The Critical Turkey

Essay Writing Hacks for the Social Sciences

How Can I Be Original in my Essay Writing? Critical Analysis and Original Argument

One of the most sought-after, and yet misunderstood, attributes of a social science essay or dissertation is originality. To achieve a grade in the 90s range here at Edinburgh (that is, an A++, an exceptionally good mark), for example, according to our marking descriptors , your essay needs to display ‘an exceptional degree of insight and independent thought’, ‘flair’, and indeed ‘originality’. Independent analysis and originality, however, should not just be a consideration for the higher grade ranges. Rather, this blogpost suggests to think of it as a scale ranging from complete unoriginality (to be avoided) to very high degrees of originality (to be pursued, but within the limits of good scholarship). Below are suggestions how to avoid the former, and how to work towards the latter.

‘Original Contribution’ Originality

Let’s start at the very pinnacle of originality, as this will help you understand why originality is such a priced asset in academia, and where this whole thing is coming from. Before you read this section, though, I want to emphasise that this is not what is normally expected from an undergraduate student essay. You can achieve excellent grades without it. You don’t need this even for an A+ (in Edinburgh terms, an 80s essay), it might just be what takes you from an A+ to an A++ (90s). This level of originality means you have come up with what is often referred to as an ‘original contribution’, a genuinely new idea, typically based on some original data (for example from interviews or questionnaires that you have yourself designed, planned and conducted) that adds genuinely new insight and understanding to the body of existing knowledge. This level of originality is a requirement if you are doing a PhD, it certainly helps with your Master’s or Bachelor’s thesis, but is very unusual and not typically expected in standard essay writing. For professional academics, however, originality is a key currency. It’s what gets their research published in prestigious journals, and forms an important part of academic reputation.

This is so you understand where the people who are teaching you, grading your essays, and writing such marking descriptors are coming from. For them, for us, it’s key to what we do. For you, however, certainly up to the level of where you write your dissertation, this kind of originality is not something you typically need to worry about (there might be exceptions, for example if an assignment specifically asks you to come up with an original research idea).

Still, if you want to go for it, do go for it. What you should know, however, is that you can only do this on the basis of really, really knowing the topic you are writing about very, very well. In order to contribute new insights, you need to know what insights already exist. Sometimes you might have an idea that you haven’t read about anywhere else, but that doesn’t mean someone else hasn’t had that idea first. If it’s already out there, it’s not your original idea, even if you discovered it on your own terms. This means before you can lay claim to your new idea being original, you need to do a lot of reading, and gain a lot of knowledge. Only this extensive knowledge gives you the ability to identify the gaps in the existing knowledge, and whether or not your new idea really does make the contribution you think it makes. In your essay or dissertation, you then also need to explicitly address this, usually through some kind of literature review that summarises the existing ideas and arguments, identifies the gaps of knowledge, and explains how your new idea addresses these gaps.

Sounds tough? It is. And I haven’t even started on how to design your own research project, collect your own data etc. It is indeed beyond the scope of this blogpost. It needs a lot of focus and dedication, and that is why this kind of originality is usually reserved for bigger research projects, in which you have time to do all that digging, and time to do all that original research. For a standard university essay, it means a lot of extra work for marginal gains.

A more realistic view of originality in undergraduate essays

The good news however, is that the above is only one kind of originality. There is a different kind that can be employed, and that can be used throughout your essay. This is not so much a matter of introducing new data or ideas (ie what you put in your essay), but a question of how you discuss existing information, how you write, how you assemble your argument, how you bring the readings into discussion with each other etc. The focus here indeed shifts from the what to the how .

What to avoid

Let’s start with what you should try to avoid. On this end of the spectrum there is unoriginal writing. This is writing that mostly just repeats what others have written before, with little of your own input or critical discussion. Such an essay will make the usual, obvious points and not add much to it. It can show itself, for example, in entire paragraphs being mere summaries of one of the readings, without integrating it with the essay argument or with other relevant readings. In other cases, there might be integration with other readings or the argument, but only in a way that someone else (another reading or the lecture on the topic) has done before. This re-telling of parts of a lecture is indeed not too uncommon in weaker essays, and at times the exact same references and sometimes even the exact same quotes are used as the lecture does.

For this case especially, a word of warning: This last example is not just unoriginal, it is poor scholarship and potentially plagiarism. You must not just retell the story in the same way someone else has, whether this is the lecture or another reading, pretending it’s your own work.

Avoid, then, mere summaries of readings. And avoid summaries of other people’s summaries of other literature. At best, this type of unoriginality will make the difference between a B and a C (ie it is typically what prevents an essay from reaching the B or 60s level in our marking scheme). At worst, it is plagiarism, and will get you into trouble.

Critical Analysis and Original Argument

How to write in an original way, then? To start with, there are two layers to consider. The first one is critical analysis, the second is original argument. Both are expressed in both the macro-organisation of your essay and the micro-level of how you write.

Critical analysis

I have written in more detail on how to be critical in social science essay writing in this blogpost . Do read it if you want more detail. To summarise the main points, first, you need to critically engage with the literature. This means questioning the assumptions different authors build on, having a closer look at the methodology they use, contextualising them with other studies that have been done on the topic, but also understanding the context in which the work has been produced, and how this might have influenced the author and their motives. Do not misunderstand critical engagement with disagreeing with the author. You might disagree, but there is also such a thing as critical appreciation, in which you agree with someone precisely because you have examined their work in detail, and have found them to be convincing. This, too, demonstrates critical engagement. This first element of critical analysis mostly shows itself on the micro-level of how your write your essay, how you present your ideas and those of others, always with an attention to the details of the studies you present, and an awareness of different interpretations.

Second, critical analysis can mean formulating a critique of the social/political phenomenon you are looking at. This means asking the power question: How does power, and how do hierarchies and inequalities (economic, political, symbolic etc.) show themselves in how, for example, poverty is discussed in media discourses, policy responses to climate change, or the design of school curricula? This second element of critical analysis can play a key part in how you organise your essay on the macro-level, and how you assemble your overall argument. You can thus organise and structure your essay around a key ctitique that puts into focus the role of such power and hierarchy relations.

Original Argument

And this brings me to the point on ‘original argument’. It depends a little on the essay question, but it is almost always a good idea to formulate an argument, an arguable statement relating to the essay question, introduced in the introduction, and serving as a lynchpin throughout your essay. This could be, for example, ‘this essay argues that tabloid media discourses on poverty are deliberately designed by their owners to blame poverty on the poor, and legitimise welfare cuts and a low-tax, low-spend government’, or it could be ‘that the resistance by policy-makers against sustainable policies, particularly in the US, can be explained by the economic power and political influence the fossil fuel industry still holds, both in the form of financing so-called ‘science’, and through lobbying various levels of government’. Or it could be ‘This essay will argue that the way British history is taught, in particular in its ‘small island’ version introduced by the conservative government in English schools, aims at isolating British history from its colonial context, and obscuring the role of colonial exploitation in the development of the modern British state’.

Let’s keep some perspective here. The above examples are very detailed and nuanced thesis statements that you might see in an A+ essay – something you maybe want to strive for, if your ambitions are that way inclined. But even more reduced versions (e.g. ‘I am going to argue that the school curriculum is an expression of still-existing colonial relations’ or ‘poverty discourses serve to legitimise welfare cuts’) will go a long way. The important thing is that whatever your argument is, it should indeed be arguable, that is, one should be able to argue against it. And indeed, as you then proceed to write your essay, you should anticipate various counter-arguments, what someone else might say and what evidence they might use to argue against you. Address these counter-arguments as appropriate, and show why you find them less convincing.

The essay, then, in a macro-sense, can be organised around such an argument. On the micro-level of how this shows itself as you write along, you then need to develop this argument as your essay proceeds. This is done primarily through signposting, adding a sentence or two at the end of each point or paragraph, making the connections between the different points clearer, and how they relate to the argument. Signposting is usually understood as improving the flow of the essay. This is indeed one of its functions. There is another function, however, which is that it actually helps you develop, and bring to the fore, what your argument is. When it finally comes to the conclusion at the end of your essay, you merely need to bring the different strings of the argument together, and put them into context with the essay or research question.

Final Thoughts

Both critical analysis and original argument take you beyond merely reproducing what is already out there. They help you develop your own take on things, and put your own stamp on the essay. They will demonstrate your credentials as an independent, critical thinker. They are the keys that will help you unlock ‘originality’ in your essay.

Part 2 of ‘How to be original’ will go a step further, and suggest two techniques for turbocharging your originality, (a) using case studies and (b) theoretical frameworks. Stay tuned for updates.

One thought on “How Can I Be Original in my Essay Writing? Critical Analysis and Original Argument”

- Pingback: How can I write an effective Introduction and Conclusion? Part 1: Introduction – a formula that almost always works – The Critical Turkey

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

HTML Text How Can I Be Original in my Essay Writing? Critical Analysis and Original Argument / The Critical Turkey by blogadmin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Plain text How Can I Be Original in my Essay Writing? Critical Analysis and Original Argument by blogadmin @ is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Report this page

To report inappropriate content on this page, please use the form below. Upon receiving your report, we will be in touch as per the Take Down Policy of the service.

Please note that personal data collected through this form is used and stored for the purposes of processing this report and communication with you.

If you are unable to report a concern about content via this form please contact the Service Owner .

How to Write the Perfect Essay

06 Feb, 2024 | Blog Articles , English Language Articles , Get the Edge , Humanities Articles , Writing Articles

A Step-by-Step Guide to the Perfect Essay

Step 1: plan.

This may sound time-consuming, but if you make a really good plan, you’ll actually save yourself time when it comes to writing the essay, as you’ll know where your answer is headed and won’t write yourself into a corner.

Don’t worry if you’re stuck at first! Jot down a few ideas anyway and chances are the rest will follow. I find it easiest to make a mind map, with each new “bubble” representing one of my main paragraphs. I then write quotations which will be useful for my analysis around the bubble.

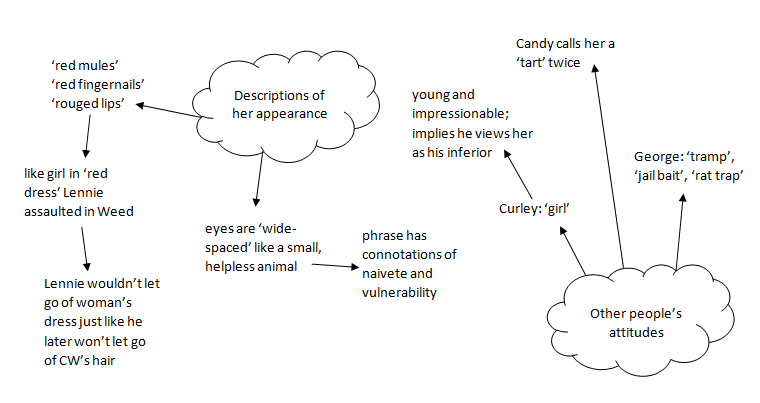

For example, if I was answering the question, “To what extent is Curley’s wife portrayed as a victim in Of Mice and Men ?”, I might begin with a mind map that looks something like this:

You can keep adding to this plan, crossing bits out and linking the different bubbles when you spot connections between them. Even though you won’t have time to make a detailed plan under exam conditions, it can be helpful to draft a brief one, including a few key words, so that you don’t panic and go off topic when writing your essay.

If you don’t like the mind map format, there are plenty of others to choose from: you could make a table, a flowchart, or simply a list of bullet points.

Discover More

Thanks for signing up, step 2: have a clear structure.

Think about this while you’re planning: your essay is like an argument or a speech. It needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question.

Start with the basics! It’s best to choose a few major points which will become your main paragraphs. Three main paragraphs is a good number for an exam essay, since you’ll be under time pressure.

If you agree with the question overall, it can be helpful to organise your points in the following pattern:

- YES (agreement with the question)

- AND (another YES point)

- BUT (disagreement or complication)

If you disagree with the question overall, try:

- AND (another BUT point)

For example, you could structure the Of Mice and Men sample question, “To what extent is Curley’s wife portrayed as a victim in Of Mice and Men ?”, as follows:

- YES (descriptions of her appearance)

- AND (other people’s attitudes towards her)

- BUT (her position as the only woman on the ranch gives her power as she uses her femininity to her advantage)

If you wanted to write a longer essay, you could include additional paragraphs under the YES/AND categories, perhaps discussing the ways in which Curley’s wife reveals her vulnerability and insecurities, and shares her dreams with the other characters. Alternatively, you could also lengthen your essay by including another BUT paragraph about her cruel and manipulative streak.

Of course, this is not necessarily the only right way to answer this essay question – as long as you back up your points with evidence from the text, you can take any standpoint that makes sense.

Step 3: Back up your points with well-analysed quotations

You wouldn’t write a scientific report without including evidence to support your findings, so why should it be any different with an essay? Even though you aren’t strictly required to substantiate every single point you make with a quotation, there’s no harm in trying.

A close reading of your quotations can enrich your appreciation of the question and will be sure to impress examiners. When selecting the best quotations to use in your essay, keep an eye out for specific literary techniques. For example, you could highlight Curley’s wife’s use of a rhetorical question when she says, a”n’ what am I doin’? Standin’ here talking to a bunch of bindle stiffs.” This might look like:

The rhetorical question “an’ what am I doin’?” signifies that Curley’s wife is very insecure; she seems to be questioning her own life choices. Moreover, she does not expect anyone to respond to her question, highlighting her loneliness and isolation on the ranch.

Other literary techniques to look out for include:

- Tricolon – a group of three words or phrases placed close together for emphasis

- Tautology – using different words that mean the same thing: e.g. “frightening” and “terrifying”

- Parallelism – ABAB structure, often signifying movement from one concept to another

- Chiasmus – ABBA structure, drawing attention to a phrase

- Polysyndeton – many conjunctions in a sentence

- Asyndeton – lack of conjunctions, which can speed up the pace of a sentence

- Polyptoton – using the same word in different forms for emphasis: e.g. “done” and “doing”

- Alliteration – repetition of the same sound, including assonance (similar vowel sounds), plosive alliteration (“b”, “d” and “p” sounds) and sibilance (“s” sounds)

- Anaphora – repetition of words, often used to emphasise a particular point

Don’t worry if you can’t locate all of these literary devices in the work you’re analysing. You can also discuss more obvious techniques, like metaphor, simile and onomatopoeia. It’s not a problem if you can’t remember all the long names; it’s far more important to be able to confidently explain the effects of each technique and highlight its relevance to the question.

Step 4: Be creative and original throughout

Anyone can write an essay using the tips above, but the thing that really makes it “perfect” is your own unique take on the topic. If you’ve noticed something intriguing or unusual in your reading, point it out – if you find it interesting, chances are the examiner will too!

Creative writing and essay writing are more closely linked than you might imagine. Keep the idea that you’re writing a speech or argument in mind, and you’re guaranteed to grab your reader’s attention.

It’s important to set out your line of argument in your introduction, introducing your main points and the general direction your essay will take, but don’t forget to keep something back for the conclusion, too. Yes, you need to summarise your main points, but if you’re just repeating the things you said in your introduction, the body of the essay is rendered pointless.

Think of your conclusion as the climax of your speech, the bit everything else has been leading up to, rather than the boring plenary at the end of the interesting stuff.

To return to Of Mice and Men once more, here’s an example of the ideal difference between an introduction and a conclusion:

Introduction

In John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men , Curley’s wife is portrayed as an ambiguous character. She could be viewed either as a cruel, seductive temptress or a lonely woman who is a victim of her society’s attitudes. Though she does seem to wield a form of sexual power, it is clear that Curley’s wife is largely a victim. This interpretation is supported by Steinbeck’s description of her appearance, other people’s attitudes, her dreams, and her evident loneliness and insecurity.

Overall, it is clear that Curley’s wife is a victim and is portrayed as such throughout the novel in the descriptions of her appearance, her dreams, other people’s judgemental attitudes, and her loneliness and insecurities. However, a character who was a victim and nothing else would be one-dimensional and Curley’s wife is not. Although she suffers in many ways, she is shown to assert herself through the manipulation of her femininity – a small rebellion against the victimisation she experiences.

Both refer back consistently to the question and summarise the essay’s main points. However, the conclusion adds something new which has been established in the main body of the essay and complicates the simple summary which is found in the introduction.

Hannah is an undergraduate English student at Somerville College, University of Oxford, and has a particular interest in postcolonial literature and the Gothic. She thinks literature is a crucial way of developing empathy and learning about the wider world. When she isn’t writing about 17th-century court masques, she enjoys acting, travelling and creative writing.

Recommended articles

Best Universities to Study Medicine in the World

A degree in Medicine spans many years, so it’s important to make a good choice when committing yourself to your studies. This guide is designed to help you figure out where you'd like to study and practise medicine. For those interested in getting a head start, the...

What Is A Year Abroad?

One of the great opportunities offered to UK university students is taking a year abroad. But what does this involve? Who can do it? What are some of the pros and cons? In our year abroad guide, we’ll explain some of the things to bear in mind when considering this...

The Ultimate Guide To Summer Internships

Are you eager to make the most of your summer break and jumpstart your career? There are so many productive things students can do in the summer or with their school holidays, and an internship is one of the most valuable! A summer internship could be the perfect...

Does my paper flow? Tips for creating a well-structured essay.

by Jessica Diaz

A sure way to improve your paper is to strengthen the way you present your argument. Whether you only have a thesis statement or already have a fully-written essay, these tips can help your paper flow logically from start to finish.

Going from a thesis statement to a first outline

Break down your thesis statement

No matter what you are arguing, your thesis can be broken down into smaller points that need to be backed up with evidence. These claims can often be used to create a ready outline for the rest of your paper, and help you check that you are including all the evidence you should have.

Take the following thesis statement:

Despite the similarities between the documentaries Blackfish and The Cove , the use of excessive anthropomorphism in Blackfish allowed it to achieve more tangible success for animal rights movements, illustrating the need for animal rights documentaries to appeal to human emotion.

We can break the thesis down into everything that needs to be supported:

Despite the similarities between the documentaries Blackfish and The Cove , the use of excessive anthropomorphism in Blackfish allowed it to achieve more tangible success for animal rights movements , illustrating the need for animal rights documentaries to appeal to human emotion .

In the paper, we have to (1) explain and support the similarities between the two documentaries, (2) provide support for excessive anthropomorphism in Blackfish , (3) show that Blackfish achieved more tangible success than The Cove , and (4) demonstrate the importance of human emotion in animal documentaries.

Already, we have four main points that can serve as the backbone for an essay outline, and they are already in an order that makes some intuitive sense for building up the argument.

It is likely that you will need to rearrange, expand, or further break down the outline. For example, in this case we would probably need to add a paragraph that explains anthropomorphism. We also might want to move the section on differences in animal rights success earlier so that it contrasts with the similarities between the films. However, having this starting structure and identifying the main sections of the paper can allow you to go ahead and start writing!

Checking that your argument builds

Reverse outline

While writing, it is often hard to take a step back and assess whether your paper makes sense or reads well. Creating a reverse outline can help you get a zoomed-out picture of what you wrote and helps you see if any paragraphs or ideas need to be rearranged.

To create a reverse outline, go through your paper paragraph-by-paragraph. For each one, read it and summarize the main point of the paragraph in 3-5 words. In most cases, this should align closely with the topic sentence of that paragraph. Once you have gone through the entire paper, you should end up with a list of phrases that, when read in order, walk through your argument.

Does the order make sense? Are the ideas that should go together actually next to each other? Without the extra clutter, the reverse outline helps you answer these questions while looking at your entire structure at once.

Each line of your reverse outline should build on the last one, meaning none of them should make sense in isolation (except the first one). Try pretending you don’t know anything about this topic and read one of your paragraph phrases at random (or read it to someone else!). Does it make sense, or does it need more context? Do the paragraphs that go before it give the context it needs?

The reverse outline method and the line of thinking detailed above help put you in the mind of your reader. Your reader will only encounter your ideas in the order that you give it to them, so it is important to take this step back to make sure that order is the right one.

Quick Links

- Schedule an Appointment

- English Grammar and Language Tutor

- Harvard Guide to Using Sources

- Departmental Writing Fellows

- Writing Advice: The Harvard Writing Tutor Blog

Welcome to the Barker Underground!

The official blog of the Harvard Writing Center. Check back for writing advice from tutors past and present.

IMAGES

VIDEO