Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 – Critical Thinking

Since ancient times, the concept of critical thinking has been associated with persuasive communication, usually in the form of speeches, scholarly texts, and literature.

Today, there are many vehicles for information and ideas, but the elements of critical thinking in a university context still bear strong influences from early scholarly writing and oration.

Definition of Critical Thinking

“Critical Thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.”

Source: https://louisville.edu/ideastoaction/about/criticalthinking/what

Critical thinking may seem very abstract in definitions such as the one above, but it is, above all, an action . One source says critical thinking “is about being an active learner rather than a passive recipient of information” ( Skills You Need) Most college curricula are designed to develop critical thinking.

“Critical thinkers rigorously question ideas and assumptions rather than accepting them at face value … They will always seek to determine whether the ideas, arguments, and findings represent the entire picture and are open to the possibility that they do not. It is more than the accumulation of facts, it is a way of thinking.”

( Source: Skills You Need )

In her article, “Why Are Critical Thinking Skills Necessary for Academics?,” journalist Jen Saunders says, “universities concern the ways in which people research and write; their members are responsible for maintaining the foundational principles of truth and knowledge within the folds of scholarship, and permit scholars to grasp and comprehend academic subjects at levels of expertise.” ( https://classroom.synonym.com/ )

Saunders provides this information on the specific ways that critical thinking is important in college-level work:

- Critical thinking supplies the foundation of high-quality academic writing.

- Peer awareness is an element of critical thinking in that it helps students understand and communicate with those who have different experiences, opinions, and perspectives.

- Critical thinking are necessary for passing some exams (e.g., essay answer, a series of multiple-choice questions to test comprehension, and especially situations where students must look for context clues or decipher word elements).

- When students are required to defend a thesis or dissertation, they need to be able to anticipate questions and respond on the spot to those asked by committee members.

Author and master teacher Michael Stratford (Demand Media), in his article, “What Are the Key Ideas for Critical Thinking Skills?”, and the website, Skills You Need, note that someone with critical thinking skills can:

- Interpret data – becoming aware of all of the parts of an argument, such as point of view, audience, and thesis as well as reasoning through moral dilemmas

- Analyze and synthesize – the ability to break down data into individual parts and reassemble them to create something original

- Infer and answer : the ability to explain a problem with an inference, or educated guess. This requires knowing the difference between explaining by inference or by assumptions based on previous ideas

- Make Connections between ideas from varied sources

- Recognize, build, and appraise arguments put forth by others and determine their importance and relevance through objective evaluation

- Spot inconsistencies and errors in reasoning

- Approach problems consistently and systematically

- Reflect on the justification of one’s own assumptions, beliefs, and values

Indeed.com ., a service for finding jobs and polishing a resume, provides the following information about critical thinking. Their website offers five types of skills are important:

Five Important Critical Thinking Skills

Observation.

Observational skills are important for critical thinking because they help you to notice opportunities, problems, and solutions. Eventually, good observers can predict or anticipate problems or issues because their experience widens when they get in the habit of close observation. It is necessary to train yourself to pay close attention to details.

After you have spotted and identified a problem from your observation, your analytical skills become important: You must determine what part of a text or media is important and which parts are not. In other words, gathering and evaluating sources of information that may support or depart from your text or media. This may involve a search for balanced research reports or scholarly work, and asking good questions about the text or media to make sure it is accurate and objective.

Now that you have gathered information or data, you must now interpret it and find a solution or resolution. Even though the information you have may be incomplete, just make an “educated guess,” rather than a quick conclusion. Look for clues (images, symbolism, data charts, or reports) that will help you analyze a situation, so you can evaluate the text or situation and come to a measured conclusion.

COMMUNICATION

In the context of critical thinking, this means engaging or initiating discussions, particularly on difficult issues or questions, especially when you face an audience that you know disagrees with your position. Use your communication skills to persuade them. Active listening, remaining calm, and showing respect are very important elements of communicating with an audience.

PROBLEM SOLVING

The problem-solving part of critical thinking involves applying or executing a conclusion or solution. You will want to choose the best, so this requires a strong understanding of your topic or goal, as well as some idea of how others have handled similar situations.

Essential “Critical” Vocabulary

[Source: ( https://www.espressoenglish.net/difference-between-criticize-criticism-critique-critic-and-critical/]

Now let’s examine the many ways the word “critical” is used in various academic contents. You might be familiar with movie reviews or customer reviews on products in which a critic offers comments. Below are some reviews of a long-standing Chinese restaurant in Columbus, Hunan Lion:

- The restaurant is over priced. You pay for the atmosphere. Ordered the beef and oriental veggies and to be honest it was onions and 3 pieces of broccoli. The meat was fatty and that is the worst. Typically the food is good but last night it wasn’t.

- 35 years of incredible food. By far the best Chinese restaurant in Columbus. If you want to have a great experience, without a doubt go there, you will love it.

- We ordered take out 10/01/2020. Food was TERRIBLE! The Crab Rangoon…well it’s not crab and I’m not sure of the texture it had going on but it was disgusting! The entire order of food after 1 bite went in the trash! I will certainly spread the word DO NOT ORDER FOOD from this restaurant! They are expensive and you are wasting your money. The girl at the cash register surpasses RUDE.

- The food and service were fantastic! We were in on Christmas day, and despite being busy, they did a magnificent job. We will definitely be back!

These reviews were voluntary; nevertheless, the writers of them are considered “critics,” because what they are really offering is judgment.

In a professional or academic setting, critics do much more than give a strong opinion. Whether they offer positive or negative comments, they all try to do so as objectively as possible. In other words, they avoid Personal Bias, meaning they try not to rely exclusively on their personal experiences, but rather they include influences from people, environments, cultures, values, stereotypes, and beliefs.

It is worth noting that all of these influences are part of being human. Part of critical thinking, however, means acknowledging the impact your own biases may have on the questions you ask or your interpreting of material; then, learn to overcome these evaluations. You must be like a judge in a courtroom: you have to try to be fair and leave your own feeling out of the situation.

Activity #1:, inference exercise, harper’s is the oldest general-interest monthly magazine in the u.s. it emphasizes excellent writing and unique and varied perspectives. one of its most celebrated features is the “harper’s index,” which is a collection of random statistics about politics, business, human behavior, social trends, research findings, and so forth. the reader is left alone to make sense of a fact by using inferences and background knowledge., below are some statistics from “harper’s index.” it is up to you to decide what each statistic suggests. something surprising mysterious what could explain its significance.

Choose a few of the facts below and write a response for each in which you raise questions , offer a possible explanation , or propose a tentative theory to explain the fact, or its significance. Consider what the statistic suggests beyond what is written. Your response should be your own opinion , without consulting any internet resources or others.

Example: Percentage increase last year in UFO sightings nationwide: 16% Source: [ July 2021 • Source: National UFO Reporting Center (Davenport,Wash.)] Response: Is this a large or small increase? Maybe the increase is due to the recent U.S. government’s release of a file on unidentified flying objects (UFOs), or, what they call, “Unidentified Aerial Phenomena.” Maybe people feel like they can admit to seeing such phenomena since the government now acknowledges their existence? In the recent past, perhaps people would be laughed at or stigmatized if they claimed to see a UFO because the government and general public believed the idea of “alien life forms” was ridiculous.

Percentage by which the unemployment rate of recently graduated U.S. physics majors exceeds that of art history majors: 60%

Source: November 2020 • Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

ACTIVITY #2 – LINKING FACTS

Sometimes the “Harper’s Index” features pairs of statistics. It is up to you to decide what the pair, seen together, suggests. Select a couple of the pairs below and write down questions you may have, or possible explanations that tell why the pair might be significant. Consider what the statistic suggests beyond what is written. What you write should be your own opinion , without consulting any internet resources or others.

Type your response below each set:

Movie Reviews

One of the most familiar types of criticism we encounter is a movie review, a short description of a film and the reviewer’s opinion about it. When you watch a movie on Netflix, for example, you can see the number of stars (1-5) given by those who have watched and rated the movie. Professional reviewers usually try to give a formal, balanced account of a movie, meaning they usually provide a summary and point out some positive and negative points about a film. Amateur critics, however, can write whatever they like – all positive, all negative, or a combination.

Amateur film critiques can be found in many places; the movie review site, IMDB , is one of the most popular, with a user-generated rating feature. Another popular site is Rotten Tomatoes, which uses a unique ‘tomato meter’ to rate movies: a green tomato means fresh while red means rotten. You can also view the individual ratings given by critics. It has more than 50,000 movies in its database. And finally, another good source of movie reviews is Metacritic , which offers a collection of reviews from various sources.

Let’s look at this review by professional movie critic Roger Ebert ( https://www.rogerebert.com/

In “Top Gun: Maverick,” a sequel to “ Top Gun, ” an admiral refers to navy aviator Pete Mitchell (Tom Cruise)—call sign “ Maverick ”—as “the fastest man alive.” Truth be told, our fearless and ever-handsome action hero earns both appraisals and applause. Indeed, Cruise’s consistent commitment to Hollywood showmanship deserves the same level of respect usually reserved for the fully-method actors such as Daniel Day-Lewis . Even if you somehow overlook the fact that Cruise is one of our most gifted and versatile dramatic and comedic actors with movies like “ Mission Impossible , ” “ Born on the Fourth of July ,” “ Magnolia ,” “ Tropic Thunder ,” and “ Collateral ” on his CV, you will never forget why you show up to a Tom Cruise movie.

Director Joseph Kosinski allows the leading actor to be exactly what he is—a star—while upping the emotional and dramatic stakes of the first Top Gun (1986) with a healthy dose of nostalgia. In this Top Gun sequel, we find Maverick in a role on the fringes of the US Navy, working as a test pilot. You won’t be surprised that soon enough, he gets called on a one-last-job type of mission as a teacher to a group of recent training graduates. Their assignment is just as obscure and politically cuckoo as it was in the first movie. There is an unnamed enemy—let’s called it Russia because it’s probably Russia—some targets that need to be destroyed, a flight plan that sounds nuts, and a scheme that will require all successful Top Gun recruits to fly at dangerously low altitudes. But can it be done?

In a different package, all the proud fist-shaking seen in “Top Gun: Maverick” could have been borderline insufferable, but fortunately Kosinski seems to understand exactly what kind of movie he is asked to navigate. In his hands, the tone of “Maverick” strikes a fine balance between good-humored vanity and half-serious self-deprecation, complete with plenty of emotional moments that catch one off-guard.

In some sense, what this movie takes most seriously are concepts like friendship, loyalty, romance, and okay, bromance. Still, the action sequences are likewise the breathtaking stars of “Maverick.” Reportedly, all the flying scenes were shot in actual U.S. Navy F/A-18s, for which the cast had to be trained. Equally worthy of that big screen is the emotional strokes of “Maverick” that pack an unexpected punch. Sure, you might be prepared for a second sky-dance with “Maverick,” but perhaps not one that might require a tissue or two in its final stretch.

Available in theaters May 27th, 2022

ACTIVITY #3 – BEING A CRITIC

Analyze the film review above. Does the reviewer give the movie a strongly positive or negative review? A mildly positive or negative review? A balanced review? How can you tell? Support your opinion by identifying words, phases, and/or comparisons that directly or indirectly are positive, negative, or neutral.

ACTIVITY #4 – WRITE A MOVIE REVIEW

Select a movie to review. Choose one you either love or hate. (If it evokes emotions, it’s usually easier to review.) You may choose any movie, but for this assignment, don’t choose a film that might upset your target audience – your instructor and classmates. A movie review can be long or short. Usually a simple outline of the plot and a sentence or two about the general setting in which it takes place will be sufficient, then add your opinion and analysis. The opinion section should be the main focus of your review. Don’t get too detailed. Your instructor will determine the word limit of this assignment.

Suggestions:

Do a web search to find information about the film: is it based on real-life events or is it fiction?

Find some information about the director and his/her/their style.

Look for information about the cast, the budget, the filming location, and where the idea for the film’s story came from. In other words, why did the producers want to make the movie?

Be sure to keep notes on where you find each piece of information – its source. Most of the facts about movies are considered common knowledge, so they don’t have to be included in your review.

Avoid reading other reviews. They might influence your opinion, and that kind of information needs to be cited in a review.

When you are watching the film make notes of important scenes or details, symbolism, or the performances of the characters. You may want to analyze these in detail later. Again, keep notes on the source of the information you find.

Don’t give away the ending! Remember, reviews help readers decide whether or not to watch the movie. No spoilers!

Suggested Steps:

Write an introduction where you include all the basic information so that the film can be easily identified. Note the name, the director, main cast, and the characters in the story, along with the year it was made. Briefly provide the main idea of the film.

Write the main body. Analyze the story, the acting, and the director’s style. Discuss anything you would have done differently, a technique that was successful, or dialogue that was important. In other words, here is where you convey your opinion and the reasons for it. You may choose to analyze in detail one scene from the film that made an impression on you, or you may focus on an actor’s performance, or the film’s setting, music, light, character development, or dialogu

Make a conclusion. Search for several reviews of the film. Include how the film was rated by others. You will need to include information about where you found the information. Then, give your own opinion and your recommendation. You can end with a reason the audience might enjoy it or a reason you do not recommend it. Include a summary of the reasons you recommend or do not recommend it.

[Source: https://academichelp.net/academic-assignments/review/write-film-review.html]

————————————————

References:

10 Top Critical Thinking Skills (and how to improve them).(2022). Indeed.com: https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/critical-thinking-skills

Difference between criticize, criticism, critique, critic, and critical. Espresso English : https://www.espressoenglish.net/difference-between-criticize-criticism-critique-critic-and-critical/

Hansen, R.S. (n.d.). Ways in which college is different from high school. My CollegeSuccessStory.com .

Ideas to Action. Critical Thinking Inventories. University of Louisville: https:// louisville.edu/ideastoaction/about/criticalthinking/what

Saunders, J. (n.d.). “Why Are Critical Thinking Skills Necessary for Academics?,” Demand Media.

Stratford, M. (n.d. ) What are the key ideas for critical thinking skills? Demand Media .

Van Zyl, M.A., Bays, C.L., & Gilchrist, C. (2013). Assessing teaching critical thinking with validated critical thinking inventories: The learning critical thinking inventory (LCTI) and the teaching critical thinking inventory (TCTI). Inquiry: Critical Thinking Across The Discipline , 28(3), 40-50.

What is Critical Thinking? (n.d.). Skills You Need : https://www.skillsyouneed.com/learn/critical-thinking.html

Write a Film Review. Academic Help: Write Better : https://academichelp.net/academic-assignments/review/write-film-review.html

Critical Reading, Writing, and Thinking Copyright © 2022 by Zhenjie Weng, Josh Burlile, Karen Macbeth is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Module 1: Success Skills

Critical thinking, introduction, learning objectives.

- define critical thinking

- identify the role that logic plays in critical thinking

- apply critical thinking skills to problem-solving scenarios

- apply critical thinking skills to evaluation of information

Consider these thoughts about the critical thinking process, and how it applies not just to our school lives but also our personal and professional lives.

“Thinking Critically and Creatively”

Critical thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. You use them every day, and you can continue improving them.

The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking.

The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze myriad issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information?

It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners and researchers.

—Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom

Defining Critical Thinking

Thinking comes naturally. You don’t have to make it happen—it just does. But you can make it happen in different ways. For example, you can think positively or negatively. You can think with “heart” and you can think with rational judgment. You can also think strategically and analytically, and mathematically and scientifically. These are a few of multiple ways in which the mind can process thought.

What are some forms of thinking you use? When do you use them, and why?

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important of these skills is critical thinking. Critical thinking is important because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It’s not restricted to a particular subject area.

Critical thinking is clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do. It means asking probing questions like, “How do we know?” or “Is this true in every case or just in this instance?” It involves being skeptical and challenging assumptions, rather than simply memorizing facts or blindly accepting what you hear or read.

Imagine, for example, that you’re reading a history textbook. You wonder who wrote it and why, because you detect certain assumptions in the writing. You find that the author has a limited scope of research focused only on a particular group within a population. In this case, your critical thinking reveals that there are “other sides to the story.”

Who are critical thinkers, and what characteristics do they have in common? Critical thinkers are usually curious and reflective people. They like to explore and probe new areas and seek knowledge, clarification, and new solutions. They ask pertinent questions, evaluate statements and arguments, and they distinguish between facts and opinion. They are also willing to examine their own beliefs, possessing a manner of humility that allows them to admit lack of knowledge or understanding when needed. They are open to changing their mind. Perhaps most of all, they actively enjoy learning, and seeking new knowledge is a lifelong pursuit.

This may well be you!

No matter where you are on the road to being a critical thinker, you can always more fully develop your skills. Doing so will help you develop more balanced arguments, express yourself clearly, read critically, and absorb important information efficiently. Critical thinking skills will help you in any profession or any circumstance of life, from science to art to business to teaching.

Critical Thinking in Action

The following video, from Lawrence Bland, presents the major concepts and benefits of critical thinking.

Critical Thinking and Logic

Critical thinking is fundamentally a process of questioning information and data. You may question the information you read in a textbook, or you may question what a politician or a professor or a classmate says. You can also question a commonly-held belief or a new idea. With critical thinking, anything and everything is subject to question and examination.

Logic’s Relationship to Critical Thinking

The word logic comes from the Ancient Greek logike , referring to the science or art of reasoning. Using logic, a person evaluates arguments and strives to distinguish between good and bad reasoning, or between truth and falsehood. Using logic, you can evaluate ideas or claims people make, make good decisions, and form sound beliefs about the world. [1]

Questions of Logic in Critical Thinking

Let’s use a simple example of applying logic to a critical-thinking situation. In this hypothetical scenario, a man has a PhD in political science, and he works as a professor at a local college. His wife works at the college, too. They have three young children in the local school system, and their family is well known in the community.

The man is now running for political office. Are his credentials and experience sufficient for entering public office? Will he be effective in the political office? Some voters might believe that his personal life and current job, on the surface, suggest he will do well in the position, and they will vote for him.

In truth, the characteristics described don’t guarantee that the man will do a good job. The information is somewhat irrelevant. What else might you want to know? How about whether the man had already held a political office and done a good job? In this case, we want to ask, How much information is adequate in order to make a decision based on logic instead of assumptions?

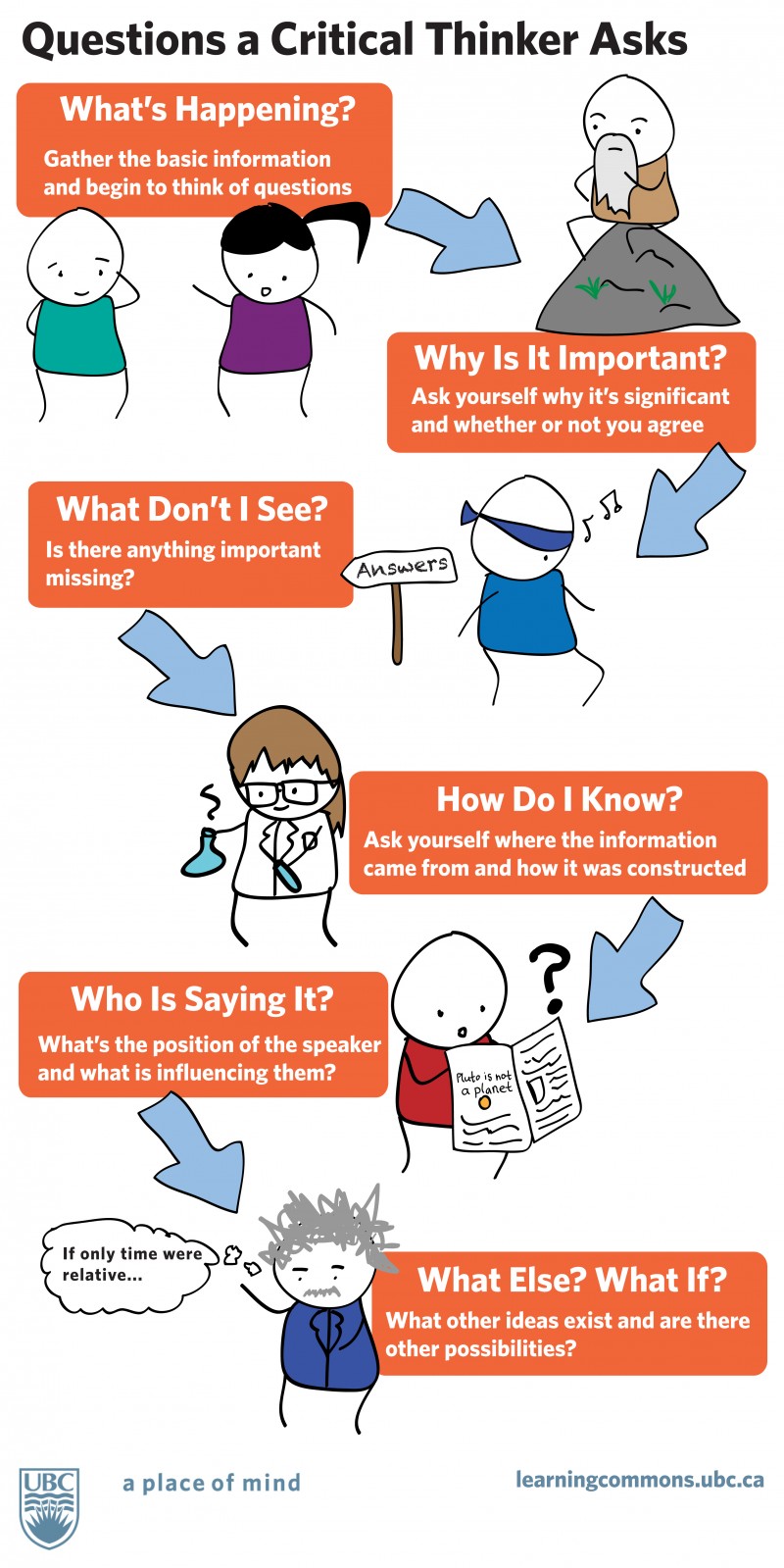

The following questions, presented in Figure 1, below, are ones you may apply to formulating a logical, reasoned perspective in the above scenario or any other situation:

- What’s happening? Gather the basic information and begin to think of questions.

- Why is it important? Ask yourself why it’s significant and whether or not you agree.

- What don’t I see? Is there anything important missing?

- How do I know? Ask yourself where the information came from and how it was constructed.

- Who is saying it? What’s the position of the speaker and what is influencing them?

- What else? What if? What other ideas exist and are there other possibilities?

Problem-Solving With Critical Thinking

For most people, a typical day is filled with critical thinking and problem-solving challenges. In fact, critical thinking and problem-solving go hand-in-hand. They both refer to using knowledge, facts, and data to solve problems effectively. But with problem-solving, you are specifically identifying, selecting, and defending your solution. Below are some examples of using critical thinking to problem-solve:

- Your roommate was upset and said some unkind words to you, which put a crimp in your relationship. You try to see through the angry behaviors to determine how you might best support your roommate and help bring your relationship back to a comfortable spot.

- Your final art class project challenges you to conceptualize form in new ways. On the last day of class when students present their projects, you describe the techniques you used to fulfill the assignment. You explain why and how you selected that approach.

- Your math teacher sees that the class is not quite grasping a concept. She uses clever questioning to dispel anxiety and guide you to new understanding of the concept.

- You have a job interview for a position that you feel you are only partially qualified for, although you really want the job and you are excited about the prospects. You analyze how you will explain your skills and experiences in a way to show that you are a good match for the prospective employer.

- You are doing well in college, and most of your college and living expenses are covered. But there are some gaps between what you want and what you feel you can afford. You analyze your income, savings, and budget to better calculate what you will need to stay in college and maintain your desired level of spending.

Problem-Solving Action Checklist

Problem-solving can be an efficient and rewarding process, especially if you are organized and mindful of critical steps and strategies. Remember, too, to assume the attributes of a good critical thinker. If you are curious, reflective, knowledge-seeking, open to change, probing, organized, and ethical, your challenge or problem will be less of a hurdle, and you’ll be in a good position to find intelligent solutions.

Evaluating Information With Critical Thinking

Evaluating information can be one of the most complex tasks you will be faced with in college. But if you utilize the following four strategies, you will be well on your way to success:

- Read for understanding by using text coding

- Examine arguments

- Clarify thinking

1. Read for Understanding Using Text Coding

When you read and take notes, use the text coding strategy . Text coding is a way of tracking your thinking while reading. It entails marking the text and recording what you are thinking either in the margins or perhaps on Post-it notes. As you make connections and ask questions in response to what you read, you monitor your comprehension and enhance your long-term understanding of the material.

With text coding, mark important arguments and key facts. Indicate where you agree and disagree or have further questions. You don’t necessarily need to read every word, but make sure you understand the concepts or the intentions behind what is written. Feel free to develop your own shorthand style when reading or taking notes. The following are a few options to consider using while coding text.

See more text coding from PBWorks and Collaborative for Teaching and Learning .

2. Examine Arguments

When you examine arguments or claims that an author, speaker, or other source is making, your goal is to identify and examine the hard facts. You can use the spectrum of authority strategy for this purpose. The spectrum of authority strategy assists you in identifying the “hot” end of an argument—feelings, beliefs, cultural influences, and societal influences—and the “cold” end of an argument—scientific influences. The following video explains this strategy.

3. Clarify Thinking

When you use critical thinking to evaluate information, you need to clarify your thinking to yourself and likely to others. Doing this well is mainly a process of asking and answering probing questions, such as the logic questions discussed earlier. Design your questions to fit your needs, but be sure to cover adequate ground. What is the purpose? What question are we trying to answer? What point of view is being expressed? What assumptions are we or others making? What are the facts and data we know, and how do we know them? What are the concepts we’re working with? What are the conclusions, and do they make sense? What are the implications?

4. Cultivate “Habits of Mind”

“Habits of mind” are the personal commitments, values, and standards you have about the principle of good thinking. Consider your intellectual commitments, values, and standards. Do you approach problems with an open mind, a respect for truth, and an inquiring attitude? Some good habits to have when thinking critically are being receptive to having your opinions changed, having respect for others, being independent and not accepting something is true until you’ve had the time to examine the available evidence, being fair-minded, having respect for a reason, having an inquiring mind, not making assumptions, and always, especially, questioning your own conclusions—in other words, developing an intellectual work ethic. Try to work these qualities into your daily life.

Candela Citations

- Outcome: Critical Thinking. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Self Check: Critical Thinking. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Foundations of Academic Success. Authored by : Thomas C. Priester, editor. Provided by : Open SUNY Textbooks. Located at : http://textbooks.opensuny.org/foundations-of-academic-success/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of woman thinking. Authored by : Moyan Brenn. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/8YV4K5 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : Critical and Creative Thinking Program. Located at : http://cct.wikispaces.umb.edu/Critical+Thinking . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking Skills. Authored by : Linda Bruce. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Project : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/lumencollegesuccess/chapter/critical-thinking-skills/. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of critical thinking poster. Authored by : Melissa Robison. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/bwAzyD . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Thinking Critically. Authored by : UBC Learning Commons. Provided by : The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Campus. Located at : http://www.oercommons.org/courses/learning-toolkit-critical-thinking/view . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking 101: Spectrum of Authority. Authored by : UBC Leap. Located at : https://youtu.be/9G5xooMN2_c . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of students putting post-its on wall. Authored by : Hector Alejandro. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/7b2Ax2 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of man thinking. Authored by : Chad Santos. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/phLKY . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking.wmv. Authored by : Lawrence Bland. Located at : https://youtu.be/WiSklIGUblo . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- "logic." Wordnik . n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016 . ↵

- "Student Success-Thinking Critically In Class and Online." Critical Thinking Gateway . St Petersburg College, n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵