- Search Search Please fill out this field.

The Case for Paying College Athletes

The case against paying college athletes, the era of name, image, and likeness (nil) profiting, legal action against the ncaa, the bottom line, why college athletes are being paid.

In 2024 the NCAA signed off on a proposal to pay student athletes, but challenges remain

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Headshot-4c571aa3d8044192bcbd7647dd137cf1.jpg)

Thearon W. Henderson / Getty Images

Should college athletes be able to make money from their sport? When the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) was founded in 1906, the organization’s answer was a firm “no,” as it sought to “ensure amateurism in college sports.”

Despite the NCAA’s official stance, the question has long been debated among college athletes, coaches, sports fans, and the American public. The case for financial compensation saw major developments in June 2021, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the NCAA cannot limit colleges from offering student-athletes “education-related benefits.”

In response, the NCAA issued an interim policy stating that its student-athletes were permitted to profit off their name, image, and likeness (NIL) , but not to earn a salary. This policy will remain in place until a more “permanent solution” can be found in conjunction with Congress.

Meanwhile, the landscape continues to shift, with new cases, decisions, and state legislation being brought forward. In 2024, the NCAA signed off on a proposed settlement in response to a class-action anti-trust lawsuit. If finalized, the deal would see the NCAA pay out nearly $2.8 billion to 14,000 current and former student-athletes over the next decade, starting as soon as fall 2025. However, the proposed deal would allow schools to pay out athletes in the future, but would not require it.

College athletes are currently permitted to receive “cost of attendance” stipends (up to approximately $6,000), unlimited education-related benefits, and awards. A 2023 survey found that 67% of U.S. adults favor paying college athletes with direct compensation.

Key Takeaways

- Despite the NCAA reporting nearly $1.3 billion in revenue in 2023, student-athletes are restricted to limited means of compensation.

- Although college sports regularly generate valuable publicity and billions of dollars in revenue for schools, even the highest-grossing college athletes tend to see only a small fraction of this.

- One argument for paying college athletes is the significant time commitment that their sport requires, which can impact their ability to earn income and divert time and energy away from academic work.

- Student-athletes may face limited prospects after college for a variety of reasons, including a high risk of injury, fierce competition to enter professional leagues, and lower-than-average graduation rates.

- The practical challenges of determining and administering compensation, as well as the potential impacts on players and schools still need to be worked out.

- A settlement proposed in 2024 between the NCAA and the five biggest conferences (the Big Ten, Big 12, ACC, SEC, and Pac-12) would allow schools to pay athletes, but wouldn't require it.

There are numerous arguments in support of paying college athletes, many of which focus on ameliorating the athletes’ potential risks and negative impacts. Here are some of the typical arguments in favor of more compensation.

Financial Disparity

College sports generate billions of dollars in revenue for networks, sponsors, and institutions (namely schools and the NCAA). There is considerable money to be made from advertising and publicity, historically, most of which has not benefited those whose names, images, and likenesses are featured within it.

Of the 2019 NCAA Division I revenues ($15.8 billion in total), only 18.2% was returned to athletes through scholarships, medical treatment, and insurance. Additionally, any other money that goes back to college athletes is not distributed equally. An analysis of players by the National Bureau of Economic Research found major disparities between sports and players.

Nearly 50% of men’s football and basketball teams, the two highest revenue-generating college sports, are made up of Black players. However, these sports subsidize a range of other sports (such as men’s golf and baseball, and women’s basketball, soccer, and tennis) where only 11% of players are Black and which also tend to feature players from higher-income neighborhoods. In the end, financial redistribution between sports effectively funnels resources away from students who are more likely to be Black and come from lower-income neighborhoods toward those who are more likely to be White and come from higher-income neighborhoods.

Exposure and Marketing Value

Colleges’ finances can benefit both directly and indirectly from their athletic programs. The “Flutie Effect,” named after Boston College quarterback Doug Flutie, is an observed phenomenon whereby college applications and enrollments seem to increase after an unexpected upset victory or national football championship win by that college’s team. Researchers have also suggested that colleges that spend more on athletics may attract greater allocations of state funding and boost private donations to institutions.

Meanwhile, the marketing of college athletics is valued in the millions to billions of dollars. In 2023, the NCAA generated nearly $1.3 billion in revenue, $945.1 million of which came from media rights fees. In 2023, earnings from March Madness represented more than 80% of the NCAA’s total revenue. Through this, athletes give schools major exposure and allow them to rack up huge revenues, which argues for making sure the players benefit, too.

Opportunity Cost, Financial Needs, and Risk of Injury

Because participation in college athletics represents a considerable commitment of time and energy, it necessarily takes away from academic and other pursuits, such as part-time employment. In addition to putting extra financial pressure on student-athletes, this can impact athletes’ studies and career outlook after graduation, particularly for those who can’t continue playing after college, whether due to injury or the immense competition to be accepted into a professional league.

Earning an income from sports and their significant time investment could be a way to diminish the opportunity cost of participating in them. This is particularly true in case of an injury that can have a long-term effect on an athlete’s future earning potential.

Arguments against paying college athletes tend to focus on the challenges and implications of a paid-athlete system. Here are some of the most common objections to paying college athletes.

Existing Scholarships

Opponents of a paid-athlete system tend to point to the fact that some college athletes already receive scholarships , some of which cover the cost of their tuition and other academic expenses in full. These are already intended to compensate athletes for their work and achievements.

Financial Implications for Schools

One of the main arguments against paying college athletes is the potential financial strain on colleges and universities. The majority of Division I college athletics departments’ expenditures actually surpass their revenues, with schools competing for players by hiring high-profile coaches, constructing state-of-the-art athletics facilities, and offering scholarships and awards.

With the degree of competition to attract talented athletes so high, some have pointed out that if college athletes were to be paid a salary on top of existing scholarships, it might unfairly burden those schools that recruit based on the offer of a scholarship.

‘Amateurism’ and the Challenges of a Paid-Athlete System

Historically, the NCAA has sought to promote and preserve a spirit of “amateurism” in college sports, on the basis that fans would be less interested in watching professional athletes compete in college sports, and that players would be less engaged in their academic studies and communities if they were compensated with anything other than scholarships.

The complexity of determining levels and administration of compensation across an already uneven playing field also poses a practical challenge. What would be the implications concerning Title IX legislation, for example, since there is already a disparity between male and female athletes and sports when it comes to funding, resources, opportunities, compensation, and viewership?

Another challenge is addressing the earnings potential of different sports (as many do not raise revenues comparable to high-profile sports like men’s football and basketball) or of individual athletes on a team. Salary disparities would almost certainly affect team morale and drive further competition between schools to bid for the best athletes.

In 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the NCAA violated antitrust laws with its rules around compensation, holding that the NCAA’s current rules were “more restrictive than necessary” and that the NCAA could no longer “limit education-related compensation or benefits” for Division I football and basketball players.

In response, the NCAA released an interim policy allowing college athletes to benefit from their name, image, and likeness (NIL) , essentially providing the opportunity for players to profit off their personal brand through social media and endorsement deals. States then introduced their own rules around NIL, as did individual schools, whose coaches or compliance departments maintain oversight of NIL deals and the right to object to them in case of conflict with existing agreements.

Other court cases against the NCAA have resulted in legislative changes that now allow students to receive “cost of attendance” stipends up to a maximum of around $6,000 as well as unlimited education-related benefits and awards.

The future of NIL rules and student-athlete compensation remains to be seen. According to the NCAA, the intention is to “develop a national law that will help colleges and universities, student-athletes, and their families better navigate the name, image, and likeness landscape.” However, no timeline has been specified as of yet.

In 2020, former Arizona State swimmer Grant House and former TCU/Oregon basketball player Sedona Prince filed an antitrust lawsuit against the NCAA for refusing to allow NIL payments for athletes prior to 2021. They claimed that the five biggest conferences (the ACC, the Big 10, the Big 12, the Pac-12, and the SEC) work in tandem with the NCAA to exploit the labor of student-athletes and limit the compensation that they can receive, and that the NCAA's limitations on NIL and their control over TV markets obstructs athletes from receiving their fair share of market value.

The NCAA was also involved in two other antitrust cases, Hubbard vs. the NCAA and Carter vs. the NCAA, seeking damages on behalf of athletes.

In July 2024, formal settlement documents were filed with the Northern District Court of California to resolve all three cases. If finalized, the deal would see the NCAA direct nearly $2.8 billion to 14,000 current and former student-athletes over the next 10 years, with payments beginning as soon as fall 2025. However, while the proposed deal would allow schools to pay out athletes in the future, it would not require it. Other important details are yet to be determined as well, such as whether the new compensation model would be subject to Title IX laws.

In their official statement, the A5 conference commissioners and NCAA president expressed the following: "This is another important step in the ongoing effort to provide increased benefits to student-athletes while creating a stable and sustainable model for the future of college sports. While there is still much work to be done in the settlement approval process, this is a significant step toward establishing clarity for the future of all of Division I athletics while maintaining a lasting education-based model for college sports, ensuring the opportunity for student-athletes to earn a degree and the tools necessary to be successful in life after sports."

However, they also noted that the settlement "does not resolve the patchwork of state laws, many of which may conflict with the settlement," and that "these laws will need to be preempted by federal legislation in order for the settlement to be effective."

Why Should College Athletes Be Paid?

Common arguments in support of paying college athletes tend to focus on players’ financial needs, their high risk of injury, and the opportunity cost they face (especially in terms of academic achievement, part-time work, and long-term financial and career outlook). Proponents of paying college athletes also point to the extreme disparity between the billion-dollar revenues of schools and the NCAA and current player compensation.

Is It Illegal for College Athletes to Get Paid?

Although the NCAA once barred student-athletes from earning money from their sport, the rules around compensating college athletes are changing. In 2021, the NCAA released an interim policy permitting college athletes to profit off their name, image, and likeness (NIL) through social media and endorsement and sponsorship deals. In 2024, the NCAA reached a settlement on a series of anti-trust lawsuits that, if approved, would pay out nearly $2.8 billion in damages to current and former athletes and allow them to be paid in the future. However, current regulations and laws vary by state.

What Percentage of Americans Support Paying College Athletes?

In 2023, a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults found that 67% of respondents were in favor of paying college athletes with direct compensation. Sixty-four percent said they supported athletes’ rights to obtain employee status, and 59% supported their right to collectively bargain as a labor union .

The NCAA is under growing pressure to share its billion-dollar revenues with the athletes it profits from. In 2024, they reached a proposed settlement to address three different anti-trust lawsuits, which, if approved, would have them pay out nearly $2.8 billion in damages to current and former student-athletes, and would change the guidelines around how, and how much college athletes should be paid.

Many of the implications of these changing policies are still unclear, but future rules and legislation will need to take into account the financial impact on schools and athletes , the value of exposure and marketing, pay equity and employment rights, pay administration, and the nature of the relationship between college athletes and the institutions they represent.

NCAA. “ History .”

Marquette Sports Law Review. “ Weakening Its Own Defense? The NCAA’s Version of Amateurism ,” Page 260 (Page 5 of PDF).

U.S. Supreme Court. “ National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston et al. ”

NCAA. “ NCAA Adopts Interim Name, Image and Likeness Policy .”

AP News. " Paying College Athletes Is Closer Than Ever. How Could It Work and What Stands in the Way? "

NBC. " NCAA Signs Off on Deal That Would Change Landscape of College Sports - Paying Student-Athletes ."

PBS NewsHour. “ Analysis: Who Is Winning in the High-Revenue World of College Sports? ”

Sportico. “ 67% of Americans Favor Paying College Athletes: Sportico/Harris Poll .”

Sportico. “ NCAA Took in Record Revenue in 2023 on Investment Jump .”

National Bureau of Economic Research. “ Revenue Redistribution in Big-Time College Sports .”

Appalachian State University, Walker College of Business. “ The Flutie Effect: The Influence of College Football Upsets and National Championships on the Quantity and Quality of Students at a University .”

Sportico. " NCAA's Cash Cow Remains (for Now) Amid Wholesale Change ."

Grand Canyon University. “ Should College Athletes Be Paid? ”

Flagler College Gargoyle. “ Facing Inequality On and Off the Court: The Disparities Between Male and Female Athletes .”

U.S. Department of Education. “ Title IX and Sex Discrimination .”

Congressional Research Service Reports. “ National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston and the Debate Over Student Athlete Compensation .”

NCSA College Recruiting. “ NCAA Name, Image, Likeness Rule .”

Duke University Chronicle. " Breaking Down the House v. NCAA Settlement and the Possible Future of Revenue Sharing in College Athletics ."

NCAA. " Settlement Documents Filed in College Athletics Class-Action Lawsuits ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1560435740-e3620f71f9bf497c9ecbe83f8c5aadf6.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Economists recommend paying college athletes

The current compensation arrangement for big-time college athletics is inefficient, inequitable and very likely unsustainable, according to a new study by economists from the University of Chicago and Vanderbilt University. The article concludes that an evolution to a competitive labor market with fewer restrictions on pay for top athletes may be inevitable, though the transition will be difficult.

In their study released this week in the Winter 2015 issue of Journal of Economic Perspectives , Allen Sanderson, senior lecturer in economics at UChicago, and John Siegfried, professor emeritus of economics at Vanderbilt, write that the practice of setting a binding limit on remuneration for student-athletes – grant-in-aid restricted to room, board, tuition, fees, and books – may violate the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The authors argue that payment caps set by the NCAA are holding down benefits that otherwise would go to top-performing athletes, many of them African Americans from low-income families, while top coaches and athletic department personnel receive disproportionately high salaries.

Instead, the researchers recommend, schools should compensate student-athletes according to the value they provide, whether that value comes in the form of measurable revenue or more subjective benefits.

Sanderson said recent proposals by the NCAA to shift from single-year to multiyear scholarships, and to cover unrestricted meal plans and other incidental out-of-pocket costs for players, fall well short of a free competitive labor market.

Such proposals “are mainly an attempt by the NCAA to stay one town ahead of the sheriff," Sanderson said.

In addition to exploring the labor market for college athletes, the paper, entitled “The Case for Paying College Athletes” also examines why U.S colleges and universities operate large-scale commercial athletic programs, with a focus on men’s football and basketball. The authors question the rationale among many universities that such big-time programs subsidize their money-losing intercollegiate sporting ventures.

The Student-Athlete Debate

Since athletes have historically been considered students rather than employees, they have not been covered by general labor laws, says the study. Therefore, they cannot bargain collectively via union representation, nor can they apply for workers compensation.

As a result, university athletic departments can essentially dictate many aspects of a student-athlete’s routine and engage them in long hours of practices, something that might not be possible if they had to obey general labor laws. The study claims that the NCAA is allowed to maximize its profits by steadily expanding regular-season and playoff/bowl games since the marginal operating cost is minimal.

For example, the study notes that college football started a four-team playoff in January 2015 without reducing the number of regular-season games. There are already calls to expand the football playoffs to eight or even 16 teams. Television exposure has also led to an increased number of games played at neutral sites, where both teams must travel, as well as games played on weeknights during the academic year.

“The players have no voice in these decisions to expand the schedule, and no claim on the incremental revenues generated,” said Sanderson.

Additionally, minimum age requirements in the National Football League and the National Basketball Association restrict alternatives available to prospective college athletes, according to the study. Such restrictions give the NCAA virtually total control over the labor market for players. Moreover, the NCAA makes it difficult for student-athletes to transfer to another institution that might be a better fit.

Such labor practices have led to a series of legal challenges. The authors list several high-profile pending lawsuits, which they believe could result in “an evolution well beyond the incremental steps taken by the NCAA.”

One case, O’Bannon vs. NCAA, would do away with wage fixing, allowing schools to pay players up to $5,000 per year of eligibility. Another involves an appeal before the National Labor Relations Board by Northwestern University, which has petitioned the body to reconsider a regional director’s recognition of Northwestern football players as university employees.

“These lawsuits and pressures from the regulatory bodies could ultimately reduce, if not completely eliminate the monopoly power of the NCAA, the intercollegiate sports teams, and conferences,” says Sanderson.

Redirecting Scarce Academic Funding to Sports

Contrary to the popular belief that intercollegiate athletics is profitable, the study notes that according to NCAA data, only one out of every six of the Football Bowl Subdivision universities earned a profit in 2013, a typical year, and only a portion of those profits were transferred to the academic side of their universities.

A USA Today report in 2013 also found that over $1 billion of student tuition and fees was transferred annually to athletic departments in NCAA Division I to support intercollegiate sporting ventures.

None of those institutions’ charters mentions commercial entertainment activities in their mission statement, said Sanderson. But when they incur financial losses on athletics, officials spend more on “salaries for coaches and improving physical facilities rather than interpreting losses as a signal to redeploy assets elsewhere.”

The study notes that academic institutions subsidize athletics “with a combination of mandatory student fees, scarce general institutional funds, public monies from state governments, and contributions solicited from alumni and well-heeled donors that might have been directed to other academic purposes or toward reducing the seemingly perpetual escalation of tuition costs in higher education today.”

The authors dispute the rationale for such subsidies, that success in intercollegiate athletics attracts larger state appropriations and private donations from alumni who might view a university more favorably, and the presence of high-profile athletic programs attracts additional applicants. Citing numerous studies and data, the study says any such gains are "meager" and fleeting."

The future of college sports

The researchers envision an arrangement where student athletes receive labor law protections, competitive compensation and more thorough medical coverage. In most cases this would require more subsidies from the school’s general fund and force university leadership to have soul-searching conversations about how much the school is ultimately willing to charge its student body to subsidize an intercollegiate sports program. It would also create Title IX implications, as there are far fewer women in revenue-generating college sports than men. Whatever happens, the researchers write, “It seems unlikely that the landscape of big-time commercialized intercollegiate athletics 10 years from now will resemble today’s incarnation, or anything seen in the last half-century.”

Liz Entman at Vanderbilt University contributed to this article.

Top Stories

Uchicago fourth-year student named 2025 rhodes scholar, uchicago celebrates opening of john w. boyer center in paris.

- UChicago scientists study how the environment is silently shaping your risk for cancer

Get more at UChicago news delivered to your inbox.

Related Topics

Latest news.

Global Impact

Big Brains podcast

Big Brains podcast: Can we predict the unpredictable? with J. Doyne Farmer

Meet A UChicagoan

Unraveling the ancient past, one tablet at a time

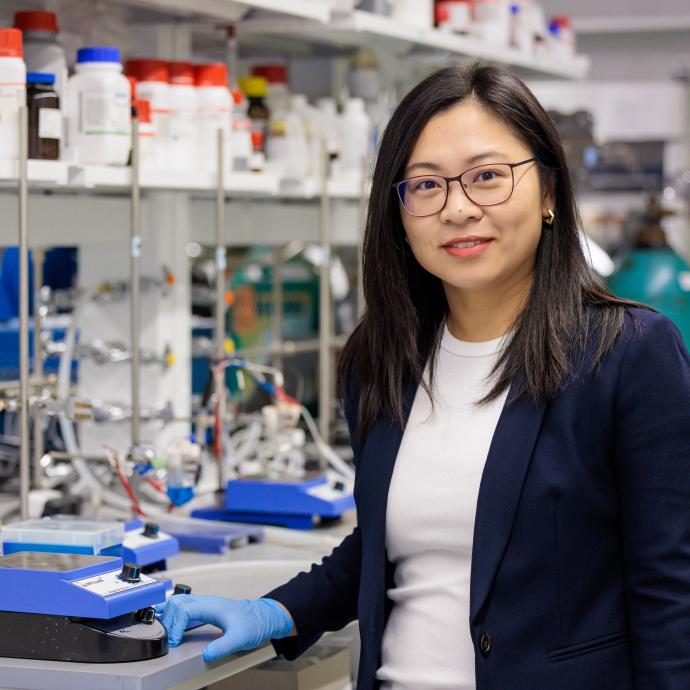

Go 'Inside the Lab' at UChicago

Explore labs through videos and Q&As with UChicago faculty, staff and students

Materials Science

In bioelectronics breakthrough, scientists create soft, flexible semiconductors

Telescopes and Cosmos

Latest findings from the South Pole Telescope bolster our model of the universe

Around uchicago.

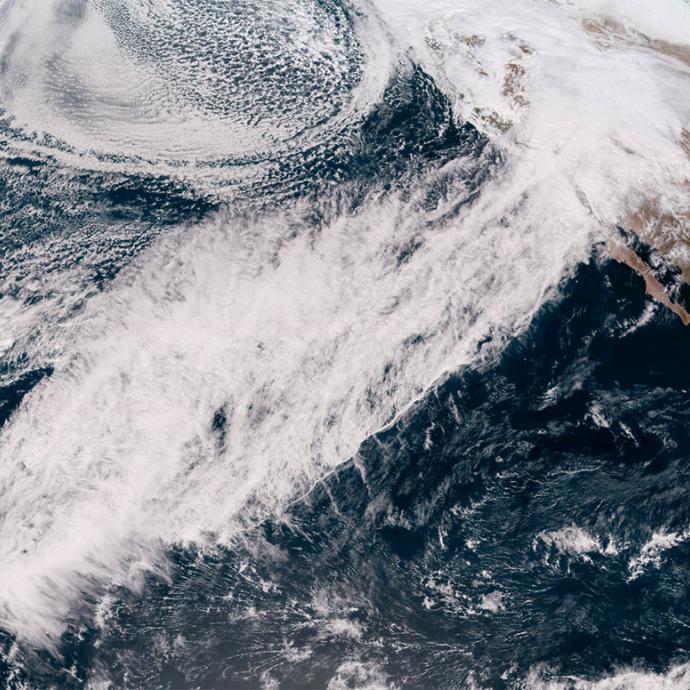

Geophysical Sciences

UChicago scientist develops new paradigm to predict behavior of atmospheric rivers

Selwyn rogers elected to national academy of medicine.

UChicago Medicine

$75 million donation from AbbVie Foundation to support UChicago Medicine’s new …

New Program

UChicago offers new master’s program in environmental science

Materials science

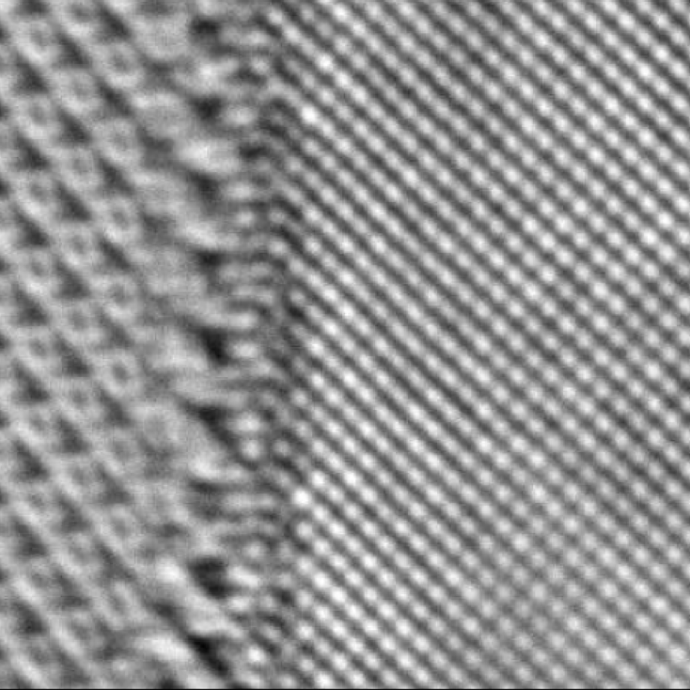

UChicago scientists invent a way to bond diamond layers for quantum devices

UChicago scientists invent faster method to make advanced membranes for water filters

Film History

“Throughout my time at UChicago, I’ve sought to provide opportunities to share scholarship with the public”

Rhodes Scholar

UChicago fourth-year student named Rhodes Scholar

IMAGES