SLO campus power outage. Classes starting at 8:45 AM and earlier cancelled today. Next update by 8:15am

- Cuesta College Home

- Current Students

- Student Success Centers

Study Guides

- Critical Thinking

Decision-making and Problem-solving

Appreciate the complexities involved in decision-making & problem solving.

Develop evidence to support views

Analyze situations carefully

Discuss subjects in an organized way

Predict the consequences of actions

Weigh alternatives

Generate and organize ideas

Form and apply concepts

Design systematic plans of action

A 5-Step Problem-Solving Strategy

Specify the problem – a first step to solving a problem is to identify it as specifically as possible. It involves evaluating the present state and determining how it differs from the goal state.

Analyze the problem – analyzing the problem involves learning as much as you can about it. It may be necessary to look beyond the obvious, surface situation, to stretch your imagination and reach for more creative options.

seek other perspectives

be flexible in your analysis

consider various strands of impact

brainstorm about all possibilities and implications

research problems for which you lack complete information. Get help.

Formulate possible solutions – identify a wide range of possible solutions.

try to think of all possible solutions

be creative

consider similar problems and how you have solved them

Evaluate possible solutions – weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each solution. Think through each solution and consider how, when, and where you could accomplish each. Consider both immediate and long-term results. Mapping your solutions can be helpful at this stage.

Choose a solution – consider 3 factors:

compatibility with your priorities

amount of risk

practicality

Keys to Problem Solving

Think aloud – problem solving is a cognitive, mental process. Thinking aloud or talking yourself through the steps of problem solving is useful. Hearing yourself think can facilitate the process.

Allow time for ideas to "gel" or consolidate. If time permits, give yourself time for solutions to develop. Distance from a problem can allow you to clear your mind and get a new perspective.

Talk about the problem – describing the problem to someone else and talking about it can often make a problem become more clear and defined so that a new solution will surface.

Decision Making Strategies

Decision making is a process of identifying and evaluating choices. We make numerous decisions every day and our decisions may range from routine, every-day types of decisions to those decisions which will have far reaching impacts. The types of decisions we make are routine, impulsive, and reasoned. Deciding what to eat for breakfast is a routine decision; deciding to do or buy something at the last minute is considered an impulsive decision; and choosing your college major is, hopefully, a reasoned decision. College coursework often requires you to make the latter, or reasoned decisions.

Decision making has much in common with problem solving. In problem solving you identify and evaluate solution paths; in decision making you make a similar discovery and evaluation of alternatives. The crux of decision making, then, is the careful identification and evaluation of alternatives. As you weigh alternatives, use the following suggestions:

Consider the outcome each is likely to produce, in both the short term and the long term.

Compare alternatives based on how easily you can accomplish each.

Evaluate possible negative side effects each may produce.

Consider the risk involved in each.

Be creative, original; don't eliminate alternatives because you have not heard or used them before.

An important part of decision making is to predict both short-term and long-term outcomes for each alternative. You may find that while an alternative seems most desirable at the present, it may pose problems or complications over a longer time period.

- Uses of Critical Thinking

- Critically Evaluating the Logic and Validity of Information

- Recognizing Propaganda Techniques and Errors of Faulty Logic

- Developing the Ability to Analyze Historical and Contemporary Information

- Recognize and Value Various Viewpoints

- Appreciating the Complexities Involved in Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Being a Responsible Critical Thinker & Collaborating with Others

- Suggestions

- Read the Textbook

- When to Take Notes

- 10 Steps to Tests

- Studying for Exams

- Test-Taking Errors

- Test Anxiety

- Objective Tests

- Essay Tests

- The Reading Process

- Levels of Comprehension

- Strengthen Your Reading Comprehension

- Reading Rate

- How to Read a Textbook

- Organizational Patterns of a Paragraph

- Topics, Main Ideas, and Support

- Inferences and Conclusions

- Interpreting What You Read

- Concentrating and Remembering

- Converting Words into Pictures

- Spelling and the Dictionary

- Eight Essential Spelling Rules

- Exceptions to the Rules

- Motivation and Goal Setting

- Effective Studying

- Time Management

- Listening and Note-Taking

- Memory and Learning Styles

- Textbook Reading Strategies

- Memory Tips

- Test-Taking Strategies

- The First Step

- Study System

- Maximize Comprehension

- Different Reading Modes

- Paragraph Patterns

- An Effective Strategy

- Finding the Main Idea

- Read a Medical Text

- Read in the Sciences

- Read University Level

- Textbook Study Strategies

- The Origin of Words

- Using a Dictionary

- Interpreting a Dictionary Entry

- Structure Analysis

- Common Roots

- Word Relationships

- Using Word Relationships

- Context Clues

- The Importance of Reading

- Vocabulary Analogies

- Guide to Talking with Instructors

- Writing Help

Dual Enrollment Program Leads CA in Student Participation

Miossi art gallery presents: "the outsiders from the other side", cuesta college's fall semester begins aug. 12.

Short term classes available now.

Register Today!

Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

Work Life is now on YouTube! Watch our new short documentary series here .

This is how effective teams navigate the decision-making process

Zero Magic 8 Balls required.

Get stories like this in your inbox

Flipping a coin. Throwing a dart at a board. Pulling a slip of paper out of a hat.

Sure, they’re all ways to make a choice. But they all hinge on random chance rather than analysis, reflection, and strategy — you know, the things you actually need to make the big, meaty decisions that have major impacts.

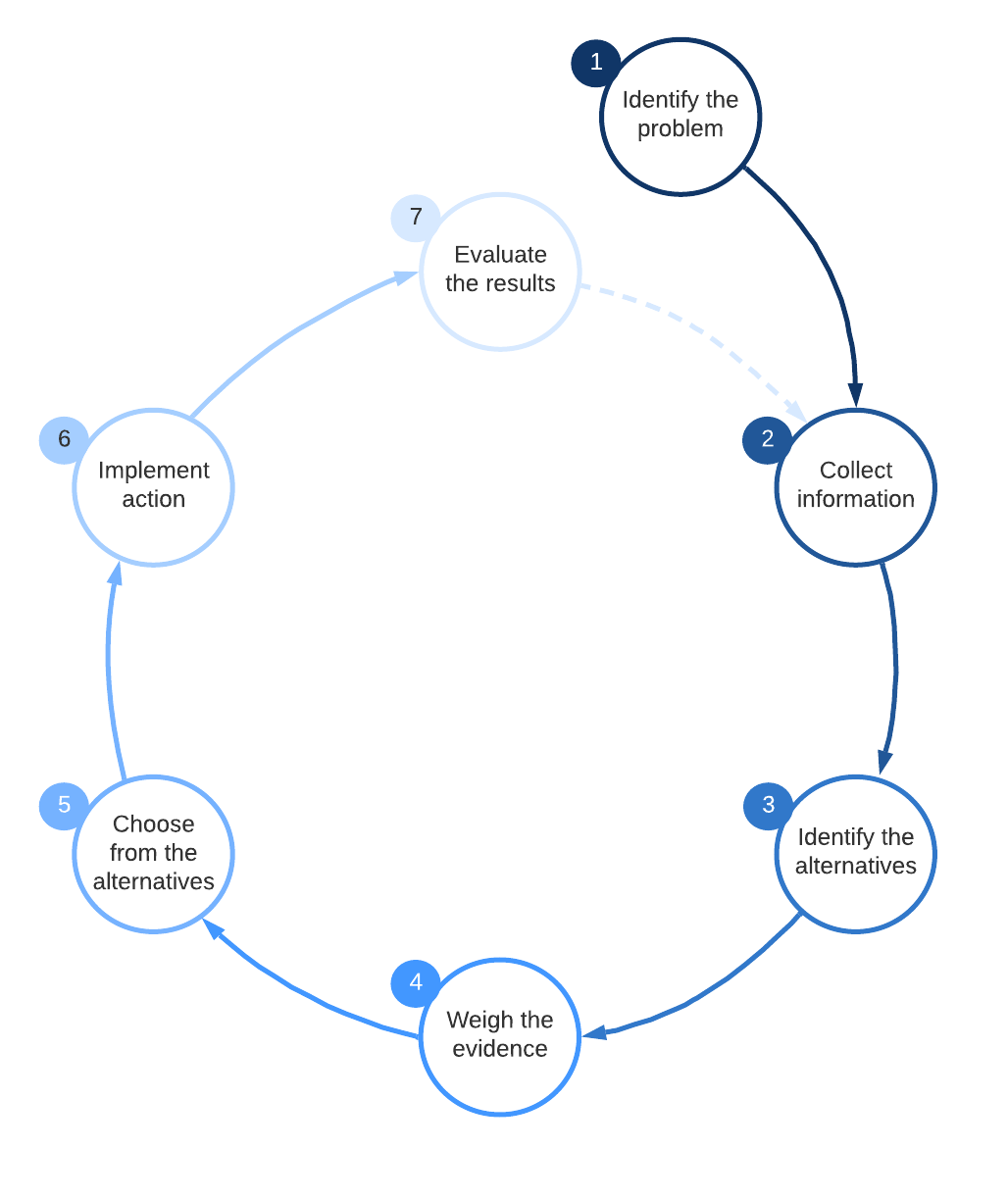

So, set down that Magic 8 Ball and back away slowly. Let’s walk through the standard framework for decision-making that will help you and your team pinpoint the problem, consider your options, and make your most informed selection. Here’s a closer look at each of the seven steps of the decision-making process, and how to approach each one.

Step 1: Identify the decision

Most of us are eager to tie on our superhero capes and jump into problem-solving mode — especially if our team is depending on a solution. But you can’t solve a problem until you have a full grasp on what it actually is .

This first step focuses on getting the lay of the land when it comes to your decision. What specific problem are you trying to solve? What goal are you trying to achieve?

How to do it:

- Use the 5 whys analysis to go beyond surface-level symptoms and understand the root cause of a problem.

- Try problem framing to dig deep on the ins and outs of whatever problem your team is fixing. The point is to define the problem, not solve it.

⚠️ Watch out for: Decision fatigue , which is the tendency to make worse decisions as a result of needing to make too many of them. Making choices is mentally taxing , which is why it’s helpful to pinpoint one decision at a time.

2. Gather information

Your team probably has a few hunches and best guesses, but those can lead to knee-jerk reactions. Take care to invest adequate time and research into your decision.

This step is when you build your case, so to speak. Collect relevant information — that could be data, customer stories, information about past projects, feedback, or whatever else seems pertinent. You’ll use that to make decisions that are informed, rather than impulsive.

- Host a team mindmapping session to freely explore ideas and make connections between them. It can help you identify what information will best support the process.

- Create a project poster to define your goals and also determine what information you already know and what you still need to find out.

⚠️ Watch out for: Information bias , or the tendency to seek out information even if it won’t impact your action. We have the tendency to think more information is always better, but pulling together a bunch of facts and insights that aren’t applicable may cloud your judgment rather than offer clarity.

3. Identify alternatives

Use divergent thinking to generate fresh ideas in your next brainstorm

Blame the popularity of the coin toss, but making a decision often feels like choosing between only two options. Do you want heads or tails? Door number one or door number two? In reality, your options aren’t usually so cut and dried. Take advantage of this opportunity to get creative and brainstorm all sorts of routes or solutions. There’s no need to box yourselves in.

- Use the Six Thinking Hats technique to explore the problem or goal from all sides: information, emotions and instinct, risks, benefits, and creativity. It can help you and your team break away from your typical roles or mindsets and think more freely.

- Try brainwriting so team members can write down their ideas independently before sharing with the group. Research shows that this quiet, lone thinking time can boost psychological safety and generate more creative suggestions .

⚠️ Watch out for: Groupthink , which is the tendency of a group to make non-optimal decisions in the interest of conformity. People don’t want to rock the boat, so they don’t speak up.

4. Consider the evidence

Armed with your list of alternatives, it’s time to take a closer look and determine which ones could be worth pursuing. You and your team should ask questions like “How will this solution address the problem or achieve the goal?” and “What are the pros and cons of this option?”

Be honest with your answers (and back them up with the information you already collected when you can). Remind the team that this isn’t about advocating for their own suggestions to “win” — it’s about whittling your options down to the best decision.

How to do it:

- Use a SWOT analysis to dig into the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of the options you’re seriously considering.

- Run a project trade-off analysis to understand what constraints (such as time, scope, or cost) the team is most willing to compromise on if needed.

⚠️ Watch out for: Extinction by instinct , which is the urge to make a decision just to get it over with. You didn’t come this far to settle for a “good enough” option!

5. Choose among the alternatives

This is it — it’s the big moment when you and the team actually make the decision. You’ve identified all possible options, considered the supporting evidence, and are ready to choose how you’ll move forward.

However, bear in mind that there’s still a surprising amount of room for flexibility here. Maybe you’ll modify an alternative or combine a few suggested solutions together to land on the best fit for your problem and your team.

- Use the DACI framework (that stands for “driver, approver, contributor, informed”) to understand who ultimately has the final say in decisions. The decision-making process can be collaborative, but eventually someone needs to be empowered to make the final call.

- Try a simple voting method for decisions that are more democratized. You’ll simply tally your team’s votes and go with the majority.

⚠️ Watch out for: Analysis paralysis , which is when you overthink something to such a great degree that you feel overwhelmed and freeze when it’s time to actually make a choice.

6. Take action

Making a big decision takes a hefty amount of work, but it’s only the first part of the process — now you need to actually implement it.

It’s tempting to think that decisions will work themselves out once they’re made. But particularly in a team setting, it’s crucial to invest just as much thought and planning into communicating the decision and successfully rolling it out.

- Create a stakeholder communications plan to determine how you’ll keep various people — direct team members, company leaders, customers, or whoever else has an active interest in your decision — in the loop on your progress.

- Define the goals, signals, and measures of your decision so you’ll have an easier time aligning the team around the next steps and determining whether or not they’re successful.

⚠️Watch out for: Self-doubt, or the tendency to question whether or not you’re making the right move. While we’re hardwired for doubt , now isn’t the time to be a skeptic about your decision. You and the team have done the work, so trust the process.

7. Review your decision

9 retrospective techniques that won’t bore your team to tears

As the decision itself starts to shake out, it’s time to take a look in the rearview mirror and reflect on how things went.

Did your decision work out the way you and the team hoped? What happened? Examine both the good and the bad. What should you keep in mind if and when you need to make this sort of decision again?

- Do a 4 L’s retrospective to talk through what you and the team loved, loathed, learned, and longed for as a result of that decision.

- Celebrate any wins (yes, even the small ones ) related to that decision. It gives morale a good kick in the pants and can also help make future decisions feel a little less intimidating.

⚠️ Watch out for: Hindsight bias , or the tendency to look back on events with the knowledge you have now and beat yourself up for not knowing better at the time. Even with careful thought and planning, some decisions don’t work out — but you can only operate with the information you have at the time.

Making smart decisions about the decision-making process

You’re probably picking up on the fact that the decision-making process is fairly comprehensive. And the truth is that the model is likely overkill for the small and inconsequential decisions you or your team members need to make.

Deciding whether you should order tacos or sandwiches for your team offsite doesn’t warrant this much discussion and elbow grease. But figuring out which major project to prioritize next? That requires some careful and collaborative thought.

It all comes back to the concept of satisficing versus maximizing , which are two different perspectives on decision making. Here’s the gist:

- Maximizers aim to get the very best out of every single decision.

- Satisficers are willing to settle for “good enough” rather than obsessing over achieving the best outcome.

One of those isn’t necessarily better than the other — and, in fact, they both have their time and place.

A major decision with far-reaching impacts deserves some fixation and perfectionism. However, hemming and hawing over trivial choices ( “Should we start our team meeting with casual small talk or a structured icebreaker?” ) will only cause added stress, frustration, and slowdowns.

As with anything else, it’s worth thinking about the potential impacts to determine just how much deliberation and precision a decision actually requires.

Decision-making is one of those things that’s part art and part science. You’ll likely have some gut feelings and instincts that are worth taking into account. But those should also be complemented with plenty of evidence, evaluation, and collaboration.

The decision-making process is a framework that helps you strike that balance. Follow the seven steps and you and your team can feel confident in the decisions you make — while leaving the darts and coins where they belong.

Advice, stories, and expertise about work life today.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Problem Solving and Decision Making

Introduction.

- General Approaches to Problem Solving

- Representational Accounts

- Problem Space and Search

- Working Memory and Problem Solving

- Domain-Specific Problem Solving

- The Rational Approach

- Prospect Theory

- Dual-Process Theory

- Cognitive Heuristics and Biases

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Psychology

- Counterfactual Reasoning

- Critical Thinking

- Heuristics and Biases

- Protocol Analysis

- Psychology and Law

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Data Visualization

- Executive Functions in Childhood

- Remote Work

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Problem Solving and Decision Making by Emily G. Nielsen , John Paul Minda LAST REVIEWED: 26 June 2019 LAST MODIFIED: 26 June 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0246

Problem solving and decision making are both examples of complex, higher-order thinking. Both involve the assessment of the environment, the involvement of working memory or short-term memory, reliance on long term memory, effects of knowledge, and the application of heuristics to complete a behavior. A problem can be defined as an impasse or gap between a current state and a desired goal state. Problem solving is the set of cognitive operations that a person engages in to change the current state, to go beyond the impasse, and achieve a desired outcome. Problem solving involves the mental representation of the problem state and the manipulation of this representation in order to move closer to the goal. Problems can vary in complexity, abstraction, and how well defined (or not) the initial state and the goal state are. Research has generally approached problem solving by examining the behaviors and cognitive processes involved, and some work has examined problem solving using computational processes as well. Decision making is the process of selecting and choosing one action or behavior out of several alternatives. Like problem solving, decision making involves the coordination of memories and executive resources. Research on decision making has paid particular attention to the cognitive biases that account for suboptimal decisions and decisions that deviate from rationality. The current bibliography first outlines some general resources on the psychology of problem solving and decision making before examining each of these topics in detail. Specifically, this review covers cognitive, neuroscientific, and computational approaches to problem solving, as well as decision making models and cognitive heuristics and biases.

General Overviews

Current research in the area of problem solving and decision making is published in both general and specialized scientific journals. Theoretical and scholarly work is often summarized and developed in full-length books and chapter. These may focus on the subfields of problem solving and decision making or the larger field of thinking and higher-order cognition.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Psychology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abnormal Psychology

- Academic Assessment

- Acculturation and Health

- Action Regulation Theory

- Action Research

- Addictive Behavior

- Adolescence

- Adoption, Social, Psychological, and Evolutionary Perspect...

- Advanced Theory of Mind

- Affective Forecasting

- Affirmative Action

- Ageism at Work

- Allport, Gordon

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Ambulatory Assessment in Behavioral Science

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA)

- Animal Behavior

- Animal Learning

- Anxiety Disorders

- Art and Aesthetics, Psychology of

- Assessment and Clinical Applications of Individual Differe...

- Attachment in Social and Emotional Development across the ...

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Childre...

- Attitudinal Ambivalence

- Attraction in Close Relationships

- Attribution Theory

- Authoritarian Personality

- Bayesian Statistical Methods in Psychology

- Behavior Therapy, Rational Emotive

- Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Genetics

- Belief Perseverance

- Bereavement and Grief

- Biological Psychology

- Birth Order

- Body Image in Men and Women

- Bystander Effect

- Categorical Data Analysis in Psychology

- Childhood and Adolescence, Peer Victimization and Bullying...

- Clark, Mamie Phipps

- Clinical Neuropsychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Consistency Theories

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Communication, Nonverbal Cues and

- Comparative Psychology

- Competence to Stand Trial: Restoration Services

- Competency to Stand Trial

- Computational Psychology

- Conflict Management in the Workplace

- Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

- Consciousness

- Coping Processes

- Correspondence Analysis in Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Creativity at Work

- Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Cultural Psychology

- Daily Life, Research Methods for Studying

- Data Science Methods for Psychology

- Data Sharing in Psychology

- Death and Dying

- Deceiving and Detecting Deceit

- Defensive Processes

- Depressive Disorders

- Development, Prenatal

- Developmental Psychology (Cognitive)

- Developmental Psychology (Social)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM...

- Discrimination

- Dissociative Disorders

- Drugs and Behavior

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Psychology

- Educational Settings, Assessment of Thinking in

- Effect Size

- Embodiment and Embodied Cognition

- Emerging Adulthood

- Emotional Intelligence

- Empathy and Altruism

- Employee Stress and Well-Being

- Environmental Neuroscience and Environmental Psychology

- Ethics in Psychological Practice

- Event Perception

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Expansive Posture

- Experimental Existential Psychology

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Eyewitness Testimony

- Eysenck, Hans

- Factor Analysis

- Festinger, Leon

- Five-Factor Model of Personality

- Flynn Effect, The

- Forensic Psychology

- Forgiveness

- Friendships, Children's

- Fundamental Attribution Error/Correspondence Bias

- Gambler's Fallacy

- Game Theory and Psychology

- Geropsychology, Clinical

- Global Mental Health

- Habit Formation and Behavior Change

- Health Psychology

- Health Psychology Research and Practice, Measurement in

- Heider, Fritz

- History of Psychology

- Human Factors

- Humanistic Psychology

- Implicit Association Test (IAT)

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Inferential Statistics in Psychology

- Insanity Defense, The

- Intelligence

- Intelligence, Crystallized and Fluid

- Intercultural Psychology

- Intergroup Conflict

- International Classification of Diseases and Related Healt...

- International Psychology

- Interviewing in Forensic Settings

- Intimate Partner Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Introversion–Extraversion

- Item Response Theory

- Law, Psychology and

- Lazarus, Richard

- Learned Helplessness

- Learning Theory

- Learning versus Performance

- LGBTQ+ Romantic Relationships

- Lie Detection in a Forensic Context

- Life-Span Development

- Locus of Control

- Loneliness and Health

- Mathematical Psychology

- Meaning in Life

- Mechanisms and Processes of Peer Contagion

- Media Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Mediation Analysis

- Memories, Autobiographical

- Memories, Flashbulb

- Memories, Repressed and Recovered

- Memory, False

- Memory, Human

- Memory, Implicit versus Explicit

- Memory in Educational Settings

- Memory, Semantic

- Meta-Analysis

- Metacognition

- Metaphor, Psychological Perspectives on

- Microaggressions

- Military Psychology

- Mindfulness

- Mindfulness and Education

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- Money, Psychology of

- Moral Conviction

- Moral Development

- Moral Psychology

- Moral Reasoning

- Nature versus Nurture Debate in Psychology

- Neuroscience of Associative Learning

- Nonergodicity in Psychology and Neuroscience

- Nonparametric Statistical Analysis in Psychology

- Observational (Non-Randomized) Studies

- Obsessive-Complusive Disorder (OCD)

- Occupational Health Psychology

- Olfaction, Human

- Operant Conditioning

- Optimism and Pessimism

- Organizational Justice

- Parenting Stress

- Parenting Styles

- Parents' Beliefs about Children

- Path Models

- Peace Psychology

- Perception, Person

- Performance Appraisal

- Personality and Health

- Personality Disorders

- Personality Psychology

- Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies: From Car...

- Phenomenological Psychology

- Placebo Effects in Psychology

- Play Behavior

- Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

- Positive Psychology

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Prejudice and Stereotyping

- Pretrial Publicity

- Prisoner's Dilemma

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Procrastination

- Prosocial Behavior

- Prosocial Spending and Well-Being

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Literacy

- Psychological Perspectives on Food and Eating

- Psychology, Political

- Psychoneuroimmunology

- Psychophysics, Visual

- Psychotherapy

- Psychotic Disorders

- Publication Bias in Psychology

- Reasoning, Counterfactual

- Rehabilitation Psychology

- Relationships

- Reliability–Contemporary Psychometric Conceptions

- Religion, Psychology and

- Replication Initiatives in Psychology

- Research Methods

- Risk Taking

- Role of the Expert Witness in Forensic Psychology, The

- Sample Size Planning for Statistical Power and Accurate Es...

- Schizophrenic Disorders

- School Psychology

- School Psychology, Counseling Services in

- Self, Gender and

- Self, Psychology of the

- Self-Construal

- Self-Control

- Self-Deception

- Self-Determination Theory

- Self-Efficacy

- Self-Esteem

- Self-Monitoring

- Self-Regulation in Educational Settings

- Self-Report Tests, Measures, and Inventories in Clinical P...

- Sensation Seeking

- Sex and Gender

- Sexual Minority Parenting

- Sexual Orientation

- Signal Detection Theory and its Applications

- Simpson's Paradox in Psychology

- Single People

- Single-Case Experimental Designs

- Skinner, B.F.

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Small Groups

- Social Class and Social Status

- Social Cognition

- Social Neuroscience

- Social Support

- Social Touch and Massage Therapy Research

- Somatoform Disorders

- Spatial Attention

- Sports Psychology

- Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE): Icon and Controversy

- Stereotype Threat

- Stereotypes

- Stress and Coping, Psychology of

- Student Success in College

- Subjective Wellbeing Homeostasis

- Taste, Psychological Perspectives on

- Teaching of Psychology

- Terror Management Theory

- Testing and Assessment

- The Concept of Validity in Psychological Assessment

- The Neuroscience of Emotion Regulation

- The Reasoned Action Approach and the Theories of Reasoned ...

- The Weapon Focus Effect in Eyewitness Memory

- Theory of Mind

- Therapy, Cognitive-Behavioral

- Thinking Skills in Educational Settings

- Time Perception

- Trait Perspective

- Trauma Psychology

- Twin Studies

- Type A Behavior Pattern (Coronary Prone Personality)

- Unconscious Processes

- Video Games and Violent Content

- Virtues and Character Strengths

- Women and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM...

- Women, Psychology of

- Work Well-Being

- Workforce Training Evaluation

- Wundt, Wilhelm

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.80.149.115]

- 185.80.149.115

- Product overview

- All features

- Latest feature release

- App integrations

- project icon Project management

- Project views

- Custom fields

- Status updates

- goal icon Goals and reporting

- Reporting dashboards

- asana-intelligence icon Asana AI

- workflow icon Workflows and automation

- portfolio icon Resource management

- Capacity planning

- Time tracking

- my-task icon Admin and security

- Admin console

- Permissions

- list icon Personal

- premium icon Starter

- briefcase icon Advanced

- Goal management

- Organizational planning

- Project intake

- Resource planning

- Product launches

- View all uses arrow-right icon

- Work management resources Discover best practices, watch webinars, get insights

- Customer stories See how the world's best organizations drive work innovation with Asana

- Help Center Get lots of tips, tricks, and advice to get the most from Asana

- Asana Academy Sign up for interactive courses and webinars to learn Asana

- Developers Learn more about building apps on the Asana platform

- Community programs Connect with and learn from Asana customers around the world

- Events Find out about upcoming events near you

- Partners Learn more about our partner programs

- Asana for nonprofits Get more information on our nonprofit discount program, and apply.

- Project plans

- Team goals & objectives

- Team continuity

- Meeting agenda

- View all templates arrow-right icon

- Leadership |

- 7 important steps in the decision makin ...

7 important steps in the decision making process

The decision making process is a method of gathering information, assessing alternatives, and making a final choice with the goal of making the best decision possible. In this article, we detail the step-by-step process on how to make a good decision and explain different decision making methodologies.

We make decisions every day. Take the bus to work or call a car? Chocolate or vanilla ice cream? Whole milk or two percent?

There's an entire process that goes into making those tiny decisions, and while these are simple, easy choices, how do we end up making more challenging decisions?

At work, decisions aren't as simple as choosing what kind of milk you want in your latte in the morning. That’s why understanding the decision making process is so important.

What is the decision making process?

The decision making process is the method of gathering information, assessing alternatives, and, ultimately, making a final choice.

Decision-making tools for agile businesses

In this ebook, learn how to equip employees to make better decisions—so your business can pivot, adapt, and tackle challenges more effectively than your competition.

The 7 steps of the decision making process

Step 1: identify the decision that needs to be made.

When you're identifying the decision, ask yourself a few questions:

What is the problem that needs to be solved?

What is the goal you plan to achieve by implementing this decision?

How will you measure success?

These questions are all common goal setting techniques that will ultimately help you come up with possible solutions. When the problem is clearly defined, you then have more information to come up with the best decision to solve the problem.

Step 2: Gather relevant information

Gathering information related to the decision being made is an important step to making an informed decision. Does your team have any historical data as it relates to this issue? Has anybody attempted to solve this problem before?

It's also important to look for information outside of your team or company. Effective decision making requires information from many different sources. Find external resources, whether it’s doing market research, working with a consultant, or talking with colleagues at a different company who have relevant experience. Gathering information helps your team identify different solutions to your problem.

Step 3: Identify alternative solutions

This step requires you to look for many different solutions for the problem at hand. Finding more than one possible alternative is important when it comes to business decision-making, because different stakeholders may have different needs depending on their role. For example, if a company is looking for a work management tool, the design team may have different needs than a development team. Choosing only one solution right off the bat might not be the right course of action.

Step 4: Weigh the evidence

This is when you take all of the different solutions you’ve come up with and analyze how they would address your initial problem. Your team begins identifying the pros and cons of each option, and eliminating alternatives from those choices.

There are a few common ways your team can analyze and weigh the evidence of options:

Pros and cons list

SWOT analysis

Decision matrix

Step 5: Choose among the alternatives

The next step is to make your final decision. Consider all of the information you've collected and how this decision may affect each stakeholder.

Sometimes the right decision is not one of the alternatives, but a blend of a few different alternatives. Effective decision-making involves creative problem solving and thinking out of the box, so don't limit you or your teams to clear-cut options.

One of the key values at Asana is to reject false tradeoffs. Choosing just one decision can mean losing benefits in others. If you can, try and find options that go beyond just the alternatives presented.

Step 6: Take action

Once the final decision maker gives the green light, it's time to put the solution into action. Take the time to create an implementation plan so that your team is on the same page for next steps. Then it’s time to put your plan into action and monitor progress to determine whether or not this decision was a good one.

Step 7: Review your decision and its impact (both good and bad)

Once you’ve made a decision, you can monitor the success metrics you outlined in step 1. This is how you determine whether or not this solution meets your team's criteria of success.

Here are a few questions to consider when reviewing your decision:

Did it solve the problem your team identified in step 1?

Did this decision impact your team in a positive or negative way?

Which stakeholders benefited from this decision? Which stakeholders were impacted negatively?

If this solution was not the best alternative, your team might benefit from using an iterative form of project management. This enables your team to quickly adapt to changes, and make the best decisions with the resources they have.

Types of decision making models

While most decision making models revolve around the same seven steps, here are a few different methodologies to help you make a good decision.

Rational decision making models

This type of decision making model is the most common type that you'll see. It's logical and sequential. The seven steps listed above are an example of the rational decision making model.

When your decision has a big impact on your team and you need to maximize outcomes, this is the type of decision making process you should use. It requires you to consider a wide range of viewpoints with little bias so you can make the best decision possible.

Intuitive decision making models

This type of decision making model is dictated not by information or data, but by gut instincts. This form of decision making requires previous experience and pattern recognition to form strong instincts.

This type of decision making is often made by decision makers who have a lot of experience with similar kinds of problems. They have already had proven success with the solution they're looking to implement.

Creative decision making model

The creative decision making model involves collecting information and insights about a problem and coming up with potential ideas for a solution, similar to the rational decision making model.

The difference here is that instead of identifying the pros and cons of each alternative, the decision maker enters a period in which they try not to actively think about the solution at all. The goal is to have their subconscious take over and lead them to the right decision, similar to the intuitive decision making model.

This situation is best used in an iterative process so that teams can test their solutions and adapt as things change.

Track key decisions with a work management tool

Tracking key decisions can be challenging when not documented correctly. Learn more about how a work management tool like Asana can help your team track key decisions, collaborate with teammates, and stay on top of progress all in one place.

Related resources

How to give and take constructive criticism

Data-driven decision making: A step-by-step guide

Listening to understand: How to practice active listening (with examples)

How executives and individual contributors differ when it comes to AI

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Decision-Making and Problem Solving

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Effective Decision Making

- Decision-Making Framework

- Introduction to Problem Solving

Identifying and Structuring Problems

Investigating Ideas and Solutions

Implementing a Solution and Feedback

- Creative Problem-Solving

Social Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Making decisions and solving problems are two key areas in life, whether you are at home or at work. Whatever you’re doing, and wherever you are, you are faced with countless decisions and problems, both small and large, every day.

Many decisions and problems are so small that we may not even notice them. Even small decisions, however, can be overwhelming to some people. They may come to a halt as they consider their dilemma and try to decide what to do.

Small and Large Decisions

In your day-to-day life you're likely to encounter numerous 'small decisions', including, for example:

Tea or coffee?

What shall I have in my sandwich? Or should I have a salad instead today?

What shall I wear today?

Larger decisions may occur less frequently but may include:

Should we repaint the kitchen? If so, what colour?

Should we relocate?

Should I propose to my partner? Do I really want to spend the rest of my life with him/her?

These decisions, and others like them, may take considerable time and effort to make.

The relationship between decision-making and problem-solving is complex. Decision-making is perhaps best thought of as a key part of problem-solving: one part of the overall process.

Our approach at Skills You Need is to set out a framework to help guide you through the decision-making process. You won’t always need to use the whole framework, or even use it at all, but you may find it useful if you are a bit ‘stuck’ and need something to help you make a difficult decision.

Decision Making

Effective Decision-Making

This page provides information about ways of making a decision, including basing it on logic or emotion (‘gut feeling’). It also explains what can stop you making an effective decision, including too much or too little information, and not really caring about the outcome.

A Decision-Making Framework

This page sets out one possible framework for decision-making.

The framework described is quite extensive, and may seem quite formal. But it is also a helpful process to run through in a briefer form, for smaller problems, as it will help you to make sure that you really do have all the information that you need.

Problem Solving

Introduction to Problem-Solving

This page provides a general introduction to the idea of problem-solving. It explores the idea of goals (things that you want to achieve) and barriers (things that may prevent you from achieving your goals), and explains the problem-solving process at a broad level.

The first stage in solving any problem is to identify it, and then break it down into its component parts. Even the biggest, most intractable-seeming problems, can become much more manageable if they are broken down into smaller parts. This page provides some advice about techniques you can use to do so.

Sometimes, the possible options to address your problem are obvious. At other times, you may need to involve others, or think more laterally to find alternatives. This page explains some principles, and some tools and techniques to help you do so.

Having generated solutions, you need to decide which one to take, which is where decision-making meets problem-solving. But once decided, there is another step: to deliver on your decision, and then see if your chosen solution works. This page helps you through this process.

‘Social’ problems are those that we encounter in everyday life, including money trouble, problems with other people, health problems and crime. These problems, like any others, are best solved using a framework to identify the problem, work out the options for addressing it, and then deciding which option to use.

This page provides more information about the key skills needed for practical problem-solving in real life.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Interpersonal Skills eBooks.

Develop your interpersonal skills with our series of eBooks. Learn about and improve your communication skills, tackle conflict resolution, mediate in difficult situations, and develop your emotional intelligence.

Guiding you through the key skills needed in life

As always at Skills You Need, our approach to these key skills is to provide practical ways to manage the process, and to develop your skills.

Neither problem-solving nor decision-making is an intrinsically difficult process and we hope you will find our pages useful in developing your skills.

Start with: Decision Making Problem Solving

See also: Improving Communication Interpersonal Communication Skills Building Confidence

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

In this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , Simon London speaks with Charles Conn, CEO of venture-capital firm Oxford Sciences Innovation, and McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin about the complexities of different problem-solving strategies.

Podcast transcript

Simon London: Hello, and welcome to this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , with me, Simon London. What’s the number-one skill you need to succeed professionally? Salesmanship, perhaps? Or a facility with statistics? Or maybe the ability to communicate crisply and clearly? Many would argue that at the very top of the list comes problem solving: that is, the ability to think through and come up with an optimal course of action to address any complex challenge—in business, in public policy, or indeed in life.

Looked at this way, it’s no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven-step method. To discuss the art of problem solving, I sat down in California with McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin and also with Charles Conn. Charles is a former McKinsey partner, entrepreneur, executive, and coauthor of the book Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything [John Wiley & Sons, 2018].

Charles and Hugo, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hugo Sarrazin: Our pleasure.

Charles Conn: It’s terrific to be here.

Simon London: Problem solving is a really interesting piece of terminology. It could mean so many different things. I have a son who’s a teenage climber. They talk about solving problems. Climbing is problem solving. Charles, when you talk about problem solving, what are you talking about?

Charles Conn: For me, problem solving is the answer to the question “What should I do?” It’s interesting when there’s uncertainty and complexity, and when it’s meaningful because there are consequences. Your son’s climbing is a perfect example. There are consequences, and it’s complicated, and there’s uncertainty—can he make that grab? I think we can apply that same frame almost at any level. You can think about questions like “What town would I like to live in?” or “Should I put solar panels on my roof?”

You might think that’s a funny thing to apply problem solving to, but in my mind it’s not fundamentally different from business problem solving, which answers the question “What should my strategy be?” Or problem solving at the policy level: “How do we combat climate change?” “Should I support the local school bond?” I think these are all part and parcel of the same type of question, “What should I do?”

I’m a big fan of structured problem solving. By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we’re solving, what are the components of the problem that we’re solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we’ve learned back into a compelling story. That’s all it is, at its heart.

I think sometimes when people think about seven steps, they assume that there’s a rigidity to this. That’s not it at all. It’s actually to give you the scope for creativity, which often doesn’t exist when your problem solving is muddled.

Simon London: You were just talking about the seven-step process. That’s what’s written down in the book, but it’s a very McKinsey process as well. Without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s go through the steps, one by one. You were just talking about problem definition as being a particularly important thing to get right first. That’s the first step. Hugo, tell us about that.

Hugo Sarrazin: It is surprising how often people jump past this step and make a bunch of assumptions. The most powerful thing is to step back and ask the basic questions—“What are we trying to solve? What are the constraints that exist? What are the dependencies?” Let’s make those explicit and really push the thinking and defining. At McKinsey, we spend an enormous amount of time in writing that little statement, and the statement, if you’re a logic purist, is great. You debate. “Is it an ‘or’? Is it an ‘and’? What’s the action verb?” Because all these specific words help you get to the heart of what matters.

Want to subscribe to The McKinsey Podcast ?

Simon London: So this is a concise problem statement.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah. It’s not like “Can we grow in Japan?” That’s interesting, but it is “What, specifically, are we trying to uncover in the growth of a product in Japan? Or a segment in Japan? Or a channel in Japan?” When you spend an enormous amount of time, in the first meeting of the different stakeholders, debating this and having different people put forward what they think the problem definition is, you realize that people have completely different views of why they’re here. That, to me, is the most important step.

Charles Conn: I would agree with that. For me, the problem context is critical. When we understand “What are the forces acting upon your decision maker? How quickly is the answer needed? With what precision is the answer needed? Are there areas that are off limits or areas where we would particularly like to find our solution? Is the decision maker open to exploring other areas?” then you not only become more efficient, and move toward what we call the critical path in problem solving, but you also make it so much more likely that you’re not going to waste your time or your decision maker’s time.

How often do especially bright young people run off with half of the idea about what the problem is and start collecting data and start building models—only to discover that they’ve really gone off half-cocked.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah.

Charles Conn: And in the wrong direction.

Simon London: OK. So step one—and there is a real art and a structure to it—is define the problem. Step two, Charles?

Charles Conn: My favorite step is step two, which is to use logic trees to disaggregate the problem. Every problem we’re solving has some complexity and some uncertainty in it. The only way that we can really get our team working on the problem is to take the problem apart into logical pieces.

What we find, of course, is that the way to disaggregate the problem often gives you an insight into the answer to the problem quite quickly. I love to do two or three different cuts at it, each one giving a bit of a different insight into what might be going wrong. By doing sensible disaggregations, using logic trees, we can figure out which parts of the problem we should be looking at, and we can assign those different parts to team members.

Simon London: What’s a good example of a logic tree on a sort of ratable problem?

Charles Conn: Maybe the easiest one is the classic profit tree. Almost in every business that I would take a look at, I would start with a profit or return-on-assets tree. In its simplest form, you have the components of revenue, which are price and quantity, and the components of cost, which are cost and quantity. Each of those can be broken out. Cost can be broken into variable cost and fixed cost. The components of price can be broken into what your pricing scheme is. That simple tree often provides insight into what’s going on in a business or what the difference is between that business and the competitors.

If we add the leg, which is “What’s the asset base or investment element?”—so profit divided by assets—then we can ask the question “Is the business using its investments sensibly?” whether that’s in stores or in manufacturing or in transportation assets. I hope we can see just how simple this is, even though we’re describing it in words.

When I went to work with Gordon Moore at the Moore Foundation, the problem that he asked us to look at was “How can we save Pacific salmon?” Now, that sounds like an impossible question, but it was amenable to precisely the same type of disaggregation and allowed us to organize what became a 15-year effort to improve the likelihood of good outcomes for Pacific salmon.

Simon London: Now, is there a danger that your logic tree can be impossibly large? This, I think, brings us onto the third step in the process, which is that you have to prioritize.

Charles Conn: Absolutely. The third step, which we also emphasize, along with good problem definition, is rigorous prioritization—we ask the questions “How important is this lever or this branch of the tree in the overall outcome that we seek to achieve? How much can I move that lever?” Obviously, we try and focus our efforts on ones that have a big impact on the problem and the ones that we have the ability to change. With salmon, ocean conditions turned out to be a big lever, but not one that we could adjust. We focused our attention on fish habitats and fish-harvesting practices, which were big levers that we could affect.

People spend a lot of time arguing about branches that are either not important or that none of us can change. We see it in the public square. When we deal with questions at the policy level—“Should you support the death penalty?” “How do we affect climate change?” “How can we uncover the causes and address homelessness?”—it’s even more important that we’re focusing on levers that are big and movable.

Would you like to learn more about our Strategy & Corporate Finance Practice ?

Simon London: Let’s move swiftly on to step four. You’ve defined your problem, you disaggregate it, you prioritize where you want to analyze—what you want to really look at hard. Then you got to the work plan. Now, what does that mean in practice?

Hugo Sarrazin: Depending on what you’ve prioritized, there are many things you could do. It could be breaking the work among the team members so that people have a clear piece of the work to do. It could be defining the specific analyses that need to get done and executed, and being clear on time lines. There’s always a level-one answer, there’s a level-two answer, there’s a level-three answer. Without being too flippant, I can solve any problem during a good dinner with wine. It won’t have a whole lot of backing.

Simon London: Not going to have a lot of depth to it.

Hugo Sarrazin: No, but it may be useful as a starting point. If the stakes are not that high, that could be OK. If it’s really high stakes, you may need level three and have the whole model validated in three different ways. You need to find a work plan that reflects the level of precision, the time frame you have, and the stakeholders you need to bring along in the exercise.

Charles Conn: I love the way you’ve described that, because, again, some people think of problem solving as a linear thing, but of course what’s critical is that it’s iterative. As you say, you can solve the problem in one day or even one hour.

Charles Conn: We encourage our teams everywhere to do that. We call it the one-day answer or the one-hour answer. In work planning, we’re always iterating. Every time you see a 50-page work plan that stretches out to three months, you know it’s wrong. It will be outmoded very quickly by that learning process that you described. Iterative problem solving is a critical part of this. Sometimes, people think work planning sounds dull, but it isn’t. It’s how we know what’s expected of us and when we need to deliver it and how we’re progressing toward the answer. It’s also the place where we can deal with biases. Bias is a feature of every human decision-making process. If we design our team interactions intelligently, we can avoid the worst sort of biases.

Simon London: Here we’re talking about cognitive biases primarily, right? It’s not that I’m biased against you because of your accent or something. These are the cognitive biases that behavioral sciences have shown we all carry around, things like anchoring, overoptimism—these kinds of things.

Both: Yeah.

Charles Conn: Availability bias is the one that I’m always alert to. You think you’ve seen the problem before, and therefore what’s available is your previous conception of it—and we have to be most careful about that. In any human setting, we also have to be careful about biases that are based on hierarchies, sometimes called sunflower bias. I’m sure, Hugo, with your teams, you make sure that the youngest team members speak first. Not the oldest team members, because it’s easy for people to look at who’s senior and alter their own creative approaches.

Hugo Sarrazin: It’s helpful, at that moment—if someone is asserting a point of view—to ask the question “This was true in what context?” You’re trying to apply something that worked in one context to a different one. That can be deadly if the context has changed, and that’s why organizations struggle to change. You promote all these people because they did something that worked well in the past, and then there’s a disruption in the industry, and they keep doing what got them promoted even though the context has changed.

Simon London: Right. Right.

Hugo Sarrazin: So it’s the same thing in problem solving.

Charles Conn: And it’s why diversity in our teams is so important. It’s one of the best things about the world that we’re in now. We’re likely to have people from different socioeconomic, ethnic, and national backgrounds, each of whom sees problems from a slightly different perspective. It is therefore much more likely that the team will uncover a truly creative and clever approach to problem solving.

Simon London: Let’s move on to step five. You’ve done your work plan. Now you’ve actually got to do the analysis. The thing that strikes me here is that the range of tools that we have at our disposal now, of course, is just huge, particularly with advances in computation, advanced analytics. There’s so many things that you can apply here. Just talk about the analysis stage. How do you pick the right tools?

Charles Conn: For me, the most important thing is that we start with simple heuristics and explanatory statistics before we go off and use the big-gun tools. We need to understand the shape and scope of our problem before we start applying these massive and complex analytical approaches.

Simon London: Would you agree with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: I agree. I think there are so many wonderful heuristics. You need to start there before you go deep into the modeling exercise. There’s an interesting dynamic that’s happening, though. In some cases, for some types of problems, it is even better to set yourself up to maximize your learning. Your problem-solving methodology is test and learn, test and learn, test and learn, and iterate. That is a heuristic in itself, the A/B testing that is used in many parts of the world. So that’s a problem-solving methodology. It’s nothing different. It just uses technology and feedback loops in a fast way. The other one is exploratory data analysis. When you’re dealing with a large-scale problem, and there’s so much data, I can get to the heuristics that Charles was talking about through very clever visualization of data.

You test with your data. You need to set up an environment to do so, but don’t get caught up in neural-network modeling immediately. You’re testing, you’re checking—“Is the data right? Is it sound? Does it make sense?”—before you launch too far.

Simon London: You do hear these ideas—that if you have a big enough data set and enough algorithms, they’re going to find things that you just wouldn’t have spotted, find solutions that maybe you wouldn’t have thought of. Does machine learning sort of revolutionize the problem-solving process? Or are these actually just other tools in the toolbox for structured problem solving?

Charles Conn: It can be revolutionary. There are some areas in which the pattern recognition of large data sets and good algorithms can help us see things that we otherwise couldn’t see. But I do think it’s terribly important we don’t think that this particular technique is a substitute for superb problem solving, starting with good problem definition. Many people use machine learning without understanding algorithms that themselves can have biases built into them. Just as 20 years ago, when we were doing statistical analysis, we knew that we needed good model definition, we still need a good understanding of our algorithms and really good problem definition before we launch off into big data sets and unknown algorithms.

Simon London: Step six. You’ve done your analysis.

Charles Conn: I take six and seven together, and this is the place where young problem solvers often make a mistake. They’ve got their analysis, and they assume that’s the answer, and of course it isn’t the answer. The ability to synthesize the pieces that came out of the analysis and begin to weave those into a story that helps people answer the question “What should I do?” This is back to where we started. If we can’t synthesize, and we can’t tell a story, then our decision maker can’t find the answer to “What should I do?”

Simon London: But, again, these final steps are about motivating people to action, right?

Charles Conn: Yeah.

Simon London: I am slightly torn about the nomenclature of problem solving because it’s on paper, right? Until you motivate people to action, you actually haven’t solved anything.

Charles Conn: I love this question because I think decision-making theory, without a bias to action, is a waste of time. Everything in how I approach this is to help people take action that makes the world better.

Simon London: Hence, these are absolutely critical steps. If you don’t do this well, you’ve just got a bunch of analysis.

Charles Conn: We end up in exactly the same place where we started, which is people speaking across each other, past each other in the public square, rather than actually working together, shoulder to shoulder, to crack these important problems.

Simon London: In the real world, we have a lot of uncertainty—arguably, increasing uncertainty. How do good problem solvers deal with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: At every step of the process. In the problem definition, when you’re defining the context, you need to understand those sources of uncertainty and whether they’re important or not important. It becomes important in the definition of the tree.

You need to think carefully about the branches of the tree that are more certain and less certain as you define them. They don’t have equal weight just because they’ve got equal space on the page. Then, when you’re prioritizing, your prioritization approach may put more emphasis on things that have low probability but huge impact—or, vice versa, may put a lot of priority on things that are very likely and, hopefully, have a reasonable impact. You can introduce that along the way. When you come back to the synthesis, you just need to be nuanced about what you’re understanding, the likelihood.

Often, people lack humility in the way they make their recommendations: “This is the answer.” They’re very precise, and I think we would all be well-served to say, “This is a likely answer under the following sets of conditions” and then make the level of uncertainty clearer, if that is appropriate. It doesn’t mean you’re always in the gray zone; it doesn’t mean you don’t have a point of view. It just means that you can be explicit about the certainty of your answer when you make that recommendation.

Simon London: So it sounds like there is an underlying principle: “Acknowledge and embrace the uncertainty. Don’t pretend that it isn’t there. Be very clear about what the uncertainties are up front, and then build that into every step of the process.”

Hugo Sarrazin: Every step of the process.

Simon London: Yeah. We have just walked through a particular structured methodology for problem solving. But, of course, this is not the only structured methodology for problem solving. One that is also very well-known is design thinking, which comes at things very differently. So, Hugo, I know you have worked with a lot of designers. Just give us a very quick summary. Design thinking—what is it, and how does it relate?

Hugo Sarrazin: It starts with an incredible amount of empathy for the user and uses that to define the problem. It does pause and go out in the wild and spend an enormous amount of time seeing how people interact with objects, seeing the experience they’re getting, seeing the pain points or joy—and uses that to infer and define the problem.

Simon London: Problem definition, but out in the world.

Hugo Sarrazin: With an enormous amount of empathy. There’s a huge emphasis on empathy. Traditional, more classic problem solving is you define the problem based on an understanding of the situation. This one almost presupposes that we don’t know the problem until we go see it. The second thing is you need to come up with multiple scenarios or answers or ideas or concepts, and there’s a lot of divergent thinking initially. That’s slightly different, versus the prioritization, but not for long. Eventually, you need to kind of say, “OK, I’m going to converge again.” Then you go and you bring things back to the customer and get feedback and iterate. Then you rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. There’s a lot of tactile building, along the way, of prototypes and things like that. It’s very iterative.

Simon London: So, Charles, are these complements or are these alternatives?

Charles Conn: I think they’re entirely complementary, and I think Hugo’s description is perfect. When we do problem definition well in classic problem solving, we are demonstrating the kind of empathy, at the very beginning of our problem, that design thinking asks us to approach. When we ideate—and that’s very similar to the disaggregation, prioritization, and work-planning steps—we do precisely the same thing, and often we use contrasting teams, so that we do have divergent thinking. The best teams allow divergent thinking to bump them off whatever their initial biases in problem solving are. For me, design thinking gives us a constant reminder of creativity, empathy, and the tactile nature of problem solving, but it’s absolutely complementary, not alternative.

Simon London: I think, in a world of cross-functional teams, an interesting question is do people with design-thinking backgrounds really work well together with classical problem solvers? How do you make that chemistry happen?

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah, it is not easy when people have spent an enormous amount of time seeped in design thinking or user-centric design, whichever word you want to use. If the person who’s applying classic problem-solving methodology is very rigid and mechanical in the way they’re doing it, there could be an enormous amount of tension. If there’s not clarity in the role and not clarity in the process, I think having the two together can be, sometimes, problematic.

The second thing that happens often is that the artifacts the two methodologies try to gravitate toward can be different. Classic problem solving often gravitates toward a model; design thinking migrates toward a prototype. Rather than writing a big deck with all my supporting evidence, they’ll bring an example, a thing, and that feels different. Then you spend your time differently to achieve those two end products, so that’s another source of friction.

Now, I still think it can be an incredibly powerful thing to have the two—if there are the right people with the right mind-set, if there is a team that is explicit about the roles, if we’re clear about the kind of outcomes we are attempting to bring forward. There’s an enormous amount of collaborativeness and respect.

Simon London: But they have to respect each other’s methodology and be prepared to flex, maybe, a little bit, in how this process is going to work.

Hugo Sarrazin: Absolutely.

Simon London: The other area where, it strikes me, there could be a little bit of a different sort of friction is this whole concept of the day-one answer, which is what we were just talking about in classical problem solving. Now, you know that this is probably not going to be your final answer, but that’s how you begin to structure the problem. Whereas I would imagine your design thinkers—no, they’re going off to do their ethnographic research and get out into the field, potentially for a long time, before they come back with at least an initial hypothesis.

Want better strategies? Become a bulletproof problem solver

Hugo Sarrazin: That is a great callout, and that’s another difference. Designers typically will like to soak into the situation and avoid converging too quickly. There’s optionality and exploring different options. There’s a strong belief that keeps the solution space wide enough that you can come up with more radical ideas. If there’s a large design team or many designers on the team, and you come on Friday and say, “What’s our week-one answer?” they’re going to struggle. They’re not going to be comfortable, naturally, to give that answer. It doesn’t mean they don’t have an answer; it’s just not where they are in their thinking process.

Simon London: I think we are, sadly, out of time for today. But Charles and Hugo, thank you so much.

Charles Conn: It was a pleasure to be here, Simon.

Hugo Sarrazin: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

Simon London: And thanks, as always, to you, our listeners, for tuning into this episode of the McKinsey Podcast . If you want to learn more about problem solving, you can find the book, Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything , online or order it through your local bookstore. To learn more about McKinsey, you can of course find us at McKinsey.com.

Charles Conn is CEO of Oxford Sciences Innovation and an alumnus of McKinsey’s Sydney office. Hugo Sarrazin is a senior partner in the Silicon Valley office, where Simon London, a member of McKinsey Publishing, is also based.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Strategy to beat the odds

Five routes to more innovative problem solving

7 steps of the decision-making process

Reading time: about 4 min

- Identify the decision.

- Gather relevant info.

- Identify the alternatives.

- Weigh the evidence.

- Choose among the alternatives.

- Take action.

- Review your decision.

Robert Frost wrote, “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.” But unfortunately, not every decision is as simple as “Let’s just take this path and see where it goes,” especially when you’re making a decision related to your business.

Whether you manage a small team or are at the head of a large corporation, your success and the success of your company depend on you making the right decisions—and learning from the wrong decisions.

Use these decision-making process steps to help you make more profitable decisions. You'll be able to better prevent hasty decision-making and make more educated decisions.

Defining the business decision-making process

The business decision-making process is a step-by-step process allowing professionals to solve problems by weighing evidence, examining alternatives, and choosing a path from there. This defined process also provides an opportunity, at the end, to review whether the decision was the right one.

7 decision-making process steps

Though there are many slight variations of the decision-making framework floating around on the Internet, in business textbooks, and in leadership presentations, professionals most commonly use these seven steps.

1. Identify the decision

To make a decision, you must first identify the problem you need to solve or the question you need to answer. Clearly define your decision. If you misidentify the problem to solve, or if the problem you’ve chosen is too broad, you’ll knock the decision train off the track before it even leaves the station.

If you need to achieve a specific goal from your decision, make it measurable and timely.

2. Gather relevant information

Once you have identified your decision, it’s time to gather the information relevant to that choice. Do an internal assessment, seeing where your organization has succeeded and failed in areas related to your decision. Also, seek information from external sources, including studies, market research, and, in some cases, evaluation from paid consultants.

Keep in mind, you can become bogged down by too much information and that might only complicate the process.

3. Identify the alternatives

With relevant information now at your fingertips, identify possible solutions to your problem. There is usually more than one option to consider when trying to meet a goal. For example, if your company is trying to gain more engagement on social media, your alternatives could include paid social advertisements, a change in your organic social media strategy, or a combination of the two.

4. Weigh the evidence

Once you have identified multiple alternatives, weigh the evidence for or against said alternatives. See what companies have done in the past to succeed in these areas, and take a good look at your organization’s own wins and losses. Identify potential pitfalls for each of your alternatives, and weigh those against the possible rewards.

5. Choose among alternatives

Here is the part of the decision-making process where you actually make the decision. Hopefully, you’ve identified and clarified what decision needs to be made, gathered all relevant information, and developed and considered the potential paths to take. You should be prepared to choose.

6. Take action

7. review your decision.

After a predetermined amount of time—which you defined in step one of the decision-making process—take an honest look back at your decision. Did you solve the problem? Did you answer the question? Did you meet your goals?

If so, take note of what worked for future reference. If not, learn from your mistakes as you begin the decision-making process again.

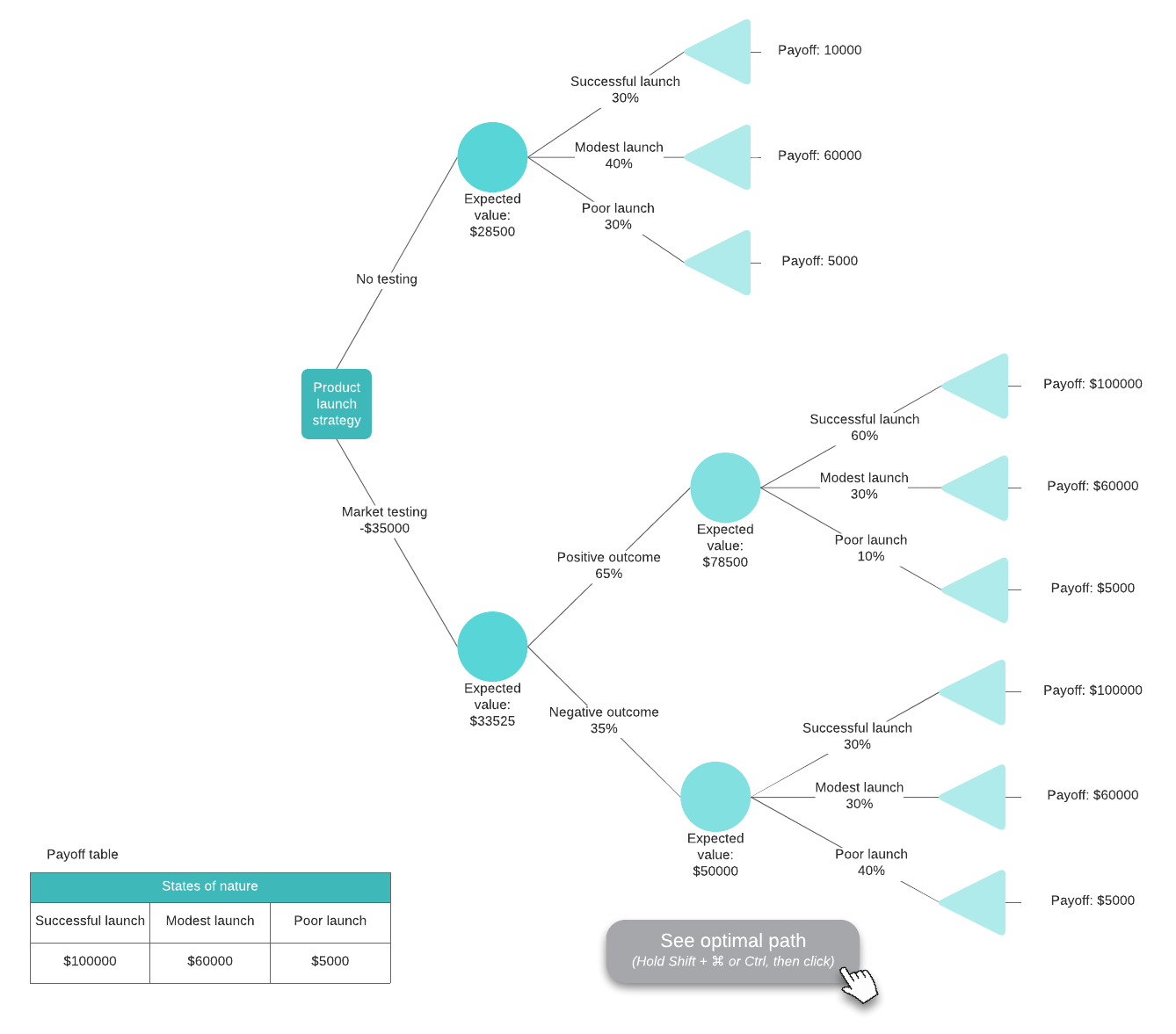

Tools for better decision-making

Depending on the decision, you might want to weigh evidence using a decision tree . The example below shows a company trying to determine whether to perform market testing before a product launch. The different branches record the probability of success and estimated payout so the company can see which option will bring in more revenue.

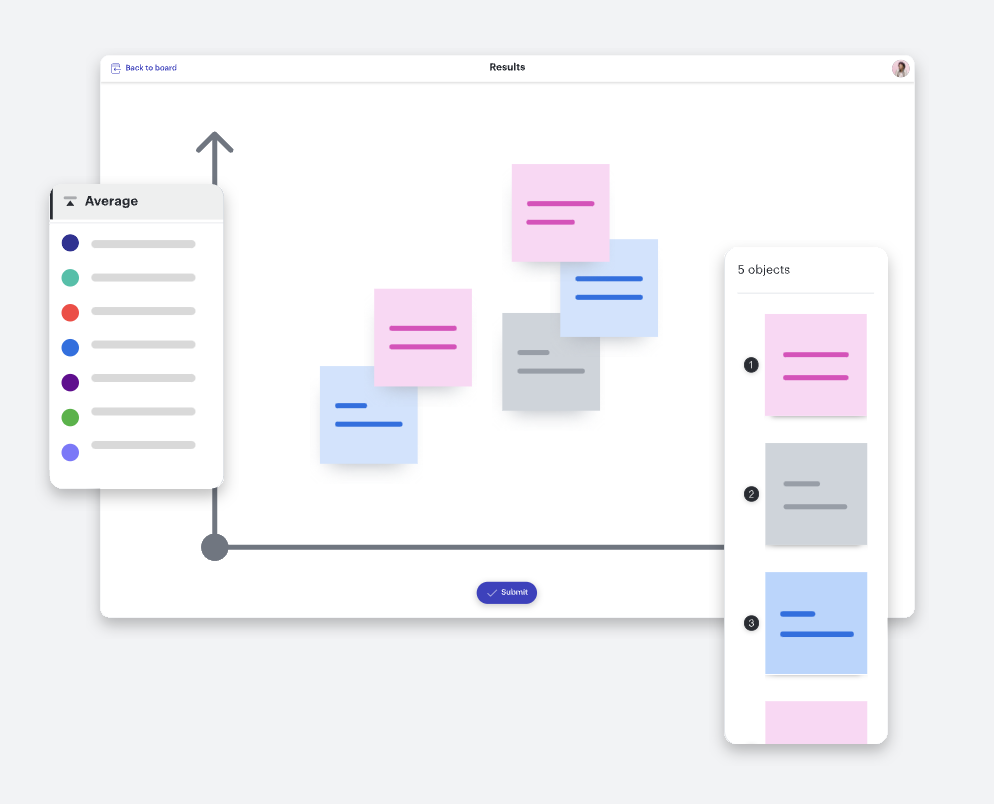

Visual Activities are a perfect choice for quickly synthesizing ideas and gaining consensus. Use these dynamic activities with your team members to turn qualitative feedback into actionable insights and easily make decisions in seconds.

A decision matrix is another tool that can help you evaluate your options and make better decisions. Learn how to make a decision matrix and get started quickly with the template below.

You can also create a classic pros-and-cons list, and clearly highlight whether your options meet necessary criteria or whether they pose too high of a risk.

With these 7 steps we've outlined, plus some tools to get you started, you will be able to make more informed decisions faster .

Explore additional strategies to help with your decision-making process.

About Lucidchart