initiatives that take longer than three months. Revolutionary products usually take much, much longer than three months to conceive, design, and build. Unlike a Version 3 product that can leverage an existing manufacturing plant, process, and supply and distribution chains, a new product’s infrastructure must be built from scratch.

People who work at big companies try to create these revolutionary products. But each time profits are reported, the inevitable reorganization occurs—management’s attempt to show investors increased productivity, refined or repositioned strategy, and controlled spending. This reorganization can literally move people to another area of a company or to another company altogether, and in this movement, product development initiatives are lost. Witness the early death of Microsoft Kin or HP’s TouchPad—products that internal reorganizations removed from the marketplace before they could prove their efficacy. The Kin barely lasted forty-eight days on the market 5 , while TouchPad was canceled after seven weeks 6 ; discussions of their death typically focus on internal fighting, misalignment with a given market strategy, cost minimization, or confusion about the products’ position within the brand—rather than on the products themselves.

Ultimately, then, companies and individuals engaged in mass production are incented to drive prices down, produce the same thing over and over, innovate slowly, create differentiation in product lines only through cosmetic changes and minor feature augmentations, and to relentlessly keep making stuff . If we look to major brands and corporations to manage the negative consequences resulting from their work or even to drive social change and innovation, we’ll be discouraged. Social change requires companies to escape the constant drive towards quarterly profits. Even those who find profitability in the social sector—and there are countless examples—require a longer iteration period than three months, so social change is destined to be ignored by the large, publically traded corporations that possess most of the wealth and capability.

Download the free online version of this book.

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

📬 Sign Up for Our Amazing Newsletter!

Writing result-oriented ad copy is difficult, as it must appeal to, entice, and convince consumers to take action.

How to Solve Wicked Problems, with Dr. Paul Hanstedt

Dr. Paul Hanstedt , Director of the Houston H. Harte Center for Teaching and Learning at Washington and Lee University and author of Creating Wicked Students: Designing Courses For a Complex World talks about the need to create wicked students ready to solve the future’s most wicked problems.

We need to encourage our students to become wicked thinkers in order to tackle the world’s most wicked problems. This means embracing lateral thinking, persistence, and creative, long-term problem solving.

Wicked problems are defined as more than just 'difficult': they are almost never solved after just one attempt.

To solve a wicked problem requires creativity, innovation, new ways of thinking, and, often, teamwork over a long period of time.

Are our students wicked enough?

Defining Wicked Problems

According to Dr. Hanstedt, “A wicked problem is a problem where the parameters of the challenge are in flux.” For example: the ever-changing challenges of daily life during COVID-19.

At its core, a wicked problem may not even be solvable, but getting closer to an answer that mitigates the challenge is a goal for the greater solution.

Solving a wicked problem takes both the courage to make the attempt despite probable defeat and the humility to identify what went wrong and try again.

Wicked problems may change over time, impacted by factors like:

- Interdisciplinary knowledge

“Oftentimes there are conflicting answers and ways of interpreting what's going on with a wicked problem," Dr. Hanstedt observes, "which just adds to that volatility, that difficulty of solving it.”

It’s clear that we urgently need to instill the competencies of a wicked problem solver in our students — but how?

Wicked Problem Solvers

To become wicked problem solvers, students must be persistent. Persistence means not only accepting failure, but also growing from experience over time.

When students face a situation that they’ve never seen before, one that perhaps cannot be solved completely or perfectly, they'll need to explore how to translate and apply ideas from different fields. They need to keep trying to make progress toward a solution.

Dr. Hanstedt describes this quality as “an experimental spirit.”

Wicked Problems in the Classroom

A wicked classroom, designed specifically with the goal of training problem solvers, treats content as a tool to solve problems.

For example, the discipline of chemistry is a way to solve problems about elements. Similarly, the field of philosophy is a way to solve problems about ideas, and history is a set of techniques and methodologies to understand, reconcile, or solve the complexities of the past.

A course designed around wicked problems asks this question:

What are you going to do with the content?

Room for Stumbling

Wicked classrooms give students the space they need to stumble and fall.

If we want students to build resilience and persistence, we need to design a classroom in which stumbling is encouraged and rewarded, rather than treated as detrimental.

Room for Riddling

One of the best techniques to encourage long-term lateral thinking that Dr. Hanstedt mentions is to play with riddles. For example, posing a riddle like this one:

A person walks into a bar and asks for a glass of water. The bartender looks at the person, pulls out a gun, and points it at them. The person thanks the bartender and leaves. What’s going on? You can only ask yes or no questions to find out.

This type of problem allows students to grow comfortable with challenges that can’t be solved immediately. By learning how to linger in uncertainty, students overcome their fear of complexity.

Starting Monday with a riddle for the week, or closing a novel at a suspenseful moment and asking students to forecast upcoming events are fun, easy ways to accustom students to accepting a lack of an immediate answer.

P.S. Find the answer to the riddle at the end of this blog.

Action Steps for Parents

1 - ask questions without answers.

Encourage exploration and curiosity by asking open-ended questions without providing an answer. Instead, ask your children for their ideas and discuss possibilities with them.

When your children ask, “Why is such and such?”, you can send the question back by asking, “Huh, what do you think?”

2 - Play with Riddles

Use lateral thinking games, brain teasers, minute mysteries, or detective riddles for family fun, as well as to model how to approach situations that may not make sense right away.

3 - Face Discomfort Willingly

Evaluate your willingness to face situations that make you uncomfortable.

“This is really a key component with a wicked problem,” Dr. Hanstedt says. “We need to be comfortable with discomfort and recognize that discomfort is oftentimes the thing that creates a catalyzing creative space that keeps us moving forward.”

Support this skill in your children through extracurriculars like theater, music, and other cooperative group activities, whether they participate in schools or independently. As Dr. Hanstedt points out, notable ideas are often collaborative.

Guest Resources

- Dr. Paul Hanstedt's website

- Washington and Lee University

- Creating Wicked Students: Designing Courses For a Complex World by Paul Hanstedt

- Two-Minute Mysteries by Donald J. Sobol

- Raising Problem Solvers Guidebook by Art of Problem Solving

The Answer to the Riddle?

The person has hiccups.

This episode was brought to you by Art of Problem Solving , where students train to become the great problem solvers of tomorrow.

To get weekly episode summaries right to your inbox, follow the podcast at the bottom of this page or anywhere you get podcasts. Ideas for the show? Reach us at [email protected] .

Episode Transcript

Dr. paul hanstedt q&a [1:51].

Eric Olsen : On today's episode, Dr. Paul Hanstedt, director of the Houston H. Hart Center for Teaching and Learning at Washington and Lee University, and author of Creating Wicked Students: Designing Courses for a Complex World, talks about the need to raise wicked students, ready to solve the future's most wicked problems. Paul, what are wicked problems?

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : A wicked problem is a problem where the parameters of the challenge are in flux. So what they look like on Tuesday, what they look like a month from Tuesday, what they look like six months from Tuesday are going to be completely different. Think about something like, for instance, COVID. When it first came out, we weren't sure if we were supposed to wear masks or not. We were all wiping our groceries down. So sort of figuring out the problem along the way, and our understanding keeps evolving. That's one criteria for what makes a wicked problem.

Another criteria would be that they're probably not completely solvable, that there's not the perfect answer. Just sitting out there and all we need to do is find that, and then we're fine. More, it's moving toward an answer, getting closer to an answer. And again, COVID is a good example of that. It's probably never going to go away, but what can we do to sort of mitigate the challenge of it?

Other factors come into play. Oftentimes it requires a drawing knowledge from multiple fields. Again, COVID, if it were just a science problem, we'd be done, but clearly politics comes into play. Clearly religion, sociology, economics, race, all of these things can be a factor, geography. And then I would also say kind of related to that is oftentimes as conflicting answers in ways of interpreting what's going on with a wicked problem, which just adds to that volatility, that difficulty of solving it.

Eric Olsen : Hmm. Then describe the competencies of a wicked problem solver. How should we be training our students? How do we raise them to be ready for whatever complexity that their future careers might have in store?

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : Right. Well, one of the main criteria is they need to be used to not having it work when they try to fix it, right? Which is another way, sometimes I use the word failure, but what I really mean is they're going to stumble, they're going to fall,. They're going to have to get back up, and they're going to have to try again, because when we're facing something we haven't seen before and something that maybe can't be solved perfectly, things are going to go wrong. And so that ability to look at the situation carefully, be deliberate in responding, not just kind of go from have a gut reaction or a knee jerk response, think about it carefully, draw from different fields, take ideas that maybe don't seem applicable because they're from over here in the sciences, but this is a humanities problem, or they're from over here in the social sciences, but this is a natural science problem, and sort of translate ideas from one area to another. That's important.

So I think an experimental spirit and a willingness to when that experiment doesn't work, to step back, to reconsider, to look at it again and to move forward, which is a strange combination, right? Of courage to try in the face of probable defeat, and also the humility to go, "Well, it didn't work this time, but I'm going to keep going."

Difference Between A Traditional Classroom And A Wicked Classroom [5:18]

Eric Olsen : And so, in your opinion, what's the biggest difference between a traditional classroom and a classroom designed specifically with this goal of training wicked problem solvers?

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : I love this. Okay, so this past weekend I was at my son's college and I gave a talk. And afterwards, a guy who taught chemistry came up to me. And he was in the seventies. He'd been teaching for years, highly respected. And he said, "Listen, I want to rename my courses. I always tell my students, listen, this is not a chemistry course. This is a problem solving course. Chemistry is what we use in this setting to solve the problem." And so I think what that gets to is a traditional course says, "I've got content. You need to know that content and then you'll be fine." A wicked course of a problem solving course says, "There are problems. I've got some tools that I'm going to provide you to use to solve that problem."

So history is trying to solve, it's using particular techniques and methodologies to try to solve the mystery of the past, the complexities the past, to reconcile things that don't make sense. Philosophy classrooms are taking the logical problems that have challenged us for years and years and years. Our use example of chemistry, physics is trying to resolve issues where we can't even see the things that we're talking about, but we're still trying to answer it. So I think that's a major difference. A traditional course says, "There's content. Once you know that content, you're fine." Wicked classes, "Content is important. You have to know the content, but what are you going to do with the content? And then again, that issue of what does it take to be a problem solver? How are you not going to get it right?"

So there's implications for that too. If our students are going to stumble and fall, a traditional classroom oftentimes doesn't have many, much space for that. You get graded at everything you do. Well, if you're going to stumble and fall, we know you're going to stumble and fall, how do we make space? So that stumbling and falling doesn't get punished in such a way that nobody wants to do it anymore?

Eric Olsen : Paul, so let's say we're convinced of the premise. We want our kids to be these wicked problem solvers, able to help solve COVID-39 faster than our generation solved COVID-19. How then shall we teach? How then shall we parent?

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : Hmm, well parenting, that's an interesting question. So one of the things actually I often do when I'm presenting on wicked problems is I'll toss out some riddles. A man walks into a bar, asks for glass of water. The bartender looks at him, pulls out a gun, points it at the man. The man says, "Thank you," and turns around and walks out. What's going on here? You can ask me yes or no questions. Louise is going home. Suddenly sees somebody in front of her, turns around and goes back where she came from. What's going on? You can ask me yes or no questions. There's a plot of land in Charlottesville, Virginia, right next to the railroad tracks, in an underprivileged neighborhood. People want to develop that land in the best way possible to make the most money for the city. But the people in the neighborhood want to have a park there. What do you do?

And so part of where I'm going with this, and part of the reason that I open presentations like this, is I want to involve people in puzzles, in problem solving. And I want to get him used to the idea that sometimes puzzles make perfect sense, but other times they don't. A man asking for a glass of water. Why would a guy point a gun at him? That makes no sense. And then why would the guy thank him? That makes no sense either. But then if I say something like, and I'm going to give away one of my best riddles here, but if I say something like, somebody asks, "Does a man have hiccups?" Everybody in the room goes, "Oh." And if they get that on the first one as a group, then the second one and the third one fall like dominoes. And oftentimes, if they don't get that on the first one, then the second one and the third one stay standing.

So how do we raise our kids? Traveling, traveling through Asia with my kids 10 years ago, we would ask these riddles with the yes or no questions to keep them busy at the dinner table when the food was taking too long. Play with riddles, ask questions. Don't feel like you always have to have the answer. We get a lot of that as a parent. "Why, why, why, why?" Well, it's fair to turn around and say, "Well, why do you think? What are your ideas on this?" And when they say, "I don't know," say, "Well, are you sure? Do you have any ideas at all?"

So ask the questions. Ask the questions about the things that are uncertain and unsolvable. Encourage exploration and curiosity. And it's fair as well to kind of also say, "Well, here are three possibilities. Which one do you think is the best one?", because a wicked problem doesn't mean anything goes. A wicked problem just means that we need to be more careful and more thoughtful about what we're thinking about.

Helping Students Become So Used to Wicked Problems They’re No Longer Scared of Them [10:40]

Eric Olsen : Really love that, Paul. It's a deeply shared philosophy that we talk about a lot at APS that we want to continually present students with very, very difficult challenges from such a very early age that they're used to it. They're so used to living in the complex, they're no longer terrified of it anymore.

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I think about a teacher that I had years ago, who, when he wanted to get us to read, he stopped, he read a book out loud, and then he stopped right at the scene where the hero fell down and didn't move. And then he closed the book and said, "If you want to know how it ends." And boy, a bunch of fifth graders lining up to read that book. Right? And there's nothing that says, if we have Monday morning riddles in our classes, there's nothing that says we have to solve it. Isn't it intriguing to get to the end of 20 minutes and say, "Well, keep working on it all week long. I will take any ideas that you have. We'll come back to the next riddle, next week, Monday." That's part of the joy. We always talk about lifelong learners, but then we answer the question as though there's nothing left to learn.

How Parents And Teachers Should Think About Raising Wicked Problem Solvers? [11:43]

Eric Olsen : So Paul, maybe leave us there. You have this repository and knowledge of teasers and challenges in your head that you use to help your own children when you were going across Asia. Any next steps advice for parents looking to raise wicked problem solvers? Where's this book of riddles we can use for our own students? How else should we think about that challenge?

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : Yeah, I think honestly, if you look at my phone, there's all these screen captures from years ago of I think they're called two minute riles or something like that. But the bigger question I think is also kind of thinking about what can we do at home? How can we approach things at home? What are the conversations we have at the dinner table? How do we approach things that don't make sense? What is our willingness to face things that make us uncomfortable? This is really a key component with a wicked problem, I think, is we need to be comfortable with discomfort and recognize that discomfort is oftentimes the thing that creates creative space, a catalyzing creative space that keeps us moving forward.

I think as well, thinking about it on the local school level and on the regional and on the state level what's being rewarded? In Virginia, we have the standards of learning, and they have a lot of multiple choice on there. And I remember my fifth grader saying, "Multiple choice are the best because they're so easy."

"You don't even have to know," he says. "You can figure it out half the time." So what can we do to nudge the systems around us?

And I would also kind of point out that there are things, extracurriculars, that can we make sure that they're occurring in our neighborhood schools? Theater, because theater is a wicked problem. Right? How do we produce this? How do we make it engaging? How do we make it entertaining? How do you occupy this character? How do we like this? How do we create the set? Chess, music, all of these things. And that idea and all of these worth noting are collaborative. They're people working together, which is kind of how the world works as opposed to individualized performance. Right?

Yeah, I know. Right? But then we had two years living at home and we missed communities, so…

Download AoPS’ Raising Problem Solvers Guidebook [14:15]

Eric Olsen : That concept of nudging the systems around us is so important. And speaking of nudging, have you downloaded our Raising Problem Solvers guidebook yet? It's full of helpful strategies to support and challenge advanced learners, curriculum recommendations straight from our Art of Problem Solving families, our STEM gift guide, free resource recommendations, and much, much more. It's the perfect next step to help you navigate and build an educational plan that's right for your family. Download our Raising Problem Solvers Guidebook for free today.

Dr. Paul Hanstedt Rapid Fire [14:56]

Eric Olsen : It's now time for our rapid fire segment called Problem Solved where we ask the guest to solve incredibly complex and difficult education issues in single soundbites. Paul, what's one thing about K-12 education you wish you could snap your fingers and problem solved, it's fixed?

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : Get rid of grades. Is that quick enough?

Eric Olsen : That's perfect. If you could go back and give your kid-self advice on their educational journey, what would it be?

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : Keep drawing pictures.

Eric Olsen : Hmm, what part of education do you think or hope looks the most different 10 years from now?

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : In all education, again, I would say our approach to grades. Are there ways we can give more effective feedback rather than a numeric or letter grade that says very little and becomes the prize rather than the meaningful learning.

Eric Olsen: And what's your best advice for parents looking to raise future problem solvers?

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : Ask questions back. when they say, "Why is such and such?", you say, "Huh, what do you think?", or, "Maybe it's this, or maybe it's this, or maybe it's this. Which one?"

Eric Olsen: And listeners, we'd love to hear your answers as well. So email us at [email protected] with your best advice for raising future problem solvers. And we'll read our favorites on future episodes.

Paul, thanks so much for joining us today.

Dr. Paul Hanstedt : My pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Subscribe for news, tips and advice from AoPS

Art of problem solving, related articles, roadschooling, with kay akpan and robyn robledo, what kinds of students does mit look for, with chris peterson, how improv can train innovators, with deana criess.

More Articles

Sapienship, with dr. jim clarke, beast academy moves mankato students up an additional 1-2 grade levels on national map assessment scores, expanding diversity in stem, with meena boppana, the math of big-money lotteries: your chances of winning the powerball jackpot, taking math education to the next level, with po-shen loh, the math of game shows: who wants to be a millionaire, more episodes, wonder, with dr. frank keil, learning stem through fiction, with dr. pamela cosman, managing academic expectations, with charlene wang, edtech at-home, with monica burns, learned helplessness, with vida john, receive weekly podcast summaries right to your inbox, get weekly podcast summaries/takeaways.

By clicking this button, I consent to receiving AoPS communications, and confirm that I am over 13, or under 13 and already a member of the Art of Problem Solving community. View our Privacy Policy .

Aops programs

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Policy

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Policy and Society

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

The concept of wicked problems, thinking about wickedness, wickedness or merely complexity, toward a research program, summary and conclusions, disclosure statement, notes on contributor.

- < Previous

What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

B Guy Peters, What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program, Policy and Society , Volume 36, Issue 3, September 2017, Pages 385–396, https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1361633

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The concept of wicked problems has become a fad in contemporary policy analysis, with any number of problems being labeled as “wicked”. However, if many of these problems are analyzed using a strict definition of the concept they do not meet the criteria. Building on this analysis, I have developed a research program to investigate the extent to which even those problems usually thought to be wicked are actually that difficult.

Much of our discussion of policy problems, and the policy-making designed to ameliorate those problems, is based on functional or instrumental conceptions of the policy. We talk about social welfare issues or defense issues, or alternatively we talk about regulatory policy issues or issues of grants and subsidies. We Peters and Hoornbeek ( 2005 ); (see also Hoornbeek, this issue) have argued in the past that policy analysis can make more progress by examining the underlying analytic dimensions of policies, rather than the familiar functional categories. In the earlier paper we examined a number of those underlying dimensions such as scale, divisibility and monetization, and in this paper I will extend the analysis to examine the concept of ‘wicked problems’.

The concept of wicked problems was developed in the planning literature (Rittel & Webber, 1973 ) to describe emerging policy problems that did not correspond neatly to the conventional models of policy analysis used at the time. The argument in this paper was that the relatively easy policy issues had been addressed, and the future would be more demanding. These emerging problems were defined as complex, involving multiple possible causes and internal dynamics that could not assumed to be linear, and have very negative consequences for society if not addressed properly. The difficulty, rather obviously was, how could the policy analyst and his or her government know ex ante what an adequate solution to these problems might be?