College Essay: My Parents’ Sacrifice Makes Me Strong

After living in Texas briefly, my mom moved in with my aunt in Minnesota, where she helped raise my cousins while my aunt and uncle worked. My mom still glances to the building where she first lived. I think it’s amazing how she first moved here, she lived in a small apartment and now owns a house.

My dad’s family was poor. He dropped out of elementary school to work. My dad was the only son my grandpa had. My dad thought he was responsible to help his family out, so he decided to leave for Minnesota because of many work opportunities .

My parents met working in cleaning at the IDS C enter during night shifts. I am their only child, and their main priority was not leaving me alone while they worked. My mom left her cleaning job to work mornings at a warehouse. My dad continued his job in cleaning at night.

My dad would get me ready for school and walked me to the bus stop while waiting in the cold. When I arrived home from school, my dad had dinner prepared and the house cleaned. I would eat with him at the table while watching TV, but he left after to pick up my mom from work.

My mom would get home in the afternoon. Most memories of my mom are watching her lying down on the couch watching her n ovelas – S panish soap operas – a nd falling asleep in the living room. I knew her job was physically tiring, so I didn’t bother her.

Seeing my parents work hard and challenge Mexican customs influence my values today as a person. As a child, my dad cooked and cleaned, to help out my mom, which is rare in Mexican culture. Conservative Mexicans believe men are superior to women; women are seen as housewives who cook, clean and obey their husbands. My parents constantly tell me I should get an education to never depend on a man. My family challenged machismo , Mexican sexism, by creating their own values and future.

My parents encouraged me to, “ ponte las pilas ” in school, which translates to “put on your batteries” in English. It means that I should put in effort and work into achieving my goal. I was taught that school is the key object in life. I stay up late to complete all my homework assignments, because of this I miss a good amount of sleep, but I’m willing to put in effort to have good grades that will benefit me. I have softball practice right after school, so I try to do nearly all of my homework ahead of time, so I won’t end up behind.

My parents taught me to set high standards for myself. My school operates on a 4.0-scale. During lunch, my friends talked joyfully about earning a 3.25 on a test. When I earn less than a 4.25, I feel disappointed. My friends reacted with, “You should be happy. You’re extra . ” Hearing that phrase flashbacks to my parents seeing my grades. My mom would pressure me to do better when I don’t earn all 4.0s

Every once in awhile , I struggled with following their value of education. It can be difficult to balance school, sports and life. My parents think I’m too young to complain about life. They don’t think I’m tired, because I don’t physically work, but don’t understand that I’m mentally tired and stressed out. It’s hard for them to understand this because they didn’t have the experience of going to school.

The way I could thank my parents for their sacrifice is accomplishing their American dream by going to college and graduating to have a professional career. I visualize the day I graduate college with my degree, so my family celebrates by having a carne asada (BBQ) in the yard. All my friends, relatives, and family friends would be there to congratulate me on my accomplishments.

As teenagers, my parents worked hard manual labor jobs to be able to provide for themselves and their family. Both of them woke up early in the morning to head to work. Staying up late to earn extra cash. As teenagers, my parents tried going to school here in the U.S . but weren’t able to, so they continued to work. Early in the morning now, my dad arrives home from work at 2:30 a.m ., wakes up to drop me off at school around 7:30 a.m . , so I can focus on studying hard to earn good grades. My parents want me to stay in school and not prefer work to head on their same path as them. Their struggle influences me to have a good work ethic in school and go against the odds.

© 2024 ThreeSixty Journalism • Login

ThreeSixty Journalism

A multimedia storytelling program for Minnesota youth, ThreeSixty is grounded in the principles of journalism and focused on contributing to more accurate narratives and representative newsrooms.

- Relationships

8 Challenges of Growing Up as a Second-Generation Immigrant

Things about having immigrant parents that no one talks about..

Posted January 10, 2023 | Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

- Take our Relationship Attachment Test

- Find a Codependency Therapist

- As a child to immigrant parents, you might have automatically blamed yourself for their struggles.

- If you were born to immigrant parents, you might have lived "between" two cultures all your life.

- Overcoming the trauma of being the second generation of immigrants is not only possible but essential.

Second-generation immigrants often wish their parents had been different. You may long for parents who share your intellectual level, values, and political or spiritual beliefs. In this post, we will discuss some of the challenges of having immigrant parents, including the ones that are often tabooed.

1. The Heaviness of Unspoken Guilt . Children naturally blame themselves for their parents' pain. Your unwarranted guilt is worse as a second-generation immigrant when you know that your immigrant parents came to a new country to "give you a better life.” As a child, you might have automatically blamed yourself for your parents' struggles because you thought you did something wrong or did not help enough. So you studied harder, did more housework, counseled them, and may even have become their emotional punching bag.

Unconscious guilt can manifest itself in unexpected ways. Even now, you may have trouble taking care of yourself and managing money. You may work too much and feel guilty when you relax or have fun. Despite your success, you feel like an imposter. You are wary of being vulnerable even in close friendships and romantic relationships .

2. Rootless Without Home. If you were born to immigrant parents, you might have lived "between" two cultures all your life. Unlike your parents, your sense of self does not revolve around your heritage from the old country. But neither is it a purely Eurocentric integration into the new country.

You may have been conditioned to behave a certain way toward your relatives but a very different way toward your friends. You have not had the opportunity to explore and solidify your identity if you constantly hide one or more aspects of your personality to fit in, like a chameleon. Even now, you could be struggling with identity confusion, having difficulty deciding on important life goals such as a career or a romantic partner.

3. The Intellectual Divide. You may find that while other families may have stimulating discussions about current events, your parents seem rooted in the past and unable to see beyond their narrow perspective. Your parents may have shown no understanding of diversity, feminism, the dark side of capitalism, etc., and so there are no intellectual or political discussions about these issues at home. The intellectual distance between you and your parents can make even the most mundane conversations tedious, if not painful.

You may feel compelled to challenge your parents when they say or do things against your values. However, if you try to correct them, they may become defensive and either avoid you or become combative.

Although you respect and love your parents very much, you may find it difficult to relax and be yourself around them. You feel existentially alone in your own home, but you have no one to talk to about it because it is such a taboo.

4. Not Seen for Who You Are. Your immigrant parents may not have been exposed to global perspectives that would help them understand your place in the world. They think you are "good" because you have good grades or a steady job, but that misses the point. They do not know how to appreciate your ability to think independently, your willingness to stand up for what you believe in, your commitment to social justice, or your courage to defend the truth.

When it comes to our own family, it can be exceedingly hurtful to hear that we are "too much" (too emotional, too dramatic, too demanding, too intense, too sensitive). The pain of not being recognized by, or even being rejected by, our own family can cause immeasurable suffering that lasts a lifetime, even if we try to rationalize it by saying that we are materially well provided for.

5. Trapped in Codependency. It is sadly common for parents and children in immigrant families to develop an unhealthy level of codependency. You may feel obligated to put your parent's needs before your own, blame yourself for their problems, worry about them constantly, feel responsible for their happiness , and neglect your own needs. Part of you wants to rescue or help your parents, but you're also angry and resentful because their needs stunted you.

6. Constant Disapproval. Your immigrant parents may judge who you're with, what you do, whether you're single, married, polyamorous , etc. Worse, you know that many of your so-called "choices" in fact just represent who you are. Parents may reject you because this new information contradicts what they are sure they know. Their unconscious bias hurts you, even if they don't mean to. Their casual comments, facial expressions, or punitive silences may reveal prejudices even when they say nothing.

7. Navigating Life with " Learned Helplessness ." If you were born into an immigrant family, you might have witnessed or experienced institutional discrimination , microaggressions , and racism too early, too soon, perhaps even as a child. Psychologists use the term "learned helplessness" to describe the effects of being regularly exposed to systemic oppression and injustice without being able to do anything about it. You may have internalized the idea that no matter how hard you try, you will ultimately get nowhere. This can affect your self-esteem and your ability to pursue goals as an adult. You may also feel powerless in the face of injustice or corruption. You cannot just dismiss them or pretend they do not exist, but you're paralyzed by an overwhelming sense that it is impossible to change the world.

8. Unmet Emotional Needs. Your immigrant parents may have struggled, but they never modeled what it was like to show or express feelings. What if grief kept them from working? What if they let out all their emotions and cannot control them, leading to a depressive breakdown? Because of these fears, they felt they had to suppress any burgeoning emotions. So, when you show vulnerable feelings such as shame or sadness, they do not know what to do. They may try to silence your feelings, so they do not have to face their own. They may tell you it's "bad" to show emotion , or punish or silence you to keep you from being expressive and spontaneous.

Furthermore, with a general lack of mental health awareness, your immigrant parents may misunderstand your depression as laziness, your eating disorder as defiance, your ADHD as a character flaw, etc. They may be unfamiliar with the idea of seeing a therapist or psychiatrist, let alone paying for such services.

Internalized beliefs that it is unacceptable to express feelings, have emotional needs, or be vulnerable can prevent you from developing meaningful relationships or finding fulfillment in life.

Discovering Strength and Peace as a Second-Generation Immigrant

You wish you had parents with whom you could have open, honest conversations about life and the world. But you are silenced for your loneliness because it feels wrong to be ungrateful. Transgenerational trauma can have devastating effects. But since we can't blame our parents forever, we must heal ourselves. Consider these questions: How do you approach authorities? What's your money mindset? Do you feel guilty when you outshine your siblings or parents? How well can you express vulnerabilities with intimate partners?

You may feel guilty or fearful when it's time to separate yourself from your parents' values, even if you logically know your feelings have no logical basis. If you follow your heart, you are afraid to break theirs. But if you ignore the existential call to be yourself, you may become physically or emotionally ill.

As you enter your second half of life, overcoming the trauma of being the second generation of immigrants is not only possible but essential. You can thrive by embracing repressed emotions and gifts. By acknowledging your history and struggles, sharing your true feelings, and overcoming generational trauma , you can build bridges between yourself and your family and contribute to your community.

Liem, R. (1997). Shame and guilt among first-and second-generation Asian Americans and European Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 28(4), 365-392.

M Rothe, E., J Pumariega, A., & Sabagh, D. (2011). Identity and acculturation in immigrant and second generation adolescents. Adolescent psychiatry, 1(1), 72-81.

Phipps, R. M., & Degges‐White, S. (2014). A new look at transgenerational trauma transmission: Second‐generation Latino immigrant youth. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 42(3), 174-187.

Pumariega, A. J., Rothe, E., & Pumariega, J. B. (2005). Mental health of immigrants and refugees. Community mental health journal, 41(5), 581-597.

Imi Lo, MA, is a consultant and psychotherapist with masters degrees in Mental Health and Buddhist Studies. She is the author of Emotional Sensitivity and Intensity and The Gift of Intensity and runs Eggshell Therapy and Coaching.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

When we fall prey to perfectionism, we think we’re honorably aspiring to be our very best, but often we’re really just setting ourselves up for failure, as perfection is impossible and its pursuit inevitably backfires.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Home — Application Essay — National Universities — How Having Immigrant Parents Changed Me: Personal Experience

How Having Immigrant Parents Changed Me: Personal Experience

- University: Texas A&M University

About this sample

Words: 869 |

Published: Jul 18, 2018

Words: 869 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

In this essay, I will explore the profound impact of having immigrant parents on my upbringing and perspective. Growing up, I had the unique opportunity to bridge the gap between my life in the United States and the experiences of my parents in Belarus, a country with its own set of challenges and hardships. These contrasting worlds have shaped my values, work ethic, and resilience, ultimately influencing the person I have become today.

Say no to plagiarism.

Get a tailor-made essay on

'How Having Immigrant Parents Changed Me: Personal Experience'

6:00 AM, small industrial town of Zhodino, Belarus. Summer 2008. I reluctantly boarded the bus, immediately noticing that it was absolutely packed. The bus, of course, was to my grandmother’s dacha, a cottage where she grew and tended to what I have always considered to be an absurd amount of crops, all by herself. After standing cramped like sardines for an hour, and then walking along a muddy path for twenty minutes, we finally arrived at my grandparents’ dacha. I was absolutely exhausted, but we were just getting started. At any given moment in the next seven hours I was being forced to dig or pick some sort of crop out of the ground.

Through all of my tantrums and complaining that day, my grandmother continued working and just kept telling me to do the same. When 2 PM finally rolled around, I was so happy to be going back to her apartment that I found the energy to run through most of the muddy path. Once we got to the bus stop, however, I was devastated to learn that we were not going home, but to the local farmer’s market. My grandmother spent the next 2 hours selling the crops she had unearthed that day, while I was passed out with my face on the raggedy old tablecloth she used.

For my parents, that full day of manual labor was a very common way to spend their summer days growing up. Before they immigrated to the United States in 1998, they had grown up in Belarus, which was a part of Soviet Union at the time. Even as a self-reliant nation today, the country continues to struggle under a dictatorship; a relic of the totalitarian Past. Not quite North Korea, but with certain similarities. And while I was raised in a much more financially stable household in Texas, my parents helped me to understand how fortunate I was by bringing me back to their home country with them most summers growing up.

I have seen what it is like to stay in a country in crisis, and after every summer I have returned home to Texas with a more positive outlook on life. I’ve been able to encourage myself through even the most stressful points in my life by simply thinking about how much more serious my problems may be if my parents hadn’t worked as hard as they did to make it out of Belarus. If I hadn’t returned to Belarus every summer and seen how food prices were always rising and how my grandmother’s pension was always dropping, it is unlikely that I would be able to understand other people’s misfortunes and suffering as well as I am now. Because of these humbling experiences, I’ve spent a plentiful amount of time volunteering for CCA Food Pantry, the Texas Ramp Project, and the North Texas Food Bank.

Since my parents have always had a serious understanding of what can happen without self-sufficiency and hard work, I was raised somewhat differently than most of the kids around me were. While my some of my friends’ parents would essentially nanny them through many of their problems, I was taught from a very young age that I would have to take care of certain things on my own. When I was eight years old and told my dad I was interested in woodworking, he gave me a hammer, nails, and some wood and said “Build a table then.” When I told my mom I wanted to join my first basketball league when I was seven, she told me “That’s great, but you’ll have to sign up yourself, I’m very busy at work right now.”

Keep in mind: This is only a sample.

Get a custom paper now from our expert writers.

Events like these were clearly nowhere near traumatic, and my parents have always given me everything I’ve ever needed. However, they did help me to learn self-sufficiency and perseverance, because while I had never built anything in my life or used a computer for anything other than gaming, I had to figure these problems out on my own. Because of the way I was raised, I realized from a young age that complaining wouldn’t get me anywhere. Resiliency, however, would. I eventually built that table and figured out how to sign up for that league, and while the table only had one leg and I accidentally sent my registration to the YMCA in Arkansas, I learned through episodes like these that if I was dedicated enough, I could achieve my goals. Being raised by two immigrant parents has been very influential in my maturation. The values they have instilled in me, along with the perspective I’ve gained by visiting their old homes in Belarus, have made me a more determined and unselfish person. I would not be where I am today if it wasn’t for my unorthodox upbringing.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: National Universities

+ 126 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Are you interested in getting a customized paper?

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on National Universities

I was sitting with my teammates in the Denver airport after yet another trip to Boulder, Colorado for a running camp. The week had been successful, and most of my memories made on the trip were good ones. There were, however, [...]

It was ironic that my dad always called me “Rock,” because a year ago I felt like a piece of clay. I remember the nights I spent in my room, crying in the silence, mulling over the value of my life. It was only months after my [...]

My father was born in a little village in the south of France called Le Chambon in 1944. In that village, 5,000 Christians saved 5,000 Jews, including my grandfather, my grandmother, and my father. Last summer, I visited Le [...]

A home should serve as a transitional space between shelter and the outdoors. In all of the structures that I design, I try to include walls full of windows that will allow in natural light. These windows help to integrate [...]

I have always been fascinated by the complexities of gender and sexuality. As a society, we have made tremendous progress in recent years in terms of accepting and embracing diverse gender identities and sexual orientations. [...]

Eyes lock in on the cross and follow it down the aisle as its bearer leads the procession until the last person of the seemingly endless line grabs the entire congregation’s attention. Entering the back of the sanctuary, Father [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Growing Up in America With Immigrant Parents

I wrote about how my parents taught me to love who I am by being true to myself.

Being Assyrian has always been a huge part of my identity. As a child I felt so embarrassed to be who I am. No one had ever taught me to feel that way, I just didn't like how different my life seemed to be, compared to the other kids from my school. I had a unibrow and I had to take ESL classes because I was raised learning a mix of Aramaic and English. I refused to speak Aramaic publically. I was so ashamed of all of these things for some reason. I just wanted to be like the other kids at my school, blonde hair and blue eyes with a “normal” name. I hated my brown hair, brown eyes, my unibrow, and my “odd” name (Amena).

As I grew older, I started to become more accepting towards my background. This started happening around middle school age. I realized that there was no reason for me to be ashamed. I still felt different though. No matter how much I adapted I was still being raised differently from everyone else. My parents were always more strict that the others. They wouldn't let me hangout with certain people, I was never allowed to go to sleepovers, I couldn't wear certain clothes because they were “too revealing” even if everyone else in my grade was allowed to. I think that these are just things that you have to deal with when you have Middle Eastern parents. Things that were so normal for every other kid seemed to be so unbelievably offensive to my parents. I used to think it was so frustrating to deal with this.

To this day I still struggle with their grip. I can sometimes understand and appreciate why they raised me this way. As immigrants in America they dealt with a lot of the same feelings as I felt when I was younger. They struggled with not fitting in as a child just like me. When my mother's family moved here she was only a year old. She was raised in Davisburg Pennsylvania, she didn't have anyone to relate to around her other than her siblings. She had it so much worse than I did but today she loves being who she is. My dad moved to America when he was nine. He was raised in Detroit Michigan and in attempt to fit in he had to sacrifice some of his identity. Today I see him as the one of the most confident, down to earth people on this planet. He always stresses to me that I couldn't make a bigger mistake that being fake with myself. I think that all this time my parents were trying to point me in that direction. They wanted me to love who I am. They didn't want me to try so hard to be something i'm not just because I wanted to blend in. Instead they taught me how to stay true to myself and how to be comfortable in my own skin

Although it was frustrating at times I think overall it benefited me to be raised this way. I learned to do what's best for myself and have good judgment. They taught me to be comfortable in my own skin and put myself first. They taught me that no ones opinion matters except my own. Here in America you are able to do almost anything you'd want as long as you give it your all. Being true to myself is the only way for me identify my dreams. My parents wanted to make sure that I had my priorities straight so that I can focus on what's important.

It's ironic how I learned one of the most important American values from my immigrant parents. I thought this whole time that their “Middle Eastern morals” would separate me from everyone else but really they were what made me feel comfortable with myself now. They really have taught me so much about how to live a good, happy, healthy, American life! Today I live to please myself and the ones I love only. I know now that I don’t have to attempt to make everyone like me. I do what I please while still being reasonable and respectful. The only person really judging me is myself. I live by these morals and i couldn't be any more stress free.

- Written by Amena

- From Royal Oak High School

- In Michigan

- Group 7 Created with Sketch Beta. Upvote

- immigration

- Report a problem

Royal Oak High School Ready for Fun

ELA 11 6th Hour

More responses from Ready for Fun

More responses from royal oak high school, more responses from michigan, more responses from "division", "dream", "immigration", and "love ".

- Login / Sign Up

Fearless journalism needs your support now more than ever

Our mission could not be more clear and more necessary: We have a duty to explain what just happened, and why, and what it means for you. We need clear-eyed journalism that helps you understand what really matters. Reporting that brings clarity in increasingly chaotic times. Reporting that is driven by truth, not by what people in power want you to believe.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

- Criminal Justice

My immigrant family achieved the American dream. Then I started to question it.

by Amanda Machado

In summer 2007, I returned home from my freshman year at Brown University to the new house my family had just bought in Florida. It had a two-car garage. It had a pool. I was on track to becoming an Ivy League graduate, with opportunities no one else in my family had ever experienced. I stood in the middle of this house and burst into tears. I thought: We’ve made it.

That moment encapsulated what I had always thought of the “American dream.” My parents had come to this country from Mexico and Ecuador more than 30 years before, seeking better opportunities for themselves. They worked and saved for years to ensure my two brothers and I could receive a good education and a solid financial foundation as adults. Though I can’t remember them explaining the American dream to me explicitly, the messaging I had received by growing up in the United States made me know that coming home from my first semester at a prestigious university to a new house meant we had achieved it.

- I spent the last 15 years trying to become an American. I've failed.

And yet, now six years out of college and nearly 10 years past that moment, I’ve begun questioning things I hadn’t before: Why did I “make it” while so many others haven’t? Was this conventional version of making it what I actually wanted? I’ve begun to realize that our society’s definition of making it comes with its own set of limitations and does not necessarily guarantee all that I originally assumed came with the American dream package.

I interviewed several friends from immigrant backgrounds who had also reflected on these questions after achieving the traditional definition of success in the United States. Looking back, there were several things we misunderstood about the American dream. Here are a few:

1) The American dream isn’t the result of hard work. It’s the result of hard work, luck, and opportunity.

Looking back, I can’t discount the sacrifices my family made to get where we are today. But I also can’t discount specific moments we had working in our favor. One example: my second-grade teacher, Ms. Weiland. A few months into the year, Ms. Weiland informed my parents about our school’s gifted program. Students tracked into this program in elementary school would usually end up in honors and Advanced Placement classes in high school — classes necessary for gaining admission into prestigious colleges.

My parents, unfamiliar with our education system, didn’t understand any of this. But Ms. Weiland went out of her way to explain it to them. She also persuaded school administrators to test me for entrance into the program, and with her support, I eventually earned a spot.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Ms. Weiland’s persistence ultimately influenced my acceptance into Brown University. No matter how hard I worked or what grades I received, without gifted placement I could never have reached the academic classes necessary for an Ivy League school. Without that first opportunity given to me by Ms. Weiland, my entire educational trajectory would have changed.

The philosopher Seneca said, “Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.” But in the United States, too often people work hard every day, and yet never receive the opportunities that I did — an opportunity as simple as a teacher advocating on their behalf. Statistically, students of color remain consistently undiscovered by teachers who often , intentionally or not, choose mostly white, high-income students to enter advanced or “gifted” programs , regardless of their qualifications. Upon entering college, I met several students from across the country who also remained stuck within their education system until a teacher helped them find a way out.

Research has proved that these inconsistencies in opportunity exist in almost every aspect of American life. Your race can determine whether you interact with police, whether you are allowed to buy a house , and even whether your doctor believes you are really in pain . Your gender can determine whether you receive funding for your startup or whether your attempts at professional networking are effective. Your “foreign-sounding” name can determine whether someone considers you qualified for a job. Your family’s income can determine the quality of your public school or your odds that your entrepreneurial project succeeds .

These opportunities make a difference. They have created a society where most every American is working hard and yet only a small segment are actually moving forward. Knowing all this, I am no longer naive enough to believe the American dream is possible for everyone who attempts it. The United States doesn’t lack people trying. What it lacks is an equal playing field of opportunity.

2) Accomplishing the American dream can be socially alienating

Throughout my life, my family and I knew this uncomfortable truth: To better our future, we would have to enter spaces that felt culturally and racially unfamiliar to us. When I was 4 years old, my parents moved our family to a predominantly white part of town, so I could attend the county’s best public schools. I was often one of the only students of color in my gifted and honors programs. This trend continued in college and afterward: As an English major, I was often the only person of color in my literature and creative writing classes. As a teacher, I was often one of few teachers of color at my school or in my teacher training programs.

While attending Brown, a student of color once told me: “Our education is really just a part of our gradual ascension into whiteness.” At the time I didn’t want to believe him, but I came to understand what he meant: Often, the unexpected price for academic success is cultural abandonment.

In a piece for the New York Times , Vicki Madden described how education can create this “tug of war in [your] soul”:

To stay four years and graduate, students have to come to terms with the unspoken transaction: exchanging your old world for a new world, one that doesn’t seem to value where you came from. … I was keen to exchange my Western hardscrabble life for the chance to be a New York City middle-class museum-goer. I’ve paid a price in estrangement from my own people, but I was willing. Not every 18-year-old will make that same choice, especially when race is factored in as well as class.

So many times throughout my life, I’ve come home from classes, sleepovers, dinner parties, and happy hours feeling the heaviness of this exchange. I’ve had to Google cultural symbols I hadn’t understood in these conversations (What is “Harper’s”? What is “après-ski”?). At the same time, I remember using academia jargon my family couldn’t understand either. At a Christmas party, a friend called me out for using “those big Ivy League words” in a conversation. My parents had trouble understanding how independent my lifestyle had become and kept remarking on how much I had changed. Studying abroad, moving across the country for internships, living alone far away from family after graduating — these were not choices my Latin American parents had seen many women make.

An official from Brown told the Boston Globe that similar dynamics existed with many first-generation college students she worked with: “Often, [these students] come to college thinking that they want to return home to their communities. But an Ivy League education puts them in a different place — their language is different, their appearance is different, and they don’t fit in at home anymore, either.”

A Haitian-American friend of mine from college agreed: “After going to college, interacting with family members becomes a conflicted zone. Now you’re the Ivy League cousin who speaks a certain way, and does things others don’t understand. It changes the dynamic in your family entirely.”

A Latina friend of mine from Oakland felt this when she got accepted to the University of Southern California. She was the first person from her to family to leave home to attend college, and her conservative extended family criticized her for leaving home before marriage.

“One night they sat me down, told me my conduct was shameful and was staining the reputation of the family,” she told me, “My family thought a woman leaving home had more to do with her promiscuity than her desire for an education. They told me, ‘You’re just going to Los Angeles so you can have the freedom to be with whatever guy you want.’ When I think about what was most hard about college, it wasn’t the academics. It was dealing with my family’s disapproval of my life.”

We don’t acknowledge that too often, achievement in the United States means this gradual isolation from the people we love most. By simply striving toward American success, many feel forced to make to make that choice.

3) The American dream makes us focus single-mindedly on wealth and prestige

When I spoke to an Asian-American friend from college, he told me, “In the Asian New Jersey community I grew up in, I was surrounded by parents and friends whose mentality was to get high SAT scores, go to a top college, and major in medicine, law, or investment banking. No one thought outside these rigid tracks.” When he entered Brown, he followed these expectations by starting as a premed, then switching his major to economics.

This pattern is common in the Ivy League: Studies show that Ivy League graduates gravitate toward jobs with high salaries or prestige to justify the work and money we put into obtaining an elite degree. As a child of immigrants, there’s even more pressure to believe this is the only choice.

Of course, financial considerations are necessary for survival in our society. And it’s healthy to consider wealth and prestige when making life decisions, particularly for those who come from backgrounds with less privilege. But to what extent has this concern become an unhealthy obsession? For those who have the privilege of living a life based on a different set of values, to what extent has the American dream mindset limited our idea of success?

The Harvard Business Review reported that over time, people from past generations have begun to redefine success. As they got older, factors like “family happiness,” “relationships,” “balancing life and work,” and “community service” became more important than job titles and salaries. The report quoted a man in his 50s who said he used to define success as “becoming a highly paid CEO.” Now he defines it as “striking a balance between work and family and giving back to society.”

- Vox First Person: If ambition is ruining your life, you need to read Thoreau

While I spent high school and college focusing on achieving an Ivy League degree, and a prestigious job title afterward, I didn’t think about how other values mattered in my own notions of success. But after I took a “gap year” at 24 to travel, I realized that the way I’d defined the American dream was incomplete: It was not only about getting an education and a good job but also thinking about how my career choices contributed to my overall well-being. And it was about gaining experiences aside from my career, like travel . It was about making room for things like creativity, spirituality , and adventure when making important decisions in my life.

Courtney E. Martin addressed this in her TED talk called “The New Better Off,” where she said: “The biggest danger is not failing to achieve the American dream. The biggest danger is achieving a dream that you don’t actually believe in.”

Those realizations ultimately led me to pursue my current work as a travel writer. Whenever I have the privilege to do so, I attempt what Martin calls “the harder, more interesting thing”: to “compose a life where what you do every single day, the people you give your best love and ingenuity and energy to, aligns as closely as possible with what you believe.”

4) Even if you achieve the American dream, that doesn’t necessarily mean other Americans will accept you

A few years ago, I was working on my laptop in a hotel lobby, waiting for reception to process my booking. I wore leather boots, jeans, and a peacoat. A guest of the hotel approached me and began shouting in slow English (as if I couldn’t understand otherwise) that he needed me to clean his room. I was 25, had an Ivy League degree, and had completed one of the most competitive programs for college graduates in the country. And yet still I was being confused for the maid.

I realized then that no matter how hard I played by the rules, some people would never see me as a person of academic and professional success. This, perhaps, is the most psychologically disheartening part of the American dream: Achieving it doesn’t necessarily mean we can “transcend” racial stereotypes about who we are.

It just takes one look at the rhetoric by current politicians to know that as first-generation Americans, we are still not seen as “American” as others. As so many cases have illustrated recently, no matter how much we focus on proving them wrong, negative perceptions from others will continue to challenge our sense of self-worth.

For black immigrants or children of immigrants, this exclusionary messaging is even more obvious. Kari Mugo, a writer who immigrated to the US from Kenya when she was 18, expressed to me the disappointment she has felt trying to feel welcomed here: “It’s really hard to make an argument for a place that doesn’t want you, and shows that every single day. It’s been 12 years since I came here, and each year I’m growing more and more disillusioned.”

I still cherish my college years, and still feel immensely proud to call myself an Ivy League graduate. I am humbled by my parents’ sacrifices that allowed me to live the comparatively privileged life I’ve had. I acknowledge that it is in part because of this privilege that I can offer a critique of the United States in the first place. My parents and other immigrant families who focused only on survival didn’t have the luxury of being critical.

Yet having that luxury, I think it’s important to vocalize that in the United States, living the dream is far more nuanced than we often make others believe. As Mugo told me, “My friends back in Kenya always receive the message that America is so great. But I always wonder why we don’t ever tell the people back home what it’s really like. We always give off the illusion that everything is fine, without also acknowledging the many ways life here is really, really hard.”

I deeply respect the choices my parents made, and I’m deeply grateful for the opportunities the United States provided. But at this point in my family’s journey, I am curious to see what happens when we begin exploring a different dream.

Amanda Machado is a writer, editor, content strategist, and facilitator who works with publications and nonprofits around the world. You can learn more about her work at her website .

First Person is Vox’s home for compelling, provocative narrative essays. Do you have a story to share? Read our submission guidelines , and pitch us at [email protected] .

Most Popular

- Scientists just discovered a sea creature as large as two basketball courts. Here’s what it looks like.

- The real reason Mike Tyson is fighting Jake Paul

- What to buy before Trump makes everything more expensive Member Exclusive

- Could Trump actually get rid of the Department of Education?

- Trump is demanding an important change to the Senate confirmation process

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Criminal Justice

Gaetz is a reckless pick even by Trump’s standards.

Investors in private prisons think they’ve hit the jackpot with a second Trump presidency.

Turns out all of those indictments were pointless.

The backlash to criminal justice reform continues.

A mysterious Supreme Court case could change everything about criminal punishment.

How to Write a Standout College Essay about Immigrant Parents

Kate Sliunkova

AdmitYogi, Stanford MBA & MA in Education

If you're a high school student, chances are you've been asked to write an essay before. Writing about your immigrant parents can be a daunting task, but it can also be a beautiful opportunity to share your unique perspective. With the right strategies and mindset, you can craft an essay that not only showcases your writing skills but also honors the sacrifices and experiences of your immigrant parents.

Acknowledge the Significance of Your Parents' Journey

Before delving into writing your essay, it's crucial to acknowledge and appreciate the significance of your parents' immigration journey. Recognize the sacrifices they made, leaving behind their home country, family, and familiar surroundings, to provide a better life for you and your family. This appreciation will help you approach your essay with a deeper understanding and empathy. To explore successful college essays that highlight the importance of family sacrifices, visit AdmitYogi for inspiring examples.

Use Their Story as a Springboard for Self-Reflection

Your parents' immigration story serves as a powerful springboard for self-reflection. Reflect on the impact their journey has had on you - your identity, values, and aspirations. Consider how growing up in a multicultural household has shaped your worldview and influenced the choices you've made. This self-reflection allows you to connect your personal growth to your parents' experiences, providing a rich and compelling narrative. AdmitYogi can provide additional guidance on how to effectively incorporate self-reflection into your essay.

Choose a Meaningful Essay Topic

Selecting the right essay topic is crucial to capturing the attention of college admissions officers. Instead of focusing solely on your parents' story, choose a topic that reflects your own experiences and values, while weaving in elements of their journey. For example, you can explore moments where you grappled with language barriers and how those challenges fostered your determination to excel academically and embrace diverse perspectives.

Consider discussing the cultural differences you navigated while transitioning to the United States. Highlight the lessons you've learned about cultural diversity and your ability to adapt and thrive in new environments. This demonstrates your resilience and adaptability, qualities that colleges value in their applicants.

Infuse Your Essay with Personal Anecdotes

To make your essay engaging and memorable, infuse it with personal anecdotes that illustrate key moments or lessons from your own journey. Share specific stories that demonstrate your growth, resilience, and unique perspective. For instance, you can write about a time when you bridged a cultural gap between your parents' native traditions and American customs, showcasing your ability to navigate cultural complexities with sensitivity and openness.

By incorporating personal anecdotes, you showcase your individual experiences and emphasize how you have been shaped by your parents' immigration story, while maintaining the focus on you.

Reflect on the Intersection of Your Identity and Values

Colleges are interested in understanding who you are as an individual and the values you hold dear. Reflect on how your parents' immigration journey has influenced your own identity and values. Discuss the lessons you've learned about perseverance, determination, and the importance of education.

Highlight the ways in which your parents' sacrifices have motivated you to seize educational opportunities and strive for excellence. Emphasize how their story has instilled in you a deep appreciation for the value of education and the pursuit of knowledge.

Showcase Your Personal Growth and Aspirations

A compelling college essay should demonstrate personal growth and aspirations. Reflect on how your parents' experiences have influenced your own aspirations and goals for the future. Discuss the career paths, community involvement, or social initiatives that you are passionate about, and how they align with your values and the experiences you've had growing up as a child of immigrants.

Craft a Narrative That Captivates Admissions Officers

To make your essay truly standout, craft a narrative that captivates admissions officers. Start with a powerful and attention-grabbing opening. This could be a personal anecdote, a thought-provoking question, or a vivid description that draws the reader in from the very beginning.

Throughout your essay, use descriptive language and storytelling techniques to paint a vivid picture of your experiences and the impact of your parents' journey on your life. Engage the reader's senses and emotions, allowing them to connect with your story on a deeper level.

Writing a college application essay about your immigrant parents is an opportunity to celebrate your unique perspective and honor their experiences. By focusing on you and infusing your personal growth, values, and aspirations into the essay, you create a compelling narrative that highlights your individuality.

Remember to reflect on the intersection of your identity and values, choose a meaningful topic, and craft a narrative that captivates admissions officers. AdmitYogi , a trusted resource for successful college essays, offers a wealth of examples and guidance to help you throughout your writing journey. With these strategies and the support of AdmitYogi, you can write a standout essay that makes colleges eager to admit you and the incredible journey you represent.

Read applications

Read the essays, activities, and awards that got them in. Read one for free !

StanfordStudent

Stanford (+ 19 colleges)

Jaden Botros

Stanford (+ 22 colleges)

Anastasia Poliakova

Harvard (+ 12 colleges)

Related articles

Discover Extracurricular Activites at Columbia University

Dive into the dynamic world of Columbia University's extracurricular activities, where academia meets passion and individual growth is fostered beyond the classroom. This comprehensive guide uncovers the top extracurriculars at Columbia, featuring a myriad of clubs, organizations, and initiatives. Whether it's honing your leadership skills, engaging in community service, indulging in creative endeavors, or nurturing entrepreneurial ideas, there's a platform for everyone.

What Are the Admission Requirements for Harvard University?

Harvard University is the world’s most selective school. In this article, we discuss their admissions requirements and how you can meet them!

The Impact of Immigration on Families

- Posted June 1, 2022

- By Lory Hough

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Families and Community

- Immigration and Refugee Education

Research tells us that for young people growing up in immigrant families, their immigration status, and the status of their parents, has a big impact on their well-being. What research hasn’t really looked into, and what Ph.D. marshall Sarah Rendón García explored in her doctoral dissertation, is how young people actually learn about their (or their parents’) status.

As it turns out, there’s no one typical way.

“With the rise in the public’s engagement with immigration and anti-immigrant rhetoric, the messages children are receiving can come from home, school, or their neighborhood,” Rendón García says. “That's part of what my dissertation was trying to document, and my findings show there’s a spectrum of sources for children.”

Her own discovery happened when she was a teenager. Born in Venezuela to Colombian parents before moving to the United States, she was undocumented from the age of 9 to 21 but didn’t realize this until she tried to take part in a teenage rite-of-passage.

“I found out officially when it was time to get my driver’s license, and I wasn’t eligible because of my immigration status,” she says. “It was the first time I was told explicitly by my parents about our situation, but it wasn’t shocking because I had picked up on indicators of difference along the way as a child and adolescent. In other words, I had noticed things that made me and my family different from others based on our immigration status, like our inability to travel freely.”

Having a sense but not quite knowing the full story was a common theme Rendón García found while doing her research, which focused on interviews with children from ages 7 to 15 who live in mixed-status families — meaning at least one parent or caregiver is undocumented.

“The majority of the children I talked to showed evidence of being, at the very least, familiar with the topic of immigration status,” she says. It was their parents and caretakers who weren’t always ready to talk.

“Most parents with whom I spoke wouldn’t have chosen to have conversations with their children about immigration status just yet,” she says. “A big challenge for parents was being forced into these conversations because of the questions their children were asking or the things their children were noticing. It’s hard for adults to be thrown into such a delicate conversation with children who have varying cognitive capacities to employ in order to understand what is being explained. Immigration policy is complicated to the point that it’s already challenging for adults to grapple with their understanding, let alone how to explain it to a child.”

Parents also want to shield their children.

“They want to protect their children from the potential implications of such life-changing information,” she says. “Parents spoke about the challenges of deciding whether to tell their children the truth about being undocumented and the potential threat of family separation so that their children wouldn’t be caught surprised if their parents were detained and/or deported, or to protect them from the truth so that children didn’t experience anxiety or stress about something that might not happen.”

Rendón García knows first-hand about that anxiety and stress.

“I was undocumented during a time where public awareness was not yet where it is now. That meant the biggest impact of my immigration status on my experience was psychological," she says. “I didn’t always feel understood by my educators, even when they had the best intentions, and I didn't feel safe to share my experience with them. This is why I gravitated to the social-emotional development and psychological well-being of mixed-status immigrant families in my professional and academic work. My goal is to contribute knowledge that helps practitioners, policymakers, and researchers move toward creating safer spaces for this population.”

She first started down this path as a master’s student but always with an eye toward joining the Ph.D. Program.

“I saw there was not a lot of research out there about people like me,” she says. The Ed School also helped her approach her work from an interdisciplinary lens.

“This allowed me to think creatively about the questions I was asking and the methods I was using to answer those questions," she says. “I've been able to bring together psychology, sociology, education, and immigration studies to better understand the experiences of mixed-status families. Most importantly, I think HGSE has instilled certain priorities in me regarding the impact I want my work to have.”

After graduation, Rendón García will continue at the Ed School as a Dean’s Postdoctoral Fellow, working with professor-in-residence Carola Suarez-Orozco on the Immigration Initiative at Harvard , teaching for the How People Learn course, and conducting a National Science Foundation-funded intervention research project for parents in mixed-status families as they prepare to engage in immigration socialization.

Asked if anything surprised her along the way while doing her research, she says it’s a tough question to answer, in part because of the families she came to know.

“It was really difficult to see children grappling with the threat of family separation and adults grappling with the impossible decision of protecting their children in the short-term vs. the long-term,” she says. “That wasn’t necessarily surprising because I had anecdotal stories of it happening, but it was still upsetting to see the evidence across and within families.”

The latest research, perspectives, and highlights from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Exploring the Effects of Desegregation

Lost in Translation

New comparative study from Ph.D. candidate Maya Alkateb-Chami finds strong correlation between low literacy outcomes for children and schools teaching in different language from home

Exclusive curated boxes up to 82% off — plus deals on Yankee Candle, more

- Black Friday

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

- TODAY Plaza

‘So, are you an alien?’ What it was like to grow up as an undocumented immigrant

TODAY is editorially independent. When you buy through our links, we may earn a commission. Learn more .

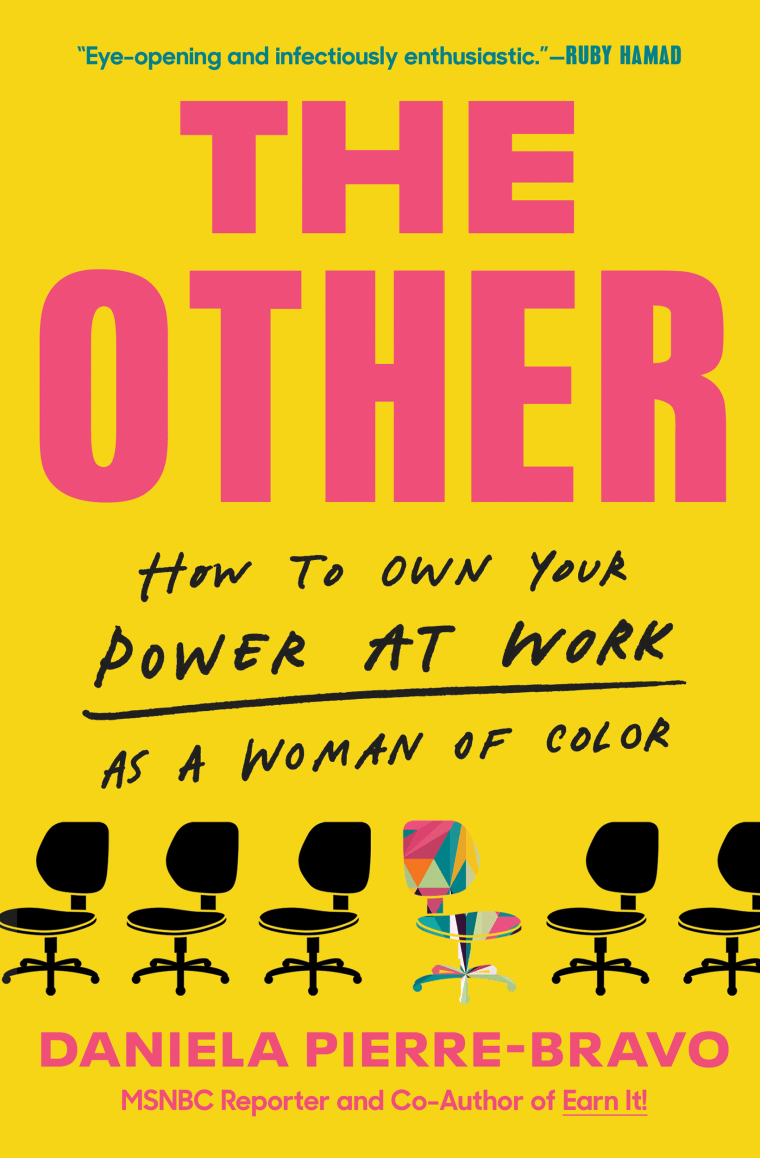

Daniela Pierre-Bravo is a bestselling author, speaker and MSNBC reporter for “Morning Joe.” In her new book, “The Other: How to Own Your Power at Work as a Woman of Color,” she shares her personal story about being an undocumented immigrant from Chile and how she rose through the ranks in her career. This is an excerpt of the book, which came out Aug. 23.

Growing up, I did not belong. Not on paper, not in the system and not in my environment.

The word “undocumented” is more than a status; it’s a feeling. It’s a constant state of being, and it was always there with me. Am I enough? Am I worthy? I was not alone in this feeling, but in my case, there was supporting evidence that made it harder not to take those thoughts as factual. I lacked the very paperwork that validated my belonging in this country. I was in total limbo without a path forward. Whatever inadequacies I felt were compounded by my lack of status. So I built up a shell to protect me from the prejudice I encountered in my small town, and I learned to bury my voice — to accommodate, explain and appease. It was a coping mechanism that I absorbed early on, which quickly spilled over into areas of my life where I felt like I had to work hard to prove myself.

One of these experiences that stayed with me was when I met my then-boyfriend’s parents as a teen. No matter who you are, meeting a partner’s parents for the first time can be nerve-racking. I wanted to do my best to make a good first impression for many reasons. He had a big, close-knit family like mine, but his upbringing was vastly different from my own. He had grown up in the same town all his life and had conservative, well-educated parents who had gone to top-ranked schools. They were well off and well known in town, the sort of parents who were at every one of their kids’ games and recitals, and could comfortably clock out of their nine-to-five jobs to enjoy family meals. This was a stark contrast to my immigrant parents, who worked two or three shifts and came home, on a good day, by eight at night with a bucket of Lee’s chicken, which each kid would eat on their own schedule because our parents were too exhausted to impose rules about family mealtimes.

I was scheduled to meet my boyfriend’s family for dinner at one of the best restaurants in town. Blood rushed to my cheeks as my family dropped me off in our station wagon. I was late. My dad had fallen behind schedule, struggling to start the car engine on his way home from his factory job across town.

“Here is fine!” I blurted before we neared the restaurant’s front door, my mind swirling with the thought that this was the first impression I’d have to lead with.

“Good luck!” yelled my 12-year-old brother from the back seat through a devilish grin and a big cackle. Even at his age, he knew I was walking into a minefield. I rolled my eyes and hoped the loud creak of the old car door closing couldn’t be heard inside.

As I stepped into the Italian restaurant, I quickly spotted my boyfriend and his whole family on the left, already sitting at the table, and watched as all of their eyes turned my way. I walked toward them knowing I would be vetted, almost expecting that they already had some sort of preconceived judgment about my immigrant roots, but I figured if I played my cards right, they’d overlook the cultural and socioeconomic gaps between us.

I (expected) that they already had some sort of preconceived judgment about my immigrant roots, but I figured if I played my cards right, they’d overlook the cultural and socioeconomic gaps between us.

After apologizing profusely for being late, I took my seat and exchanged small talk over appetizers. With the main course, lasagna, came the usual softballs: “How is school going?” “What was it like growing up in Chile?” And I was batting like a champ, or so I thought. Until his mother threw the ultimate curveball.

“So, are you an alien? I mean ... do you have a green card?” Her eyes were locked on me as she fumbled through this question. And for an instant, I stopped breathing. The inquisition hit me like a pile of rocks. My thoughts reeled. What do I say? How can I answer this and still be in her good graces? Will they accept me if I tell them the truth?

“Well — I ... ”

I felt totally blindsided.

“Oh my God, Mom! No, she’s an illegal alien!” offered one of my boyfriend’s brothers sarcastically, as if coming to my rescue.

“What a question!” followed his father, as everyone joined in and laughed it all off, delighting themselves in the bluntness of the question that so obviously did not need to be answered.

As I smiled along with them, playing into their assumption that I was not undocumented, a strange out-of-body sensation came over me, as if I were two separate people digesting my environment. The confident version of me pretended that this outright biased comment had little to no effect on the expertly disguised other version of me, who was screaming at me in my mind to run away before I got caught.

When I came back from what felt like a mental blackout, I found the confident person in me take over. Keep calm. I explained my immigration status by lying to appease them, telling them that my paperwork was in process or something. I fought every inch of my gut and soul from disclosing the truth. As I scrambled to find a way to ease their doubts about my legal status, I was unintentionally feeding into their bias and also internalizing it. It was one of the first times I remember feeling deep shame. Even so, I self-soothed, conditioning my body and words to deflect this uncomfortable feeling of inadequacy, and carried on.

In my mind, my boyfriend’s mother’s message was clear: You don’t belong. It felt like she had already made up her mind before even taking the chance to get to know me. I’m sure you can relate on some level, especially if, like me, you grew up in a community where you stuck out like a sore thumb. I began to believe that I needed to adapt by appeasing whatever doubts, worries or hesitancies might come up about me and my background. After all, these were good, community-and family-oriented, churchgoing people. It must not be them, I told myself. It’s me. I needed to work harder to assimilate and earn their trust.

This uncomfortable dinner situation was the first time I felt the threat of what being “the other” meant to a group in which family, friends and acquaintances, for the most part, all looked the same. Those hegemonic communities have grown used to the consistency that comes from the lack of diversity within their close circles. I can imagine people’s skin crawled in my town at the thought that I might be “illegal,” but I needed more years to process and fully understand how their bias likely came from simple lack of exposure to someone different from them.

Of course people are unfamiliar with things they haven’t encountered before, but to wholeheartedly judge, dismiss or reject, well, that’s bias in a nutshell, if not outright bigotry. It’s the fear of the unknown. It may have helped ease my stress if I had understood this back then, but all I knew was that I was the odd one out, someone they couldn’t quite put their finger on, and deep down inside, that dissonance probably scared them. This made me harbor shame about my very identity. I didn’t have anyone like me in my corner to encourage me or teach me how to handle that emotion. My family was likely dealing with their own repressed emotions, and were also much too worried about getting food on our table to think about feelings .

That relationship was short-lived (shocker, I know). But this memory remained in my subconscious for years, rearing its ugly head on other occasions where I faced my socioeconomic limits when trying to make it into rooms where I felt like I didn’t belong. You are illegal! it yelled at me, making me feel like a total fraud.

What I didn’t know back then was that I was not “illegal”; I was undocumented. I also didn’t know that calling me or anyone in my circumstance an “alien” carried an enormous psychological weight. Currently, there is legislation introduced in Congress that would remove the word “alien” from U.S. immigration laws and replace it with “noncitizen.” Immigration activists, legal scholars and others have taken issue with the term “alien,” saying it downplays the importance of the role immigrants have had historically in the United States, from the European immigrants who colonized it to the enslaved Africans who were forced to immigrate against their will. However you want to look at it, the term holds one unchallengeable message for those on the receiving end: that we are foreign, outsiders, other . We feel the force of its psychological weight. That one measly word dangled over us has the power to make us question ourselves, our identities and our place in the world. This epithet translates into a rejection that tells us that our inherent being is not good enough, is not worthy, does not and will never belong. We exist “illegally” in places where we contribute, build communities, volunteer in religious spaces and pay taxes for welfare and health care that we ourselves cannot use. “Illegals” like us shouldn’t exist ... yet we do.

Excerpted from “The Other: How to Own Your Power at Work as a Woman of Color” by Daniela Pierre-Bravo. Copyright © 2022 by Daniela Pierre-Bravo. Reprinted with permission of Legacy Lit. All rights reserved.

Daniela Pierre-Bravo is a bestselling author, speaker and MSNBC reporter for "Morning Joe." She is a contributor and producer for NBC’s “Know Your Value” platform, coauthor of "Earn It!" and most recently the author of her first solo book “The Other,” which came out in August 2022. A former Cosmopolitan magazine columnist, Pierre-Bravo has written on career advice, mental health and financial wellness with an emphasis on women of color.

I’m 69 and single. ‘The Golden Bachelorette’ might inspire me to start dating again

‘Betty La Fea’ helped me find confidence as a young girl. What will she do now?

Dear Shannen Doherty: I’m sorry I bought the ‘I Hate Brenda’ newsletter in high school

After Luke Perry, Shannen Doherty’s death is even more devastating for fans

As an Asian American child, ‘Mulan’ was my favorite movie. Here’s how it held up rewatching as an adult

Why I’m not holding back about what happened to me after I was on ‘The Bachelor’

I got my hands on a coveted, sold-out 'DunKings' suit. Here's what happened next

‘Quiet on Set’ made me feel guilty for the role I played in ’90s pop culture

‘Summer House’ star Carl Radke: Watching myself on reality TV helped me get sober

Author Jo Piazza: How a 100-year-old family murder mystery inspired my new novel

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Rosemary Santos shares how her parents’ sacrifices have pushed her to become a high achiever in search of a different life path. Growing up in a first-generation immigrant family, I witnessed my parents’ hard work ethic and challenging traditional Mexican customs.

In this essay, I will delve into the struggles faced by individuals like me having immigrant parents. From language barriers to cultural clashes, these struggles can shape our identities, values, and perspectives in profound ways.

In this post, we will discuss some of the challenges of having immigrant parents, including the ones that are often tabooed. 1. The Heaviness of Unspoken Guilt. Children naturally blame...

This essay will delve into the experiences of immigrant parents, exploring the sacrifices they make, the obstacles they overcome, and the impact they have on their children's lives. By examining the stories of immigrant parents from diverse backgrounds, we will uncover the resilience, determination, and love that drive them to create a better ...

In this essay, I will explore the profound impact of having immigrant parents on my upbringing and perspective. Growing up, I had the unique opportunity to bridge the gap between my life in the United States and the experiences of my parents in Belarus, a country with its own set of challenges and hardships. These contrasting worlds have shaped ...

Being an Immigrant American by Malia E., Royal Oak High School, Michigan. Summary: This writing piece is about how first generation immigrants view living in America, versus second generation immigrants and some of the struggles they go through to really feel American.

Studying abroad, moving across the country for internships, living alone far away from family after graduating — these were not choices my Latin American parents had seen many women make.

Discover how to write a standout college application essay that focuses on your personal growth and values while celebrating your immigrant parents' journey. Explore strategies to infuse your own unique perspective into the essay and learn from examples of successful essays at AdmitYogi.

Research tells us that for young people growing up in immigrant families, their immigration status, and the status of their parents, has a big impact on their well-being.

Essay. ‘So, are you an alien?’. What it was like to grow up as an undocumented immigrant. As a teenager, I internalized the bias that surrounded me in my American town. In Daniela...