Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 03 October 2022

How COVID-19 shaped mental health: from infection to pandemic effects

- Brenda W. J. H. Penninx ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7779-9672 1 , 2 ,

- Michael E. Benros ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4939-9465 3 , 4 ,

- Robyn S. Klein 5 &

- Christiaan H. Vinkers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3698-0744 1 , 2

Nature Medicine volume 28 , pages 2027–2037 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

46k Accesses

192 Citations

484 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Infectious diseases

- Neurological manifestations

- Psychiatric disorders

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has threatened global mental health, both indirectly via disruptive societal changes and directly via neuropsychiatric sequelae after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Despite a small increase in self-reported mental health problems, this has (so far) not translated into objectively measurable increased rates of mental disorders, self-harm or suicide rates at the population level. This could suggest effective resilience and adaptation, but there is substantial heterogeneity among subgroups, and time-lag effects may also exist. With regard to COVID-19 itself, both acute and post-acute neuropsychiatric sequelae have become apparent, with high prevalence of fatigue, cognitive impairments and anxiety and depressive symptoms, even months after infection. To understand how COVID-19 continues to shape mental health in the longer term, fine-grained, well-controlled longitudinal data at the (neuro)biological, individual and societal levels remain essential. For future pandemics, policymakers and clinicians should prioritize mental health from the outset to identify and protect those at risk and promote long-term resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

A longitudinal analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of middle-aged and older adults from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging

Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and carer mental health: an international multicentre study

In 2019, the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), with 590 million confirmed cases and 6.4 million deaths worldwide as of August 2022 (ref. 1 ). To contain the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) across the globe, many national and local governments implemented often drastic restrictions as preventive health measures. Consequently, the pandemic has not only led to potential SARS-CoV-2 exposure, infection and disease but also to a wide range of policies consisting of mask requirements, quarantines, lockdowns, physical distancing and closure of non-essential services, with unprecedented societal and economic consequences.

As the world is slowly gaining control over COVID-19, it is timely and essential to ask how the pandemic has affected global mental health. Indirect effects include stress-evoking and disruptive societal changes, which may detrimentally affect mental health in the general population. Direct effects include SARS-CoV-2-mediated acute and long-lasting neuropsychiatric sequelae in affected individuals that occur during primary infection or as part of post-acute COVID syndrome (PACS) 2 —defined as symptoms lasting beyond 3–4 weeks that can involve multiple organs, including the brain. Several terminologies exist for characterizing the effects of COVID-19. PACS also includes late sequalae that constitute a clinical diagnosis of ‘long COVID’ where persistent symptoms are still present 12 weeks after initial infection and cannot be attributed to other conditions 3 .

Here we review both the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on mental health. First, we summarize empirical findings on how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted population mental health, through mental health symptom reports, mental disorder prevalence and suicide rates. Second, we describe mental health sequalae of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection and COVID-19 disease (for example, cognitive impairment, fatigue and affective symptoms). For this, we use the term PACS for neuropsychiatric consequences beyond the acute period, and will also describe the underlying neurobiological impact on brain structure and function. We conclude with a discussion of the lessons learned and knowledge gaps that need to be further addressed.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on population mental health

Independent of the pandemic, mental disorders are known to be prevalent globally and cause a very high disease burden 4 , 5 , 6 . For most common mental disorders (including major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorder), environmental stressors play a major etiological role. Disruptive and unpredictable pandemic circumstances may increase distress levels in many individuals, at least temporarily. However, it should be noted that the pandemic not only resulted in negative stressors but also in positive and potentially buffering changes for some, including a better work–life balance, improved family dynamics and enhanced feelings of closeness 7 .

Awareness of the potential mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is reflected in the more than 35,000 papers published on this topic. However, this rapid research output comes with a cost: conclusions from many papers are limited due to small sample sizes, convenience sampling with unclear generalizability implications and lack of a pre-COVID-19 comparison. More reliable estimates of the pandemic mental health impact come from studies with longitudinal or time-series designs that include a pre-pandemic comparison. In our description of the evidence, we, therefore, explicitly focused on findings from meta-analyses that include longitudinal studies with data before the pandemic, as recently identified through a systematic literature search by the WHO 8 .

Self-reported mental health problems

Most studies examining the pandemic impact on mental health used online data collection methods to measure self-reported common indicators, such as mood, anxiety or general psychological distress. Pooled prevalence estimates of clinically relevant high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic range widely—between 20% and 35% 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 —but are difficult to interpret due to large methodological and sample heterogeneity. It also is important to note that high levels of self-reported mental health problems identify increased vulnerability and signal an increased risk for mental disorders, but they do not equal clinical caseness levels, which are generally much lower.

Three meta-analyses, pooling data from between 11 and 61 studies and involving ~50,000 individuals or more 13 , 14 , 15 , compared levels of self-reported mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic with those before the pandemic. Meta-analyses report on pooled effect sizes—that is, weighted averages of study-level effect sizes; these are generally considered small when they are ~0.2, moderate when ~0.5 and large when ~0.8. As shown in Table 1 , meta-analyses on mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic reach consistent conclusions and indicate that there has been a heterogeneous, statistically significant but small increase in self-reported mental health problems, with pooled effect sizes ranging from 0.07 to 0.27. The largest symptom increase was found when using specific mental health outcome measures assessing depression or anxiety symptoms. In addition, loneliness—a strong correlate of depression and anxiety—showed a small but significant increase during the pandemic (Table 1 ; effect size = 0.27) 16 . In contrast, self-reported general mental health and well-being indicators did not show significant change, and psychotic symptoms seemed to have decreased slightly 13 . In Europe, alcohol purchase decreased, but high-level drinking patterns solidified among those with pre-pandemic high drinking levels 17 . When compared to pre-COVID levels, no change in self-reported alcohol use (effect size = −0.01) was observed in a recent meta-analysis summarizing 128 studies from 58 (predominantly European and North American) countries 18 .

What is the time trajectory of self-reported mental health problems during the pandemic? Although findings are not uniform, various large-scale studies confirmed that the increase in mental health problems was highest during the first peak months of the pandemic and smaller—but not fully gone—in subsequent months when infection rates declined and social restrictions eased 13 , 19 , 20 . Psychological distress reports in the United Kingdom increased again during the second lockdown period 15 . Direct associations between anxiety and depression symptom levels and the average number of daily COVID-19 cases were confirmed in the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data 21 . Studies that examined longer-term trajectories of symptoms during the first or even second year of the COVID-19 pandemic are more sparse but revealed stability of symptoms without clear evidence of recovery 15 , 22 . The exception appears to be for loneliness, as some studies confirmed further increasing trends throughout the first COVID-19 pandemic year 22 , 23 . As most published population-based studies were conducted in the early time period in which absolute numbers of SARS-CoV2-infected individuals were still low, the mental health impacts described in such studies are most likely due to indirect rather than direct effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, it is possible that, in longer-term or later studies, these direct and indirect effects may be more intertwined.

The extent to which governmental policies and communication have impacted on population mental health is a relevant question. In cross-country comparisons, the extent of social restrictions showed a dose–response relationship with mental health problems 24 , 25 . In a review of 33 studies worldwide, it was concluded that governments that enacted stringent measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 benefitted not only the physical but also the mental health of their population during the pandemic 26 , even though more stringent policies may lead to more short-term mental distress 25 . It has been suggested that effective communication of risks, choices and policy measures may reduce polarization and conspiracy theories and mitigate the mental health impact of such measures 25 , 27 , 28 .

In sum, the general pattern of results is that of an increase in mental health symptoms in the population, especially during the first pandemic months, that remained elevated throughout 2020 and early 2021. It should be emphasized that this increase has a small effect size. However, even a small upward shift in mental health problems warrants attention as it has not yet shown to be returned to pre-pandemic levels, and it may have meaningful cumulative consequences at the population level. In addition, even a small effect size may mask a substantial heterogeneity in mental health impact, which may have affected vulnerable groups disproportionally (see below).

Mental disorders, self-harm and suicide

Whether the observed increase in mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic has translated into more mental disorders or even suicide mortality is not easy to answer. Mental disorders, characterized by more severe, disabling and persistent symptoms than self-reported mental health problems, are usually diagnosed by a clinician based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) criteria or with validated semi-structured clinical interviews. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, research systematically examining the population prevalence of mental disorders has been sparse. Unfortunately, we can also not strongly rely on healthcare use studies as the pandemic impacted on healthcare provision more broadly, thereby making figures of patient admissions difficult to interpret.

On a global scale and based on imputations and modeling from survey data of self-reported mental health problems, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 29 estimated that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a 28% (95% uncertainty interval (UI): 25–30) increase in major depressive disorders and a 26% (95% UI: 23–28) increase in anxiety disorders. It should be noted that these estimations come with high uncertainty as the assumption that transient pandemic-related increases in mental symptoms extrapolate into incident mental disorders remains disputable. So far, only four longitudinal population-based studies have measured and compared current mental (that is, depressive and anxiety) disorder prevalence—defined using psychiatric diagnostic criteria—before and during the pandemic. Of these, two found no change 30 , 31 , one found a decrease 32 and one found an increase in prevalence of these disorders 33 . These studies were local, limited to high-income countries, often small-scale and used different modes of assessment (for example, online versus in-person) before and during the pandemic. This renders these observational results uncertain as well, but their contrast to the GBD calculations 29 is striking.

Time-series analysis of monthly suicide trends in 21 middle-income to high-income countries across the globe yielded no evidence for an increase in suicide rates in the first 4 months of the pandemic, and there was evidence of a fall in rates in 12 countries 34 . Also in the United States, there was a significant decrease in suicide mortality in the first pandemic months but a slight increase in mortality due to drug overdose and homicide 35 . A living systematic review 36 also concluded that, throughout 2020, there was no observed increase in suicide rates in 20 studies conducted in North America, Europe and Asia. Analyses of electronic health record data in the primary care setting showed reduced rates of self-harm during the first COVID-19 pandemic year 37 . In contrast, emergency department visits for self-harm behavior were unchanged 38 or increased 39 . Such inconsistent findings across healthcare settings may reflect a reluctance in healthcare-seeking behavior for mental healthcare issues. In the living systematic review, eight of 11 studies that examined service use data found a significant decrease in reported self-harm/suicide attempts after COVID lockdown, which returned to pre-lockdown levels in some studies with longer follow-up (5 months) 36 .

In sum, although calculations based on survey data predict a global increase of mental disorder prevalence, objective and consistent evidence for an increased mental disorder, self-harm or suicide prevalence or incidence during the first pandemic year remains absent. This observation, coupled with the only small increase in mental health symptom levels in the overall population, may suggest that most of the general population has demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptation. However, alternative interpretations are possible. First, there is a large degree of heterogeneity in the mental health impact of COVID-19, and increased mental health in one group (for example, due to better work–family balance and work flexibility) may have masked mental health problems in others. Various societal responses seen in many countries, such as community support activities and bolstering mental health and crisis services, may have had mitigating effects on the mental health burden. Also, the relationship between mental health symptom increases during stressful periods and its subsequent effects on the incidence of mental disorders may be non-linear or could be less visible due to resulting alternative outcomes, such as drug overdose or homicide. Finally, we cannot rule out a lag-time effect, where disorders may take more time to develop or be picked up, especially because some of the personal financial or social consequences of the COVID pandemic may only become apparent later. It should be noted that data from low-income countries and longer-term studies beyond the first pandemic year are largely absent.

Which individuals are most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic?

There is substantial heterogeneity across studies that evaluated how the COVID pandemic impacted on mental health 13 , 14 , 15 . Although our society as a whole may have the ability to adequately bounce back from pandemic effects, there are vulnerable people who have been affected more than others.

First, women have consistently reported larger increases in mental health problems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic than men 13 , 15 , 29 , 40 , with meta-analytic effect sizes being 44% 15 to 75% 13 higher. This could reflect both higher stress vulnerability or larger daily life disruptions due to, for example, increased childcare responsibilities, exposure to home violence or greater economic impact due to employment disruptions that all disproportionately fell to women 41 , thereby exacerbating the already existing pre-pandemic gender inequalities in depression and anxiety levels. In addition, adolescents and young adults have been disproportionately affected compared to younger children and older adults 12 , 15 , 29 , 40 . This may be the result of unfavorable behavioral and social changes (for example, school closure periods 42 ) during a crucial development phase where social interactions outside the family context are pivotal. Alarmingly, even though suicide rates did not seem to increase at the population level, studies in China 43 and Japan 44 indicated significant increases in suicide rates in children and adolescents.

Existing socio-cultural disparities in mental health may have further widened during the COVID pandemic. Whether the impact is larger for individuals with low socio-economic status remains unclear, with contrasting meta-analyses pointing toward this group being protected 15 or at increased risk 40 . Earlier meta-analyses did not find that the mental health impact of COVID-19 differed across Europe, North America, Asia and Oceania 13 , 14 , but data are lacking from Africa and South America. Nevertheless, a large-scale within-country comparison in the United States found that the mental health of Black, Hispanic and Asian respondents worsened relatively more during the pandemic compared to White respondents. Moreover, White respondents were more likely to receive professional mental healthcare during the pandemic, and, conversely, Black, Hispanic, and Asian respondents demonstrated higher levels of unmet mental healthcare needs during this time 45 .

People with pre-existing somatic conditions represent another vulnerable group in which the pandemic had a greater impact (pooled effect size of 0.25) 13 . This includes people with conditions such as epilepsy, multiple sclerosis or cardiometabolic disease as well as those with multiple comorbidities. The disproportionate impact may reflect this groupʼs elevated COVID-19 risk and, consequently, more perceived stress and fear of infection, but it could also reflect disruptions of regular healthcare services.

Healthcare workers faced increased workload, rapidly changing and challenging work environments and exposure to infections and death, accompanied by fear of infecting themselves and their families. High prevalences of (subthreshold) depression (13% 46 ), depressive symptoms (31% 47 ), (subthreshold) anxiety (16% 46 ), anxiety symptoms (23% 47 ) and post-traumatic stress disorder (~22% 46 , 47 ) have been reported in healthcare workers. However, a meta-analysis did not find a larger mental health impact of the pandemic as compared to the general population 40 , and another meta-analysis (of 206 studies) found that the mental health status of healthcare workers was similar to or even better than that of the general population during the first COVID year 48 . However, it is important to note that these meta-analyses could not differentiate between frontline and non-frontline healthcare workers.

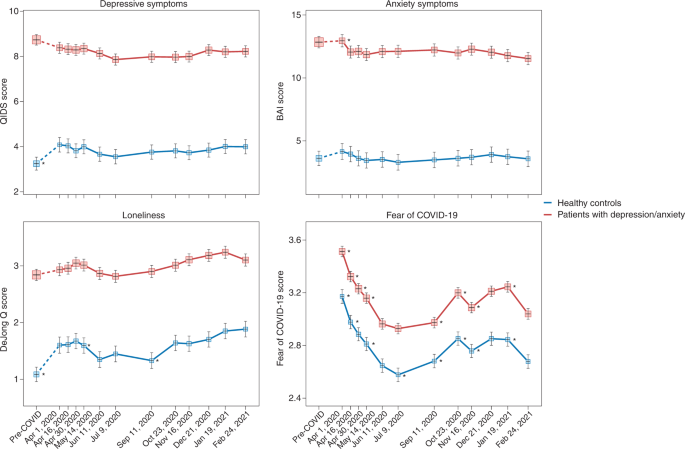

Finally, individuals with pre-existing mental disorders may be at increased risk for exacerbation of mental ill-health during the pandemic, possibly due to disease history—illustrating a higher genetic and/or environmental vulnerability—but also due to discontinuity of mental healthcare. Already before the pandemic, mental health systems were under-resourced and disorganized in most countries 6 , 49 , but a third of all WHO member states reported disruptions to mental and substance use services during the first 18 months of the pandemic 50 , with reduced, shortened or postponed appointments and limited capacity for acute inpatient admissions 51 , 52 . Despite this, there is no clear evidence that individuals with pre-existing mental disorders are disproportionately affected by pandemic-related societal disruptions; the effect size for pandemic impact on self-reported mental health problems was similar in psychiatric patients and the general population 13 . In the United States, emergency visits for ten different mental disorders were generally stable during the pandemic compared to earlier periods 53 . In a large Dutch study 22 , 54 with multiple pre-pandemic and during-pandemic assessments, there was no difference in symptom increase among patients relative to controls (see Fig. 1 for illustration). In absolute terms, however, it is important to note that psychiatric patients show much higher symptom levels of depression, anxiety, loneliness and COVID-fear than healthy controls. Again, variation in mental health changes during the pandemic is large: next to psychiatric patients who showed symptom decrease due to, for example, experiencing relief from social pressures, there certainly have been many patients with symptom increases and relapses during the pandemic.

Trajectories of mean depressive symptoms (QIDS score), anxiety symptoms (BAI score), loneliness (De Jong questionnaire score) and Fear of COVID-19 score before and during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in healthy controls (blue line, n = 378) and in patients with depressive and/or anxiety disorders (red line, n = 908). The x -axis indicates time with one pre-COVID assessment (averaged over up to five earlier assessments conducted between 2006 and 2019) and 11 online assessments during April 2020 through February 2021. Symbols indicate the mean score during the assessment with 95% CIs. As compared to pre-COVID assessment scores, the figure shows a statistically significant increase of depression and loneliness symptoms during the first pandemic peak (April 2020) in healthy controls but not in patients (for more details, see refs. 22 , 54 ). Asterisks indicate where subsequent wave scores differ from the prior wave scores ( P < 0.05). The figure also illustrates the stability of depressive and anxiety symptoms during the first COVID year, a significant increase in loneliness during this period and fluctuations of Fear of COVID-19 score that positively correlate with infection rates in the Netherlands. Raw data are from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), which were re-analyzed for the current plots to illustrate differences between two groups (healthy controls versus patients). BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; QIDS, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms.

Impact of COVID-19 infection and disease on mental health and the brain

Not only the pandemic but also COVID-19 itself can have severe impact on the mental health of affected individuals and, thus, of the population at large. Below we describe acute and post-acute neuropsychiatric sequelae seen in patients with COVID-19 and link these to neurobiological mechanisms.

Neuropsychiatric sequelae in individuals with COVID-19

Common symptoms associated with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection include headache, anosmia (loss of sense of smell) and dysgeusia (loss of sense of taste). The broader neuropsychiatric impact is dependent on infection severity and is very heterogeneous (Table 2 ). It ranges from no neuropsychiatric symptoms among the large group of asymptomatic COVID-19 cases to milder transient neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as fatigue, sleep disturbance and cognitive impairment, predominantly occurring among symptomatic patients with COVID-19 (ref. 55 ). Cognitive impairment consists of sustained memory impairments and executive dysfunction, including short-term memory loss, concentration problems, word-finding problems and impaired daily problem-solving, colloquially termed ‘brain fog’ by patients and clinicians. A small number of infected individuals become severely ill and require hospitalization. During hospital admission, the predominant neuropsychiatric outcome is delirium 56 . Delirium occurs among one-third of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and among over half of patients with COVID-19 who require intensive care unit (ICU) treatment. These delirium rates seem similar to those observed among individuals with severe illness hospitalized for other general medical conditions 57 . Delirium is associated with neuropsychiatric sequalae after hospitalization, as part of post-intensive care syndrome 58 , in which sepsis and inflammation are associated with cognitive dysfunction and an increased risk of a broad range of psychiatric symptoms, from anxiety to depression and psychotic symptoms with hallucinations 59 , 60 .

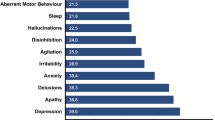

A subset of patients with COVID-19 develop PACS 61 , which can include neuropsychiatric symptoms. A large meta-analysis summarizes 51 studies involving 18,917 patients with a mean follow-up of 77 days (range, 14–182 days) 62 . The most prevalent neuropsychiatric symptom associated with COVID-19 was sleep disturbance, with a pooled prevalence of 27.4%, followed by fatigue (24.4%), cognitive impairment (20.2%), anxiety symptoms (19.1%), post-traumatic stress symptoms (15.7%) and depression symptoms (12.9%) (Table 2 ). Another meta-analysis that assessed patients 12 weeks or more after confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis found that 32% experienced fatigue, and 22% experienced cognitive impairment 63 . To what extent neuropsychiatric symptoms are truly unique for patients with COVID remains unclear from these meta-analyses, as hardly any study included well-matched controls with other types of respiratory infections or inflammatory conditions.

Studies based on electronic health records have examined whether higher levels of neuropsychiatric symptoms truly translate into a higher incidence of clinically overt mental disorders 64 , 65 . In a 1-year follow-up using the US Veterans Affairs database, 153,848 survivors of SARS-CoV-2 infection exhibited an increased incidence of any mental disorder with a relative risk of 1.46 and, specifically, 1.35 for anxiety disorders, 1.39 for depressive disorders and 1.38 for stress and adjustment disorders, compared to a contemporary group and a historical control group ( n = 5,859,251) 65 . In absolute numbers, the incident risk difference attributable to SARS-CoV-2 for mental disorders was 64 per 1,000 individuals. Taquet et al. 64 analyzed electronic health records from the US-based TriNetX network with over 81 million patients and 236,379 COVID-19 survivors followed for 6 months. In absolute numbers, 6-month incidence of hospital contacts related to diagnoses of anxiety, affective disorder or psychotic disorder was 7.0%, 4.5% and 0.4%, respectively. Risks of incident neurological or psychiatric diagnoses were directly correlated with COVID-19 severity and increased by 78% when compared to influenza and by 32% when compared to other respiratory tract infections. In contrast, a medical record study involving 8.3 million adults confirmed that neuropsychiatric disorders were significantly elevated among COVID-19 hospitalized individuals but to a similar extent as in hospitalized patients with other severe respiratory disease 66 . In line with this, a study using language processing of clinical notes in electronic health records did not find an increase in fatigue, mood and anxiety symptoms among COVID-19 hospitalized individuals when compared to hospitalized patients for other indications and adjusted for sociodemographic features and hospital course 67 . It is important to note that research based only on hospital records might be influenced by increased health-seeking behavior that could be differential across care settings or by increased follow-up by hospitals of patients with COVID-19 (compared to patients with other conditions).

Consequently, whether PACS symptoms form a unique pattern due to specific infection with SARS-CoV-2 remains debatable. Prospective case–control studies that do not rely on hospital records but measure the incidence of neuropsychiatric symptoms and diagnoses after COVID-19 are still scarce, but they are critical for distinguishing causation and confounding when characterizing PACS and the uniqueness of neuropsychiatric sequalae after COVID-19 (ref. 68 ). Recent studies with well-matched control groups illustrate that long-term consequences may not be so unique, as they were similar to those observed in patients with other diseases of similar severity, such as after acute myocardial infarction or in ICU patients 56 , 66 . A first prospective follow-up study of COVID-19 survivors and control patients matched on disease severity, age, sex and ICU admission found similar neuropsychiatric outcomes, regarding both new-onset psychiatric diagnosis (19% versus 20%) and neuropsychiatric symptoms (81% versus 93%). However, moderate but significantly worse cognitive outcomes 6 months after symptom onset were found among survivors of COVID-19 (ref. 69 ). In line with this, a longitudinal study of 785 participants from the UK Biobank showed small but significant cognitive impairment among individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 compared to matched controls 70 .

Numerous psychosocial mechanisms can lead to neuropsychiatric sequalae of COVID-19, including functional impairment; psychological impact due to, for example, fear of dying; stress of being infected with a novel pandemic disease; isolation as part of quarantine and lack of social support; fear/guilt of spreading COVID-19 to family or community; and socioeconomic distress by lost wages 71 . However, there is also ample evidence that neurobiological mechanisms play an important role, which is discussed below.

Neurobiological mechanisms underlying neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19

Acute neuropsychiatric symptoms among patients with severe COVID-19 have been found to correlate with the level of serum inflammatory markers 72 and coincide with neuroimaging findings of immune activation, including leukoencephalopathy, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, cytotoxic lesions of the corpus callosum or cranial nerve enhancement 73 . Rare presentations, including meningitis, encephalitis, inflammatory demyelination, cerebral infarction and acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy, have also been reported 74 . Hospitalized patients with frank encephalopathies display impaired blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity with leptomeningeal enhancement on brain magnetic resonance images 75 . Studies of postmortem specimens from patients who succumbed to acute COVID-19 reveal significant neuropathology with signs of hypoxic damage and neuroinflammation. These include evidence of BBB permeability with extravasation of fibrinogen, microglial activation, astrogliosis, leukocyte infiltration and microhemorrhages 76 , 77 . However, it is still unclear to what extent these findings differ from patients with similar illness severity due to acute non-COVID illness, as these brain effects might not be virus-specific effects but rather due to cytokine-mediated neuroinflammation and critical illness.

Post-acute neuroimaging studies in SARS-CoV-2-recovered patients, as compared to control patients without COVID-19, reveal numerous alterations in brain structure on a group level, although effect sizes are generally small. These include minor reduction in gray matter thickness in the various regions of the cortex and within the corpus collosum, diffuse edema, increases in markers of tissue damage in regions functionally connected to the olfactory cortex and reductions in overall brain size 70 , 78 . Neuroimaging studies of post-acute COVID-19 patients also report abnormalities consistent with micro-structural and functional alterations, specifically within the hippocampus 79 , 80 , a brain region critical for memory formation and regulating anxiety, mood and stress responses, but also within gray matter areas involving the olfactory system and cingulate cortex 80 . Overall, these findings are in line with ongoing anosmia, tremors, affect problems and cognitive impairment.

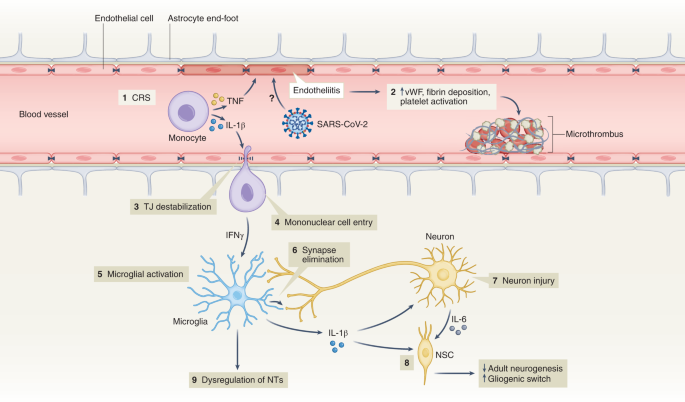

Interestingly, despite findings mentioned above, there is little evidence of SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion with productive replication, and viral material is rarely found in the central nervous system (CNS) of patients with COVID-19 (refs. 76 , 77 , 81 ). Thus, neurobiological mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2-mediated neuropsychiatric sequelae remain unclear, especially in patients who initially present with milder forms of COVID-19. Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with hypoxia, cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and dysregulated innate and adaptive immune responses (reviewed in ref. 82 ). All these effects could contribute to neuroinflammation and endothelial cell activation (Fig. 2 ). Examination of cerebrospinal fluid in patients with neuroimaging findings revealed elevated levels of pro-inflammatory, BBB-destabilizing cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1, IL-8 and mononuclear cell chemoattractants 83 , 84 . Whether these cytokines arise from the periphery, due to COVID-19-mediated CRS, or from within the CNS, is unclear. As studies generally lack control patients with other severe illnesses, the specificity of such findings to SARS-CoV-2 also remains unclear. Systemic inflammatory processes, including cytokine release, have been linked to glial activation with expression of chemoattractants that recruit immune cells, leading to neuroinflammation and injury 85 . Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of neurofilament light, a biomarker of neuronal damage, were reportedly elevated in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 regardless of whether they exhibited neurologic diseases 86 . Acute thromboembolic events leading to ischemic infarcts are also common in patients with COVID-19 due to a potentially increased pro-coagulant process secondary to CRS 87 .

(1) Elevation of BBB-destabilizing cytokines (IL-1β and TNF) within the serum due to CRS or local interactions of mononuclear and endothelial cells. (2) Virus-induced endotheliitis increases susceptibility to microthrombus formation due to platelet activation, elevation of vWF and fibrin deposition. (3) Cytokine, mononuclear and endothelial cell interactions promote disruption of the BBB, which may allow entry of leukocytes expressing IFNg into the CNS (4), leading to microglial activation (5). (6) Activated microglia may eliminate synapses and/or express cytokines that promote neuronal injury. (7) Injured neurons express IL-6 which, together with IL-1β, promote a ‘gliogenic switch’ in NSCs (8), decreasing adult neurogenesis. (9) The combination of microglial (and possibly astrocyte) activation, neuronal injury and synapse loss may lead to dysregulation of NTs and neuronal circuitry. IFNg, interferon-g; NSC, neural stem cell; NT, neurotransmitter; TJ, tight junction; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

It is also unclear whether hospitalized patients with COVID-19 may develop brain abnormalities due to hypoxia or CRS rather than as a direct effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Hypoxia may cause neuronal dysfunction, cerebral edema, increased BBB permeability, cytokine expression and onset of neurodegenerative diseases 88 , 89 . CRS, with life-threatening levels of serum TNF-α and IL-1 (ref. 90 ) could also impact BBB function, as these cytokines destabilize microvasculature endothelial cell junctional proteins critical for BBB integrity 91 . In mild SARS-CoV-2 infection, circulating immune factors combined with mild hypoxia might impact BBB function and lead to neuroinflammation 92 , as observed during infection with other non-neuroinvasive respiratory pathogens 93 . However, multiple studies suggest that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein itself may also induce venous and arterial endothelial cell activation and endotheliitis, disrupt BBB integrity or cross the BBB via adoptive transcytosis 94 , 95 , 96 .

Reducing neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19

The increased risk of COVID-19-related neuropsychiatric sequalae was most pronounced during the first pandemic peak but reduced over the subsequent 2 years 64 , 97 . This may be due to reduced impact of newer SARS-CoV-2 strains (that is, Omicron) but also protective effects of vaccination, which limit SARS-CoV-2 spread and may, thus, prevent neuropsychiatric sequalae. Fully vaccinated individuals with breakthrough infections exhibit a 50% reduction in PACS 98 , even though vaccination does not improve PACS-related neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with a prior history of COVID-19 (ref. 99 ). As patients with pre-existing mental disorders are at increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, they deserve to be among the prioritization groups for vaccination efforts 100 .

Adequate treatment strategies for neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 are needed. As no specific evidence-based intervention yet exists, the best current treatment approach is that for neuropsychiatric sequelae arising after other severe medical conditions 101 . Stepped care—a staged approach of mental health services comprising a hierarchy of interventions, from least to most intensive, matched to the individual’s need—is efficacious with monitoring of mental health and cognitive problems. Milder symptoms likely benefit from counseling and holistic care, including physiotherapy, psychotherapy and rehabilitation. Individuals with moderate to severe symptoms fulfilling psychiatric diagnoses should receive guideline-concordant care for these disorders 61 . Patients with pre-existing mental disorders also deserve special attention when affected by COVID-19, as they have shown to have an increased risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization, complications and death 102 . This may involve interventions to address their general health, any unfavorable socioenvironmental factors, substance abuse or treatment adherence issues.

Lessons learned, knowledge gaps and future challenges

Ultimately, it is not only the millions of people who have died from COVID-19 worldwide that we remember but also the distress experienced during an unpredictable period with overstretched healthcare systems, lockdowns, school closures and changing work environments. In a world that is more and more globalized, connectivity puts us at risk for future pandemics. What can be learned from the last 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic about how to handle future and longstanding challenges related to mental health?

Give mental health equal priority to physical health

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that our population seems quite resilient and adaptive. Nevertheless, even if society as a whole may bounce back, there is a large group of people whose mental health has been and will be disproportionately affected by this and future crises. Although various groups, such as the WHO 8 , the National Health Commission of China 103 , the Asia Pacific Disaster Mental Health Network 104 and a National Taskforce in India 105 , developed mental health policies early on, many countries were late in realizing that a mental health agenda deserves immediate attention in a rapidly evolving pandemic. Implementation of comprehensive and integrated mental health policies was generally inconsistent and suboptimal 106 and often in the shadow of policies directed at containing and reducing the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Leadership is needed to convey the message that mental health is as important as physical health and that we should focus specific attention and early interventions on those at the highest risk. This includes those vulnerable due to factors such as low socioeconomic status, specific developmental life phase (adolescents and young adults), pre-existing risk (poor physical or somatic health and early life trauma) or high exposure to pandemic-related (work) changes—for example, women and healthcare personnel. This means that not only should investment in youth and reducing health inequalities remain at the top of any policy agenda but also that mental health should be explicitly addressed from the start in any future global health crisis situation.

Communication and trust is crucial for mental health

Uncertainty and uncontrollability during the pandemic have challenged rational thinking. Negative news travels fast. Communication that is vague, one-sided and dishonest can negatively impact on mental health and amplify existing distress and anxiety 107 . Media reporting should not overemphasize negative mental health impact—for example, putative suicide rate increases or individual negative experiences—which could make situations worse than they actually are. Instead, communication during crises requires concrete and actionable advice that avoids polarization and strengthens vigilance, to foster resilience and help prevent escalation to severe mental health problems 108 , 109 .

Rapid research should be collaborative and high-quality

Within the scientific community, the topic of mental health during the pandemic led to a multitude of rapid studies that generally had limited methodological quality—for example, cross-sectional designs, small or selective sampling or study designs lacking valid comparison groups. These contributed rather little to our understanding of the mental health impact of the emerging crisis. In future events that have global mental health impact, where possible, collaborative and interdisciplinary efforts with well-powered and well-controlled prospective studies using standardized instruments will be crucial. Only with fine-grained determinants and outcomes can data reliably inform mental health policies and identify who is most at risk.

Do not neglect long-term mental health effects

So far, research has mainly focused on the acute and short-term effects of the pandemic on mental health, usually spanning pandemic effects over several months to 1 year. However, longer follow-up of how a pandemic impacts population mental health is essential. Can societal and economic disruptions after the pandemic increase risk of mental disorders at a later stage when the acute pandemic effects have subsided? Do increased self-reported mental health problems return to pre-pandemic levels, and which groups of individuals remain most affected in the long-term? We need to realize that certain pandemic consequences, particularly those affecting income and school/work careers, may become visible only over the course of several years. Consequently, we should maintain focus and continue to monitor and quantify the effects of the pandemic in the years to come—for example, by monitoring mental healthcare use and suicide. This should include specific at-risk populations (for example, adolescents) and understudied populations in low-income and middle-income countries.

Pay attention to mental health consequences of infectious diseases

Even though our knowledge on PACS is rapidly expanding, there are still many unanswered questions related to who is at risk, the long-term course trajectories and the best ways to intervene early. Consequently, we need to be aware of the neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19 and, for that matter, of any infectious disease. Clinical attention and research should be directed toward alleviating potential neuropsychiatric ramifications of COVID-19. Next to clinical studies, studies using human tissues and appropriate animal models are pivotal to determine the CNS region-specific and neural-cell-specific effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the induced immune activation. Indeed, absence of SARS-CoV-2 neuroinvasion is an opportunity to learn and discover how peripheral neuroimmune mechanisms can contribute to neuropsychiatric sequelae in susceptible individuals. This emphasizes the importance of an interdisciplinary approach where somatic and mental health efforts are combined but also the need to integrate clinical parameters after infection with biological parameters (for example, serum, cerebrospinal fluid and/or neuroimaging) to predict who is at risk for PACS and deliver more targeted treatments.

Prepare mental healthcare infrastructure for pandemic times

If we take mental health seriously, we should not only monitor it but also develop the resources and infrastructure necessary for rapid early intervention, particularly for specific vulnerable groups. For adequate mental healthcare to be ready for pandemic times, primary care, community mental health and public mental health should be prepared. In many countries, health services were not able to meet the population’s mental health needs before the pandemic, which substantially worsened during the pandemic. We should ensure rapid access to mental health services but also address the underlying drivers of poor mental health, such as mitigating risks of unemployment, sexual violence and poverty. Collaboration in early stages across disciplines and expertise is essential. Anticipating disruption to face-to-face services, mental healthcare providers should be more prepared for consultations, therapy and follow-up by telephone, video-conferencing platforms and web applications 51 , 52 . The pandemic has shown that an inadequate infrastructure, pre-existing inequalities and low levels of technological literacy hindered the use and uptake of e-health, both in healthcare providers and in patients across different care settings. The necessary investments can ensure rapid upscaling of mental health services during future pandemics for those individuals with a high mental health need due to societal changes, government measures, fear of infection or infection itself.

Even though much attention has been paid to the physical health consequences of COVID-19, mental health has unjustly received less attention. There is an urgent need to prepare our research and healthcare infrastructures not only for adequate monitoring of the long-term mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic but also for future crises that will shape mental health. This will require collaboration to ensure interdisciplinary and sound research and to provide attention and care at an early stage for those individuals who are most vulnerable—giving mental health equal priority to physical health from the very start.

WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard (WHO, 2022; https://covid19.who.int/

Rando, H. M. et al. Challenges in defining long COVID: striking differences across literature, electronic health records, and patient-reported information. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.20.21253896v1 (2021).

Nalbandian, A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 27 , 601–615 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Abbafati, C. et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396 , 1204–1222 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Penninx, B. W., Pine, D. S., Holmes, E. A. & Reif, A. Anxiety disorders. Lancet 397 , 914–927 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Herrman, H. et al. Time for united action on depression: a Lancet –World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet 399 , 957–1022 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Radka, K., Wyeth, E. H. & Derrett, S. A qualitative study of living through the first New Zealand COVID-19 lockdown: affordances, positive outcomes, and reflections. Prev. Med. Rep. 26 , 101725 (2022).

Mental Health and COVID-19: Early Evidence of the Pandemic’s Impact (WHO, 2022).

Dragioti, E. et al. A large-scale meta-analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID-19 early pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 94 , 1935–1949 (2022).

Zhang, S. X. et al. Mental disorder symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 31 , e23 (2022).

Zhang, S. X. et al. Meta-analytic evidence of depression and anxiety in Eastern Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol . 13 , 2000132 (2022).

Racine, N. et al. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 175 , 1142–1150 (2021).

Robinson, E., Sutin, A. R., Daly, M. & Jones, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J. Affect. Disord. 296 , 567–576 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Prati, G. & Mancini, A. D. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: a review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol. Med. 51 , 201–211 (2021).

Patel, K. et al. Psychological distress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among adults in the United Kingdom based on coordinated analyses of 11 longitudinal studies. JAMA Netw. Open 5 , e227629 (2022).

Ernst, M. et al. Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am. Psychol . 77 , 660–677 (2022).

Kilian, C. et al. Changes in alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Drug Alcohol Rev . 41 , 918–931 (2022).

Acuff, S. F., Strickland, J. C., Tucker, J. A. & Murphy, J. G. Changes in alcohol use during COVID-19 and associations with contextual and individual difference variables: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 36 , 1–19 (2022).

Varga, T. V. et al. Loneliness, worries, anxiety, and precautionary behaviours in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of 200,000 Western and Northern Europeans. Lancet Reg. Health Eur . 2 , 100020 (2021).

Fancourt, D., Steptoe, A. & Bu, F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 141–149 (2021).

Jia, H. et al. National and state trends in anxiety and depression severity scores among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 70 , 1427–1432 (2021).

Kok, A. A. L. et al. Mental health and perceived impact during the first Covid-19 pandemic year: a longitudinal study in Dutch case–control cohorts of persons with and without depressive, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 305 , 85–93 (2022).

Su, Y. et al. Prevalence of loneliness and social isolation among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610222000199 (2022).

Knox, L., Karantzas, G. C., Romano, D., Feeney, J. A. & Simpson, J. A. One year on: what we have learned about the psychological effects of COVID-19 social restrictions: a meta-analysis. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 46 , 101315 (2022).

Aknin, L. B. et al. Policy stringency and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of data from 15 countries. Lancet Public Health 7 , e417–e426 (2022).

Lee, Y. et al. Government response moderates the mental health impact of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of depression outcomes across countries. J. Affect. Disord. 290 , 364–377 (2021).

Wu, J. T. et al. Nowcasting epidemics of novel pathogens: lessons from COVID-19. Nat. Med. 27 , 388–395 (2021).

Brooks, S. K. et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395 , 912–920 (2020).

Santomauro, D. F. et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398 , 1700–1712 (2021).

Knudsen, A. K. S. et al. Prevalence of mental disorders, suicidal ideation and suicides in the general population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway: a population-based repeated cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Reg. Health Eur . 4 , 100071 (2021).

Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. et al. Changes in depression and suicidal ideation under severe lockdown restrictions during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: a longitudinal study in the general population. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci . 30 , e49 (2021).

Vloo, A. et al. Gender differences in the mental health impact of the COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal evidence from the Netherlands. SSM Popul. Health 15 , 100878 (2021).

Winkler, P. et al. Prevalence of current mental disorders before and during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of repeated nationwide cross-sectional surveys. J. Psychiatr. Res. 139 , 167–171 (2021).

Pirkis, J. et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 579–588 (2021).

Faust, J. S. et al. Mortality from drug overdoses, homicides, unintentional injuries, motor vehicle crashes, and suicides during the pandemic, March–August 2020. JAMA 326 , 84–86 (2021).

John, A. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: update of living systematic review. F1000Res. 9 , 1097 (2020).

Steeg, S. et al. Temporal trends in primary care-recorded self-harm during and beyond the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: time series analysis of electronic healthcare records for 2.8 million patients in the Greater Manchester Care Record. EClinicalMedicine 41 , 101175 (2021).

Rømer, T. B. et al. Psychiatric admissions, referrals, and suicidal behavior before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark: a time-trend study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 144 , 553–562 (2021).

Holland, K. M. et al. Trends in US emergency department visits for mental health, overdose, and violence outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry 78 , 372–379 (2021).

Kunzler, A. M. et al. Mental burden and its risk and protective factors during the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: systematic review and meta-analyses. Global Health 17 , 34 (2021).

Flor, L. S. et al. Quantifying the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality on health, social, and economic indicators: a comprehensive review of data from March, 2020, to September, 2021. Lancet 399 , 2381–2397 (2022).

Viner, R. et al. School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 176 , 400–409 (2022).

Zheng, X. Y. et al. Trends of injury mortality during the COVID-19 period in Guangdong, China: a population-based retrospective analysis. BMJ Open 11 , e045317 (2021).

Tanaka, T. & Okamoto, S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 229–238 (2021).

Thomeer, M. B., Moody, M. D. & Yahirun, J. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01006-7 (2022).

Hill, J. E. et al. The prevalence of mental health conditions in healthcare workers during and after a pandemic: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 78 , 1551–1573 (2022).

Marvaldi, M., Mallet, J., Dubertret, C., Moro, M. R. & Guessoum, S. B. Anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 126 , 252–264 (2021).

Phiri, P. et al. An evaluation of the mental health impact of SARS-CoV-2 on patients, general public and healthcare professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 34 , 100806 (2021).

Jorm, A. F., Patten, S. B., Brugha, T. S. & Mojtabai, R. Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders? Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry 16 , 90–99 (2017).

Third Round of the Global Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic (WHO, 2021).

Baumgart, J. G. et al. The early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health facilities and psychiatric professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 , 8034 (2021).

Raphael, J., Winter, R. & Berry, K. Adapting practice in mental healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic and other contagions: systematic review. BJPsych Open 7 , e62 (2021).

Anderson, K. N. et al. Changes and inequities in adult mental health-related emergency department visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Psychiatry 79 , 475–485 (2022).

Pan, K. Y. et al. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: a longitudinal study of three Dutch case–control cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 121–129 (2021).

Dantzer, R., O’Connor, J. C., Freund, G. G., Johnson, R. W. & Kelley, K. W. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 , 46–56 (2008).

Nersesjan, V. et al. Central and peripheral nervous system complications of COVID-19: a prospective tertiary center cohort with 3-month follow-up. J. Neurol. 268 , 3086–3104 (2021).

Wilson, J. E. et al. Delirium. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim . 6 , 90 (2020).

Rawal, G., Yadav, S. & Kumar, R. Post-intensive care syndrome: an overview. J. Transl. Intern. Med. 5 , 90–92 (2017).

Pandharipande, P. P. et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N. Engl. J. Med. 369 , 1306–1316 (2013).

Girard, T. D. et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective cohort study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 33 , 929–935 (2018).

Crook, H., Raza, S., Nowell, J., Young, M. & Edison, P. Long covid—mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ 374 , n1648 (2021).

Badenoch, J. B. et al. Persistent neuropsychiatric symptoms after COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Commun . 4 , fcab297 (2021).

Ceban, F. et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 101 , 93–135 (2022).

Taquet, M., Geddes, J. R., Husain, M., Luciano, S. & Harrison, P. J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 416–427 (2021).

Xie, Y., Xu, E. & Al-Aly, Z. Risks of mental health outcomes in people with covid-19: cohort study. BMJ 376 , e068993 (2022).

Kieran Clift, A. et al. Neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 and other severe acute respiratory infections. JAMA Psychiatry 79 , 690–698 (2022).

Castro, V. M., Rosand, J., Giacino, J. T., McCoy, T. H. & Perlis, R. H. Case–control study of neuropsychiatric symptoms following COVID-19 hospitalization in 2 academic health systems. Mol. Psych. (in the press).

Amin-Chowdhury, Z. & Ladhani, S. N. Causation or confounding: why controls are critical for characterizing long COVID. Nat. Med. 27 , 1129–1130 (2021).

Nersesjan, V. et al. Neuropsychiatric and cognitive outcomes in patients 6 months after COVID-19 requiring hospitalization compared with matched control patients hospitalized for non-COVID-19 illness. JAMA Psychiatry 79 , 486–497 (2022).

Douaud, G. et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature 604 , 697–707 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Psychological experience of COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Am. J. Infect. Control 50 , 809–819 (2022).

Mazza, M. G. et al. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav. Immun. 89 , 594–600 (2020).

Moonis, G. et al. The spectrum of neuroimaging findings on CT and MRI in adults With COVID-19. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 217 , 959–974 (2021).

Asadi-Pooya, A. A. & Simani, L. Central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. J. Neurol. Sci . 413 , 116832 (2020).

Lersy, F. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid features in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 and neurological manifestations: correlation with brain magnetic resonance imaging findings in 58 patients. J. Infect. Dis. 223 , 600–609 (2021).

Thakur, K. T. et al. COVID-19 neuropathology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/New York Presbyterian Hospital. Brain 144 , 2696–2708 (2021).

Cosentino, G. et al. Neuropathological findings from COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms argue against a direct brain invasion of SARS-CoV-2: a critical systematic review. Eur. J. Neurol. 28 , 3856–3865 (2021).

Tian, T. et al. Long-term follow-up of dynamic brain changes in patients recovered from COVID-19 without neurological manifestations. JCI Insight 7 , e155827 (2022).

Lu, Y. et al. Cerebral micro-structural changes in COVID-19 patients—an MRI-based 3-month follow-up study. EClinicalMedicine 25 , 100484 (2020).

Qin, Y. et al . Long-term microstructure and cerebral blood flow changes in patients recovered from COVID-19 without neurological manifestations. J. Clin. Invest . 131 , e147329 (2021).

Matschke, J. et al. Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: a post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 19 , 919–929 (2020).

Shivshankar, P. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection: host response, immunity, and therapeutic targets. Inflammation 45 , 1430–1449 (2022).

Manganotti, P. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum interleukins 6 and 8 during the acute and recovery phase in COVID-19 neuropathy patients. J. Med. Virol. 93 , 5432–5437 (2021).

Farhadian, S. et al. Acute encephalopathy with elevated CSF inflammatory markers as the initial presentation of COVID-19. BMC Neurol . 20 , 248 (2020).

Francistiová, L. et al. Cellular and molecular effects of SARS-CoV-2 linking lung infection to the brain. Front. Immunol . 12 , 730088 (2021).

Paterson, R. W. et al. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid biomarker profiles in acute SARS-CoV-2-associated neurological syndromes. Brain Commun . 3 , fcab099 (2021).

Cryer, M. J. et al. Prothrombotic milieu, thrombotic events and prophylactic anticoagulation in hospitalized COVID-19 positive patients: a review. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost . 28 , 10760296221074353 (2022).

Nalivaeva, N. N. & Rybnikova, E. A. Editorial: Brain hypoxia and ischemia: new insights into neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. Front. Neurosci . 13 , 770 (2019).

Brownlee, N. N. M., Wilson, F. C., Curran, D. B., Lyttle, N. & McCann, J. P. Neurocognitive outcomes in adults following cerebral hypoxia: a systematic literature review. NeuroRehabilitation 47 , 83–97 (2020).

Del Valle, D. M. et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat. Med. 26 , 1636–1643 (2020).

Daniels, B. P. et al. Viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns regulate blood–brain barrier integrity via competing innate cytokine signals. mBio 5 , e01476-14 (2014).

Reynolds, J. L. & Mahajan, S. D. SARS-COV2 alters blood brain barrier integrity contributing to neuro-inflammation. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 16 , 4–6 (2021).

Bohmwald, K., Gálvez, N. M. S., Ríos, M. & Kalergis, A. M. Neurologic alterations due to respiratory virus infections. Front. Cell. Neurosci . 12 , 386 (2018).

Khaddaj-Mallat, R. et al. SARS-CoV-2 deregulates the vascular and immune functions of brain pericytes via spike protein. Neurobiol. Dis . 161 , 105561 (2021).

Qian, Y. et al. Direct activation of endothelial cells by SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein is blocked by simvastatin. J Virol. 95 , e0139621 (2021).

Rhea, E. M. et al. The S1 protein of SARS-CoV-2 crosses the blood–brain barrier in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 24 , 368–378 (2021).

Magnúsdóttir, I. et al. Acute COVID-19 severity and mental health morbidity trajectories in patient populations of six nations: an observational study. Lancet Public Health 7 , e406–e416 (2022).

Antonelli, M. et al. Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: a prospective, community-based, nested, case–control study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22 , 43–55 (2022).

Wisnivesky, J. P. et al. Association of vaccination with the persistence of post-COVID symptoms. J. Gen. Intern. Med . 37 , 1748–1753 (2022).

De Picker, L. J. et al. Severe mental illness and European COVID-19 vaccination strategies. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 356–359 (2021).

Cohen, G. H. et al. Comparison of simulated treatment and cost-effectiveness of a stepped care case-finding intervention vs usual care for posttraumatic stress disorder after a natural disaster. JAMA Psychiatry 74 , 1251–1258 (2017).

Vai, B. et al. Mental disorders and risk of COVID-19-related mortality, hospitalisation, and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 797–812 (2021).

Xiang, Y. T. et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 7 , 228 (2020).

Newnham, E. A. et al. The Asia Pacific Disaster Mental Health Network: setting a mental health agenda for the region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 , 6144 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dandona, R. & Sagar, R. COVID-19 offers an opportunity to reform mental health in India. Lancet Psychiatry 8 , 9–11 (2021).

Qiu, D. et al. Policies to improve the mental health of people influenced by COVID-19 in China: a scoping review. Front. Psychiatry 11 , 588137 (2020).

Su, Z. et al. Mental health consequences of COVID-19 media coverage: the need for effective crisis communication practices. Global Health 17 , 4 (2021).

Petersen, M. B. COVID lesson: trust the public with hard truths. Nature 598 , 237 (2021).

van der Bles, A. M., van der Linden, S., Freeman, A. L. J. & Spiegelhalter, D. J. The effects of communicating uncertainty on public trust in facts and numbers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 7672–7683 (2020).

Titze-de-Almeida, R. et al. Persistent, new-onset symptoms and mental health complaints in Long COVID in a Brazilian cohort of non-hospitalized patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 22 , 133 (2022).

Carfì, A., Bernabei, R. & Landi, F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA 324 , 603–605 (2020).

Bliddal, S. et al. Acute and persistent symptoms in non-hospitalized PCR-confirmed COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 11 , 13153 (2021).

Kim, Y. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome in patients after 12 months from COVID-19 infection in Korea. BMC Infect. Dis . 22 , 93 (2022).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank E. Giltay for assistance on data analyses and production of Fig. 1 . B.W.J.H.P. discloses support for research and publication of this work from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme-funded RESPOND project (grant no. 101016127).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry, Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Brenda W. J. H. Penninx & Christiaan H. Vinkers

Amsterdam Public Health, Mental Health Program and Amsterdam Neuroscience, Mood, Anxiety, Psychosis, Sleep & Stress Program, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Biological and Precision Psychiatry, Copenhagen Research Center for Mental Health, Mental Health Center Copenhagen, Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark

Michael E. Benros

Department of Immunology and Microbiology, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Departments of Medicine, Pathology & Immunology and Neuroscience, Center for Neuroimmunology & Neuroinfectious Diseases, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA

Robyn S. Klein

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Brenda W. J. H. Penninx .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Medicine thanks Jane Pirkis and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editor: Karen O’Leary, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Penninx, B.W.J.H., Benros, M.E., Klein, R.S. et al. How COVID-19 shaped mental health: from infection to pandemic effects. Nat Med 28 , 2027–2037 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02028-2

Download citation

Received : 06 June 2022

Accepted : 26 August 2022

Published : 03 October 2022

Issue Date : October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02028-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

IMAGES