- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Learning Through Discussion

Discussions can be meaningful and engaging learning experiences: dynamic, eye-opening, and generative. However, like any class activity, they require planning and preparation. Without that, discussion challenges can arise in the form of unequal participation, unclear learning outcomes, or low engagement. This resource presents key considerations in class discussions and offers strategies for how instructors can prepare and engage in effective classroom discussions.

On this page:

- The What and Why of Class Discussion

Identifying your Course Context

- Plan for Classroom Discussion

- Warm up Classroom Discussion

- Engage in Classroom Discussion

- Wrap up Classroom Discussion

Leveraging Asynchronous Discussion Spaces

- References and Further Reading

The CTL is here to help!

Seeking additional support with discussion pedagogy? Email [email protected] to schedule a 1-1 consultation. For support with any of the Columbia tools discussed below, email [email protected] or join our virtual office hours .

Interested in inviting the CTL to facilitate a session on this topic for your school, department, or program? Visit our Workshops To Go page for more information.

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Learning Through. DIscussion. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/learning-through-discussion/

The What and Why of Class Discussion

Class discussion can take many forms, from structured prompts and assignments to more casual or informal conversations. Regardless of class context (e.g.: a seminar, large lecture, or lab course) or the form (e.g.: in-person or asynchronous) discussion takes, it offers a number of benefits to students’ learning. As an active learning technique, class discussion requires students to be co-constructors of their learning. Research shows that students learn more when they actively participate in their learning, rather than passively listen. Furthermore, studies have also shown that “student participation, encouragement, and peer-to-peer interaction was consistently and positively related to the development of critical thinking skills” (Howard, 2015, pp. 6). Class discussion has also been linked to greater student motivation, improved communication skills, and higher grades (Howard, 2015). But just like effective lectures or assignments require planning and preparation, so too does class discussion.

The following sections offer a framework and strategies for learning through discussion. These strategies are organized around four key phases: planning for classroom discussion, warming up for classroom discussion, engaging in classroom discussion, and wrapping up classroom discussion.

While the strategies and considerations provided throughout this resource are adaptable across course contexts, it is important to recognize instructors’ varied course formats, and how discussion might differ across them. This section identifies a few of these contexts, and reviews how these contexts might shape instructors’ engagement with both this resource and class discussion more broadly.

I teach a discussion-based course

Small classes and seminars use discussion-based pedagogies, though it can be challenging to get every student to contribute to discussions. It is important to create multiple opportunities for engagement and not just rely on whole group discussion. Pair and small group discussions can create trust among students and give them the confidence to speak up in the larger group. Instructors of discussion-based courses can extend in-class discussions into the asynchronous space. These inclusive moves allow students to contribute to discussions in multiple ways.

I do not teach a discussion-based course

Whether teaching a large lecture course, a lab course, or other non-discussion based course, students will still benefit from interacting with each other and learning through discussion. Small group or pair discussion can be less intimidating for students regardless of class size and help create a sense of community that impacts learning.

I teach a course that may have some Hybrid/HyFlex meetings.

In-person classes might sometimes offer hybrid or HyFlex opportunities for students to accommodate extenuating circumstances. In a hybrid/HyFlex course session, students participating in-person and remotely should have equal opportunities to contribute to discussions. To make this a reality, advanced preparation involves thinking through the logistics using discussion activities, roles and responsibilities (if working with TA(s)), classroom technologies (e.g., ceiling microphones available in the classroom; asking in-person students to bring a mobile device and headset if possible to engage with their remote peers), and determining the configurations if using discussion groups or paired work (both in a socially distanced classroom, and if asking both in-person and remote students to discuss together in breakout groups).

Planning for Classroom Discussion

Regardless of your course context, there are some general considerations for planning a class discussion; these considerations include: the goals and expectations, the modality of discussion, and the questions you might use to prompt discussion. The following section offers some questions for reflection, alongside ideas and strategies to address these considerations.

Goals & Expectations

What is the goal of the discussion? How will it support student learning? What are your expectations of student participation and contributions to the discussion? How will you communicate the goals and expectations to students?

Articulate the goals of discussion : Consider both the content you want your students to learn and the skills you want them to apply and develop. These goals will inform the learner-centered strategies and digital tools you use during discussion.

Communicate the purpose (not just the topic) of discussion: Sharing learning goals will help students understand why discussion is being used and how it will contribute to their learning.

Specify what you expect of student contributions to the discussion and how they will be assessed: Be explicit about what students should include in their contributions to make them substantive, and model possible ways of responding. Guide students in how they can contribute substantively to their peers’ live responses or online posts. You might consider asking students to use the 3CQ model:

- Compliment—I like that ___ because…;

- Comment—I agree/disagree with (specific point/idea) because…;

- Connection—I also thought that…;

- Question—I wonder why…

Establish discussion guidelines: Communicate expectations for class discussion. Be sure to include desired behaviors/etiquette and how technologies and tools for discussion will be used. Students in all classes can benefit from discussion guidelines as they help to clearly identify and establish expectations for student success. For more support with getting started, see the Barnard Center for Engaged Pedagogy’s resource on Crafting Community Agreements . Additionally, while there are some shared general discussion guidelines, there are also some specific considerations for asynchronous discussions:

In this short video, learn more about creating community agreements in the classroom, as part of the CTL’s “Teaching Talks” initiative.

Sample Discussion Guidelines:

- Refer to classmates by name.

- Allow everyone the chance to speak (“Take Space, Make Space”).

- Constructively critique ideas, not individuals.

- Listen actively without interrupting.

- Contribute questions, ideas, or resources.

Sample Asynchronous Discussion Guidelines:

- Respond to discussion posts within # of hours or days.

- Review one’s own writing for clarity before posting, being mindful of how it may be interpreted by others.

- Prioritize building upon or challenging the strongest ideas presented in a post instead of only focusing on the weakest aspects.

- Acknowledge something someone else said.

- Build on their comment by connecting with course content, adding an example or observation.

- Conclude with critical thinking or socratic questions.

Invite students to revise, contribute to, or co-create the guidelines. One way to do this is to facilitate a discussion about discussions, asking students to identify what the characteristics of an effective discussion are. This will encourage their ownership of the guidelines. Post the guidelines in CourseWorks and refer to them as needed.

In what modality/modalities will the discussion take place (in-person/live, asynchronous, or a blend of both)?

The modality of your class discussion may determine the tools and technologies that you ask students to engage with. Thus, it is important to determine early on how you would like students to engage in discussion and what tools you will use to support their engagement. Consider leveraging your asynchronous course spaces (e.g., CourseWorks), which can help students both prepare for an in-class discussion, as well expand upon and continue in-class discussions. For support with setting up asynchronous discussions, see the Leveraging Asynchronous Discussion Spaces section below.

What prompts will be used for discussion? Who will come up with those prompts (e.g.: instructor, TA, or students)?

The questions you ask and how you ask them are important for leading an effective discussion. Discussion questions do not have to be instructor-generated; asking students to generate discussion prompts is a great way to engage them in their learning.

Draft open-ended questions that advance student learning and inspire a range of answers (avoiding closed-ended, vague, or leading questions). Vary question complexity over the course of a discussion. If there’s one right answer, ask students about their process to get to the right answer.

The following table features sample questions that increase in cognitive complexity and is based on the six categories of the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Warming up for Classroom Discussion

Get students comfortable talking with their peers, you, and the TA(s) (as applicable) from the start of the course. Create opportunities for students to have pair or small group conversations to get to know one another and connect as a community. Regardless of your class size or context (i.e.: seminars, large-lecture classes, labs), for discussions to become a norm in your course, you will need to build community early on in the course.

Get students talking early and often to foster community

How will you make peer-to-peer engagement an integral part of your class? How can you get students talking to each other?

To encourage student participation and peer-to-peer interaction, create early and frequent opportunities for students to share and talk with each other. These opportunities can help make students more comfortable with participating in discussion, as well as help build rapport and foster trust amongst class members. Icebreakers and small group discussion opportunities provide great ways to get students talking, especially in large-enrollment classes where students may feel less connection with their peers (see sample icebreakers below ). For additional support with building community in your course, see the CTL’s Community Building in Online and Hybrid (HyFlex) Courses resource. (Although this resource emphasizes online and hybrid/HyFlex modalities, the strategies provided are applicable across all course modalities.)

Establish class norms around discussion and participation

How can you communicate class norms around discussion and participation on day one?

The first class meeting is an opportunity to warm students up to class discussion and participation from the outset. Rather than letting norms of passivity establish over the first couple of weeks, you can use the first class meeting to signal to students they will be expected to participate or interact with their peers regularly. You might ask students to do a welcoming icebreaker on the first day, or you might invite questions and syllabus discussion. No matter the activity, establishing a norm around discussion and participation at the outset will help warm students up to participating and contributing to later discussions; these norms can also be further supported by your discussion guidelines . Icebreakers: Icebreakers are a great way to establish a positive course climate and encourage student-student, as well as instructor-student, interactions. Some ideas for icebreaker activities related to discussion include:

- (Meta)Discussion about Discussions: In small groups during class, or using a CourseWorks discussion board , students introduce themselves to each other, and share their thoughts on what are the qualities of good and bad discussions.

- Course Content: Ask students to share their thoughts about a big question that the course addresses or ask students what comes to mind when they think of an important course concept. You could even ask students to scan the syllabus and share about a particular topic or reading they are most excited about.

Engaging in Classroom Discussion

With all of your preparation and planning complete, there are some important considerations you will need to make with both your students and yourself in mind. This section offers some strategies for engaging in classroom discussion.

Involve students in discussion

How will you engage all of your students in the discussion? How will you make discussion and your expectations about student participation explicit and integral to the class?

Involving your students in class discussion will allow for more student voices and perspectives to be contributed to the conversation. You might consider leveraging the time before and after class or office hours to have informal conversations and build rapport with students. Additionally, having students rotate roles and responsibilities can keep them focused and engaged.

Student roles: Engage all students by asking them to volunteer for and rotate through roles such as facilitator, summarizer, challenger, etc. In large-enrollment courses, these roles can be assigned in small group or pair discussions. For an asynchronous discussion, roles might include: discussion starter / original poster, connector to research, connector to theory. Additional roles might include: timekeeper, notetaker, discussion starter, wrapper, and student monitor:

- Discussion starter / original poster: Involve students in initiating the discussion. Designate 2–3 students per discussion to spark the conversation with a question, quotation, an example, or link to previous course content.

- Discussion wrapper: Engage students in facilitating the discussion. Help students grasp take-aways. Designate 2-3 students per discussion to wrap up the discussion by identifying themes, extracting key ideas, or listing questions to explore further.

- Student monitor: Ask a student (on a rotating basis) or TA(s) if applicable, to monitor the Zoom chat (in hybrid/HyFlex courses) or the CourseWorks Discussion Boards (when leveraging asynchronous discussion spaces). The monitors can then flag important points for the class or read off the questions that are being posed.

Student-generated questions: Prepare students for discussion and involve them in asking and answering peer questions about the topic. Invite students to post questions to a CourseWorks Discussion before class, or share their questions during the discussion. If students are expected to respond to their peer’s questions, they need to be told and guided how to do so. Highlight and use insightful student questions to prime or further the discussion.

Student-led presentations: In smaller seminar-style classes or labs, invite students to give informal presentations. You might ask them to share examples that relate to the topic or concept being discussed, or respond to a targeted prompt.

Determine your role in discussion

How will you facilitate discussion? What will your presence be in asynchronous discussion spaces? What can students expect of your role in the discussion?

Make your role (or that of your co-instructor(s) and/or TA(s)) in the discussion explicit so that students know what to expect of your presence, reinforcement of the discussion guidelines, and receipt of feedback.

Actively guide the discussion to make it easy for students to do most of the talking and/or posting. This includes being present, modeling contributions, asking questions, using students’ names, giving timely feedback, affirming student contributions, and making inclusive moves such as including as many voices and perspectives and addressing issues that may arise during a conversation.

- For in-class discussions , additional strategies include actively listening, giving students time to think before responding, repeating questions, and warm calling. (Unlike cold calling, warm calling is when students do pre-work and are told in advance that they will be asked to share their or their group’s response. This technique can minimize student anxiety, as well as produce higher quality responses.)

- For asynchronous discussions , additional strategies include having parallel discussions in small groups on CourseWorks, and inviting students to post videos, audio clips, or images such as drawings, maps, charts, etc.

Manage the discussion and intervene when necessary : Manage dynamics, recognizing that your classroom is influenced by societal norms and expectations that may be inherently inequitable. Moderate the ongoing discussion to make sure all students have the opportunity to contribute. Ask students to explain or provide evidence to support their contributions, connect their contributions to specific course concepts and readings, redirect or keep the conversation on track, and revisit discussion guidelines as needed.

For large-enrollment courses, you might ask TAs or course assistants to join small groups or monitor discussion board posting. While it’s important for students to do most of the talking and posting, TAs can support students in the discussion, and their presence can help keep the discussion on track. If you have TAs who lead discussion sections, you might consider sharing some of these discussion management strategies and considerations with them, and discuss how the discussion sections can and will expand upon discussions from the larger class.

Give students time to think before, during, and after the discussion

Thinking time will allow students to prepare more meaningful contributions to the discussion and creates opportunities for more students, not just the ones that are the quickest to respond, to contribute to the conversation. Comfort with silence is important following a posed question. Some thinking time activities include:

- “ Silent meeting ” (Armstrong, 2020): Devote class time to students silently engaging with course materials and commenting in a shared document. You can follow this “silent meeting” with small group discussions. In a large enrollment class, this strategy can allow students to engage more deeply and collaboratively with material and their peers.

- Think-Pair-Share : Give students time to think before participating. In response to an open-ended question, ask students to first think on their own for a few minutes, then pair up to discuss their ideas with their partner. Finally, ask a few pairs to share their main takeaways with the whole class.

- Discussion pause : Give students time to think and reflect on the discussion so far. Pause the discussion for a few minutes for students to independently restate the question, issue, or problem, and summarize the points made. Encourage students to write down new insights, unanswered questions, etc.

- Extend the discussion: Encourage students to continue the class discussion by leveraging asynchronous course spaces (e.g.: CourseWorks discussion board). You may ask students to summarize the discussion, extend the discussion by contributing new ideas, or pose follow-up questions that will be discussed asynchronously or used to begin the next in-class discussion.

- Polls to launch the discussion : Pose a poll closed-ended question and give students time to think and respond individually. See responses in real time and ask students to discuss the results. This can be a great warm up activity for a pair, small group, or whole class discussion, especially in large classes in which it may be more challenging to engage all students.

Wrapping up Classroom Discussion

Ensure that the discussion meets the learning objectives of the course or class session, and that students are leaving the discussion with the knowledge and skills that you want them to acquire. Give students an opportunity to reflect on and share what they have learned. This will help them make connections between other class material and previous class discussions. It is also an opportunity for you to gauge how the discussion went and consider what you might need to clarify or shift for future discussions.

Debrief the Discussion

How will you know the discussion has met the learning objectives of the course or class session? How will you ensure students make connections between broader course concepts and the discussion?

Set aside time to debrief the discussion. This might be groups sharing out their discussion take-aways, designated students summarizing the key points made and questions raised, or asking students to reflect and share what they learned. Rather than summarizing the discussion yourself, partner with your students; see the section on Student Roles above for strategies.

- Closing Reflection: Ask students to reflect on and process their learning by identifying key takeaways. Carve out 2-5 minutes at the end of class for students to reflect on the discussion, either in writing or orally. You might consider collecting written reflections from students at the end of class, or after class through a Google Form or CourseWorks post. Consider asking students to not only reflect on what they learned from the discussion, but to also summarize key ideas or insights and/or pose new questions.

Collect Feedback, Reflect, Iterate

How will you determine the effectiveness of class discussion? How can you invite students into creating the learning space?

Feedback: Student feedback is a great way to gauge the effectiveness and success of class discussion. It’s important to include opportunities for feedback regularly and frequently throughout the semester; for feedback collection prompts and strategies, see the CTL’s resource on Early and Mid-Semester Student Feedback . You might collect this through PollEverywhere, a Google Form, or CourseWorks Survey. Classes of all sizes and modalities can benefit from collecting this type of feedback from students.

Reflect: Before you engage with your students’ feedback, it’s important to take time and reflect for yourself: How do you think the discussion went? Did your students achieve the learning goals that you had hoped? If not, what might you do differently? You can then couple your own reflection with your students’ feedback to determine what is working well, as well as what might need to change for discussions to be more effective.

Iterate: Not all class discussions will go according to plan, but feedback and reflection can help you identify those key areas for improvement. Share aggregate feedback data with your students, as well as what you hope will go differently in future discussions.

Asynchronous discussion spaces are an effective way for students to prepare for in-class discussion, as well as expand upon what they have already discussed in class. Asynchronous discussion boards also offer a great space for students to reflect upon the discussion, and provide informal feedback.

Columbia Tools to Support Asynchronous Discussion

There are a number of Columbia tools that can support asynchronous discussion spaces. Some options that instructors might consider include:

- CourseWorks Discussion boards : CourseWorks discussion boards offer instructors a number of customizable options including: threaded or focused discussions , post “like” functionality , graded discussion posts , group discussions , and more. For further support with your CourseWorks discussion board, see the CTL’s CourseWorks Support Page or contact the CTL at [email protected] to set up a consultation.

- Ed Discussion (via CourseWorks): Starting in Fall 2021, instructors will have access to Ed Discussion within their CourseWorks site. For support on getting started with Ed Discussion, see their Quick Start Guide , or contact the CTL at [email protected] . For strategies and examples on how to enhance your course’s asynchronous discussion opportunities using Ed Discussion’s advanced features, refer to Enhance your Course Discussion Boards for Learning: Three Strategies Using Ed Discussion .

References and Further Reading

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Armstrong, B. (2020). To Spark Discussion in a Zoom Class, Try a ‘Silent Meeting .’ The Chronicle of Higher Education. November 18, 2020.

Barkley, E.F. (2010). Student Engagement Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty . Jossey-Bass.

Barkley, E.F.; Major, C.H.; and Cross, K.P. (2014). Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty . Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Barnard Center for Engaged Pedagogy. (2021). Crafting community agreements .

Brookfield, S. D., & Preskill, S. (2016). The Discussion Book: 50 Great Ways to Get People Talking . Wiley.

Cashin, W.E. (2011). Effective Classroom Discussions . IDEA Paper #49. Retrieved from www.ideaedu.org

Center for Research on Teaching and Learning. Guidelines For Classroom Interactions. Retrieved from http://www.crlt.umich.edu/examples-discussion-guidelines

Davis, B.G. (2009). Tools for Teaching , 2 nd Edition.

Hancock, C., & Rowland, B. (2017). Online and out of synch: Using discussion roles in online asynchronous discussions. Cogent Education, 4(1).

Howard, J.R. (2015). Discussion in the College Classroom: Getting Your Students Engaged and Participating in Person and Online . Wiley.

Howard, J.R. (2019) How to Hold a Better Class Discussion: Advice Guide. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/interactives/20190523-ClassDiscussion

The K. Patricia Cross Academy. Making Good Use of Online Discussion Boards. Retrieved from https://kpcrossacademy.org/making-good-use-of-online-discussion-boards/

Read more about Columbia undergraduate students’ experiences with discussion

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Trending Post : 12 Powerful Discussion Strategies to Engage Students

12 Powerful Discussion Strategies to Engage Students

Inside: Looking for collaborative class discussion strategies that work across settings? This post is full of a variety of engaging technology and formatting options for blended learning, online teaching, and face-to-face instruction.

Whether you have students at home, in school, or BOTH at the same time, you’re probably looking for ways to engage tweens and teens in meaningful conversations. Discussion strategies are changing. With the demands of social distancing and multiple settings, teachers are getting creative, looking for ways to bring students together, even when we are apart.

I wanted to compile a fresh list of inspiration for online discussions, so I reached out to some of my middle and high school teacher friends around the web. The result? This post is FULL of classroom-tested discussion strategies for collaborative conversations. You’ll find a variety of tech tools that bridge the gap between home and school as well as formatting ideas for how to run whole-class and small-group discussions.

CLASS DISCUSSION STRATEGIES: TECH IDEAS

When it comes to technology, sometimes less is more. BUT! If students and teachers know how to use technology to make discussions efficient and effective, they can be just what you need to host meaningful class conversations across settings. These discussion strategies utilize tech tools that enhance learning and connectedness.

1. Silent Discussions

Silent discussion strategies have been gaining momentum in the physical classroom, but they are also convenient for online discussions.

Consider… students with devices where the microphones may or may not work? Noisy distractions in the home environment? Students tuning in live from home with other students sitting in the classroom?

Silent discussions can bridge the gap.

How it works:

In order to make a virtual or blended learning silent discussion work, we first have to select the technology we need. In person, teachers often use big paper or graffiti walls. So, I started brainstorming how those engaging techniques can transfer to online learning.

A few options…

With Mentimeter , teachers can create a variety of poll questions to engage students in a variety of settings. You can create your interactive questions in different formats: word clouds, rankings, spider webs, bar charts, quadrants, word walls, and more. Teachers can create three-slide presentations for free. Students have easy access on any device by navigating to menti.com and then typing in the code at the top of the page.

Padlet is another tech platform teachers can use to hold silent discussions. Students can synchronously or asynchronously post original ideas in response to discussion questions in grid, timeline, map, wall, column, and other arrangements. One of the best parts is that students can post links to related articles or videos and original photographs they’ve taken. Plus, they can build on their peer’s posts to create an ongoing conversation.

Finally, Backchannel chat is a convenient, free chat-style tool. While students are having a discussion either in person or online, non-verbal participants can be talking via the backchannel chat. I recommend – if possible – having two screens so that you can view students’ faces on one (if you have students at home) and the backchannel chat on another.

Why it works:

Each of these silent discussion tech tools provides an avenue for students at home to be engaging with students at school. And, when all students are in the classroom together, they provide intentional avenues to give each student ownership and a voice in the discussion.

2. Color-Coded Conversations

Whether teaching ELA remotely or in person, Ashley Bible of Building Book Love makes it a point to provide ample opportunity for shy students to thrive. One of her go-to silent discussion strategies is a Color-Coded Conversation using a shared document.

- Set up a shared doc with a table that will fit all of your students plus the topics you want them to discuss. For example, a 4×30 table if you have 30 students and want to discuss three points.

- Instruct students to choose a UNIQUE color, font, or combo for their name. This specific color/font will follow them throughout the discussion.

- Have students give their points in their own boxes then move to other boxes to continue the conversation.

Students LOVE getting to choose their own font and colors while experiencing the novelty of multiple people typing on the same doc. Teachers benefit by being able to quickly scan and follow the color-coded contributors! You see this process in action on the second slide here and find more lively discussion strategies from Ashley here: How to Liven Up Your Socratic Seminar .

3. Human Bar Graphs

The human bar graph is a great way to immediately measure ELA students’ understanding of any topic in a fun, interactive game for the classroom or a Google Meet/Zoom.

How it works face-to-face:

Before social distancing, Emily from Read it. Write it. Learn it. used the Human Bar Graph by placing A, B, C, and D labels at the front of the classroom. Emily would display a question with four possible answer choices on her SmartBoard. These choices could be opinions (agree/disagree) or fact based (one correct answer) options. Students would then stand in a row at their answer forming a Human Bar Graph.

Virtual options:

Now, Emily uses the Human Bar Graph digitally. It takes some prep work, but once it’s done, you’ll have it to reuse over and over. You can save time by grabbing a pre-made version here .

To create a Human Bar Graph, open a Google Slide with a custom page setting of 8.5×11 inches. Post a question at the top and A, B, C, D answer choices at the bottom. Insert a rectangle just small enough for a student to write their name. Then, right click and copy and paste enough rectangles on the page for the number of students you have in class.

Share this slide with students through Google Classroom as an assignment using the Students Can Edit option. Once students are in the slide together (up to 50 can work together at one time), instruct them to write their name on one rectangle. That rectangle will be theirs to click and drag.

Now, the fun begins! Read a multiple choice question slowly and carefully so all students can hear the question and answer choices. Read answer choices a second time if necessary. Then, tell students to move their rectangles to choice A, B, C, or D.

To add drama and excitement, you could give students who volunteer the opportunity to place their rectangles and explain their thinking before letting the whole class loose!

After finishing your human bar graph, be sure to discuss patterns and what those patterns might reveal.

Beyond traditional multiple choice, the Human Bar Graph is also a great survey tool. Give students a statement and have them rank how much they agree or disagree (A = strongly agree; D = strongly disagree). Use the answer choices to share opinions about a text or topic. For example, A could represent The character survived because of luck . B could represent The character survived because of his own perseverance , etc.

Your students will love interacting in real time, and the discussions that follow will be rich!

4. Collaborative Note Catchers

If you’re looking for a way to facilitate and keep track of small group discussions, Shana Ramin from Hello, Teacher Lady recommends using Google Slides as a collaborative note catcher.

Simply create a slideshow with one slide for each small group and change the sharing permissions to “Anyone with the link can edit.” Once students have the link, they’ll be able to type on their group’s assigned slide as they discuss the prompt in small groups.

The best part? The slides are easy to monitor in real time using the Grid View in Google Slides. This allows teachers to see the overall discussion activity in one single view and check in on groups that may need additional prompting. You can learn more and grab Shana’s free note taker templates here.

5. Virtual Questions

If you’ve been searching for a platform for online discussion boards, the answer might be right in front of you: Google Classroom. While Classroom does not have a specific “discussion board” feature, Abby from Write on With Miss G has found a way to “hack” Google Classroom questions so they function as discussion boards.

When you use a Google Classroom question, students can reply to each other in the comments, which makes this feature a discussion board of sorts. Just make sure to check “ Students can reply to each other ” in the bottom right-hand corner (although it should default to this setting). You, too, can join your students’ discussion and ask guiding questions to move their conversation forward.

You can ask one essential question, give students a choice of questions to answer, or even ask students to submit their own questions for their peers to answer (like a virtual Socratic Seminar ). Whatever you do, you’ll want to make sure that you clearly communicate and model expectations for responding to peers so that students don’t end up merely commenting “I agree” and “Same, bro!”

While this strategy works well for fully virtual learning, it’s also a great option for traditional, flipped, or hybrid learning. You can start class with a silent, virtual discussion board, and then use students’ responses as a springboard for an in-class discussion. Or, you can assign a discussion board after a chapter of reading homework and let students learn from each other before you fill in the gaps during a whole-class discussion the following day.

These online discussion boards are powerful because they give all learners a voice in a low-risk setting. You can read more about how Abby structures and facilitates these online discussions HERE .

6. Google Form Groupings

Google Forms are such a simple and easy tool for teachers and students alike.

If you have not created Google Forms before, Lauralee walks you through the process in her digital classroom blog post.

Primarily, she uses Google Forms to organize students into groups; students answer one or two questions based on classroom studies. After you pose a question in the Form, decide how you’d like students to answer. You can choose a multiple choice, short answer, or longer essay option.

Lauralee typically provides multiple choice options. Then when students respond, she separates students into groups based on their similar ideas. Often, Lauralee creates a Google Slides presentation for each group that is labeled after the multiple choice responses.

Students can then collaborate in a virtual setting, and they already are familiar with the topic since they answered the question similarly. Google Forms are quick to make, and the data is simple to process (especially with the multiple choice and checkbox features), which makes it a time-saving tool.

CLASS DISCUSSION STRATEGIES: FORMATS

When it comes to configuring students into different formats (both virtually and in-person), the sky is the limit.

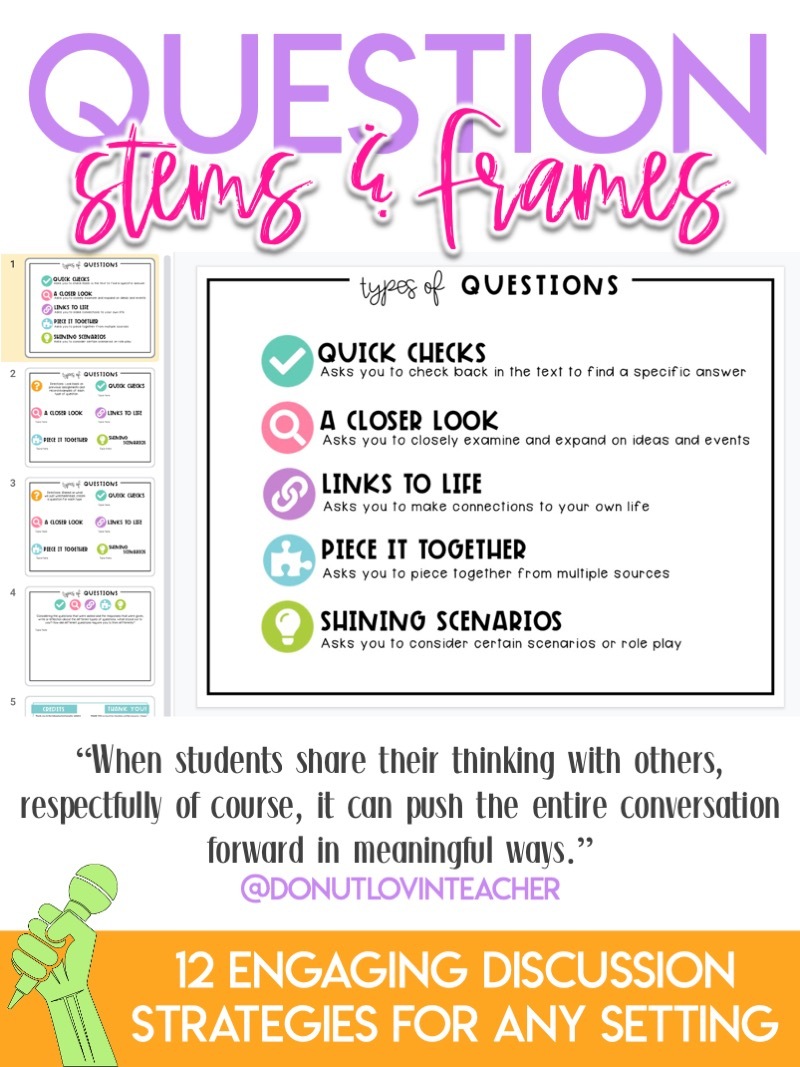

7. Question Stems + Sentence Frames

Have you ever sent students into a discussion and they were done in the blink of an eye? An integral aspect of any of these discussion strategies is student readiness.

Staci ( @DonutLovinTeacher ) often asks her students to engage in Socratic Seminars, digital discussion boards, or in Book Clubs. However, before expecting students to know how to have these kinds of discussions, Staci and her students examine the impact of types of questions and responses.

To better support all of her students, Staci has conversations with her students about types of questions. Staci shares different kinds of questions with her students and asks them to look through previous assignments to find examples. Based on a short video or text, they practice asking different kinds of questions and her students are able to see first hand how the questions lead to very different discussions.

Furthermore, Staci finds it valuable to provide and practice using different kinds of sentence frames that will help students “ think out loud. ” When students share their thinking with others, respectfully of course, it can push the entire conversation forward in meaningful ways. Leave these frames up in a digital or in-person setting for students to reference throughout the discussion. Sometimes a little preparation and support can go a long way!

Students need scaffolding. Quality discussion skills are often not intuitive. We can explicitly teach students about the nuances of eloquent conversations by scaffolding and modeling. Gradually, as students internalize these concepts and they become second nature, students will be more independent.

8. Gallery Walks

In the spirit of co-creating learning, Tanesha ( @love.tanesha ) uses gallery walks to engage students around essential topics and to build background knowledge.

There are several ways to organize gallery walks, which depend on the desired outcome and topic. Teachers can create gallery walks by arranging a mix of photos and images around the room in stations. Students are grouped and rotate between stations with a specific focus. One of the most important considerations is having enough rich content for students to engage with that invites divergent thinking and conversations.

Teachers can leverage this activity virtually using the same tactics, and leveraging breakout rooms, Google hangouts, or a similar tool for students to interact with one another.

One of the most inviting elements of a gallery walk is how it engages various learning styles and promotes independence . It’s a simple activity with tremendous outcomes for students. Tanesha has found that it works for her shy and outgoing students!

9. Panel Discussions

Inspired by a popular political show, Jenna (@drjennacopper) developed panel discussions as one of he favorite classroom discussion strategies. A panel discussion is made up of three roles: a moderator who asks questions (a student or the teacher), panelists (four to five students), and the audience (the rest of the class).

The moderator guides the discussion, and the panelists function as “experts” on the topics for discussion.

Like a fishbowl discussion, students rotate in and out of the panel positions throughout the discussion so everyone gets a turn as a speaker and a listener. (Students rotate out of the panel when they’ve fulfilled the speaking and listening requirements.)

To add another layer of complexity, the audience can partake in a virtual discussion to mimic “tweeting,” which often happens during panel discussion. Jenna uses a shared Google Doc or Backchannel Chat for her audience members.

All students are involved in the discussion. The variety of three different roles keeps things fresh. Teachers can be involved as little or as much as necessary, and throughout the year, they can scaffold panel discussions to full, student-led conversations.

To learn more about the steps for making students the experts in panel discussions, you can read more here .

10. Team Packs

It’s no surprise that kids love novelty, so when Staci from @theengagingstation handed her students these super fun, bright, and bubbly team packs, they were instantly intrigued.

In face-to-face instruction , these team packs are a great way to foster collaborative discussion. Simply print one question on a piece of paper and insert it into a team pack. Students will work together to answer the question, then pack up their team pack and pass it on to the next group. When the next group receives it, they must add to the discussion answers by adding more analysis, text evidence, conclusions, and more.

How can this work digitally ? Staci has found great success so far in the digital school year of using props. You can simply hold one of these fancy team packs on your camera display and pull out a question, or you could consider creating a Google Slide template that students can interactively click on to “open” the team pack (and it’ll take them to a slide with a question!).

Team packs are an easy way to add simple engagement. In just a short amount of time, students can answer several text-based questions, work collaboratively, revisit texts, and fall in love with shiny bubble mailers…or whatever packaging you choose to utilize.

You can read more about team packs and how Staci made them on her blog .

11. Socratic Seminar Variations

Socratic Seminar might be one of the most important instructional discussion strategies that an ELA teacher can learn and implement in her classroom. The driving force of a socratic seminar? INQUIRY.

To develop a seminar, Amanda from Mud and Ink Teaching recommends starting with an Essential Question. Essential Questions are questions that guide units of study and illicit genuine curiosity and further inquiry from students (check out this blog post for a head start or her course to learn more!).

Once you have your question written, you’ll need to find texts that all speak to the question, and the more variety, the better! A novel study, art, TED Talks, poetry, and nonfiction are all texts that students can read and interpret ahead of time and then bring into the seminar discussion when it’s time.

Once students are prepared with the EQ, any smaller sub questions, and the texts, it’s time to invite them into the discussion.

Face-to-Face: To host a socratic seminar in the classroom, arrange desks in a circle and discussion begins (this Teaching Channel video is an amazing starting place!).

Virtual: Amanda has also hosted her socratic seminars using Google Docs and the platform Parlay with great success.

No matter the platform or design, what makes socratic seminars so powerful, is that the students are the only ones doing the talking, the answering, and the leading. The teacher’s job is to sit at the periphery of the room, take anecdotal notes, and listen for the conversation to naturally build and deepen in complexity as it carries on.

Socratic seminars take practice, but Amanda promises that the more often her class does them, the better they get every time! If you need inspiration for your questions and texts, Amanda has you covered !

12. Fishbowl Discussions

One way that Christina, The Daring English Teacher , loves to get students engaged in meaningful classroom conversations is through fishbowl discussions . She holds fishbowl discussions every semester to provide students with an opportunity to discuss what they’ve learned during the semester.

To set up a fishbowl discussion, she places two tables facing each other in the center of the classroom and then rearranges all of the other tables in a big circle around the two tables. Essentially, she creates a fishbowl.

Students then volunteer to go into the center of the fishbowl to answer the discussion questions. It is good to have four students enter the fishbowl at a time so that they can discuss each question and engage in a back-and-forth conversation as they answer the question.

To tie the discussion back to classroom content, The Daring English Teacher makes sure that the students not only answer the question, but they must also provide examples or evidence. This way, students can build off of one another with multiple examples to answer one question.

This discussion strategy can easily be modified to fit online formats. To modify the fishbowl discussion virtually, teachers can use this digital Socratic Seminar Google resource to help students engage in a meaningful, socially-distanced or Zoom classroom conversation.

Students can volunteer to join the discussion, and as they discuss the questions (which can also be posted in the chat feature), the students who are listening can take notes about what each speaker says and contributes to the discussion.

And that makes TWELVE meaningful teacher- and student-tested conversation modes for middle and high school students. We hope you find this big list of classroom discussion strategies helpful for whatever unique challenges you are facing this year.

10 ELA Lesson Plans that Engage Students Any Time of Year

10 creative ela lesson strategies, literary analysis activities to elevate thinking.

Get the latest in your inbox!

IMAGES

VIDEO