- Place order

How to Integrate a List of Things in an Essay or Paper

In academic writing, all papers must follow strict formatting rules and structures. Essays, research papers, term papers, dissertations, theses, or reports are written in APA, MLA, Harvard, Chicago, or Oxford, among other formatting styles. With the structure comes some rules to maintain, and one of these rules is how to incorporate lists when writing.

Lists are ideal even when writing in prose, even if they abruptly disrupt the structure, design, length, and sometimes grammar of the written piece. They can be integrated into the prose (horizontally or run-in) or set vertically depending on the amount of information and its intended purpose.

What is in a list? You may ask .

A list makes your work easy to read without struggling to identify the main points. They make your format recognizable and your reading digestible.

If you use the right punctuation, syntax, and grammar and stick to the formatting style requirements, you are good at including lists in an essay or any academic writing task. However, you must know that you can only use a vertical list if there are more than three items, and anything less than that should not be listed and should follow the general sentence formatting rules.

Let us see how everything works and how to present a list in an essay.

Types of Lists in Academic Writing

You can format lists differently, provided they are parallel and consistent. In academic writing, there are two types of lists: run-in lists and vertical lists, and let us expound on the meaning and formats of each.

Run-in Lists

A run-in list is a list that is included as part of the general text, and they are laid out in line in running prose. It is a horizontal list that entails listing the items as part of the sentences in a paragraph using the correct punctuation. In APA, you can use seriation within sentences where an item in the sentence is preceded by a number or letter enclosed in two brackets, followed by a semicolon, and has a period at the end of the sentence. Let’s look at an example:

Based on post-world cup analysis research conducted by sports researchers, it emerged that (a) it united more people than ever; (b) created a sense of belongingness for football fans; (c) broke the fear caused by the Covid-19; (d) helped entertain millions of fans; (e) contributed to Qatar’s GDP.

You can introduce run-in lists through a complete sentence followed by a list of items preceded by a colon while a comma separates each item. Let us look at an example:

Every camper and hiker should be introduced to basic survival skills training so that they can: make a fire without flint or matches, forage food, track and navigate the wild, make simple tools, and manage emergency scenarios.

On the same note, the list can also be part of a sentence where each item is separated by numbers or letters in paragraphs. Let us look at an illustration.

Kids should train for and participate in triathlons because it: (1) keeps them active, (2) teaches them to set and meet goals, (3) helps them develop motor skills, and (4) develops strength, endurance, and balance.

Vertical Lists

Vertical lists are laid out vertically and can be ordered and labeled with numbers or letters or bulleted (unordered).

A vertical list is preceded by a complete sentence that gives a brief introduction or overview of the items or points in a list. Vertical lists do not necessarily have to be bulleted, nor do you require to put a punctuation mark at the end of each item in the entry.

Making a camping fire is a fun process that involves the following:

- Have a source of water, a bucket, and a shovel

- Gather enough wood for the fire

- Pile a handful of tinder at the center of the fire pit

- Kindle the fire and add more wood

When your lead-in sentence is complete, and all the entries comprise complete sentences, you can use a final period at the end of each item in the list.

When you have a long list that cannot be presented in a single sentence, use vertical lists that are punctuated as a sentence. You can use this structure when the phrases have internal punctuation, or the reader might have trouble getting the gist of your written text.

If you have a complex vertical list, you can format it like an outline. You can then use numbers or letters to itemize the items in the list. The lead-in or introductory sentence should be a complete sentence followed by a colon.

Vertical lists help improve readability by breaking blocks of prose or chunks. They also help the readers to skim the text with ease, and they also highlight important content. Finally, they can be used as a signpost or to cue the readers about the following content, especially when listing subheadings or sections.

Ensure that you observe the nuanced rules for punctuating vertical lists for every formatting style you use to write an academic paper.

When to Use Lists in an Essay or Paper

Even though lists can disrupt the formatting, grammar, and structure of an essay or a written piece, they are sometimes the necessary evil that makes such papers organized. Imagine reading a prose format text that has stuffed a list of items in a sentence, and you must read, interpret, or internalize. It would be a tough call, won’t it? That’s where lists come in. Lists are meant to get your reader’s attention so they can decode your message on the go and off the bat. You can use lists in an essay when:

- Introducing a cluster of ideas

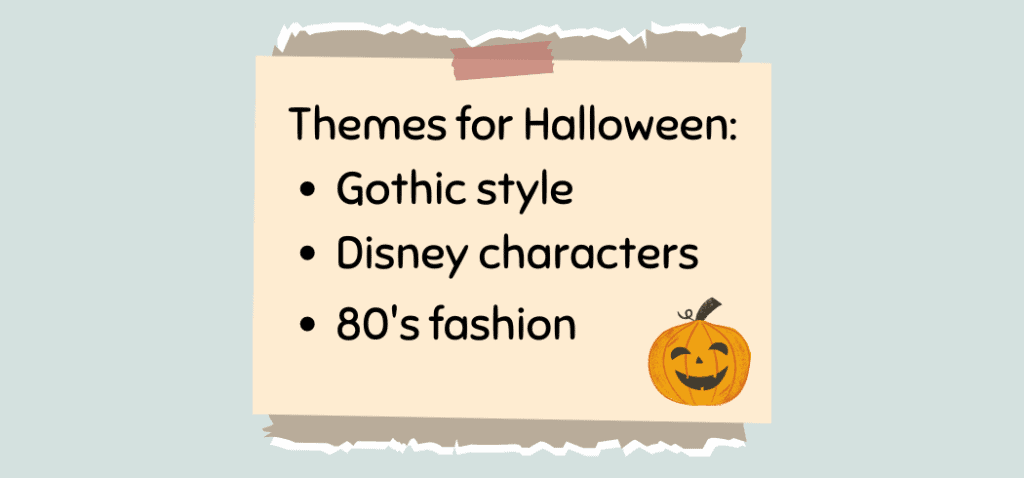

- Including themes

- Writing subtopics

- Writing an assessment/evaluation checklist

- Steps in a process or analysis (procedures, strategic planning or project planning, nursing SOAP Notes, etc.)

- Components of an item (list of board of directors, recipes, etc.)

- Signposting the ideas in your written piece

- List of recommendations

- Help navigate longer lists such as data sets

That said, you must adhere to parallelism and punctuation to the T when creating a list in an essay or any academic writing task. Besides, you must pay attention to the general formatting guidelines for the respective formatting style you are writing the paper.

Different Ways to List Items in an Essay

When assigned to write an essay or research paper in MLA, APA, Chicago, or Harvard formatting styles and you need to make a list, you should only proceed when it is unavoidable. Combine the list with good transition words, and you will make comprehensive, coherent, and cogent paragraphs that make your writing stand out.

That said, many ways to list items in an essay include using a numbered list, bulleted list, lettered list, and running text lists. Even though these means are allowed, you can only use lists sparingly in your writing.

1. Bulleted or Unordered Lists

Bulleted lists are a preference when using lists that do not communicate hierarchical, superiority, priority, or chronological order. Although sparingly, you can use bulleted points in academic writing when:

- Formulating recipes and introducing component lists.

- Listing items

- Emphasizing points after an interpretation

- Clarifying the step-by-step process

- Condensing descriptions

- Providing evidence to support arguments and claims

- Illustrating points

- Providing examples

If opportunity allows, you are highly encouraged to use bullet lists in a research paper to make it readable as long as there is no condition to the list. If you have lists that are not too long, have them as separate paragraphs. You can also introduce short bulleted lists as titled sections. But if you have longer items to list and want to be thorough in your listing, use a bulleted list.

Before introducing the bullet list, ensure that you have an opening sentence explaining the list's contents. The introduction should give your readers a head start on the items, so they are not confused as they read.

When including the bulleted lists, indent them at least one inch or one tab stop from the left margin. The lists should be double or single, depending on the entire document's general spacing.

You cannot use a bulleted list in an academic essay or paper when:

- Writing the conclusion of your paper

- Writing the thesis statement

- Writing the introduction paragraph

The use of bullet points is strictly prohibited in these circumstances. You can use bullet lists in quotations, as we share later in this article.

Related Reading: Transition words and phrases to use in a university essay .

2. Numbered or Ordered Lists

Like bullet point lists, you can use numbered lists that are similar, only that the latter has numbers instead of bullet points. Besides, there are also rules to observe when using either.

Most formatting styles, such as MLA and APA, allow seriation (use of numbered or ordered lists). However, this should be done sparingly as well. Overusing the numbered lists will make your paper look more like an outline than an academic piece written in prose.

You should use numbered lists when describing a series of events or a logical arrangement of items. Every list begins with numerals and ends in a full stop/ period.

If you are integrating the list in prose, you need to use colons and bracketed numbers.

The main steps of taking a shower include: (1) getting your clothes off, (2) getting into the bathroom; (3) activating the shower and adjusting to the right temperature, and (4) taking a bath.”

Notice that you must open and close the parentheses and not use just one bracket.

You can also use a semicolon and bracketed numbers if your pieces of evidence have a comma in the middle, and Semicolons are used to separate the elements. Alternatively, you can make a vertical list rather than a run-in text to better capture readers' attention.

You can also list items by specifying their order. This is the first, second, third…nth.

3. List with Letters

Lettered lists are like numbered lists in every aspect. Listing things in an essay using letters and brackets entails using lowercase letters within parentheses preceding the items in the list, followed by semicolons before introducing the next item. The second last item will have the semicolon and the word “and” or “or” before introducing the last item and finishing with a period.

The main steps of taking a shower include: (a) getting your clothes off, (b) getting into the bathroom; (c) activating the shower and adjusting to the right temperature, and (d) taking a bath.

4. Running Text Lists

Ever heard of the famous Oxford comma? You can use it in a sentence to introduce a list of items in an essay within run-in texts, and the serial comma precedes the conjunction.

When you plan a hike, you must pick a safe destination, get good gear, have the right attitude, prepare well, and plan your trip.

Making Lists in APA formatting Style

APA formatting style, used primarily in social sciences, allows using both numbered and bulleted lists. You should consult with your instructor whether to include lists in your essay or piece of assignment for clarity so that you submit work that meets instructions.

In APA style, you can list with bullets if you want to separate points in a sentence. In this case, the list is not preceded by a colon, and the bulleted list is considered part of the sentence. This option is usually great when writing complex sentences that might be difficult to digest without punctuation. If the bulleted list contains phrases rather than sentences, there is no need for punctuation.

As an example:

The project planning team has assessed the suitability of the location and has already completed

- the impact assessment report;

- health and safety report;

- work breakdown structure;

- letters of request;

- soil testing report as illustrated in their final letter.

In APA 7, using numbered lists is encouraged for complete sentences or paragraphs in a series. You can, for instance, use a numbered list when describing steps in a procedure or including itemized recommendations.

In APA 7, you have two options for punctuating bulleted phrases: to include no punctuation after each list item and after the last list item or to include commas or semicolons, as appropriate, after each list item and final punctuation at the end of the list. Example:

- the impact assessment report

- health and safety report

- work breakdown structure

- letters of request

Here is an example of a seriated list in APA

A survey should include (a) clear wording, (b) convenient access, (c)concise direction, and (d) simple language.

If you list three or more items, use a serial comma or Oxford comma before the last item and the conjunction “and’ or “or.” If you have one or more clauses that contain commas, you should use a semicolon instead of a comma to separate every clause.

Also Read: Signposting strategies for essays and papers .

How to make a List in MLA Format

In MLA style, primarily used in humanities subjects, there are many ways to integrate a list.

First, you can integrate a list into your essay's prose or paragraphs. In this case, the lists are introduced by the text.

E.g., “ We can praise Baldwin for his astute sociological observations, crafting meticulous sentences, and using metropolitan dialogue.”

Instead of using commas, you can also list using a colon.

For example, “ Baldwin is known, primarily, for three reasons: astute sociological observations, meticulous crafting of sentences, and using decidedly metropolitan dialogue.”

You can also introduce a vertical list in MLA either as a complete sentence or a list that continues the sentence that introduced it.

If you introduce a list by a complete sentence in the body, it should end in a colon first, then introduce the list as complete sentences or fragments. In this case, the first letter of each item in the list must be capitalized if they are a complete sentence. Besides, you should adhere to the punctuation rules for sentences.

Having gone through the report, four pertinent questions arise:

- Are we prepared for the future?

- Are our competitors edging us out of the market?

- Do we have the capacity to counter competition?

- When can we begin implementing new mechanisms to counter the effects we are seeing now?

You can also stratify some sentences in your MLA-format paper into a vertical list, and the lists will be considered as one single sentence.

In this case, since it is a sentence continuation, there is no need to include a colon before the list. Instead, begin the sentence as usual and format each item on a separate line.

Every item in the list ends in a semicolon. The second last item should have a semicolon and the word “or” or the word “and. The final item should have a closing punctuation of the sentence.

Several schools are reconsidering their physical security setups by

- installing motion sensors;

- installing gates with access controls;

- hiring guards with military training;

- only allowing authorized vehicles into the school; and

- Log in to all the people who enter and leave the school digitally.

If you can avoid using numbered lists in MLA, please do so without hesitation.

Using Bulleted Lists with Quotes and Paraphrased Text

You can use bulleted lists to format paraphrased passages from a source. You need to use a signal phrase or citation in the sentence before the text. For example:

“Red and yellow are the best colors to decorate a restaurant because they induce feelings of hunger, energize customers to order more food, and prevent patrons from lingering in the dining area once they have finished their meals.” (Jackson, 2009)

This can be paraphrased as:

It is profit-oriented to decorate a restaurant with yellow and red colors. Jackson (2009) suggests

- make people feel hungry;

- lead to customers eating and therefore spending more;

- and encourage diners to leave the restaurant once they have finished eating, freeing the tables for new customers.

A bulleted list can also function as a block quote, without quotation marks, if taken directly from the source. However, you must introduce the source with a signal phrase, and the quote should be single-spaced. If you change any words, you need to use brackets. You should also include the citation in the list item after the period after the last thing in the list.

Sticking to the same original passage, the right way to present this would be:

In her marketing study, Jackson highlights the benefits of decorating a restaurant with red and yellow color schemes citing that these colors,

- induce (potential customers’) feelings of hunger,

- energize customers to order more food, and

- prevent patrons from lingering in the dining area once they have finished their meals. (Jackson, 2009, p. 29)

You can also use the bulleted list to quote individual list items directly and paraphrase some items. Again, you must use the signal phrase or citation in the paragraph preceding the list. You should also include quotation marks and citations with the quotes in verbatim. Taking the same example:

When it comes to restaurant décor, the findings of a marketing study by Jackson (2009) suggest that the colors red and yellow:

- Make people feel hungry.

- “Energize customers to order more food.” (Jackson, 2009, p. 29)

- Encourage diners to leave the restaurant once they have finished eating, freeing the table for new customers.

Dos and Don’ts when Using Lists

As you strive to perfect listing items or things in an essay or paper, there are some things you should do and others that you should not do. Even though we have listed them as part of this guide, in the previous sections, let us gather them together for clarity. Below are some things you should do and others not to do with lists in academic writing:

- Only group items that are related. As you write and edit lists in your essay or academic writing, ensure they belong together. Only give a list of items related to the paragraph, sentences preceding it, or those it is part of. If the things are unrelated, disband the list and use other strategies.

- Your list should be easy to read. Instead of slapping everything else into your list, ensure it is structured and easy to read. The intention is to get the main idea out to your readers without them wasting much time. The list should be introduced well and straightforwardly. If there is a grammatically complex item, place it at the end of the list for easy processing.

- Observe punctuation rules. Every academic writing style guide has a unique approach and the best ways to use either numbered or bulleted lists. You must adhere to punctuation styles, including a colon, semicolon, or period. The punctuation should be consistent and correct. If unsure, ask your instructor for clarification.

- Stick to the grammatical rules. As you write the lists in your essay or paper, ensure that you observe grammatical rules such as capitalization rules.

- Do it Sparingly . Your academic writing must demonstrate that you can comprehensively research, synthesize, and present facts about a specific topic or subject. Depending too much on lists can dilute the very purpose resulting in a subpar essay or paper. If there is an opening to use them, do it sparingly and only when unavoidable. You are not doing a PowerPoint slide and do not want your essay to look like a scatter graph. Draw meaningful connections using prose format that entails good flowing words, sentences, and paragraphs.

As you Exit….

Again, we insist that using numbered or bulleted items or points in academic writing should only be made when unavoidable.

- How to write a perfect academic essay .

- How to use quotes in essays and papers.

The rationale is that formal academic writing entails synthesizing information and critically presenting arguments to explore in-depth topics, which can only be achieved with uninterrupted prose: complete sentences and paragraphs.

Capitalizing the items in a list depends on whether you are writing complete sentences or the list is part of a sentence in a paragraph. You can capitalize the first letter of the first word of the items in the list if you are writing a complete sentence where you don’t need a semicolon but a full stop or period at the end of each item.

Need a Discount to Order?

15% off first order, what you get from us.

Plagiarism-free papers

Our papers are 100% original and unique to pass online plagiarism checkers.

Well-researched academic papers

Even when we say essays for sale, they meet academic writing conventions.

24/7 online support

Hit us up on live chat or Messenger for continuous help with your essays.

Easy communication with writers

Order essays and begin communicating with your writer directly and anonymously.

How to Write a List Correctly: Colons, Commas, and Semicolons

If you want to write a list but aren’t sure about the correct punctuation, look no further. In this article, you’ll learn how to appropriately use colons, commas, and semicolons when making lists.

- Colons are sometimes used to introduce a list.

- Commas separate items in a simple list.

- Semicolons are used to separate items in a complex list.

How to Write a List Correctly

For writers, list-making is a handy tool to illustrate your ideas or to make your text more readable by breaking it up.

There are two types of lists: horizontal and vertical. Each type uses colons, commas, and/or semicolons.

A Punctuation Review

Before we dig in, let’s review what colons, commas, and semicolons are.

Colons look like this:

Commas look like this:

Semicolons look like this:

Horizontal Lists

Horizontal lists help you give examples or specify your argument by having ideas laid out next to each other.

Colons, commas, and semicolons come in handy when it comes to laying out your list and making it look neat. But what are the standard guidelines?

Using Colons in a List

First of all, the colon. It can be used to introduce lists but isn’t necessary. Your list can be a simple continuation of your sentence.

For instance:

The available colors are blue, gray , and white.

You should use a colon, though, if you use an apposition (e.g., “the following”).

The available colors are the following: blue, gray, and white.

You should also use a colon to introduce a list if semicolons separate the items in the list:

The available colors are: blue and gray; black and white; and red and pink.

Later I’ll explain whether to choose commas or semicolons to separate the items in your list.

Using Commas in a List

Use commas to separate items in a simple list - that is, if each item comprises a single word.

The following sentence illustrates this:

For lunch, you can have a toastie, salad, or fries.

Using Semicolons in a List

You can use semicolons to separate items in complex lists - that is, if each item comprises several words or contains the conjunction ‘and.’

If you use semicolons to separate the items, you must also introduce the list with a colon.

I’ll show you what I mean.

For lunch, you can have: a cheese and ham toastie; a caesar salad; or french fries with ketchup .

Because each separate item contains several words, and sometimes the word ‘and’ it could be confusing to the reader if they were only separated with commas.

It’s by no means necessary to do this and perfectly acceptable to use commas still, but it’s just a way to make your list easier on the eye.

Vertical Lists

Vertical lists are a great way to make items stand out or to break up your text by making it more visually appealing. They are usually made with bullet points, numbers, or letters.

A common problem with vertical lists is deciding which punctuation to use at the end of each item.

Here are some easy-to-follow guidelines:

- Put a comma at the end if the items are unpunctuated single words or phrases.

- Use a semicolon at the end if the items are punctuated but aren’t complete sentences.

- If the items are complete sentences, use a full stop at the end as you usually would when writing a regular sentence.

The last item in your bulleted list needs a full stop. You can look at the bulleted list above as an example of a vertical list that uses full sentences.

Here’s an example of a vertical list with unpunctuated single words or phrases:

The top three things we look for in a Masters Student candidate are

- motivation,

And here’s an example of a vertical list with punctuated clauses or phrases:

The plan for this evening is to go:

- to the restaurant for dinner;

- dancing with friends;

- have the happiest birthday .

To introduce a list, use a colon if the items are complete sentences that stand alone. If it’s just a clause or phrase, use no punctuation, and imagine the bulleted list as being a continuation of the sentence.

Top Tip! If you’re writing some kind of brochure or creative document, you can take more freedom with the punctuation since your goal is to make it look as appealing and readable as possible.

Concluding Thoughts on How to Write a List Correctly

I hope this article has helped you feel more confident about using punctuation when writing lists. Let’s summarize what we’ve learned:

- Use commas to separate items in a simple list.

- Use semicolons to separate items in a complex list.

- Use colons to introduce a list after an apposition or semicolons to separate the list items.

If you found this article helpful, check out our blog archive on navigating complex grammar rules.

Learn More:

- 'Dos and Don'ts': How to Write Them With Proper Grammar

- How to Write a Movie Title in an Essay or Article

- How to Write Comedy: Tips and Examples to Make People Laugh

- ‘Spicket’ or ‘Spigot’: How to Spell It Correctly

- How to Write Height Correctly - Writing Feet and Inches

- Assertive Sentence Examples: What is an Assertive Sentence?

- Optative Sentence Example and Definition: What Is an Optative Sentence?

- Grammar Book: Learn Basic English Grammar

- How to Write a Monologue: Tips and Examples

- ‘Writing’ or ‘Writting’: How to Spell It Correctly

- How to Correctly Apply 'In Which', 'Of Which', 'At Which', Etc.

- ‘Goodmorning’ or ‘Good Morning’: How to Spell ‘Good Morning’ Correctly

- ‘Realy’ or ‘Really’: How to Spell ‘Really’ Correctly

- ‘Eachother’ or ‘Each Other’: How to Spell ‘Each Other’ Correctly

- 'Do' or 'Does': How to Use Them Correctly

We encourage you to share this article on Twitter and Facebook . Just click those two links - you'll see why.

It's important to share the news to spread the truth. Most people won't.

Add new comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

How to Properly List Things in a Sentence

| Danielle McLeod

Danielle McLeod

Danielle McLeod is a highly qualified secondary English Language Arts Instructor who brings a diverse educational background to her classroom. With degrees in science, English, and literacy, she has worked to create cross-curricular materials to bridge learning gaps and help students focus on effective writing and speech techniques. Currently working as a dual credit technical writing instructor at a Career and Technical Education Center, her curriculum development surrounds student focus on effective communication for future career choices.

Lists are a popular way for people to stay organized. Perhaps you jot down grocery items or tasks you need to complete at work each day on a sticky note or your phone. But, when you need to communicate lists in writing and speech, you need to organize them in a manner to show importance and clarity to your audience.

Items aren’t the only thing you can make a list of either: ideas, claims, directions, and even complicated storylines can be integrated into a list format.

The biggest challenge I encounter when teaching English is how to punctuate list items properly. Let’s look at how to write a sentence with a list below and where and when to use punctuation, so your information is clear to your reader.

What is the Best Way to Write a List?

When jotting down some quick list items for your eyes only (such as a simple grocery list), you probably don’t care what your lists look like. But list format matters when you have an audience.

Listing things in a sentence can contain simple items, such as what you might pick up from a store. Or a list might illustrate complicated directions or ideas to help support a claim. No matter the content, organization and punctuation matter , as does the proper grammar for listing items.

There are two types of lists: vertical and horizontal. Both are very useful and communicate ideas effectively when used in the proper context.

When to Use Vertical Lists

Vertical, bulleted lists are great to use when you need to make a very visual point concerning your list items. This style of organization is best used for emails and memos that are formal but brief and very specific in the information being shared. It also works great to help break larger sentences into something quick and easy to view.

For example:

- A copy of your licensure certification

- Your available transportation dates

- A list of all students attending

- An overview of your trip itinerary

- The objectives of the lesson associated with the trip

It is also good for providing formal yet understandable directions.

- 4 lbs of flour

- 1 dozen eggs

- 1 can each of baking soda and baking powder

- 12 packets of yeast

- 1 block of sharp cheddar cheese

- 2 lbs fresh jalapeno peppers

Vertical lists are also the preference for a quick, informal item listing for personal use.

Grocery List

When to Use Horizontal Lists

Horizontal lists are best used when writing out more complicated ideas in paragraph form. They work well for quick lists and are also the preference for writing dialog. These can be used in both formal and informal writing, especially when sharing complicated ideas or thoughts.

- My frustration with the students had to do with their complete apathy toward the material, their disregard for wasted time, and their inability to realize how their actions were affecting their future.

- I need you to run to the store to pick up a few items: milk, butter, eggs, and bread.

- On our road trip, we passed through Fort Worth, Texas, where we spent a day at the Stockyards; Orlando, Florida, to visit my brother and his family; and Garden City, South Carolina, because I have a condo there.

How to Punctuate a List in a Sentence

Knowing the correct punctuation for list items is very important to avoid running your items together and creating a jumble of words. Lists not only use commas to separate items but also use colons and semicolons when the occasion arises.

Comma List Rules

If you list three or more words, prepositional phrases, or clauses in a series, you need to use a comma to separate them. The comma placed between the final two items is called an Oxford (or serial) comma . Some people feel this is an unnecessary punctuation mark, but its use helps provide a visual separation to avoid confusion.

Use Commas to Separate Three or More Words

Commas separate words in a simple list of items to ensure your reader that they are separate items and not the same thing.

- After work, I need to run to the grocery, laundry, and daycare.

Use Commas to Separate Three or More Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional phrases add detail to your sentence’s main topic. Commas help separate these details to create understandable information.

- Mykayla won the scholarship due to her detailed essay writing, her intrinsic motivation, and her interview preparation.

Use Commas to Separate Three or More Clauses

Clauses are detailed and consist of multiple words. A comma creates organization and structure, so your reader understands the information you share.

- The high school marching band was plagued by many disappointments over the weekend when the bus they were traveling on got a flat tire, the competition they were performing in rained out after the first round, and the trip home took twice as long due to the rain.

When Not to Use a Comma

If your list items are already separated by coordinating conjunctions or you list pairs of items, you don’t have to use commas between them.

- I went to the farm store for chicken and horse and dog food.

- I love to make bacon and eggs, biscuits and gravy, and toast and jelly for breakfast.

Colon List Rules

Colons follow an independent clause to connect the information that follows with the main topic. When a colon introduces a list, what precedes it must be a complete sentence, even if the list is vertical.

Use a Colon to Introduce a List Horizontally

Horizontal lists are lists that are integrated into the sentence following the colon placement.

- The school drill went flawlessly: everyone was organized, students stayed quiet, and the meeting place made it easy to take a head count.

Use a Colon to Introduce a List Vertically

If you use a colon to introduce a vertical list, you still need to place it after a complete sentence. Vertical lists work well for simple lists, or to list fragments when creating horizontal lists may create confusing or long sentences.

- A choice of hot or iced coffee

- Homemade breakfast pastries

- Sandwiches made to order

Use a Colon to List Abbreviations

You can also use colons to list abbreviations.

- MI: Michigan

- SYP: Student Youth Program

When NOT to Use a Colon

Colons should not be used after headings, titles, or captions to introduce information. There are many other options you can use to indicate formatting.

- Indentations

- Underlining

- Color changes

Semicolon List Rules

Semicolons are used to conjoin two complete sentences related to one another. It can also replace a comma and coordinating conjunction pair to avoid the repetitive use of and .

When used to separate list items, semicolons help create a division between elements that already include a comma. This can be as simple as city and state combinations or work to help clarify complex lists that contain descriptive instruction.

Use a Semicolon to List Locations

Semicolons are used to punctuate complex lists that include cities, states, and countries. Since commas are necessary to properly punctuate locations, a semicolon is needed if more than one is used in a series.

- I’m using my vacation days this year to road trip through Moab, Utah; San Francisco, California; Portland, Oregon; and a stop to ski in Banff, Alberta, Canada before heading back home.

Use a Semicolon to Divide Events

Descriptive events that contain a comma should be separated by a semicolon if they are listed within a sentence.

- Our trip to the Kennedy Space Center included a walking tour of the shuttle Atlantis, which is on display in the memorial building; a break in the Planet Play Zone, where children are immersed in space exploration; and an astronaut training experience, a real-life encounter with astronaut training scenarios.

Use a Semicolon for Descriptive Instructions

If your sentence includes detailed, punctured instructions, you will need to separate these steps using a semicolon.

- Before our field trip on Friday, I need you all to complete the following information in advance: one, your physical health release; two, your physics worksheet on forces; three, your confirmed group members complete with contact information.

Use a Semicolon to Provide Detail

When including descriptive elements in your list items, you should include semicolons if the descriptions are already punctuated.

- The luncheon included ham, turkey, and vegetable finger sandwiches with delicate cheeses; fresh melons, strawberries, and grapes with a sweet dipping sauce; and a choice of decadent fruit sorbets, tartlets, or hand-dipped chocolates for dessert.

When NOT to Use a Semicolon

Do not use a semicolon to replace a comma unless the list item that follows already includes comma punctuation. Also, do not use a semicolon to replace a colon. Semicolons do not introduce a list.

Let’s Review

Including lists in your writing to create descriptions and detail is an excellent way to create varied sentence structure. Although you don’t want to depend upon it too heavily, there are many ways to punctuate your items when you begin to include phrases and clauses within your list organization.

Grammarist is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. When you buy via the links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission at no cost to you.

2024 © Grammarist, a Found First Marketing company. All rights reserved.

Writing from Near and Far

Transform Your Travels Into Meaningful Memoir

How to Write a List Essay

If you’re feeling stuck with your travel memoir writing, an interesting and playful structure to try is to tell your story in the form of a how-to list. This structure is like an instruction manual, but humorously reframes each step as part of your story. Some example titles might be:

How to Not Get Deported in Singapore How to Get Your Heart Broken in Hanoi How to Get Over Sea Sickness in Greece How to Become a Lifelong American Expatriate

What would your title be?

Let’s think about an example: If you had a life changing experience on a boat ride down the Ganges River, your title might be ‘How to be Profoundly Moved on the Ganges River’. You might start out with: “1. Decide to book a flight to India. Change your mind. Change it back. Ask your friends if you’re making the right decision. Listen to your husband telling you, ‘Just go. It’s not that big of a deal.”

As you can see, this type of essay is written in the second person. That means you’ll be using ‘you’ in place of ‘I’, and writing in the imperative voice (giving commands) rather than unfolding a traditional tale.

This type of essay will also include numbers for each ‘step’ in your how to guide. I suggest not having too many steps. Between 5 and 15 is a good range to aim for. Some steps can be longer than others—they don’t necessarily need to be of similar lengths.

Still going with our example, the rest of ‘How to be Profoundly Moved on the Ganges River’ could focus on your transition from ambivalence to profound experience as you spend time on the river, meet the others on the boat with you, and make stops along the way.

These steps could start something like this:

“Meet Chris from Idaho on the walk up to the temple. He tells you …”

And “Walk next to Daveed, your guide. Decide to listen closely to everything he says about …”

And “Avoid stray dogs at all costs. You read about this in the guide books, but acting upon this advice is different than reading. You love dogs, but you must suppress this love for now.”

Obviously I’m just making up these examples to help you get some ideas for your own how to essay.

Even if you’ve written about a particular trip in the past in a more traditional way, this structure can help you reframe that experience and write it from a different angle. This kind of structure is also great for online publications, since so much of what we read online these days is comprised of lists. This how to structure gives the impression of a light, quick read. And your interpretation of this kind of essay can certainly fit that, but it can also be dense and profound, only masking as light Internet fodder.

Take a look at this example from the Agni review titled Breakup Tips.

Even though Breakup Tips is not travel themed, it is still a great (and quick) example of a how to essay that reaches for profound over light. Almost every sentence starts with an imperative: “Stand,” “Draw,” “Wait,” “Pull,” “Find,” etc. It’s a good idea to start most of your numbered sections with a command word to pull off the conceit that this is an instructional text.

I’ve also published one of these essays, mentioned as an example above: How to Become a Lifelong American Expatriate . Writing my story as a how to guide allowed me to give a broad overview of my travels and moves to different countries over the years, all masked as instructions to the reader. The appealing and humorous aspect of these kinds of essays is the suspended belief that any of these lists could ever actually exist as an instruction to someone else, when of course they couldn’t. That’s what makes it fun, and potentially profound. When we push ourselves to tell our stories in unconventional forms, magic can happen.

If you start to write this, I’d love to read it! Send me an email with your draft, and I’ll give you some helpful feedback.

Share this:.

- Click to share on Threads (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

MLA Formatting Lists

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Note: This page is new and reflects added guidance published in the latest version of the MLA Handbook (i.e., MLA 9).

Though they should be used sparingly, lists are a great way to convey information in an easily digestible and recognizable format. Lists are either integrated into the prose or set vertically, dependent on the list’s purpose and the amount of information presented.

INTEGRATED INTO THE PROSE

Lists that are integrated into the text can be introduced by text itself:

Baldwin was known for his astute sociological observations, meticulously crafted sentences, and decidedly metropolitan dialogue.

Or they can be introduced with a colon:

Baldwin was known, mainly, for three things: his astute sociological observations, meticulously crafted sentences, and decidedly metropolitan dialogue.

SET VERTICALLY

There are a number of ways to properly format a vertically set list. Numbered lists should only be used when the nature of the list necessitates a specific order.

LISTS INTRODUCED BY A COMPLETE SENTENCE

Lists can be introduced by a sentence in the body, which should end with a colon. The items can be complete sentences or fragments. The first letter of each list-item must be capitalized if the items are complete sentences. Each sentence requires punctuation.

Keeping with Cabral’s teachings, we must ask the following questions while interacting with social issues:

Do our solutions consider the stated needs of the community we are speaking for?

Do we have a clear strategy?

Do we have realistic expectations?

If the items are not complete sentences, they should be bulleted or numbered. These should also be introduced with a colon at the end of a sentence. In both formats, begin each item in lowercase. Bulleted items do not require punctuation. Numbered items, beyond their respective numbers, should follow the same guidelines as a list-item that continues the sentence that introduces it (detailed below).

LISTS THAT CONTINUE THE SENTENCES THAT INTRODUCED THEM

Some sentences can be stratified into vertically-set lists. These lists should be considered, technically, as one single sentence. Do not introduce the list with a colon. Simply begin the sentence as you normally would and then format each item onto a separate line. End each item with a semicolon, closing the second-to-last item with a semicolon, followed by the word “and” or the word “or”. End the final item with the closing punctuation of the sentence.

Several health-food stores are focusing on customer safety by

requiring that essential oil manufacturers include skin irritation warnings on their bottles;

documenting the temperature of all frozen produce upon arrival; and

performing all mopping after hours, in order to prevent accidents.

Bullet items that continue sentences do no not require punctuation, nor do they require a colon to introduce them.

How to List Things in an Essay

Lists are essential components of essays because they make the paper easier to read and understand. Whether you are writing guides, recipes, academic papers, or informational articles, including lists is a good writing practice.

Nevertheless, lists can distort your paper’s structure, so you need careful consideration when listing things in your essay. So, how do you do it and balance between aesthetically improving your piece and, at the same time, not overdoing it?

Generally, a list is a form of presentation that helps to organize ideas orderly. It also provides information in an easy-to-read format. This makes it easier for your readers to understand what you are trying to convey.

In this post, we will go over the different types of lists that you can use when creating your essay, as well as when and why you should use them.

Importance of Listing Things in an Essay

You might be wondering why we need to use lists. A list helps you organize information, break up long paragraphs and make information easier to understand. Lists can also be used to make reading easier and more enjoyable.

Generally, the following are the benefits of listing things in an essay.

It gives your essay a better structure

A list is a simple but powerful device for organizing and presenting the information. Using a list in your essay gives the paper a strong structure and makes it easy to read.

Further, using lists in your essay can help you organize your ideas clearly and logically, which in turn, makes them easier to follow by the reader. In addition, because some papers may contain many points, lists make such articles more manageable for readers by breaking up large amounts of text into smaller chunks that are easier to digest.

It engages and gives readers a better memory

Listing is a great way to engage your readers. It’s easy for them to remember the points you make because they are in a list rather than in prose. If you have three or four main points in your essay and want them to stand out, and be memorable to the reader, listing them is an ideal route.

When you use lists, it makes it easier for the reader to follow what you are saying one by one. Lists are also helpful in organizing information and ideas you want to share and making them more memorable.

It helps you prioritize your points

Listing things in an essay helps you prioritize and make your strong points first, then finish with less crucial points. This is because you can easily follow through on listed points rather than in a paragraph.

This is also true for readers because you want to convince them at the start rather than wait until the end.

As highlighted, a list is a common way to present information in an essay. They help readers understand the ideas in your writing without much struggle.

In general, lists help you organize information or give a complete picture of something. For example, if you’re writing about how much time your family takes to do daily chores, you might list the time each of the following activities takes.

- Cleaning the bathroom

- Taking out the trash

- Washing dishes

The following are some of the common ways on how to list things in an essay.

Using a bulleted list

Bulleted lists are a great way to organize your thoughts and make them easy for the reader to follow. They’re also easy to write, so if you’re struggling with an idea for your essay, try keeping things simple by listing everything out instead of trying to explain it in paragraphs.

You can use bulleted lists anywhere in your essay—the beginning or end, or even as a transition between paragraphs.

Bulleted lists can make any paper look more professional and organized, but they’re handy when writing research papers because they allow professors and graders to quickly skim through an essay and get a sense of what important points you’re trying to make.

A bulleted list is ideal for a typical list of items, such as people’s names and ingredients.

For example, you can have a recipe with the following listed items

Using Arabic numbers

Use Arabic numbers when you want to list things out of order. For example, if you wanted to write about the ingredients mentioned above, your list will look as follows

The Arabic numbers can be followed by a period, as shown, or by a parenthesis.

Using lowercase letters

Lowercase letters are another way to list items in an essay. The format follows the Arabic format, either a period or a parenthesis.

Using capital letters

Capital letters are another great way to list items in your essay. It entails using capital letters in alphabetical order, followed by a dot or parenthesis.

Using a numbered list

A numbered list involves listing your items using numbers. This method is effective if you are explaining the steps of a process.

As with any other method, you can write the numbers followed by a period or a parenthesis. For example, if you are writing about installing a specific software, your list will look as follows

- Visit the software’s company download page or any other reliable page

- Download the software

- Run it on your computer and install

If you decide to use parenthesis, your list will look as follows.

In-text lists

Listing items within a text is another option for students and writers to list things. However, it is not apparent to every reader, but it is still considered a list.

For example, if your essay is on factors that cause environmental pollution, within a paragraph, you may write, ” motor vehicle fumes, greenhouse gases, industrial waste, and agricultural chemicals.”

- Numbered in text

This is another option but similar to the in-text list. The only difference is that the list is numbered.

For example, factors that lead to environmental pollution are ” 1) motor vehicle fumes, 2) greenhouse gases, 3) industrial waste, and 4) agricultural chemicals.”

Dos and Don’ts in Lists

These are some rules to follow when listing things in an essay.

Ensure your items in a list belong together

This is the most fundamental principle to follow when listing items. Ideally, every list should include like-minded items.

For example, if listing steps to do something, do not include ingredients in the list as part of the steps.

Make the list easy to read

Essentially, lists are meant to make your essay easy to read and appealing. Therefore, if your list contains chunks of text, it does not serve the purpose.

Also, if there is a technical and complex aspect in the list, ensure it comes in the end. However, it does not mean it can’t start, but if it is possible, save it till the end to avoid confusing your readers.

Use a sentence to introduce a list

In most cases, lists, especially vertical ones, have a sentence introducing them. This is essential as it helps readers know a list will follow and also serves as a good transition.

For horizontal lists, a dash can suffice, although it is considered informal.

Use the right punctuation

Punctuation is a critical aspect of lists. And if you want to stand out, you must follow the required punctuation rules when listing items.

If you use a verticle list, your items must be introduced by a colon. However, in horizontal lists, it is not necessary.

Other exceptions to the colon requirement are if you use the words namely, including, and such as. Additionally, the colon is unnecessary if your list flows smoothly.

Semicolons are another punctuation used in lists. They are used if the list is complex and when an item has a comma within itself. Similarly, a comma is another standard list separator and is used in simple lists.

In addition, the semicolon and comma are used before the word ‘and’ and the last item on the list. This is commonly known as the serial comma, although it is not used in the British and Australian English dialects.

This post has highlighted several ways of listing things in an essay. But remember that one method is not necessarily better than another, but the best approach will often depend on the specific type of list involved and the specific criteria for each task.

In addition, the most critical element will always be your ability to identify what you are writing about and create a good list for the reader. Further, when listing things in your essay, it is essential to develop them effectively so that your professor will have no trouble understanding your ideas.

Nevertheless, it’s important to remember that not all essays need lists. And despite this, lists are useful when presenting more than one, explaining a process or if many different points need further explanations.

How do I incorporate lists into my essay in MLA style?

Note: This post relates to content in the eighth edition of the MLA Handbook . For up-to-date guidance, see the ninth edition of the MLA Handbook .

In humanities essays, lists are generally run into the text rather than set vertically. A colon is often used to introduce a run-in list:

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has written four novels: Purple Hibiscus , Half a Yellow Sun , The Thing around Your Neck , and Americanah .

But no colon is used before a list when the list is the object of the verb that introduces it:

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novels include Purple Hibiscus , Half a Yellow Sun , and The Thing around Your Neck.

The list is the object of the verb include .

COMMENTS

Different Ways to List Items in an Essay. When assigned to write an essay or research paper in MLA, APA, Chicago, or Harvard formatting styles and you need to make a list, you should only proceed when it is unavoidable. Combine the list with good transition words, and you will make comprehensive, coherent, and cogent paragraphs that make your ...

Use bullets to list items when order is unimportant. As always, provide a sentence to introduce the list to follow. Bulleted lists must warrant the use of space, meaning do not use bullets for a list of two to four small items. The reader may assume you are wasting space to make your essay appear longer.

The last item in your bulleted list needs a full stop. You can look at the bulleted list above as an example of a vertical list that uses full sentences. Here's an example of a vertical list with unpunctuated single words or phrases: The top three things we look for in a Masters Student candidate are. education, motivation, grades.

When writing a list, ensure all items are syntactically and conceptually parallel. For example, all items might be nouns or all items might be phrases that begin with a verb. Most lists are simple lists , in which commas (or semicolons in the case of lists in which items contain commas) are used between items, including before the final item ...

Grocery List. Milk; Butter; Eggs; Bread; When to Use Horizontal Lists. Horizontal lists are best used when writing out more complicated ideas in paragraph form. They work well for quick lists and are also the preference for writing dialog. These can be used in both formal and informal writing, especially when sharing complicated ideas or ...

As you can see, this type of essay is written in the second person. That means you'll be using 'you' in place of 'I', and writing in the imperative voice (giving commands) rather than unfolding a traditional tale. This type of essay will also include numbers for each 'step' in your how to guide. I suggest not having too many steps.

Though they should be used sparingly, lists are a great way to convey information in an easily digestible and recognizable format. Lists are either integrated into the prose or set vertically, dependent on the list's purpose and the amount of information presented.

Lists are essential components of essays because they make the paper easier to read and understand. Whether you are writing guides, recipes, academic papers, or informational articles, including lists is a good writing practice. Nevertheless, lists can distort your paper's structure, so you need careful consideration when listing things in your essay.

In humanities essays, lists are generally run into the text rather than set vertically. A colon is often used to introduce a run-in list: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has written four novels: Purple Hibiscus, Half a Yellow Sun, The Thing around Your Neck, and Americanah. But no colon is used before a list when the list is the object of the verb that introduces it:

Harvard College Writing Center 5 Asking Analytical Questions When you write an essay for a course you are taking, you are being asked not only to create a product (the essay) but, more importantly, to go through a process of thinking more deeply about a question or problem related to the course. By writing about a