- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Writing Tips Oasis - A website dedicated to helping writers to write and publish books.

How to Describe a Hospital Room in a Story

By Brittany Kuhn

Is a hospital room a setting in your book? If you’re wondering how to describe a hospital room in a story, we’ve put together 10 words and short pieces of narrative making use them for you below.

1. Clinical

- Relating to a hospital patient.

- Methodical or calmly detached.

- With exact precision.

“Even the posters on the wall were more clinical than comforting. It was less a room and more a doctor’s office with a bed.”

“The clinical instruments crowded around the bed made her look less human and more like a robot.”

How it Adds Description

Describing a hospital room as clinical suggests your character feels the hospital doesn’t see them as a person, only a job. Clinical makes the room feel more like a laboratory for research than a place of healing and adds a sense of dread to the scene.

Completely cleaned of all life or micro-organisms.

“He hated how sterile his hospital room felt; even the smell of the cleaning liquid echoed how completely lifeless it was.”

“I looked around and immediately noticed how sterile and void of life the room felt; how could my mother hope to fight for her life here?”

Sterile is a natural word to use when describing a hospital room because it suggests a lack of germs or dirt, things to avoid if you don’t want to cause an infection. However, sterile also implies a place completely empty of personality or variety, which you could use to echo your character’s feelings of hopelessness about being there in the first place.

- Without coverings; exposed.

- Without superfluous additions, just the necessities .

“The room was bare apart from a bed, a sink, and a singular uncomfortable chair.”

“She started adding her own touches to the bare hospital room. If she was going to be there a while, might as well make it hers.”

Use bare to describe the hospital room to give your reader some specific insight into how the character is feeling about the situation. Having your character describe the room as bare shows the character is feeling as empty and disconnected as the room physically seems.

Oppressive feeling of being closed in .

“With no fan or window to open, the hospital room began to feel increasingly stuffy and stifling.”

“He had been lying in the hospital bed for so long the air around him felt stuffier with every breath.”

If you really want to hammer home how trapped your patient feels, have them describe the hospital room as stuffy . A stuffy hospital room implies a mood of panic and anxiety hanging in the air and gives a negative impression of whatever procedures might be taking place there.

5. Comfortable

- Providing a sense of safety and relaxation.

- Without doubt or worry.

“Her mom added some soft bits from home to help the room feel more comfortable for the long haul.”

“The nurses have added little touches, like fresh flowers and personal notes on the whiteboard, to make the room more comfortable compared to the rest of the hospital.”

Alternately, someone who has come to terms with the situation or a more advanced or wealthy hospital might have more comfortable rooms. Using more positive language like comfortable shows the reader that this hospital likely leads to more successful outcomes.

- For single or restricted use.

“When they wheeled me into my own private room, I didn’t know whether to rejoice from the privacy or be worried at the special treatment.”

“We always knew the patient was terminal when they got moved to the private , secluded room on the third floor.”

Describing your character’s hospital room as private, shows the reader that they need more specific and specialized medical attention. A private room also suggests the character is unlikely to be leaving the hospital anytime soon.

Small and tightly packed.

“All the life-saving instruments he needed to stay alive made the room seem cramped and crowded.”

“Even though there was only a bed and a bedside table, the cramped hospital room felt fit to burst.”

Cramped suggests a claustrophobic atmosphere for a character, caused by not knowing when they will ever leave the hospital room again. Cramped can also highlight how small the room is if you are commenting on the poor state of the hospital or care.

Lacking in color or vibrancy, such as snow or a bright light.

“She was practically blinded by how white the hospital room was; it was like she’d died and gone to the pearly gates.”

“The dark red of the patient’s blood seemed even more alien splattered all over the white walls of the hospital room.

Making a point of how white the hospital room looks will highlight for the reader just how empty of color and life the room feels. This also suggests feelings of death, like when those who have died for a few minutes say they saw a white light. The reader will feel anxious for the character in the hospital because the whiteness of it all will feel too much like the character is about to die.

Without sound or movement.

“It was eerie how quiet and empty the hospital room was in the middle of the night.”

“The hospital room was surprising quiet once they turned off the machines keeping him alive.”

Hospitals are loud places: there are alarms going off, people rushing around, doctors barking orders. Describing a hospital room as quiet shows that something has gone wrong and will make the reader sit up and pay attention to whatever is happening.

10. Overwhelming

Crushing sense of being overpowered .

“The layers of noise from all the alarms and instruments made the room feel overwhelming .”

“The overwhelming hospital room was bursting with activity.”

Because overwhelming suggests a loss of power or control, describe the room as overwhelming to show the reader your character is struggling to come to terms with brought them to the hospital in the first place.

How to Write Hospital Scenes (21 Best Tips + Examples)

Hospitals are places where life’s most poignant moments unfold, from the joy of birth to the sorrow of passing away.

As such, hospital scenes show up in a lot of stories.

Here is how to write hospital scenes:

Write hospital scenes by understanding the medical hierarchy, capturing authentic ambiance, using medical jargon sparingly, and emphasizing emotional dynamics. Consider the patient’s journey, relationships, and triumphs. Every element should enhance the realism and emotional depth of the scene.

In this guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know about how to write hospital scenes.

1. Understand the Hospital Hierarchy

Table of Contents

Understanding the hospital hierarchy is crucial.

Hospitals aren’t just about doctors and nurses. They’re made up of an intricate web of professionals working cohesively.

Knowing the roles of various healthcare professionals adds depth to your scene.

Whether it’s an interaction between a resident and an attending physician, or between a nurse and a technician, understanding these dynamics can create tension or camaraderie in your writing.

As Dr. Smith entered the room, she nodded at the nurse. “How’s our patient today, Jane?” Jane, an experienced ICU nurse, responded, “Stable, but his oxygen levels dipped overnight. The respiratory therapist worked on it, and they’re improving now.”

2. Capture the Hospital Ambiance

The atmosphere in a hospital is unique.

The constant beep of monitors, the murmurs of visitors, and the distant announcements over the intercom form a backdrop to your scene.

A vivid atmosphere sets the mood.

Is it a quiet night or a bustling day? The ambiance can reflect the emotional tone of the scene.

The dimly lit hallway echoed with soft footsteps, punctuated by the occasional beep from a room further down. Somewhere, a baby cried, and a nurse’s voice softly tried to soothe.

3. Use Medical Jargon Judiciously

While it’s tempting to throw in medical terms to sound authentic, overusing them or using them incorrectly can confuse readers.

Medical jargon, when used correctly, lends authenticity.

But it’s crucial to ensure the reader can understand the context.

“We’ve started him on a course of IV antibiotics. His white blood cell count was high, indicating an infection.”

4. Show the Emotional Toll

Hospitals are places of healing, but they’re also where people face mortality, pain, and fear.

Capturing the emotional landscape provides depth to your characters and connects readers to the story.

Remember, not everyone in a hospital is a patient; families, visitors, and even healthcare professionals have their emotional journeys.

Nurse Daniels looked out the window for a moment, taking a deep breath to compose herself after the last patient’s passing. The weight of the day heavy on her shoulders.

5. Research Common Procedures

Researching common medical procedures can help you craft realistic scenarios.

Readers, especially those with some medical background, appreciate accuracy.

Getting the details right can boost your story’s credibility.

Sarah watched as the nurse prepared the IV line, ensuring all air bubbles were out before inserting it into her arm.

6. Distinguish between Different Wards

Not all hospital areas are the same.

An ICU differs from a maternity ward or a general patient room.

Distinguishing between different wards can help set the scene, tone, and pace. For instance, an emergency room scene will have a different urgency than a scene in a recovery ward.

The ER was a flurry of activity, with paramedics rushing in and doctors shouting orders. Two floors up, in the recovery ward, it was a different world. Here, the pace was slower, with patients resting and nurses moving quietly between rooms.

7. Remember the Role of Technology

Modern hospitals are technologically advanced.

From MRI machines to portable ECGs, technology is everywhere.

Incorporating technology not only adds realism but also can create tension or relief, depending on the situation.

The room was tense as everyone stared at the ultrasound monitor. A moment later, the unmistakable sound of a heartbeat filled the small space, bringing tears of relief to Maria’s eyes.

8. Understand the Patient Experience

Every individual’s journey through a hospital varies based on the reason for their visit, their past experiences, and their personal anxieties.

The emotional and physical state of a patient is central to their perspective.

They may be overwhelmed, scared, hopeful, or even indifferent.

A writer should consider these emotions when crafting their characters’ responses to treatments, their interactions with medical staff, and even their internal monologue.

Lying in the sterile room, Mark felt exposed. The cold sheets beneath him, the foreign sounds — everything made him uneasy.

9. Highlight Interpersonal Dynamics

Relationships and interactions are the lifeblood of any setting, and hospitals are no exception.

The professional and personal dynamics between staff members can add layers of complexity to a scene.

Perhaps two doctors have conflicting treatment philosophies, or a nurse and a patient share a poignant moment.

These relationships can be sources of both conflict and collaboration, driving the narrative forward and allowing for multifaceted character exploration.

Dr. Patel and Nurse Ramirez had a renowned partnership. Where one was, the other wasn’t far behind, their synchronized movements a testament to years of collaboration.

10. Address Ethical Dilemmas

The hospital setting is fertile ground for moral quandaries, given the life and death decisions made daily.

Ethical dilemmas force characters to confront their values and priorities.

This can range from debates about end-of-life care to the potential ramifications of experimental treatments.

Exploring these tough decisions can provide depth to your narrative and give characters opportunities to evolve and grow.

Faced with the choice of continuing treatment or opting for palliative care, Jenna’s family was divided, each member grappling with their convictions.

11. Don’t Forget the Waiting Rooms

While patient rooms are pivotal, waiting areas serve as intersections of myriad emotions and interactions.

Waiting rooms often encapsulate the anticipation, anxiety, and hope of families and friends.

They can serve as places of bonding between strangers, reflections on the past, or moments of unexpected news.

By delving into the microcosm of the waiting room, writers can unveil diverse human experiences and emotions.

As Sarah waited, she struck up a conversation with an older man, their shared worries forging an unexpected bond.

12. Include Flashbacks or Memories

Hospital environments, laden with emotions, can act as catalysts for characters to relive past experiences.

These flashbacks can be directly related to the current medical situation or completely tangential, offering insights into a character’s past traumas, joys, or significant life events.

Leveraging these memories can create juxtapositions with the present and highlight character growth or unresolved issues.

As the anesthesiologist spoke, Clara’s mind drifted back to her childhood accident — the reason for her phobia of hospitals.

13. Use Senses Beyond Sight

A multisensory approach makes a scene more immersive and vivid for the reader.

Hospitals are a cacophony of sounds, smells, and textures.

From the sterile scent of disinfectant to the soft hum of machines or the rough texture of a bandage, engaging multiple senses offers a comprehensive and engrossing portrayal of the environment, drawing readers into the scene.

The antiseptic smell was overpowering, the occasional distant cough and soft hum of machinery serving as a constant reminder of where she was.

14. Introduce Unexpected Humor

In the face of adversity, humor can act as a relief valve, revealing character resilience.

Moments of levity in tense or somber situations can humanize characters.

It can show their coping mechanisms or their attempts to uplift others.

This contrast can make the gravity of a situation even more poignant while offering readers moments of reprieve.

“You’d think after all these years, they’d find a gown that actually closes in the back,” mused John, earning a chuckle from the nurse.

15. Respect Cultural and Religious Sensitivities

Acknowledging the diverse tapestry of patient backgrounds enhances realism and inclusivity.

Medical decisions, comfort levels with treatments, and interactions with hospital staff can all be influenced by cultural or religious beliefs.

It’s important for writers to enrich their narrative with representation and respect for diverse perspectives.

Mrs. Khan hesitated, her cultural beliefs about modesty making her wary of the male doctor. Recognizing this, Nurse Garcia gently stepped in to mediate.

16. Show Fatigue and Stress among Healthcare Workers

Behind the clinical professionalism, healthcare workers grapple with the emotional and physical demands of their roles.

These professionals often bear witness to intense human experiences, from birth to death and everything in between.

Chronicling their exhaustion, moments of doubt, or instances of resilience can offer a balanced view of the hospital ecosystem.

Not only that but it can also emphasize the human element behind the medical expertise.

After a 16-hour shift, Dr. Lee’s steps were heavy. She paused for a moment, rubbing her temples, before moving on to the next patient.

17. Address the Financial Aspects

The economics of healthcare can be a significant concern for patients and families.

Financial worries can compound the stress of a medical situation.

Addressing these concerns — be it through the lens of insurance battles, out-of-pocket costs, or the broader healthcare debate — can root your story in real-world challenges, making it more relatable and timely.

The relief that her mother was recovering was overshadowed by the mounting medical bills that Amy now faced, a dilemma she hadn’t anticipated.

18. Highlight Moments of Triumph

Despite the challenges, hospitals are also spaces of recovery, healing, and miracles.

Emphasizing moments of success or relief, whether they’re medical breakthroughs or personal victories like a patient taking their first step post-surgery, can infuse your narrative with hope and inspiration.

These moments underscore the resilience of the human spirit and the dedication of medical professionals.

Against all odds, Mr. Rodriguez took his first steps after the accident, the entire ward cheering him on.

19. Include External Influences

The world outside doesn’t stop when one enters a hospital. External events can influence the internal dynamics of the setting.

By weaving in external influences, you can showcase the adaptability of the hospital environment and its staff.

Whether it’s a natural disaster leading to an influx of patients or a city-wide event affecting hospital operations, these external elements can add layers of complexity to your narrative.

As the city marathon was underway, the ER braced for a busy day, anticipating the influx of dehydration cases and potential injuries.

20. Detail Personal Keepsakes

Personal items offer glimpses into a patient’s world outside the hospital, grounding them in reality.

These keepsakes can act as symbols of hope, reminders of loved ones, or touchstones of normalcy in an otherwise clinical environment.

Detail these items and their significance to build deeper emotional connections between characters and readers.

Next to Mrs. Everett’s bed stood a framed photo of a young couple on their wedding day, a testament to a love that had weathered many storms.

21. Remember the Power of Touch

In an environment often dominated by machines and medical instruments, human touch stands out.

Touch, whether comforting or clinical, can convey a multitude of emotions.

A reassuring hand on a shoulder, a clinical examination, or a desperate grasp during a moment of fear can be powerful narrative tools, emphasizing human connection and vulnerability.

As the news settled in, James reached out, gently squeezing his sister’s hand. In that simple gesture, he conveyed the strength and support she desperately needed.

Check out this video about how NOT to write hospital scenes (Unless you’re going for pure comedy):

30 Words to Describe Hospital Scenes

The words you choose for your hospital scenes will alter the mood, tone, and entire reader experience.

Here are 30 words you can use to write hospital scenes:

- Fluorescent

- Reverberating

- Crisp (as in uniforms)

- Intermittent

- Cold (as in touch)

- Harsh (as in lights)

- Labored (as in breathing)

30 Phrases to Write Hospital Scenes

Try these phrases when writing your hospital scenes.

Not all of the phrases will work for your story (or any story) but, hopefully, they will help you craft your own sentences.

- “A symphony of monitors beeped in rhythm.”

- “Whispers filled the corridor, punctuated by distant footsteps.”

- “The scent of disinfectant was almost overpowering.”

- “Nurses moved with practiced efficiency.”

- “The weight of anticipation hung in the air.”

- “A curtain rustled softly in the next bed.”

- “Lights overhead cast stark shadows on the floor.”

- “Intercom announcements broke the tense silence.”

- “Machines whirred and clicked in the background.”

- “Soft murmurs of comfort echoed.”

- “Trolleys clattered past at regular intervals.”

- “Gauzy curtains diffused the morning light.”

- “A stifled sob broke the sterile calm.”

- “The rhythmic pulse of the heart monitor filled the void.”

- “The chill of the tiles was evident even through socks.”

- “Hushed conversations ceased at the doctor’s arrival.”

- “Labored breathing was the room’s only soundtrack.”

- “A clipboard clattered to the ground, shattering the quiet.”

- “The distant hum of an MRI machine grew louder.”

- “The atmosphere was thick with a mix of hope and despair.”

- “Patients lay in rows, separated by thin partitions.”

- “The waiting area was a mosaic of emotions.”

- “Doctors consulted charts with furrowed brows.”

- “IV drips punctuated the silence with their steady rhythm.”

- “A sudden rush of activity signaled an emergency.”

- “Whirring fans attempted to combat the stifling heat.”

- “Shadows played on the wall as the day waned.”

- “The fluorescent lights buzzed overhead, unceasing.”

- “A lone wheelchair sat abandoned in the hall.”

- “Gentle reassurances were whispered bedside.”

3 Full Examples of Writing Hospital Scenes

Here are three complete examples of how to write hospital scenes in different genres.

The hallway of St. Mercy’s was dimly lit, echoing with the soft murmurs of the night shift nurses.

Elizabeth walked slowly, her heels clicking on the tiles, each step feeling like an eternity as she approached room 309. The scent of antiseptics was faint but ever-present, reminding her of the weight of the place. As she pushed open the door, the rhythmic beeping of the heart monitor greeted her, and in the dim light, she saw her father, pale but stable.

Tears welled up, not out of sorrow, but of gratitude.

2. Mystery/Thriller

Detective Rowe entered the ICU, the atmosphere thick with tension.

The overhead lights cast a harsh glow on the room where the city’s mayor lay unconscious. A nurse, her uniform crisp and white, glanced up, her eyes betraying a mix of curiosity and wariness. Rowe noted the machines surrounding the bed — their mechanical hums and beeps creating a symphony of medical surveillance.

He needed answers, and everything about this sterile room was a potential clue.

3. Sci-fi/Fantasy

In the celestial infirmary of Aeloria, walls shimmered with iridescent lights, and the air pulsed with ancient magic.

Elara, the moon sorceress, lay on a floating bed, her aura flickering like a candle nearing its end.

Surrounding her were crystal devices, pulsating and humming in an ethereal dance. Lyric, her apprentice, whispered an incantation, her voice intertwining with the mystical ambiance, hoping to revive her mentor with a blend of ancient spells and cosmic medicine.

Final Thoughts: How to Write Hospital Scenes

Crafting a compelling hospital scene is an intricate dance of authenticity, emotion, and meticulous detail.

For more insights on writing stories, please check out the other articles on my website.

Related Posts:

- How to Write Flashback Scenes (21 Best Tips + Examples)

- How to Foreshadow Death in Writing (21 Clever Ways)

- How to Write Fast-Paced Scenes: 21 Tips to Keep Readers Glued

- How to Describe Crying in Writing (21 Best Tips + Examples)

SLAP HAPPY LARRY

Writing activity: describe medical rooms and hospitals.

Medical rooms and hospitals are safe, infantalising, dangerous, creepy, life-saving, traumatising places, and I offer them here as examples of what Foucault called ‘ heterotopia ‘.

The hospital’s ambiguous relationship to everyday social space has long been a central theme of hospital ethnography. Often, hospitals are presented either as isolated “islands’ defined by biomedical regulation of space (and time) or as continuations and reflections of everyday social space that are very much a part of the “mainland.’ This polarization of the debate overlooks hospitals’ paradoxical capacity to be simultaneously bounded and permeable , both sites of social control and spaces where alternative and transgressive social orders emerge and are contested. We suggest that Foucault’s concept of heterotopia usefully captures the complex relationships between order and disorder, stability and instability that define the hospital as a modernist institution of knowledge, governance, and improvement . Heterotopia Studies

Hospitals (like airports) elicit the full range of human emotion and are symbolically useful arenas for storytellers. Who better than writers to describe what it feels like to be inside a hospital?

I followed [the psychiatrist] down a depressing hallway into a tiny windowless office that might have housed an accountant. In fact it reminded me a bit of Myron Axel’s closet, filled with piles of paper waiting to be filed, week-old cups of coffee turned into science experiments, and a litter of broken umbrellas nesting beneath the desk. I must have looked as surprised as I felt when I entered her office, for Rowena Adler looked at the utilitarian clutter about her and said, “I’m sorry about this mess. I’m so used to it. I forget how it looks.” Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You by Peter Cameron

The author may have enjoyed writing that description because at James Sveck’s next appointment they are in a different room.

Dr Adler’s downtown office was a pleasanter place than her space at the Medical Center, but it wasn’t the sun-filled haven I had imagined. It was a rather small dark office in a suite of what I assumed were several small dark offices on the ground floor of an old apartment building on Tenth Street. In addition to her desk and chair there was a divan, another chair, a ficus tree, and some folkloric-looking weavings on the wall. And a bookcase of dreary books. I could tell they were all nonfiction because they all had titles divided by colons: Blah Blah Blah: The Blah Blah Blah of Blah Blah Blah . There was one window that probably faced an airshaft because the rattan shade was lowered in a way that suggested it was never raised. The walls were painted a pale yellow, in an obvious (but unsuccessful) attempt to “brighten up” the room.

The description of James’ psychiatrist’s rooms is broken up, judiciously, and fits around the action. James’ reaction to the rooms reflects how he feels about life at this juncture: He expected better. He expected different; instead he gets this underwhelming life.

I looked around her office. I know it sounds terrible, but I was discouraged by the ordinariness, the expectedness, of it. It was as if there was a catalog for therapists to order a complete office from: furniture, carpet, wall hangings, even the ficus tree seemed depressingly generic. Like one of those little paper pellets you put in water that puffs up and turns into a lotus blossom. This was like a puffed-up shrink’s office.

In a book of essays, Tim Kreider’s description of hospitals is one of the best I’ve encountered:

Hospitals are like the landscapes in recurring dreams: forgotten as though they’d never existed in the interims between visits, but instantly familiar once you return. As if they’ve been there all along, waiting for you while you’ve been away. The endlessly branching corridors sand circular nurses’ stations all look identical, like some infinite labyrinth in a Borges story. It takes a day or two to memorize the route from the lobby to your room. The innocuous landscape paintings that seem to have been specifically commissioned to leave no impression on the human brain are perversely seared into your long-term memory. You pass doorways through which you can occasionally see a bunch of Mylar balloons or a pair of pale, withered legs. Hospital beds are now just as science fiction predicted, with the patient’s vital signs digitally displayed overhead. Nurses no longer wear the white hose and red-cross caps of cartoons and pornography, but scrubs printed with patterns so relentlessly cheerful—hearts, teddy bears, suns and flowers and peace signs—they seem symptomatic of some Pollyannaish denial. The smell of hospitals is like small talk at a funeral—you know its function is to cover up something else. There’s a grim camaraderie in the hall and elevators. You don’t have to ask anybody how they’re doing. The fact that they’re there at all means the answer is: Could be better. I notice that no one who works in a hospital, whose responsibilities are matters of life and death, ever seems hurried or frantic, in contrast to all the freelance cartoonists and podcasters I know. Time moves differently in hospitals—both slower and faster. The minutes stand still, but the hours evaporate. The day is long and structureless, measured only by the taking of vital signs, the changing of IV bags, medication schedules, occasional tests, mealtimes, trips to the bathroom, walks in the corridor. Once a day an actual doctor appears for about four minutes, and what she says during this time can either leave you and your family in terrified confusion or so reassured and grateful that you want to write her a thank-you note she’ll have framed. You cadge six-ounce cans of ginger ale from the nurses’ station. You no longer need to look at the menu in the diner across the street. You substitute meat loaf for bacon with your eggs. Why not? Breakfast and lunch are diurnal conventions that no longer apply to you. Sometimes you run errands back home for a cell phone or extra clothes. Eventually you look at your watch and realize visiting hours are almost over, and feel relieved, and then guilty. Tim Kreider, “An Insult To The Brain”, We Learn Nothing

It’s a fact known throughout the universes that no matter how carefully the colours are chosen, institutional décor ends up either vomit green, unmentionable brown, nicotene yellow or surgical appliance pink. Terry Pratchett, Equal Rites

They are now the only two people in the upstairs waiting room of the dental clinic. The seats are a pale mint-green colour. Marianne leafs through an issue of NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and explores her mouth with the tip of her tongue. Connell looks at the magazine cover, a photograph of a monkey with huge eyes. from “At The Clinic” by Sally Rooney

Every time I see a hospital in a horror movie or whatever, sometimes even an actual prison, I compare it to the one I went to and it always comes out looking worse. They are not relaxing places. They can leave you worse than you came in. Especially because the world outside, doesn’t actually stop while you are there? You’re usually there due to a crisis. Something unexpected. Did you take vacation pay before you started? Probably not, hey? Provided that you get that sort of thing at all. If you’re on welfare, you’re still have to fight for an exemption. Good luck if you can’t do that because you’re literally insane. You’ll still need to pay the rent and all your bills somehow in the background too. Oh, you got kicked out? That’s a shame. Here’s a pamphlet to a homeless shelter. Have a lovely trip. My stay did turn out a lot better than that, but it’s literally only because I had someone constantly advocating for me on the outside. Most people in psych wards don’t get that. And that’s not even touching on how nobody will listen to you in there, but everybody will assume all sorts of things about you. You’ll be open to both sexual and physical assault. Both happened to me on a number of occasions. I was blamed for everything, of course. You don’t even get uninterrupted sleep, do you know that? Nurses come and shine a torch in your face every fucking hour for a wellness check, or whatever. Which feels pretty shitty if you’re going through a paranoid psychosis. Anyway. I’d really like to see more empathy and awareness of the reality of all these sorts of places. They are horrible. They haven’t changed a lot since they were called asylums. They still use solitary confinement too, did you know that? Awful things. Mx Maddison Stoff @TheDescenters Sep 8, 2022

FURTHER READING

What’s It Like To Work In A Psych Hospital? is a podcast from Psych Central with someone who explains how psychiatric hospitals are traumatising for everyone in and around them, not just for the patients.

The Architecture of Madness

Elaborately conceived, grandly constructed insane asylums—ranging in appearance from classical temples to Gothic castles—were once a common sight looming on the outskirts of American towns and cities. Many of these buildings were razed long ago, and those that remain stand as grim reminders of an often cruel system. For much of the nineteenth century, however, these asylums epitomized the widely held belief among doctors and social reformers that insanity was a curable disease and that environment—architecture in particular—was the most effective means of treatment. In The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States (U Minnesota Press, 2007), Carla Yanni tells a compelling story of therapeutic design, from America’s earliest purpose—built institutions for the insane to the asylum construction frenzy in the second half of the century. At the center of Yanni’s inquiry is Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, a Pennsylvania-born Quaker, who in the 1840s devised a novel way to house the mentally diseased that emphasized segregation by severity of illness, ease of treatment and surveillance, and ventilation. After the Civil War, American architects designed Kirkbride-plan hospitals across the country. Before the end of the century, interest in the Kirkbride plan had begun to decline. Many of the asylums had deteriorated into human warehouses, strengthening arguments against the monolithic structures advocated by Kirkbride. At the same time, the medical profession began embracing a more neurological approach to mental disease that considered architecture as largely irrelevant to its treatment. Generously illustrated, The Architecture of Madness is a fresh and original look at the American medical establishment’s century-long preoccupation with therapeutic architecture as a way to cure social ills. interview at New Books Network

The Architecture of Good Behavior: Psychology and Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America

Inspired by the rise of environmental psychology and increasing support for behavioral research after the Second World War, new initiatives at the federal, state, and local levels looked to influence the human psyche through form, or elicit desired behaviors with environmental incentives, implementing what Joy Knoblauch calls “psychological functionalism.” Recruited by federal construction and research programs for institutional reform and expansion—which included hospitals, mental health centers, prisons, and public housing—architects theorized new ways to control behavior and make it more functional by exercising soft power, or power through persuasion, with their designs. In the 1960s –1970s era of anti-institutional sentiment, they hoped to offer an enlightened, palatable, more humane solution to larger social problems related to health, mental health, justice, and security of the population by applying psychological expertise to institutional design. In turn, Knoblauch argues, architects gained new roles as researchers, organizers, and writers while theories of confinement, territory, and surveillance proliferated. The Architecture of Good Behavior: Psychology and Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America (University of Pittsburgh Press) explores psychological functionalism as a political tool and the architectural projects funded by a postwar nation in its efforts to govern, exert control over, and ultimately pacify its patients, prisoners, and residents. interview at New Books Network

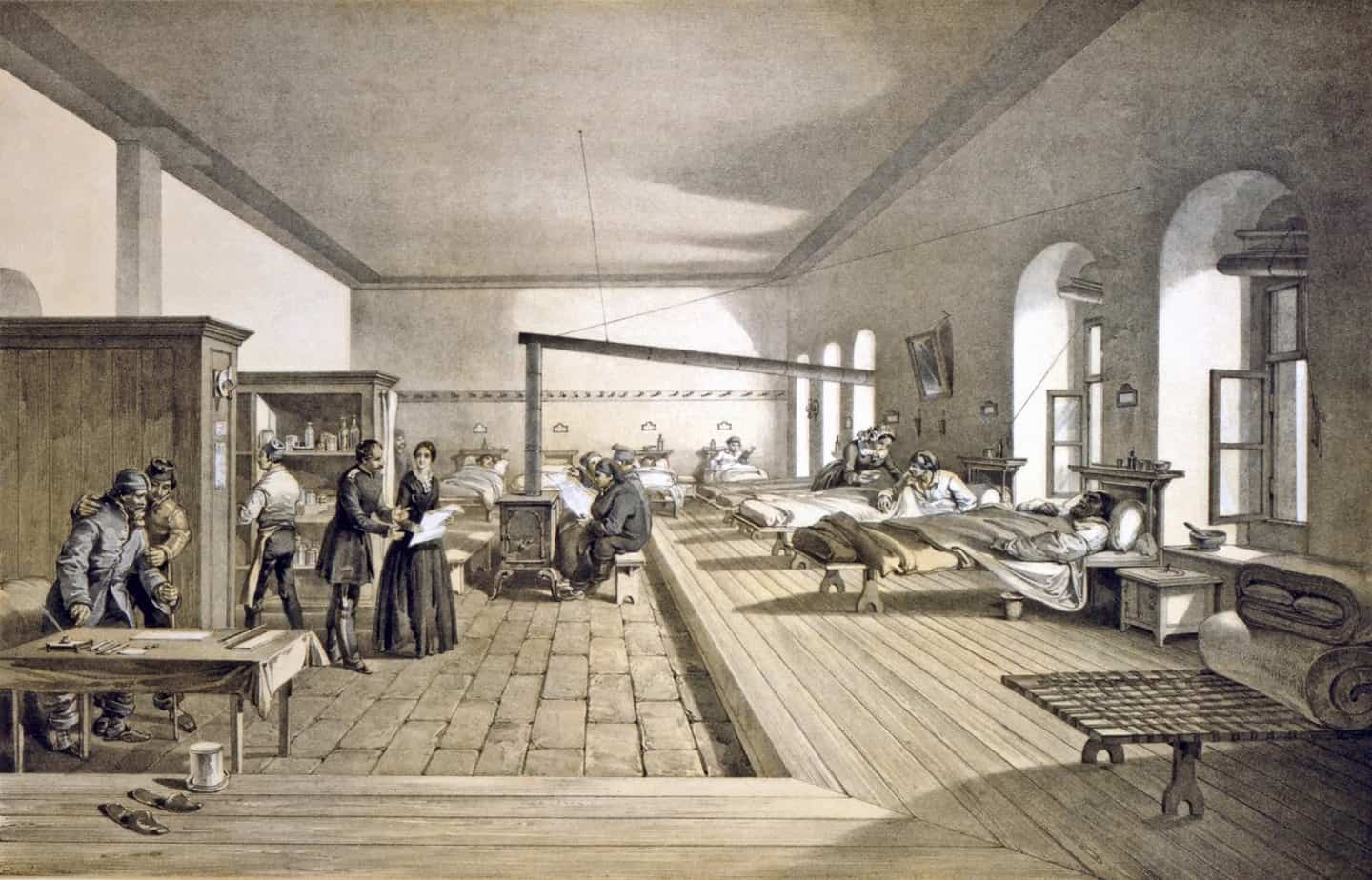

Header painting: William Simpson – One of the wards of the hospital at Scutari 1856

LATEST AUDIOBOOK (short story for children)

Write that Scene

May your writing spirit live on forever

How to Write a Hospital Scene

SHARE THIS SITE WITH THE WORLD!

In a rush? Skip to part three…..

- There are two different types of hospitals. Mental Hospital and the regular hospital we’ve all been in. For this scene in particular I will be focusing on the latter.

» A. Explain to your audience why the character(s) is in the hospital and whether or not it’s for them or a friend/family member.

I. What does the character bring and how long do they wait? Is it in the ER which is for emergencies or is in the regular waiting room. Please note: if someone was shot or given birth or the like, this person would get priority treatment in the ER.

II. Kids under the age of 18 would likely be on a pediatric ward. There are exceptions, for instance if the injuries sustained were severe enough to be in the ICU (Intensive Care Unit) or possibly the step down unit. If they had to be revived but had no other injuries, they probably wouldn’t even be admitted to the hospital.

III. What happens in the waiting room, if anything? Are confessions made, friends met, someone arrested, or nothing because the person goes straight to a room? Any complaints made out of frustration or anguish?

IV. How is (whatever they are experiencing) affecting them? Were the character(s) on a adrenaline high after breaking their arm from falling off a motorcycle but now is feeling the pain? If so, have them scream in pain, cry, hit something, bit their lip, breath in and out hard. Let’s say they have a disease, then maybe they are praying, holding the hand of their loved one tight, closing their eyes, rocking back and forth in their chair, etc. If they are waiting for someone then maybe they do the same things as mentioned above.

Example 1: (Coming Soon).

» B. What do the doctors/ surgeons have to say? Anything good or all bad news? .

Note: The following can occur-

- The doctor would say everything is okay and nothing needs to be done. Patient accepts and walks out. Maybe something minor is done like a cast for a sprain or a scan to check if any bones are broken. Even then, the character is fine and walks out free.

- The doctor tells the patient everything is fine but the patient doesn’t believe them. They demand a second opinion or to be rechecked.

- Doctor finds something wrong with the patient and character needs to stay in order to be diagnosed. Or leaves out the hospital with pills, in a wheel chair, or surgery schedule for something major (if that has not already occurred in the ER).

I. If the doctor finds nothing wrong with the character and the character agrees you can add the following in order to progress your story along: maybe a family member demands a recheck; or another doctor comes in with bad news of their own and apologizes that the other doctor almost missed the problem; a hug between the doctor and patient is given; or another problem is diagnosed that is not related to what your character came in to the hospital for.

II. If the character doesn’t believe the doctor; you can add the following: character becomes uncontrollable and becomes an endangerment to everyone around; therefore they are taken to a mental hospital; character continues to argue with doctor and if character is educated discuss why the doctor is wrong; character goes through another checkup to make sure they are free of anything. Maybe the results come back with something wrong.

NOTE: To be admitted into psychiatric care one has to meet a certain criteria. So the character could then be admitted after being in the hospital and after being assessed by a professional.

III. If something is found, then doctors may do even more checks with various devices such as MRI, ultrasound, EMG (for nerve tests), and so on. Be sure to identify the appropriate tests your character will take depending on their circumstance. Someone coming in for a cold will not need any scans unless the cold has lasted a month or several months. Maybe the patient has more symptoms than a cold and will get a test done. Don’t forget about blood tests.

Now, if something is found the doctor should tell the character how they will treat them and what are the next steps. Cancer has chemo therapy. Cysts and odd lumps has surgery and aspiration. Colds have medicine and a disease usually has pills. There is more to it than that, this is where you would have to do a bit more research.

Use this as a chance to bring multiple generations together. When a loved one is in crisis, usually their whole family unites, bringing a mix of personalities into the same place at the same time. The scene would flow naturally from there, based on the characters’ relationships to each other and primary motivations.

(Coming Soon).

» C.Emotions Cannot Be Ignored! !

I. It doesn’t matter what the doctor told your character, good or bad, what is your character feeling? As if a massive truck has been lifted from their shoulders when they found out their disease is curable.

II. If bad, what do they do, how are they feeling? Does the world stop, do they faint, do they become a statue. Now is the time to give you audience background about why your character took the news the way the did. Example:

III. What is promised to the character from the doctor? Usually a promise is made like, you will get better or it will not affect your work. Little promises that can mean a lot. So, have the doctor promise your character something that is important to your story. If your character is an athlete your doctor may promise him/her they will be able to play the sport again in a few short months. If your character is a singer and has laryngitis, the doctor may promise that even though their voice sounds like a pen scratching chalkboard now, she/her will be able to sing again. This promise is important because it gives the reader a since of the emotional aspect but also the technical aspect. Meaning, there is a cure for their problem. However, if the problem has no treatment then the doctor may promise them this: I will be with you along the way…. You still have a few short months to live… there is a cure being found in east Asia maybe in a few months they will allow me to use it on you.

Example 3: (Coming Soon).

- Get into that atmosphere. Let it play a key roll in this scene. These examples will be primarily for the ER but can be used for others.

» A. Describe the room…

- Low light on at all times, and there are cords hanging down for the nurses call button and the IV solutions.

- An electronic machine sitting on a cart with odd wires leading from it,a privacy curtain hanging from a track on the ceiling.

- The bedside table has several get well cards and a bouquet of flowers.

- There is an aqua colored water glass with a bent straw in it, a half eaten tray of food with the big metal cover that was on the plate, and a telephone that doesn’t work.

- Door is propped open, and nurses and orderlies walk by, their sensible shoes squeaking on the pristine tiles.

- A TV hangs in the corner, tuned to the Reverend Bob H. Wells- who thinks you should write him a large check for a blessing- because the remote control is lost, and the TV is too high for the nurses to reach.

- There are wires glued to the character’s chest and coming up through the neck of their hospital gown…the most embarrassing garment invented that has no back and lets every human know what the underwear look like.

- The window has a mini blind on it, and a view of the roof of an adjoining building.

- For those of you in a rush, here is some bits and pieces of What a Hospital Scene Will Contain:

» A. Entering the hospital:

- Nurses trying to be helpful, directing you to where you would like to go.

- The floor is shining clean, long corridors.

- Signs in green saying EXIT.

- Rooms with numbers on the doors.

- Some doors are open and you can see the patient according to their situation, could be sleeping, visiting with a

- relative, others with oxygen tubs applied at their noses.

- At the Nurses Desk lots of laugh although the rule is of “Shhh”.

- Nurses no longer wearing white starched uniforms neither white shoes or stocking go and come, many with dirty

- tennis shoes, and instead of the uniform wear just regular half shirts .

- The rooms could be private ( one patient in it) others could be semi-private ( two patients in one room)

- Also it can be a Ward, meaning a long row of beds for a Charity Ward, this one is very sad to see.

- If the doctors have the rounds they stop to check the chart of each patient.

- When the person is bleeding or in with a heart attack they are taking immediately to the attention of the Physician on duty.

- Describe the journey back home. Whether after a surgery or a general checkup.

» A. Leaving the doctors room, how does your character act?

I. Is their head hanging low from shame and sadness, head up high in pride and happiness? Hands clapped together for peace or in pockets for failure, remorse? Silent? Rejoicing to the high heavens?

II. Do they go home alone and if so where do they stop on the way? Are they so grateful for life that they say sorry to their mortal enemy. Do they go to a church to repent? Do they go home to do research on their problem? Do they call a friend? III. Maybe you can have the character speak to someone on the way out. Tell that person everything would be okay, or an update about their visit, or something to leave an imprint. Especially if a truck has been lifted off their shoulder. IV. Lastly, how is the news broken or given to their loved ones? In person? At the hospital where everyone gives a big hug of congratulations or sadness? Show who is important to your character and how they share the news with them. It will show a more-in-depth look at your character. The best way to understand anyone is when they are going through a crises. Show your audience who your character truly is and how they handle their news. Example 7: (No Example Added- but you can add one for your scene).

** !You might have to scroll down the textbox with your mouse!

coming soon

Chat Room [wise-chat]

Related posts:

6 thoughts on “ How to Write a Hospital Scene ”

I need this one to complete my book PLZ I need a outline

I will try to finish it by the end of this month, Amayah.

Hi! I can’t even begin to explain how AMAZINGLY HELPFUL this site is. I can use so many of these little pages; kidnaping for about 3-5 different stories of mine (also the starving one), the hospital one for the aftermath of the rescue. The “falling in love” one for young teenagers, and then the “first date” for two people who finally admit their feelings for each other.

I can use the funeral one for at least 2 stories. The dying, car crash, saying goodbye, flying, wedding, I mean this is like the best early Christmas present I’ve ever gotten. It’s all the help I need for my 12+ story in one place! I can’t believe I’ve only just now found this site, and I will DEFINITELY link it to my profile so my fellow readers can come and get help.

Thank you, thank you, thank you so much! Who’s ever idea this one to make this webpage is a genius! 🙂

Glad to be of help, Reagan! Happy Holidays 🙂

MMMM. That was nice. But it didn’t let me combine the test. Is okay tho, found this Super helpful!!! ten out of ten, will definitely use this again.

Very helpful. What about an example of paramedics bringing into the ER a seriously injured victim of, say, a car crash, where they have suffered multiple fractures and perhaps have some internal bleeding. What would be some of the things the paramedic would report to the ER team? Who would be present and what would they be doing and saying from the moment the paramedics roll the gurney into the ER, the handover to ER staff, and perhaps even the initial few minutes of care in the ER?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

Recent comments.

Copyright © 2024 Write that Scene

Design by ThemesDNA.com

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

WRITERS HELPING WRITERS®

Helping writers become bestselling authors

Setting Description: Emergency Waiting Room

June 5, 2010 by ANGELA ACKERMAN

Automatic sliding doors, beat-up chairs (filled with people who have: broken limbs, cuts, red noses, bruising, scrapes, holding garbage bins to throw up in, are wearing surgical masks, are crying, have been beaten, are holding onto the person next to them for support, reading magazines, books, clutching at purses or holding tight to jackets slung over an arm, leaning back in their chair asleep), overflowing garbage bins, half finished coffee containers

Whispering, crying, uneven or distressed breathing, the sound of someone throwing up, moaning, groaning, whimpering, pleasing, praying, newspapers rattling, arguing, magazine pages flipping, the papery slide of a book page being turned, the pop and fizz of a pop can being opened, static-y police & security radios

Antiseptic, cleaning products, hand sanitizer, vomit, BO, sweat, booze breath, coffee, taco chips, perfume, hair products, cough drops, air conditioned & filtered air

Coffee in a container, pop, juice and water from a container, snack foods from a vending machine, mints, gum, nicorette. Most people try hard not to eat in the waiting room because of the risk of exposure to airborne and surface contaminants.

Thin padded or plastic seats offering little comfort or room, metal arm rails digging into forearms, making oneself ‘small’ and holding self straight to avoid touching those to either side, twisting the admittance band on wrist, rolling shoulders, crossing and recrossing legs, twisting a wedding band, rubbing eyes, pinching bridge of the nose, rubbing arms and shaking self in an attempt to stay awake

Helpful hints:

–The words you choose can convey atmosphere and mood.

I stared down at my hands, twisting and knotting them as if doing so would hold back the turmoil inside me. Despair roamed the room, expelled on the breath of worriers like me and those doing their best to bite down on the pain that brought them here.

–Similes and metaphors create strong imagery when used sparingly.

Example 1: (Simile)

After the symphony of coughing, hacking and wheezing that greeted Becky in the ER waiting room, she found the closest antibacterial hand dispenser and starting working it like a gambling addict hitting up a VLT machine.

Think beyond what a character sees, and provide a sensory feast for readers!

Setting is much more than just a backdrop, which is why choosing the right one and describing it well is so important. To help with this, we have expanded and integrated this thesaurus into our online library at One Stop For Writers . Each entry has been enhanced to include possible sources of conflict , people commonly found in these locales , and setting-specific notes and tips , and the collection itself has been augmented to include a whopping 230 entries—all of which have been cross-referenced with our other thesauruses for easy searchability. So if you’re interested in seeing a free sample of this powerful Setting Thesaurus, head on over and register at One Stop.

On the other hand, if you prefer your references in book form, we’ve got you covered, too. The Urban Setting Thesaurus and The Rural Setting Thesaurus are available for purchase in digital and print copies. In addition to the entries, each book contains instructional front matter to help you maximize your settings. With advice on topics like making your setting do double duty and using figurative language to bring them to life, these books offer ample information to help you maximize your settings and write them effectively.

Angela is a writing coach, international speaker, and bestselling author who loves to travel, teach, empower writers, and pay-it-forward. She also is a founder of One Stop For Writers , a portal to powerful, innovative tools to help writers elevate their storytelling.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Reader Interactions

June 7, 2010 at 10:50 pm

Great job, Angela!

Having spent more time with my late husband in the ER than I care to remember, I’d add:

Triage area Casting room (for broken bones) X-Rays/CAT Scan IV’s Blood pressure cuffs Isolation room for those with lowered immune system (there’s a name for it, but I can’t recall what it is). Heart monitors Admissions clerks taking information with computers on portable carts.

I could probably come up with more, but it’s late. 🙂

Blessings, Susan

June 7, 2010 at 6:31 pm

Since I’ve spent too much time in too many emergency rooms, your post struck a true chord with me.

It seems you’re fond of zombies. I found a new author site that details a zombie I don’t think I ever before read about : http://fictitiousflashes.blogspot.com/

Not mine. That would be too tacky. But blog just starting out. Lena shows great promise, and I thought it might be nice for all of us to pop in and surprise her with a warm, friendly hello. Roland

June 7, 2010 at 2:19 pm

The whiff of hand sanitizer hangs heavy over this post, Angela. In fact, I feel a cough coming on. I hope I’m not catching something. Or worse, getting MRSA!!!! AHHHH!!!

Hope your hubby is feeling better and life is getting back on an even keel.

June 7, 2010 at 1:31 pm

Great post! I’ve recently learned to do this…to close my eyes and take each sense at a time. To actually put myself there in the moment and write it. Not on the first draft, necessarily, but certainly on the revision. I’ve been there in the ER, and you put me right there again while sitting at my work desk!

June 7, 2010 at 1:42 am

wow angela, i’m always blown away by your attention to detail! another great post!!

June 6, 2010 at 6:05 pm

Thanks everyone for sharing and commenting. Sladly yes, this one os personal experience, although my waiting time was closer to ten fun-filled hours. Still, I filled the time looking at the room and the people, knowing it was a perfect setting to blog about. It helped pass the time a bit.

Sorry for everyone who is all too familiar with this one. Still I hope it helps anyone writing hospital ER room scenes (like the awesomo Lisa and Laura!)

June 6, 2010 at 4:55 pm

The crazies really do come out during a full moon. Can’t explain why, but working in an ER, I’ve experienced it!

June 5, 2010 at 11:47 pm

Excellent post – sounds like you were speaking from experience there 🙂

Shauna (murgatr)

June 5, 2010 at 11:41 pm

Great post! I write note like this every time I travel. 🙂

June 5, 2010 at 11:19 pm

The example with the simile made me laugh. I could perfectly visualize the gal working the sanitizer pump.

Actually they were all great. The sampling of senses have a wonderful amount of detail. Even though I hope none of us need to experience an ER visit personally.

June 5, 2010 at 10:12 pm

There’s part of our WIP set in a hospital and this post makes me itch to edit! Great work!

June 5, 2010 at 9:24 pm

Nice post. This is where I lack and it helps to think of it this way. Thanks,

June 5, 2010 at 2:22 pm

This is a place I know only too well. But at least the new Children’s Hospital ER is much nice than the old one.

June 5, 2010 at 12:20 pm

I’ve worked in quite a few hospitals and this is a good assessment. Though depending on the hospital (and the country), you could definitely work in even more smells!

June 5, 2010 at 12:18 pm

This is fantastic! It captured the feel of an ER room perfectly! Great inspiration, thanks!

June 5, 2010 at 11:13 am

Great stuff and timely for me considering how much time I have spent in hospitals recently. There is something about the combination of antiseptic smell and the ever present glare of white halogen lights that really destroys me when I am in a hospital, especially if I have to spend a long, cold night in an Emergency Room corridor with a grieving relative.

June 5, 2010 at 9:59 am

Great job evoking a place we’d rather not spend too much time in!

June 5, 2010 at 8:02 am

Angela, another extraordinary crafting post! Thanks for being so informative time and time again 🙂

Never struggle with Show-and-Tell again. Activate your free trial or subscribe to view the Setting Thesaurus in its entirety, or visit the Table of Contents to explore unlocked entries.

HELPFUL TIP:

Textures and sensations:, possible sources of conflict:, people commonly found in this setting:, setting notes and tips:, related settings that may tie in with this one:, setting description example:, techniques and devices used:, descriptive effects:.

Writing Medical Scenes: Really Useful Links by Paul Anthony Shortt

Paul anthony shortt.

- 24 August 2017

Hospitals, injuries, and medical emergencies are common throughout multiple genres of fiction, and it’s easy to see why. When a character is hurt or sick, this creates instant tension and can have an impact on how the rest of the story goes. Everyone has experiences of injury and illness, whether directly or from a friend or loved one going through it. So we have an immediate connection once we see that a character needs medical help.

But, while everyone knows what it’s like to get hurt or be sick, only a select few of us have the knowledge, experience, and training to know how wounds are treated, what medical practices need to be followed, and how things operate behind the scenes in a hospital. Most of us will get our “knowledge” of this from television, which can frequently be wrong, as we’ve learned in previous articles.

So here are some places you can go to sharpen up your medical knowledge for your writing.

(Please note, none of the articles I’m sharing are intended to replace actual medical training; if you or anyone you know gets hurt or is seriously ill, please seek proper medical help.)

1: Dumbest Medical Mistakes – You can’t beat first-hand knowledge. Allnurses-Breakroom is an online community for nurses, and this discussion thread is a goldmine of little mistakes that you can avoid.

2: How to Write a Hospital Scene – Writethatscene.com offers structure and writing advice for a range of different scenes. In this article they break down the important elements that go into a hospital scene.

3: Not Quite Dead – If your character needs medical attention, what was the reason? You don’t just need to know how their injuries will be treated, you also need to know how their injuries will affect them, directly.

4: Infusing Medical Details Into Your Fiction – This guest post by retired physician Richard Mabry is littered with the kind of small details that help bring your writing to life, along with some good advice about how to present these details in a natural and accessible way.

That’s all for this week. Good luck!

(c) Paul Anthony Shortt

About the author

Paul Anthony Shortt believes in magic and monsters; in ghosts and fairies, the creatures that lurk under the bed and inside the closet. The things that live in the dark, and the heroes who stand against them. Above all, he believes that stories have the power to change the world, and the most important stories are the ones which show that monsters can be beaten.

Paul’s work includes the Memory Wars Trilogy and the Lady Raven Series . His short fiction has appeared in the Amazon #1 bestselling anthology, Sojourn Volume 2.

Website: http://w ww.paulanthonyshortt.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pashortt

Enjoyed this? Read related posts...

Writing Poetry for Beginners: Really Useful Links by Lucy O’Callaghan

Multiple points of view: really useful links by lucy o’callaghan.

Facilitating Children’s Events by Eve McDonnell

Using writing software: really useful links by lucy o’callaghan.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get all of the latest from writing.ie delivered directly to your inbox., featured books.

Your complete online writing magazine.

Guest blogs, courses & events.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and its sequels. Her books are available in five languages, are sourced by US universities, and are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world.

Use bare to describe the hospital room to give your reader some specific insight into how the character is feeling about the situation. Having your character describe the room as bare shows the character is feeling as empty and disconnected as the room physically seems. 4. Stuffy Definition. Oppressive feeling of being closed in. Examples

Here are three complete examples of how to write hospital scenes in different genres. 1. Drama. The hallway of St. Mercy’s was dimly lit, echoing with the soft murmurs of the night shift nurses. Elizabeth walked slowly, her heels clicking on the tiles, each step feeling like an eternity as she approached room 309.

Here are a few questions to think about when writing a character's hospital scene (please note that some of this is for US hospitals only). 1. Is Your Character on the Right Floor? As many people know, hospitals are set up with different patients in different areas of the hospital. There are pediatric floors, adult floors, surgical floors ...

Medical rooms and hospitals are safe, infantalising, dangerous, creepy, life-saving, traumatising places, and I offer them here as examples of what Foucault called ‘ heterotopia ‘. The hospital’s ambiguous relationship to everyday social space has long been a central theme of hospital ethnography. Often, hospitals are presented either as ...

Show who is important to your character and how they share the news with them. It will show a more-in-depth look at your character. The best way to understand anyone is when they are going through a crises. Show your audience who your character truly is and how they handle their news.

Helping writers become bestselling authors. Setting Description: Emergency Waiting Room. June 5, 2010 by ANGELA ACKERMAN. Sight. Automatic sliding doors, beat-up chairs (filled with people who have: broken limbs, cuts, red noses, bruising, scrapes, holding garbage bins to throw up in, are wearing surgical masks, are crying, have been beaten ...

A retractable curtain surrounding the bed or separating beds in a semi-private room. A hospital robe hanging from a peg on the bathroom door. A patient in bed hooked up to various equipment (an IV, a heart monitor, wires leading to other machines, a finger clip, an automatic blood pressure cuff) Nurses and doctors making the rounds.

An empty bed or wheelchair left out in a hallway. Patients shuffling along for exercise, clinging to IV stands. Ice machines, a small kitchen with a fridge for snacks and drinks (within patient wards) Doctors and nurses making rounds, checking diagnostics, dispensing meds, taking blood work, checking in with patients, etc.

Paul Anthony Shortt. 24 August 2017. Hospitals, injuries, and medical emergencies are common throughout multiple genres of fiction, and it’s easy to see why. When a character is hurt or sick, this creates instant tension and can have an impact on how the rest of the story goes. Everyone has experiences of injury and illness, whether directly ...