Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

My Successful Harvard Application (Complete Common App + Supplement)

Other High School , College Admissions , Letters of Recommendation , Extracurriculars , College Essays

In 2005, I applied to college and got into every school I applied to, including Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and MIT. I decided to attend Harvard.

In this guide, I'll show you the entire college application that got me into Harvard—page by page, word for word .

In my complete analysis, I'll take you through my Common Application, Harvard supplemental application, personal statements and essays, extracurricular activities, teachers' letters of recommendation, counselor recommendation, complete high school transcript, and more. I'll also give you in-depth commentary on every part of my application.

To my knowledge, a college application analysis like this has never been done before . This is the application guide I wished I had when I was in high school.

If you're applying to top schools like the Ivy Leagues, you'll see firsthand what a successful application to Harvard and Princeton looks like. You'll learn the strategies I used to build a compelling application. You'll see what items were critical in getting me admitted, and what didn't end up helping much at all.

Reading this guide from beginning to end will be well worth your time—you might completely change your college application strategy as a result.

First Things First

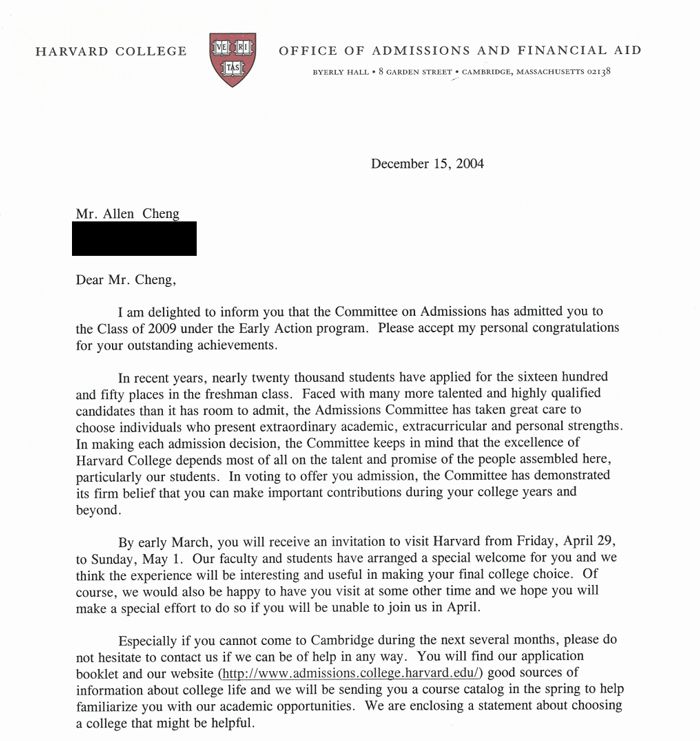

Here's the letter offering me admission into Harvard College under Early Action.

I was so thrilled when I got this letter. It validated many years of hard work, and I was excited to take my next step into college (...and work even harder).

I received similar successful letters from every college I applied to: Princeton, Stanford, and MIT. (After getting into Harvard early, I decided not to apply to Yale, Columbia, UChicago, UPenn, and other Ivy League-level schools, since I already knew I would rather go to Harvard.)

The application that got me admitted everywhere is the subject of this guide. You're going to see everything that the admissions officers saw.

If you're hoping to see an acceptance letter like this in your academic future, I highly recommend you read this entire article. I'll start first with an introduction to this guide and important disclaimers. Then I'll share the #1 question you need to be thinking about as you construct your application. Finally, we'll spend a lot of time going through every page of my college application, both the Common App and the Harvard Supplemental App.

Important Note: the foundational principles of my application are explored in detail in my How to Get Into Harvard guide . In this popular guide, I explain:

- what top schools like the Ivy League are looking for

- how to be truly distinctive among thousands of applicants

- why being well-rounded is the kiss of death

If you have the time and are committed to maximizing your college application success, I recommend you read through my Harvard guide first, then come back to this one.

You might also be interested in my other two major guides:

- How to Get a Perfect SAT Score / Perfect ACT Score

- How to Get a 4.0 GPA

What's in This Harvard Application Guide?

From my student records, I was able to retrieve the COMPLETE original application I submitted to Harvard. Page by page, word for word, you'll see everything exactly as I presented it : extracurricular activities, awards and honors, personal statements and essays, and more.

In addition to all this detail, there are two special parts of this college application breakdown that I haven't seen anywhere else :

- You'll see my FULL recommendation letters and evaluation forms. This includes recommendations from two teachers, one principal, and supplementary writers. Normally you don't get to see these letters because you waive access to them when applying. You'll see how effective strong teacher advocates will be to your college application, and why it's so important to build strong relationships with your letter writers .

- You'll see the exact pen marks made by my Harvard admissions reader on my application . Members of admissions committees consider thousands of applications every year, which means they highlight the pieces of each application they find noteworthy. You'll see what the admissions officer considered important—and what she didn't.

For every piece of my application, I'll provide commentary on what made it so effective and my strategies behind creating it. You'll learn what it takes to build a compelling overall application.

Importantly, even though my application was strong, it wasn't perfect. I'll point out mistakes I made that I could have corrected to build an even stronger application.

Here's a complete table of contents for what we'll be covering. Each link goes directly to that section, although I'd recommend you read this from beginning to end on your first go.

Common Application

Personal Data

Educational data, test information.

- Activities: Extracurricular, Personal, Volunteer

- Short Answer

- Additional Information

Academic Honors

Personal statement, teacher and counselor recommendations.

- Teacher Letter #1: AP Chemistry

- Teacher Letter #2: AP English Lang

School Report

- Principal Recommendation

Harvard Application Supplement

- Supplement Form

- Writing Supplement Essay

Supplementary Recommendation #1

Supplementary recommendation #2, supplemental application materials.

Final Advice for You

I mean it—you'll see literally everything in my application.

In revealing my teenage self, some parts of my application will be pretty embarrassing (you'll see why below). But my mission through my company PrepScholar is to give the world the most helpful resources possible, so I'm publishing it.

One last thing before we dive in—I'm going to anticipate some common concerns beforehand and talk through important disclaimers so that you'll get the most out of this guide.

Important Disclaimers

My biggest caveat for you when reading this guide: thousands of students get into Harvard and Ivy League schools every year. This guide tells a story about one person and presents one archetype of a strong applicant. As you'll see, I had a huge academic focus, especially in science ( this was my Spike ). I'm also irreverent and have a strong, direct personality.

What you see in this guide is NOT what YOU need to do to get into Harvard , especially if you don't match my interests and personality at all.

As I explain in my Harvard guide , I believe I fit into one archetype of a strong applicant—the "academic superstar" (humor me for a second, I know calling myself this sounds obnoxious). There are other distinct ways to impress, like:

- being world-class in a non-academic talent

- achieving something difficult and noteworthy—building a meaningful organization, writing a novel

- coming from tremendous adversity and performing remarkably well relative to expectations

Therefore, DON'T worry about copying my approach one-for-one . Don't worry if you're taking a different number of AP courses or have lower test scores or do different extracurriculars or write totally different personal statements. This is what schools like Stanford and Yale want to see—a diversity in the student population!

The point of this guide is to use my application as a vehicle to discuss what top colleges are looking for in strong applicants. Even though the specific details of what you'll do are different from what I did, the principles are the same. What makes a candidate truly stand out is the same, at a high level. What makes for a super strong recommendation letter is the same. The strategies on how to build a cohesive, compelling application are the same.

There's a final reason you shouldn't worry about replicating my work—the application game has probably changed quite a bit since 2005. Technology is much more pervasive, the social issues teens care about are different, the extracurricular activities that are truly noteworthy have probably gotten even more advanced. What I did might not be as impressive as it used to be. So focus on my general points, not the specifics, and think about how you can take what you learn here to achieve something even greater than I ever did.

With that major caveat aside, here are a string of smaller disclaimers.

I'm going to present my application factually and be 100% straightforward about what I achieved and what I believed was strong in my application. This is what I believe will be most helpful for you. I hope you don't misinterpret this as bragging about my accomplishments. I'm here to show you what it took for me to get into Harvard and other Ivy League schools, not to ask for your admiration. So if you read this guide and are tempted to dismiss my advice because you think I'm boasting, take a step back and focus on the big picture—how you'll improve yourself.

This guide is geared toward admissions into the top colleges in the country , often with admissions rates below 10%. A sample list of schools that fit into this: Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Stanford, Columbia, MIT, UChicago, Duke, UPenn, CalTech, Johns Hopkins, Dartmouth, Northwestern, Brown. The top 3-5 in that list are especially looking for the absolute best students in the country , since they have the pick of the litter.

Admissions for these selective schools works differently from schools with >20% rates. For less selective schools, having an overall strong, well-rounded application is sufficient for getting in. In particular, having an above average GPA and test scores goes the majority of the way toward getting you admission to those schools. The higher the admission rate, the more emphasis will be placed on your scores. The other pieces I'll present below—personal statements, extracurriculars, recommendations—will matter less.

Still, it doesn't hurt to aim for a stronger application. To state the obvious, an application strong enough to get you Columbia will get you into UCLA handily.

In my application, I've redacted pieces of my application for privacy reasons, and one supplementary recommendation letter at the request of the letter writer. Everything else is unaltered.

Throughout my application, we can see marks made by the admissions officer highlighting and circling things of note (you'll see the first example on the very first page). I don't have any other applications to compare these to, so I'm going to interpret these marks as best I can. For the most part, I assume that whatever he underlines or circles is especially important and noteworthy —points that he'll bring up later in committee discussions. It could also be that the reader got bored and just started highlighting things, but I doubt this.

Finally, I co-founded and run a company called PrepScholar . We create online SAT/ACT prep programs that adapt to you and your strengths and weaknesses . I believe we've created the best prep program available, and if you feel you need to raise your SAT/ACT score, then I encourage you to check us out . I want to emphasize that you do NOT need to buy a prep program to get a great score , and the advice in this guide has little to do with my company. But if you're aren't sure how to improve your score and agree with our unique approach to SAT/ACT prep, our program may be perfect for you.

With all this past us, let's get started.

The #1 Most Important College Application Question: What Is Your PERSONAL NARRATIVE?

If you stepped into an elevator with Yale's Dean of Admissions and you had ten seconds to describe yourself and why you're interesting, what would you say?

This is what I call your PERSONAL NARRATIVE. These are the three main points that represent who you are and what you're about . This is the story that you tell through your application, over and over again. This is how an admissions officer should understand you after just glancing through your application. This is how your admissions officer will present you to the admissions committee to advocate for why they should accept you.

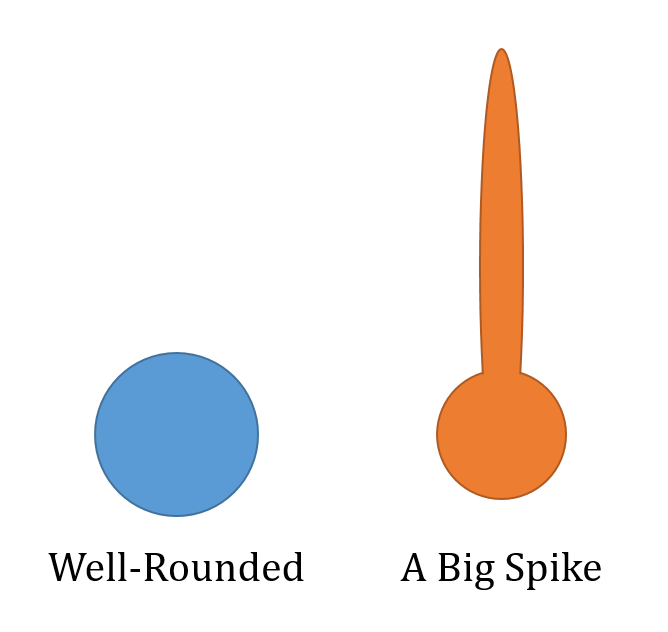

The more unique and noteworthy your Personal Narrative is, the better. This is how you'll stand apart from the tens of thousands of other applicants to your top choice school. This is why I recommend so strongly that you develop a Spike to show deep interest and achievement. A compelling Spike is the core of your Personal Narrative.

Well-rounded applications do NOT form compelling Personal Narratives, because "I'm a well-rounded person who's decent at everything" is the exact same thing every other well-rounded person tries to say.

Everything in your application should support your Personal Narrative , from your course selection and extracurricular activities to your personal statements and recommendation letters. You are a movie director, and your application is your way to tell a compelling, cohesive story through supporting evidence.

Yes, this is overly simplistic and reductionist. It does not represent all your complexities and your 17 years of existence. But admissions offices don't have the time to understand this for all their applicants. Your PERSONAL NARRATIVE is what they will latch onto.

Here's what I would consider my Personal Narrative (humor me since I'm peacocking here):

1) A science obsessive with years of serious research work and ranked 6 th in a national science competition, with future goals of being a neuroscientist or physician

2) Balanced by strong academic performance in all subjects (4.0 GPA and perfect test scores, in both humanities and science) and proficiency in violin

3) An irreverent personality who doesn't take life too seriously, embraces controversy, and says what's on his mind

These three elements were the core to my application. Together they tell a relatively unique Personal Narrative that distinguishes me from many other strong applicants. You get a surprisingly clear picture of what I'm about. There's no question that my work in science was my "Spike" and was the strongest piece of my application, but my Personal Narrative included other supporting elements, especially a description of my personality.

My College Application, at a High Level

Drilling down into more details, here's an overview of my application.

- This put me comfortably in the 99 th percentile in the country, but it was NOT sufficient to get me into Harvard by itself ! Because there are roughly 4 million high school students per year, the top 1 percentile still has 40,000 students. You need other ways to set yourself apart.

- Your Spike will most often come from your extracurriculars and academic honors, just because it's hard to really set yourself apart with your coursework and test scores.

- My letters of recommendation were very strong. Both my recommending teachers marked me as "one of the best they'd ever taught." Importantly, they corroborated my Personal Narrative, especially regarding my personality. You'll see how below.

- My personal statements were, in retrospect, just satisfactory. They represented my humorous and irreverent side well, but they come across as too self-satisfied. Because of my Spike, I don't think my essays were as important to my application.

Finally, let's get started by digging into the very first pages of my Common Application.

There are a few notable points about how simple questions can actually help build a first impression around what your Personal Narrative is.

First, notice the circle around my email address. This is the first of many marks the admissions officer made on my application. The reason I think he circled this was that the email address I used is a joke pun on my name . I knew it was risky to use this vs something like [email protected], but I thought it showed my personality better (remember point #3 about having an irreverent personality in my Personal Narrative).

Don't be afraid to show who you really are, rather than your perception of what they want. What you think UChicago or Stanford wants is probably VERY wrong, because of how little information you have, both as an 18-year-old and as someone who hasn't read thousands of applications.

(It's also entirely possible that it's a formality to circle email addresses, so I don't want to read too much into it, but I think I'm right.)

Second, I knew in high school that I wanted to go into the medical sciences, either as a physician or as a scientist. I was also really into studying the brain. So I listed both in my Common App to build onto my Personal Narrative.

In the long run, both predictions turned out to be wrong. After college, I did go to Harvard Medical School for the MD/PhD program for 4 years, but I left to pursue entrepreneurship and co-founded PrepScholar . Moreover, in the time I did actually do research, I switched interests from neuroscience to bioengineering/biotech.

Colleges don't expect you to stick to career goals you stated at the age of 18. Figuring out what you want to do is the point of college! But this doesn't give you an excuse to avoid showing a preference. This early question is still a chance to build that Personal Narrative.

Thus, I recommend AGAINST "Undecided" as an area of study —it suggests a lack of flavor and is hard to build a compelling story around. From your high school work thus far, you should at least be leaning to something, even if that's likely to change in the future.

Finally, in the demographic section there is a big red A, possibly for Asian American. I'm not going to read too much into this. If you're a notable minority, this is where you'd indicate it.

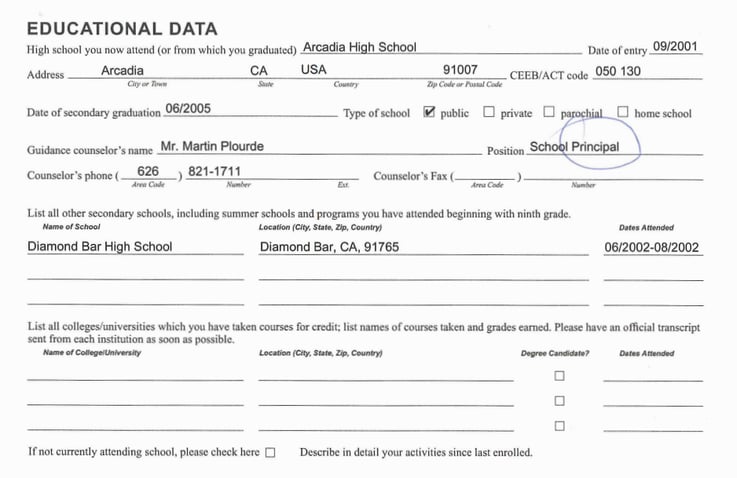

Now known as: Education

This section was straightforward for me. I didn't take college courses, and I took a summer chemistry class at a nearby high school because I didn't get into the lottery at my school that year (I refer to this briefly in my 4.0 GPA guide ).

The most notable point of this section: the admissions officer circled Principal here . This is notable because our school Principal only wrote letters for fewer than 10 students each year. Counselors wrote letters for the other hundreds of students in my class, which made my application stand out just a little.

I'll talk more about this below, when I share the Principal's recommendation.

(In the current Common Application, the Education section also includes Grades, Courses, and Honors. We'll be covering each of those below).

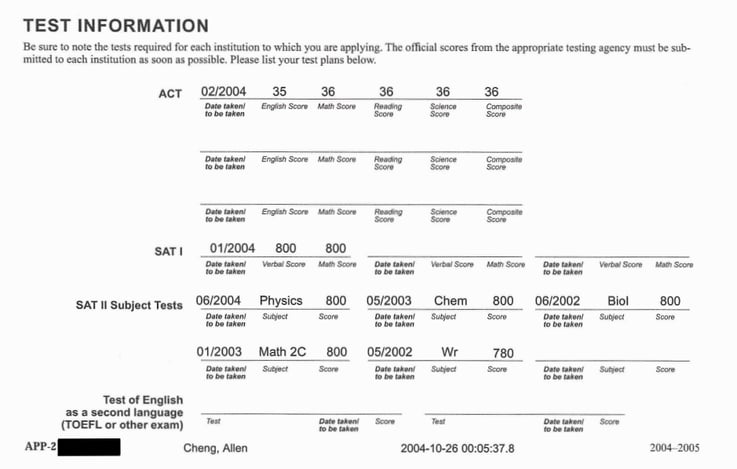

Now known as: Testing

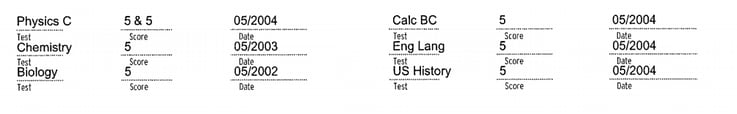

Back then AP scores weren't part of this section, but I'll take them from another part of my application here.

However, their standards are still very high. You really do want to be in that top 1 percentile to pass the filter. A 1400 on the SAT IS going to put you at a disadvantage because there are so many students scoring higher than you. You'll really have to dig yourself out of the hole with an amazing application.

I talk about this a lot more in my Get into Harvard guide (sorry to keep linking this, but I really do think it's an important guide for you to read).

Let's end this section with some personal notes.

Even though math and science were easy for me, I had to put in serious effort to get an 800 on the Reading section of the SAT . As much as I wish I could say it was trivial for me, it wasn't. I learned a bunch of strategies and dissected the test to get to a point where I understood the test super well and reliably earned perfect scores.

I cover the most important points in my How to Get a Perfect SAT Score guide , as well as my 800 Guides for Reading , Writing , and Math .

Between the SAT and ACT, the SAT was my primary focus, but I decided to take the ACT for fun. The tests were so similar that I scored a 36 Composite without much studying. Having two test scores is completely unnecessary —you get pretty much zero additional credit. Again, with one test score, you have already passed their filter.

Finally, class finals or state-required exams are a breeze if you get a 5 on the corresponding AP tests .

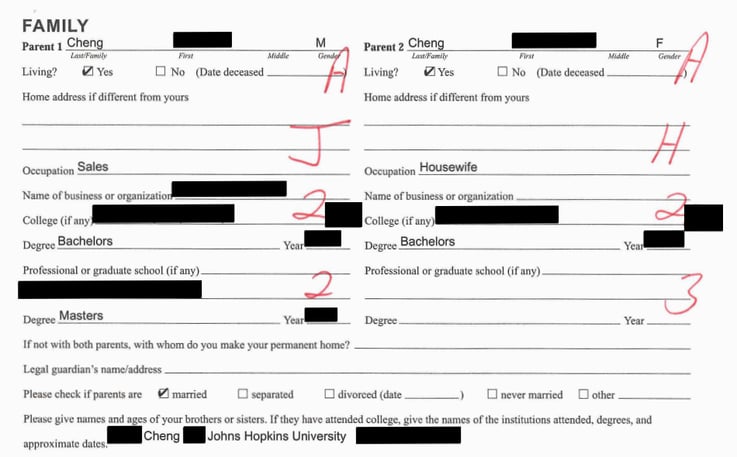

Now known as: Family (still)

This section asks for your parent information and family situation. There's not much you can do here besides report the facts.

I'm redacting a lot of stuff again for privacy reasons.

The reader made a number of marks here for occupation and education. There's likely a standard code for different types of occupations and schools.

If I were to guess, I'd say that the numbers add to form some metric of "family prestige." My dad got a Master's at a middle-tier American school, but my mom didn't go to graduate school, and these sections were marked 2 and 3, respectively. So it seems higher numbers are given for less prestigious educations by your parents. I'd expect that if both my parents went to schools like Caltech and Dartmouth, there would be even lower numbers here.

This makes me think that the less prepared your family is, the more points you get, and this might give your application an extra boost. If you were the first one in your family to go to college, for example, you'd be excused for having lower test scores and fewer AP classes. Schools really do care about your background and how you performed relative to expectations.

In the end, schools like Harvard say pretty adamantly they don't use formulas to determine admissions decisions, so I wouldn't read too much into this. But this can be shorthand to help orient an applicant's family background.

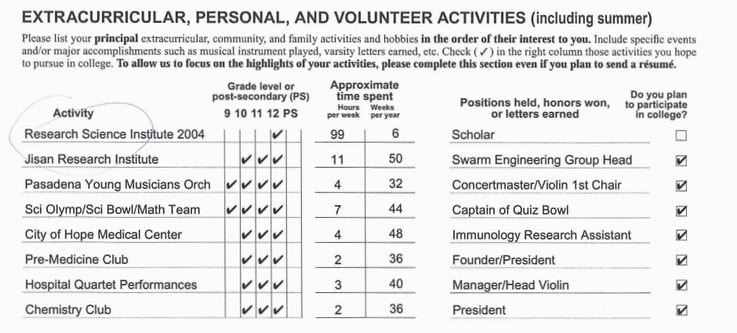

Extracurricular, Personal, and Volunteer Activities

Now known as: Activities

For most applicants, your Extracurriculars and your Academic Honors will be where you develop your Spike and where your Personal Narrative shines through. This was how my application worked.

Just below I'll describe the activities in more detail, but first I want to reflect on this list.

As instructed, my extracurriculars were listed in the order of their interest to me. The current Common App doesn't seem to ask for this, but I would still recommend it to focus your reader's attention.

The most important point I have to make about my extracurriculars: as you go down the list, there is a HUGE drop in the importance of each additional activity to the overall application. If I were to guess, I assign the following weights to how much each activity contributed to the strength of my activities section:

In other words, participating in the Research Science Institute (RSI) was far more important than all of my other extracurriculars, combined. You can see that this was the only activity my admissions reader circled.

You can see how Spike-y this is. The RSI just completely dominates all my other activities.

The reason for this is the prestige of RSI. As I noted earlier, RSI was (and likely still is) the most prestigious research program for high school students in the country, with an admission rate of less than 5% . Because the program was so prestigious and selective, getting in served as a big confirmation signal of my academic quality.

In other words, the Harvard admissions reader would likely think, "OK, if this very selective program has already validated Allen as a top student, I'm inclined to believe that Allen is a top student and should pay special attention to him."

Now, it took a lot of prior work to even get into RSI because it's so selective. I had already ranked nationally in the Chemistry Olympiad (more below), and I had done a lot of prior research work in computer science (at Jisan Research Institute—more about this later). But getting into RSI really propelled my application to another level.

Because RSI was so important and was such a big Spike, all my other extracurriculars paled in importance. The admissions officer at Princeton or MIT probably didn't care at all that I volunteered at a hospital or founded a high school club .

This is a good sign of developing a strong Spike. You want to do something so important that everything else you do pales in comparison to it. A strong Spike becomes impossible to ignore.

In contrast, if you're well-rounded, all your activities hold equal weight—which likely means none of them are really that impressive (unless you're a combination of Olympic athlete, internationally-ranked science researcher, and New York Times bestselling author, but then I'd call you unicorn because you don't exist).

Apply this concept to your own interests—what can be so impressive and such a big Spike that it completely overshadows all your other achievements?

This might be worth spending a disproportionate amount of time on. As I recommend in my Harvard guide and 4.0 GPA guide , smartly allocating your time is critical to your high school strategy.

In retrospect, one "mistake" I made was spending a lot of time on the violin. Each week I spent eight hours on practice and a lesson and four hours of orchestra rehearsals. This amounted to over 1,500 hours from freshman to junior year.

The result? I was pretty good, but definitely nowhere near world-class. Remember, there are thousands of orchestras and bands in the country, each with their own concertmasters, drum majors, and section 1 st chairs.

If I were to optimize purely for college applications, I should have spent that time on pushing my spike even further —working on more Olympiad competitions, or doing even more hardcore research.

Looking back I don't mind this much because I generally enjoyed my musical training and had a mostly fun time in orchestra (and I had a strong Spike anyway). But this problem can be a lot worse for well-rounded students who are stretched too thin.

Aside from these considerations about a Spike, I have two major caveats.

First, developing a Spike requires continuous, increasingly ambitious foundational work. It's like climbing a staircase. From the beginning of high school, each step was more and more ambitious—my first academic team, my first research experience, leading up to state and national competitions and more serious research work.

So when I suggest devoting a lot of time to developing your Spike, it's not necessarily the Spike in itself—it's also spending time on foundational work leading up to what will be your major achievement. That's why I don't see my time with academic teams or volunteering as wasted, even though in the end they didn't contribute as much to my application.

Second, it is important to do things you enjoy. I still enjoyed playing the violin and being part of an orchestra, and I really enjoyed my school's academic teams, even though we never went beyond state level. Even if some activities don't contribute as much to your application, it's still fine to spend some time on them—just don't delude yourself into thinking they're stronger than they really are and overspend time on them.

Finally, note that most of my activities were pursued over multiple years. This is a good sign of commitment—rather than hopping from activity year to year, it's better to show sustained commitment, as this is a better signal of genuine passion.

In a future article, I'll break down these activities in more detail. But this guide is already super long, so I want to focus our attention on the main points.

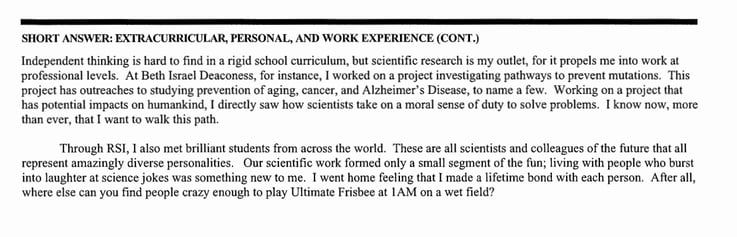

Short Answer: Extracurricular Activities

In today's Common Application, you have 50 characters to describe "Position/Leadership description and organization name" and 150 characters for "Please describe this activity, including what you accomplished and any recognition you received, etc."

Back then, we didn't have as much space per activity, and instead had a short answer question.

The Short Answer prompt:

Please describe which of your activities (extracurricular and personal activities or work experience) has been most meaningful and why.

I chose RSI as my most significant activity for two reasons—one based on the meaning of the work, and another on the social aspect.

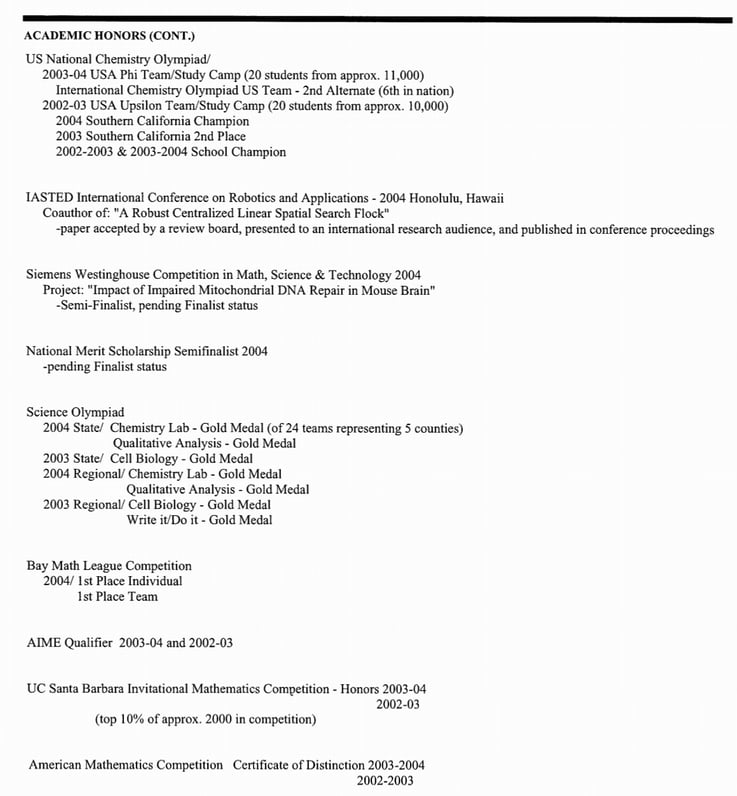

It's obvious that schools like Yale and UChicago want the best students in the world that they can get their hands on. Academic honors and awards are a great, quantifiable way to show that.

Here's the complete list of Academic Honors I submitted. The Common Application now limits you to five honors only (probably because they got tired of lists like these), but chances are you capture the top 98% of your honors with the top five.

Charlie wins a Golden Ticket to Harvard.

I know this is intimidating if you don't already have a prestigious honor. But remember there are thousands of nationally-ranked people in a multitude of honor types, from science competitions to essay contests to athletics to weird talents.

And I strongly believe the #1 differentiator of high school students who achieve things is work ethic, NOT intelligence or talent. Yes, you need a baseline level of competence to get places, but people far undervalue the progress they can make if they work hard and persevere. Far too many people give up too quickly or fatigue without putting in serious effort.

If you're stuck thinking, "well I'm just an average person, and there's no way I'm going to become world-class in anything," then you've already lost before you've begun. The truth is everyone who achieves something of note puts in an incredible amount of hard work. Because this is invisible to you, it looks like talent is what distinguishes the two of you, when really it's much more often diligence.

I talk a lot more about the Growth Mindset in my How To Get a 4.0 GPA guide .

So my Chemistry Olympiad honor formed 90% of the value of this page. Just like extracurriculars, there's a quick dropoff in value of each item after that.

My research work took up the next two honors, one a presentation at an academic conference, and the other (Siemens) a research competition for high school researchers.

The rest of my honors were pretty middling:

- National Merit Scholarship semifinalist pretty much equates to PSAT score, which is far less important than your SAT/ACT score. So I didn't really get any credit for this, and you won't either.

- In Science Olympiad (this is a team-based competition that's not as prestigious as the academic Olympiads I just talked about), I earned a number of 1 st place state and regional medals, but we never made it to nationals.

- I was mediocre at competition math because I didn't train for it, and I won some regional awards but nothing amazing. This is one place I would have spent more time, maybe in the time I'd save by not practicing violin as much. There are great resources for this type of training, like Art of Problem Solving , that I didn't know existed and could've helped me rank much higher.

At the risk of beating a dead horse, think about how many state medalists there are in the country, in the hundreds of competitions that exist . The number of state to national rankers is probably at least 20:1 (less than 50:1 because of variation in state size), so if there are 2,000 nationally ranked students, there are 40,000 state-ranked students in something !

So state honors really don't help you stand out on your Princeton application. There are just too many of them around.

On the other hand, if you can get to be nationally ranked in something, you will have an amazing Spike that distinguishes you.

Now known as: Personal Essay

Now, the dreaded personal statement. Boy, oh boy, did I fuss over this one.

"What is the perfect combination of personal, funny, heartrending, and inspirational?"

I know I was wondering this when I applied.

Having read books like 50 Successful Harvard Application Essays , I was frightened. I didn't grow up as a refugee, wrenched from my war-torn home! I didn't have a sibling with a debilitating illness! How could anything I write compare to these tales of personal strength?

The trite truth is that colleges want to know who you really are . Clearly they don't expect everyone to have had immense personal struggle. But they do want students who are:

- growth-oriented

- introspective

- kind and good-hearted

Whatever those words mean to you in the context of your life is what you should write about.

In retrospect, in the context of MY application, the personal statement really wasn't what got me into Harvard . I do think my Spike was nearly sufficient to get me admitted to every school in the country.

I say "nearly" because, even if you're world-class, schools do want to know you're not a jerk and that you're an interesting person (which is conveyed through your personal essay and letters of recommendation).

Back then, we had a set of different prompts :

What did you think?

I'm still cringing a bit. Parts of this are very smug (see /r/iamverysmart ), and if you want to punch the writer in the face, I don't blame you. I want to as well.

We'll get to areas of improvement later, but first, let's talk about what this personal essay did well.

As I said above, I saw the theme of the snooze button as a VEHICLE to showcase a few qualities I cared about :

1) I fancied myself a Renaissance man (obnoxious, I know) and wanted to become an inventor and creator . I showed this through mentioning different interests (Rubik's cube, chemistry, Nietzsche) and iterating through a few designs for an alarm clock (electric shocks, explosions, Shakespearean sonnet recitation).

2) My personality was whimsical and irreverent. I don't take life too seriously. The theme of the essay—battling an alarm clock—shows this well, in comparison to the gravitas of the typical student essay. I also found individual lines funny, like "All right, so I had violated the divine honor of the family and the tenets of Confucius." At once I acknowledge my Chinese heritage but also make light of the situation.

3) I was open to admitting weaknesses , which I think is refreshing among people taking college applications too seriously and trying too hard to impress. The frank admission of a realistic lazy habit—pushing the Snooze button—served as a nice foil to my academic honors and shows that I can be down-to-earth.

So you see how the snooze button acts as a vehicle to carry these major points and a lot of details, tied together to the same theme .

In the same way, The Walking Dead is NOT a zombie show—the zombie environment is a VEHICLE by which to show human drama and conflict. Packaging my points together under the snooze button theme makes it a lot more interesting than just outright saying "I'm such an interesting guy."

So overall, I believe the essay accomplishes my goals and the main points of what I wanted to convey about myself.

Note that this is just one of many ways to write an essay . It worked for me, but it may be totally inappropriate for you.

Now let's look at this essay's weaknesses.

Looking at it with a more seasoned perspective, some parts of it are WAY too try-hard. I try too hard to show off my breadth of knowledge in a way that seems artificial and embellishing.

The entire introduction with the Rubik's cube seems bolted on, just to describe my long-standing desire to be a Renaissance man. Only three paragraphs down do I get to the Snooze button, and I don't refer again to the introduction until the end. With just 650 words, I could have made the essay more cohesive by keeping the same theme from beginning to end.

Some phrases really make me roll my eyes. "Always hungry for more" and "ever the inventor" sound too forced and embellishing. A key principle of effective writing is to show, not say . You don't say "I'm passionate about X," you describe what extraordinary lengths you took to achieve X.

The mention of Nietzsche is over-the-top. I mean, come on. The reader probably thought, "OK, this kid just read it in English class and now he thinks he's a philosopher." The reader would be right.

The ending: "with the extra nine minutes, maybe I'll teach myself to cook fried rice" is silly. Where in the world did fried rice come from? I meant it as a nod to my Chinese heritage, but it's too sudden to work. I could have deleted the sentence and wrapped up the essay more cleanly.

So I have mixed feelings of my essay. I think it accomplished my major goals and showed the humorous, irreverent side of my personality well. However, it also gave the impression of a kid who thought he knew more than he did, a pseudo-sophisticate bordering on obnoxious. I still think it was a net positive.

At the end of the day, I believe the safest, surefire strategy is to develop a Spike so big that the importance of the Personal Essay pales in comparison to your achievements. You want your Personal Essay to be a supplement to your application, not the only reason you get in.

There are probably some cases where a well-rounded student writes an amazing Personal Essay and gets in through the strength of that. As a Hail Mary if you're a senior and can't improve your application further, this might work. But the results are very variable—some readers may love your essay, others may just think it's OK. Without a strong application to back it up, your mileage may vary.

This is a really fun section. Usually you don't get to read your letter of recommendation because you sign the FERPA waiver. I've also reached out to my letter writers to make sure they're ok with my showing this.

Teacher recommendations are incredibly important to your application. I would say that after your coursework/test scores and activities/honors, they're the 3 rd most important component of your application .

The average teacher sees thousands of students through a career, and so he or she is very well equipped to position you relative to all other students. Furthermore, your teachers are experienced adults—their impressions of you are much more reliable than your impressions of yourself (see my Personal Essay above). They can corroborate your entire Personal Narrative as an outside observer.

The most effective recommendation letters speak both to your academic strengths and to your personality. For the second factor, the teacher needs to have interacted with you meaningfully, ideally both in and out of class. Check out our guide on what makes for effective letters of recommendation .

Starting from sophomore year, I started thinking about whom I connected better with and chose to engage with those teachers more deeply . Because it's standard for colleges to require two teachers in different subjects, I made sure to engage with English and history teachers as well as math and science.

The minimum requirement for a good letter is someone who taught a class in which you did well. I got straight A's in my coursework, so this wasn't an issue.

Beyond this, I had to look for teachers who would be strong advocates for me on both an academic and personal level . These tended to be teachers I vibed more strongly with, and typically these were teachers who demonstrably cared about teaching. This was made clear by their enthusiasm, how they treated students, and how much they went above expectations to help.

I had a lot of teachers who really just phoned it in and treated their job perfunctorily—these people are likely to write pretty blasé letters.

A final note before reading my actual teacher evaluations— you should avoid getting in the mindset where you get to know teachers JUST because you want a good recommendation letter . Your teachers have seen hundreds, if not thousands, of students pass through, and it's much easier to detect insincerity than you think.

If you honestly like learning and are an enthusiastic, responsible, engaging student, a great recommendation letter will follow naturally. The horse should lead the cart.

Read my How to Get a 4.0 GPA for tips on how to interact with teachers in a genuine way that'll make them love you.

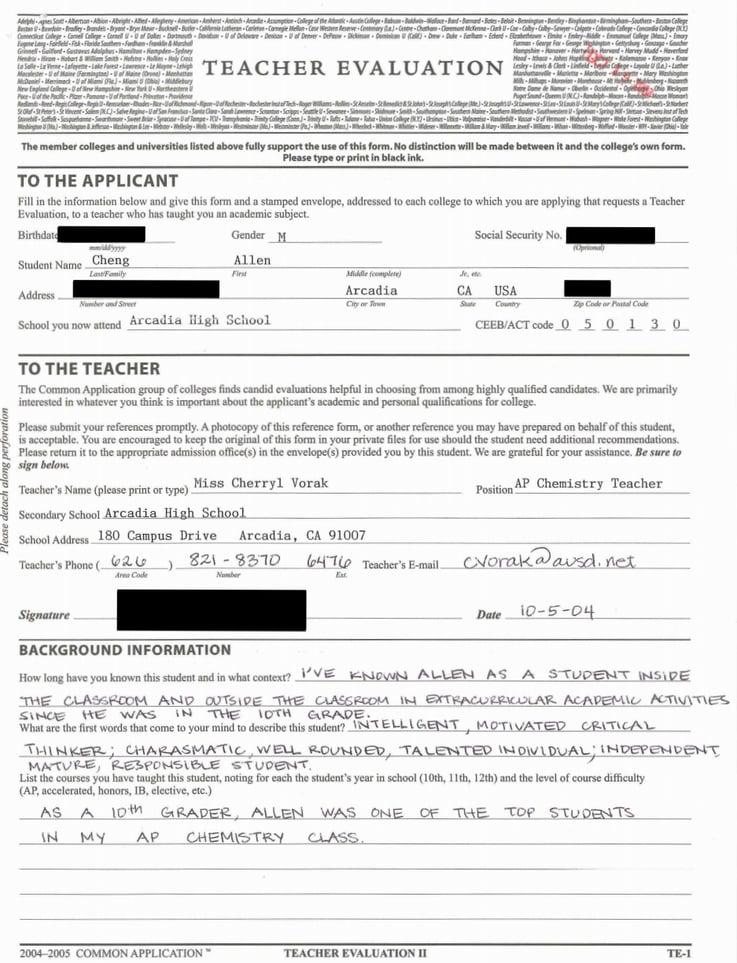

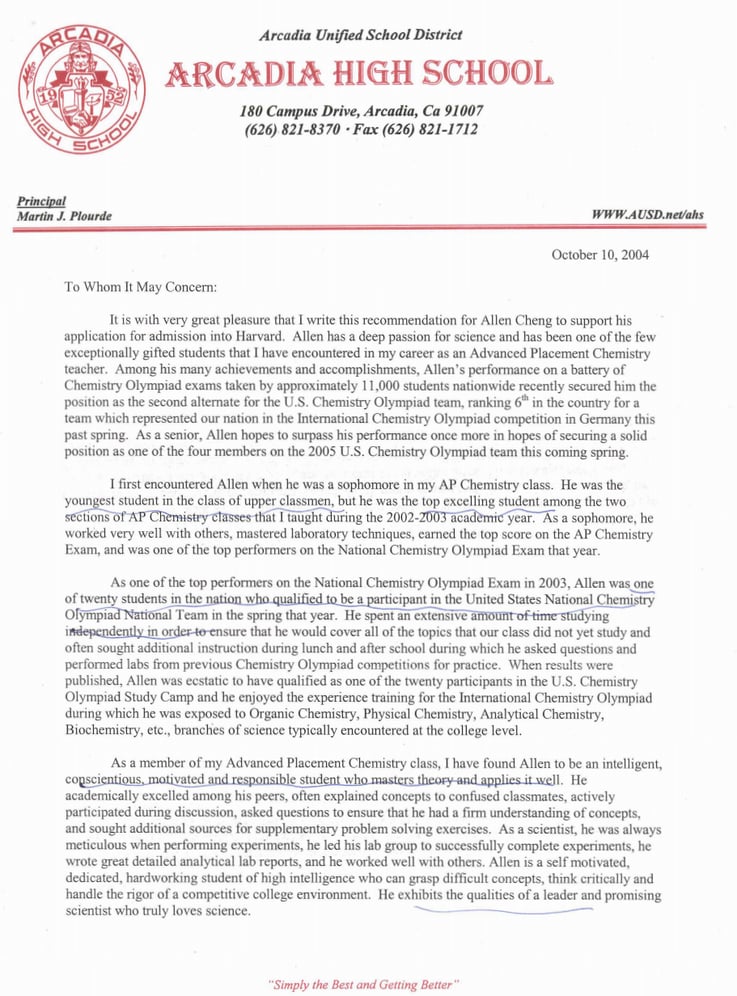

Teacher Letter #1: AP Chemistry Teacher

I took AP Chemistry in 10 th grade and had Miss Cherryl Vorak (now Mynster). She was young, having taught for fewer than 5 years when I had her. She was my favorite teacher throughout high school for these reasons:

- She was enthusiastic, very caring, and spent a lot of time helping struggling students. She exuded pride in her work and seemed to consider teaching her craft.

- She had a kind personality and was universally well liked by her students, even if they weren't doing so well. She was fair in her policies (it probably helped that science is more objective than English). She was also a younger teacher, and this helped her relate to kids more closely.

- She was my advocate for much of the US National Chemistry Olympiad stuff, and in this capacity I got to know her even better outside of class. She provided me a lot of training materials, helped me figure out college chemistry, and directed me to resources to learn more.

By the time of the letter writing, I had known her for two full years and engaged with her continuously, even when I wasn't taking a class with her in junior year. We'd build up a strong relationship over the course of many small interactions.

All of this flowed down to the recommendation you see here. Remember, the horse leads the cart.

First, we'll look at the teacher evaluation page. The Common Application now has 16 qualities to rate, rather than the 10 here. But they're largely the same.

You can see a very strong evaluation here, giving me the highest ratings possible for all qualities.

In today's Common Application, all of these Ratings are retained, aside from "Potential for Growth." Today's Common App also now includes Faculty Respect, Maturity, Leadership, Integrity, Reaction to Setbacks, Concern for Others, and TE Overall. You can tell that the updated Common App places a great emphasis on personality.

The most important point here: it is important to be ranked "One of the top few encountered in my career" for as many ratings as possible . If you're part of a big school, this is CRITICAL to distinguish yourself from other students. The more experienced and trustworthy the teacher, the more meaningful this is.

Again, it's a numbers game. Think about the 20,000+ high schools in the country housing 4 million+ high school students—how many people fit in the top 5% bucket?

Thus, being marked merely as Excellent (top 10%) is actually a negative rating , as far as admissions to top colleges is concerned. If you're in top 10%, and someone else with the SAME teacher recommender is being rated as "One of the top ever," it's really hard for the admissions officer to vouch for you over the other student.

You really want to make sure you're one of the best in your school class, if not one of the best the teacher has ever encountered. You'll see below how you can accomplish this.

Next, let's look at her letter.

As you read this, think— what are the interactions that would prompt the teacher to write a recommendation like this? This was a relationship built up in a period of over 2 years, with every small interaction adding to an overall larger impression.

You can see how seriously they take the letter because of all the underlining . This admissions reader underlined things that weren't even underlined in my application, like my US National Chemistry Olympiad awards. It's one thing for a student to claim things about himself—it's another to have a teacher put her reputation on the line to advocate for her student.

The letter here is very strong for a multitude of reasons. First, the length is notable —most letters are just a page long, but this is nearly two full pages , single spaced. This indicates not just her overall commitment to her students but also of her enthusiastic support for me as an applicant.

The structure is effective: first Miss Vorak talks about my academic accomplishments, then about my personal qualities and interactions, then a summary to the future. This is a perfect blend of what effective letters contain .

On the micro-level, her diction and phrasing are precise and effective . She makes my standing clear with specific statements : "youngest student…top excelling student among the two sections" and "one of twenty students in the nation." She's clear about describing why my achievements are notable and the effort I put in, like studying college-level chemistry and studying independently.

When describing my personality, she's exuberant and fleshes out a range of dimensions: "conscientious, motivated and responsible," "exhibits the qualities of a leader," "actively seeks new experiences," "charismatic," "balanced individual with a warm personality and sense of humor." You can see how she's really checking off all the qualities colleges care about.

Overall, Miss Vorak's letter perfectly supports my Personal Narrative —my love for science, my overall academic performance, and my personality. I'm flattered and grateful to have received this support. This letter was important to complement the overall academic performance and achievements shown on the rest of my application.

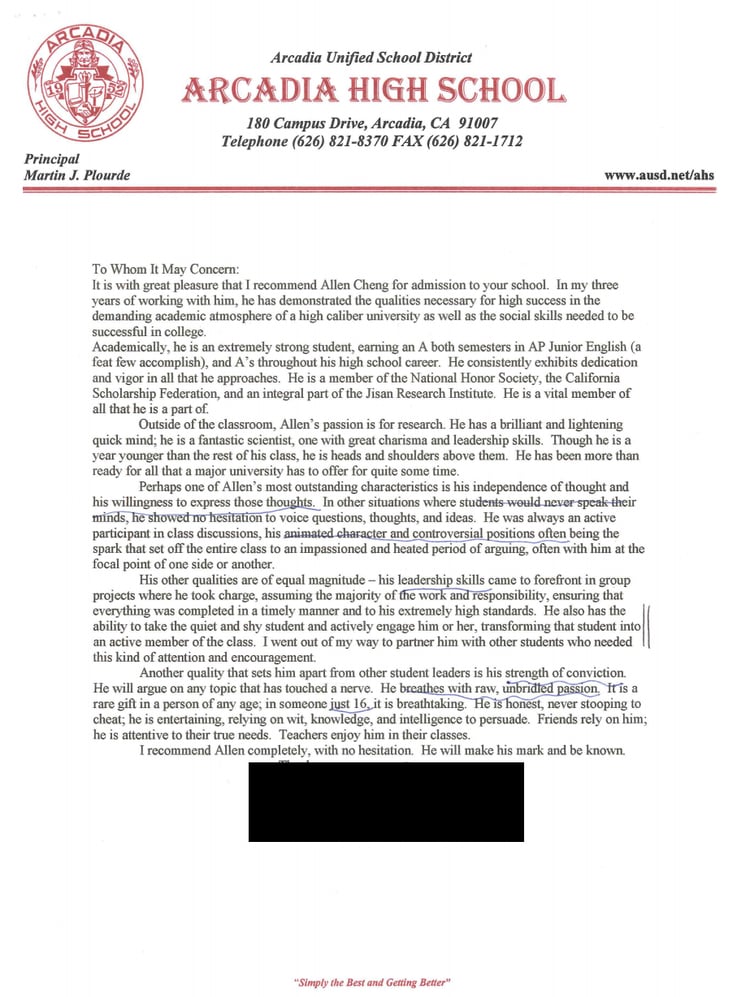

Teacher Letter #2: AP English Language Teacher

My second teacher Mrs. Swift was another favorite. A middle-aged, veteran English teacher, the best way I would describe her is "fiery." She was invigorating and passionate, always trying to get a rise out of students and push their thinking, especially in class discussions. Emotionally she was a reliable source of support for students.

First, the evaluation:

You can see right away that her remarks are terser. She didn't even fill out the section about "first words that come to mind to describe this student."

You might chalk this up to my not being as standout of a student in her mind, or her getting inundated with recommendation letter requests after over a decade of teaching.

In ratings, you can see that I only earned 3 of the "one of the top in my career." There are a few explanations for this. As a teacher's career lengthens, it gets increasingly hard to earn this mark. I probably also didn't stand out as much as I did to my Chemistry teacher—most of my achievement was in science (which she wasn't closely connected to), and I had talented classmates. Regardless, I did appreciate the 3 marks she gave me.

Now, the letter. Once again, as you read this letter, think: what are the hundreds of micro-interactions that would have made a teacher write a letter like this?

Overall, this letter is very strong. It's only one page long, but her points about my personality are the critical piece of this recommendation. She also writes with the flair of an English teacher:

"In other situations where students would never speak their minds, he showed no hesitation to voice questions, thoughts, and ideas."

"controversial positions often being the spark that set off the entire class"

"ability to take the quiet and shy student and actively engage"…"went out of my way to partner him with other students who needed"

"strength of conviction"…"raw, unbridled passion"…"He will argue on any topic that has touched a nerve."

These comments most support the personality aspect of my Personal Narrative—having an irreverent, bold personality and not being afraid of speaking my mind. She stops just short of making me sound obnoxious and argumentative. An experienced teacher vouching for this adds so much more weight than just my writing it about myself.

Teacher recommendations are some of the most important components of your application. Getting very strong letters take a lot of sustained, genuine interaction over time to build mutual trust and respect. If you want detailed advice on how to interact with teachers earnestly, check out my How to Get a 4.0 GPA and Better Grades guide .

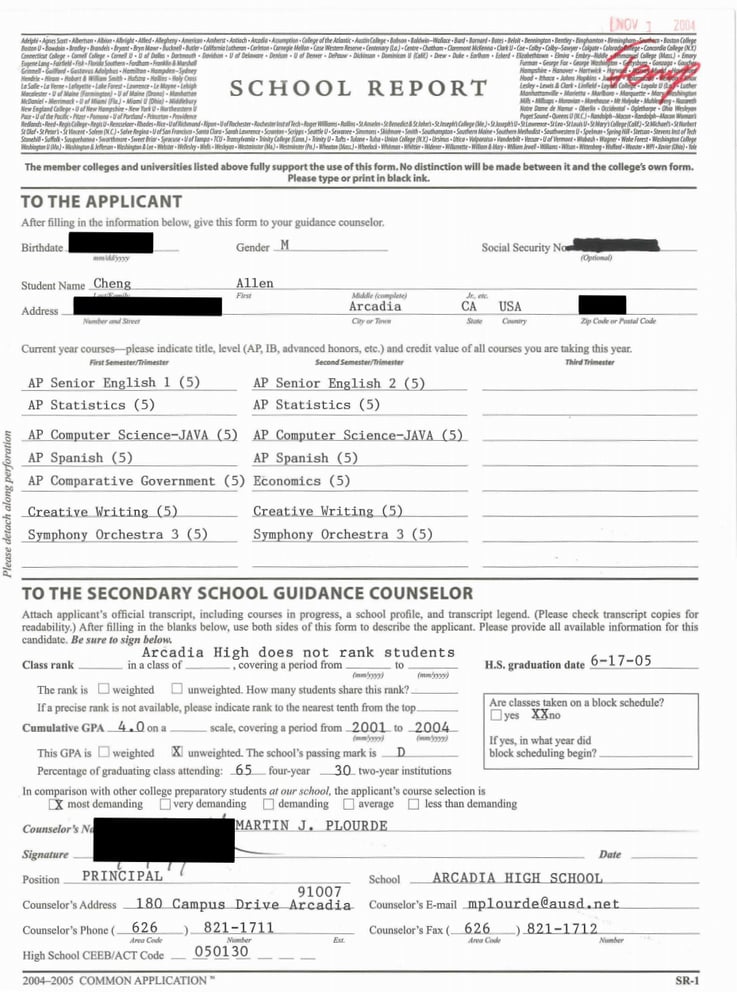

Let's go to the final recommendation, from the school counselor.

Now known as: School Report

The first piece of this is reporting your academic status and how the school works overall. There's not much to say here, other than the fact that my Principal wrote my recommendation for me, which we'll get into next.

Counselor Recommendation

Now known as: Counselor Recommendation

Let's talk about my school principal writing my recommendation, rather than a school counselor.

This was definitely advantageous—remember how, way up top in Educational Data, the reader circled the "Principal." Our Principal only wrote a handful of these recommendations each year , often for people who worked closely with him, like student body presidents. So it was pretty distinctive that I got a letter from our Principal, compared to other leading applicants from my school.

This was also a blessing because our counseling department was terrible . Our school had nearly 1,000 students per grade, and only 1 counselor per grade. They were overworked and ornery, and because they were the gatekeepers of academic enrollment (like class selection and prerequisites), this led to constant frictions in getting the classes you wanted.

I can empathize with them, because having 500+ neurotic parents pushing for advantages for their own kids can get REALLY annoying really fast. But the counseling department was still the worst part of our high school administration, and I could have guessed that the letters they wrote were mediocre because they just had too many students.

So how did my Principal come to write my recommendation and not those for hundreds of other students?

I don't remember exactly how this came to be, to be honest. I didn't strategize to have him write a letter for me years in advance. I didn't even interact with him much at all until junior year, when I got on his radar because of my national rankings. Come senior year I might have talked to him about my difficulty in reaching counselors and asked that he write my recommendation. Since I was a top student he was probably happy to do this.

He was very supportive, but as you can tell from the letter to come, it was clear he didn't know me that well.

Interestingly, the prompt for the recommendation has changed. It used to start with: "Please write whatever you think is important about this student."

Now, it starts with: " Please provide comments that will help us differentiate this student from others ."

The purpose of the recommendation has shifted to the specific: colleges probably found that one counselor was serving hundreds of students, so the letters started getting mushy and indistinguishable from each other.

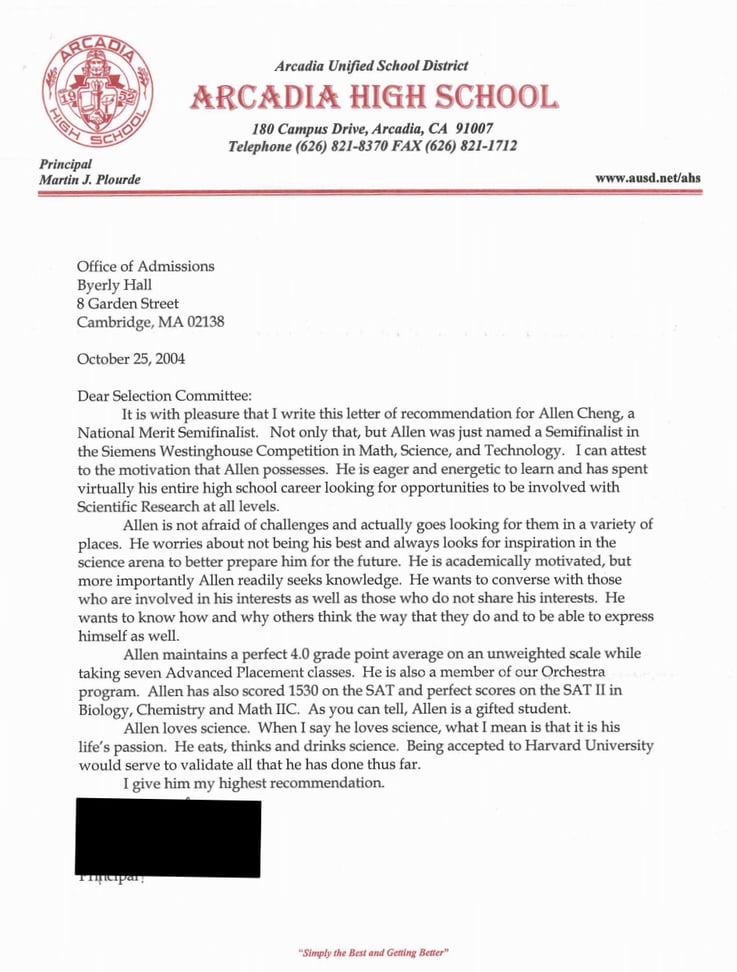

Here's the letter:

This letter is probably the weakest overall of all my letters. It reads more like a verbal resume than a personal account of how he understands me.

Unlike my two teacher recommendations, he doesn't comment on the nature of our interactions or about my personality (because he truly didn't understand them well). He also misreported by SAT score as 1530 instead of 1600 (I did score a 1530 in an early test, but my 1600 was ready by January 2004, so I don't know what source he was using).

Notably, the letter writer didn't underline anything.

I still appreciate that he wrote my letter, and it was probably more effective than a generic counselor letter. But this didn't add much to my application.

At this point, we've covered my entire Common Application. This is the same application I sent to every school I applied to, including Harvard, Princeton, and Stanford. Thanks for reading this far—I hope you've gotten a lot out of this already.

If you keep reading to the end, I'll have advice for both younger students and current applicants to build the strongest application possible.

Next, we'll go over the Harvard Supplemental Application, which of course is unique to Harvard.

For most top colleges like Princeton, Yale, Stanford, Columbia, and so on, you will need to complete a supplemental application to provide more info than what's listed on the Common Application.

Harvard was and is the same. The good news is that it's an extra chance for you to share more about yourself and keep pushing your Personal Narrative.

There are four major components here:

- The application form

- Writing supplement essay

- Supplementary recommendations

- Supplemental application materials

I'll take you through the application section by section.

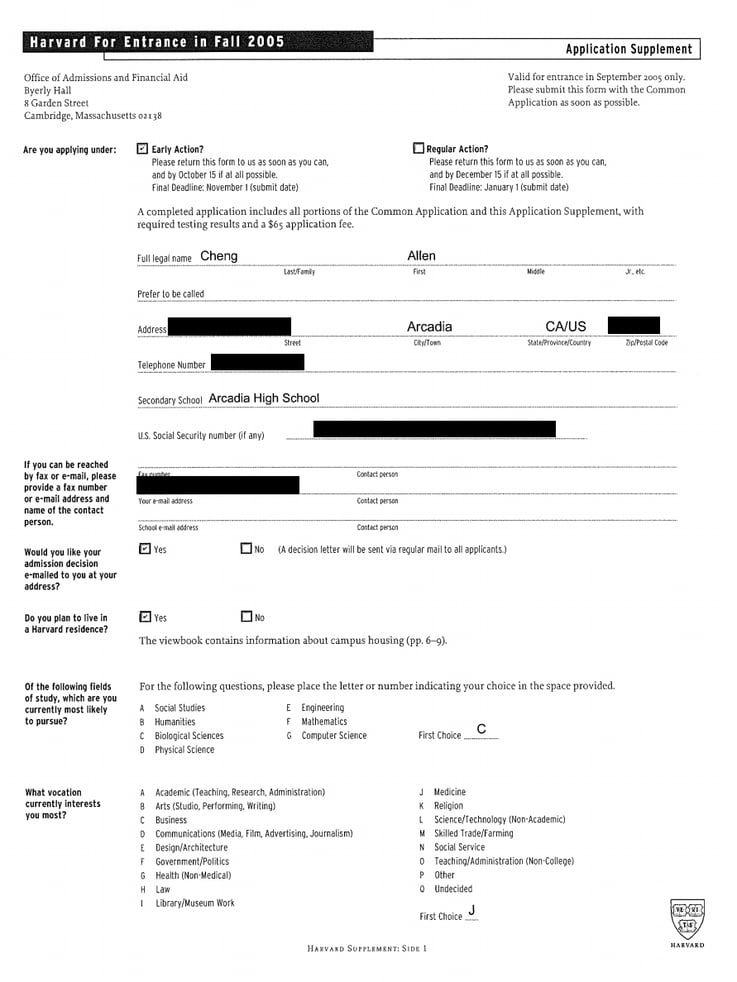

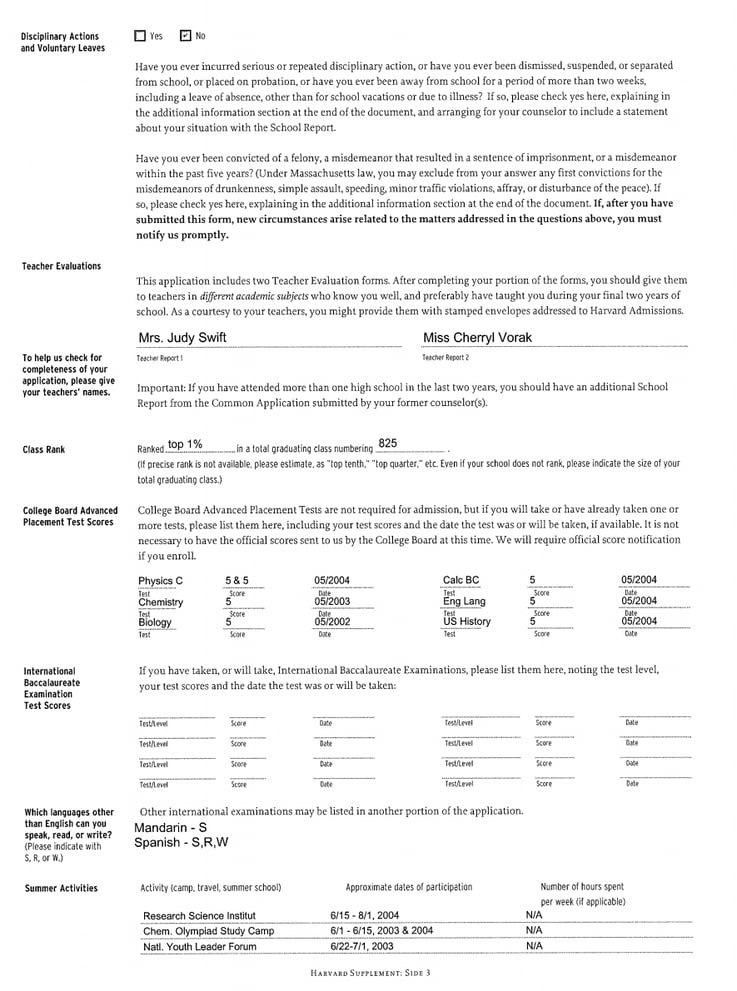

Harvard Supplement Form

First, the straightforward info and questions.

This section is pretty straightforward and is similar to what you'd see on a Columbia application.

I planned to live in a Harvard residence, as most students do.

Just as in my Common App, I noted that I was most likely to study biological sciences, choose Medicine as my vocation, and participate in orchestra, writing, and research as my extracurriculars. Nothing surprising here—it's all part of my Personal Narrative.

Interestingly, at the time I was "absolutely certain" about my vocational goals, which clearly took a detour once I left medical school to pursue entrepreneurship to create PrepScholar...

I had the space to list some additional honors, where I listed some musical honors that didn't make the cut in my Common App.

Here are the next two pages of the Harvard supplemental form.

The most interesting note here is that the admissions officer wrote a question mark above "Music tape or CD." Clearly this was inconsistent with my Personal Narrative —if violin was such an important part of my story, why didn't I want to include it?

The reason was that I was actually pretty mediocre at violin and was nowhere near national-ranked. Again, remember how many concertmasters in the thousands of orchestras there are in the world—I wasn't good enough to even be in the top 3 chairs in my school orchestra (violin was very competitive).

I wanted to focus attention on my most important materials, which for my Personal Narrative meant my research work. You'll see these supplementary materials later.

Additional Essays

Now known as: Writing Supplement

For the most part, the Harvard supplemental essay prompt has stayed the same. You can write about a topic of your choice or about any of the suggestions. There are now two more prompts that weren't previously there: "What you would want your future college roommate to know about you" and "How you hope to use your college education."

Even though this is optional, I highly recommend you write something here. Again, you have so few chances in the overall application to convey your personal voice—an extra 500 words gives you a huge opportunity. I would guess that the majority of admitted Harvard students submit a Writing Supplement.

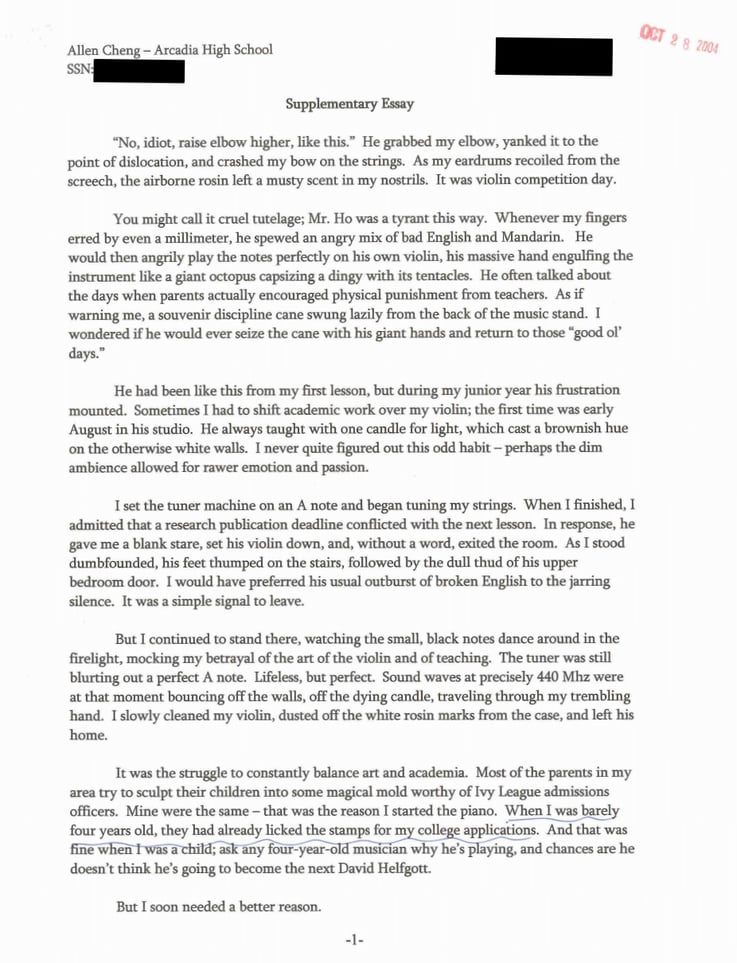

After a lot of brainstorming, I settled on the idea that I wanted to balance my application by writing about the major non-academic piece of my Personal Narrative—my music training . Also, I don't think I explicitly recognized this at the time, but I wanted to distance myself from the Asian-American stereotype—driven entirely by parent pressure, doing most things perfunctorily and without interest. I wanted to show I'd broken out of that mold.

Here's my essay:

Reading it now, I actually think this was a pretty bad essay, and I cringe to high heaven. But once again, let's focus on the positive first.

I used my violin teacher as a vehicle for talking about what the violin meant to me. (You can tell I love the concept of the vehicle in essays.) He represented passion for the violin—I represented my academic priorities. Our personal conflict was really the conflict between what we represented.

By the end of the essay, I'd articulated the value of musical training to me—it was cathartic and a way to balance my hard academic pursuits.

Halfway in the essay, I also explicitly acknowledged the Asian stereotype of parents who drove their kids, and said my parents were no different. The reader underlined this sentence. By pointing this out and showing how my interest took on a life of its own, I wanted to distance myself from that stereotype.

So overall I think my aims were accomplished.

Despite all that, this essay was WAY overdramatic and overwrought . Some especially terrible lines:

"I was playing for that cathartic moment when I could feel Tchaikovsky himself looking over my shoulder."

"I was wandering through the fog in search of a lighthouse, finally setting foot on a dock pervaded by white light."

OK, please. Who really honestly feels this way? This is clumsy, contrived writing. It signals insincerity, actually, which is bad.

To be fair, all of this is grounded in truth. I did have a strict violin teacher who did get pretty upset when I showed lack of improvement. I did appreciate music as a diversion to round out my academic focus. I did practice hard each day, and I did have a pretty gross callus on my pinky.

But I would have done far better by making it more sincere and less overworked.

As an applicant, you're tempted to try so hard to impress your reader. You want to show that you're Worthy of Consideration. But really the best approach is to be honest.

I think this essay was probably neutral to my application, not a strong net positive or net negative.

Supplementary Recommendations

Harvard lets you submit letters from up to two Other Recommenders. The Princeton application, Penn application, and others are usually the same.

Unlike the other optional components (the Additional Information in the Common App, and the Supplementary Essay), I would actually consider these letters optional. The reader gets most of the recommendation value from your teacher recommendations—these are really supplementary.

A worthwhile Other Recommender:

- has supervised an activity or honor that is noteworthy

- has interacted with you extensively and can speak to your personality

- is likely to support you as one of the best students they've interacted with

If your Other Recommenders don't fulfill one or more of these categories, do NOT ask for supplementary letters. They'll dilute your application without adding substantively to it.

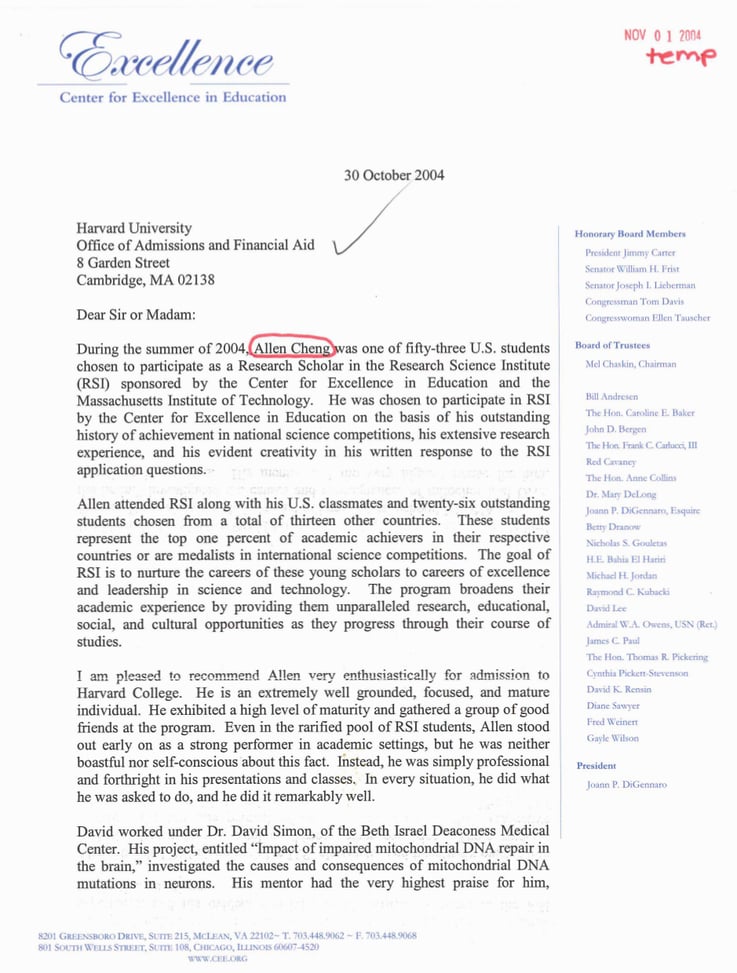

To beat a dead horse, the primary component of my Personal Narrative was my science and research work. So naturally I chose supervisors for my two major research experiences to write supplemental letters.

First was the Director of Research Science Institute (the selective summer research program at MIT). The second was from the head of Jisan Research Institute, where I did Computer Science research.

This letter validates my participation in RSI and incorporates the feedback from my research mentor, David Simon. At the time, the RSI students were the most talented students I had met, so I'm also flattered by some of the things the letter writer said, like "Allen stood out early on as a strong performer in academic settings."

I didn't get to know the letter writer super well, so he commented mainly on my academic qualifications and comments from my mentor.

My mentor, who was at one of the major Harvard-affiliated hospitals, said some very nice things about my research ability, like:

"is performing in many ways at the level of a graduate student"

"impressed with Allen's ability to read even advanced scientific publications and synthesize his understanding"

Once again, it's much more convincing for a seasoned expert to vouch for your abilities than for you to claim your own abilities.

My first research experience was done at Jisan Research Institute, a small private computer science lab run by a Caltech PhD. The research staff were mainly high school students like me and a few grad students/postdocs.

My research supervisor, Sanza Kazadi, wrote the letter. He's requested that I not publish the letter, so I'll only speak about his main points.

In the letter, he focused on the quality of my work and leadership. He said that I had a strong focus in my work, and my research moved along more reliably than that of other students. I was independent in my work in swarm engineering, he says, putting together a simulation of the swarm and publishing a paper in conference proceedings. He talked about my work in leading a research group and placing a high degree of trust in me.

Overall, a strong recommendation, and you get the gist of his letter without reading it.

One notable point—both supplemental letters had no marks on them. I really think this means they place less emphasis on the supplementary recommendations, compared to the teacher recommendations.

Finally, finally, we get to the very last piece of my application.

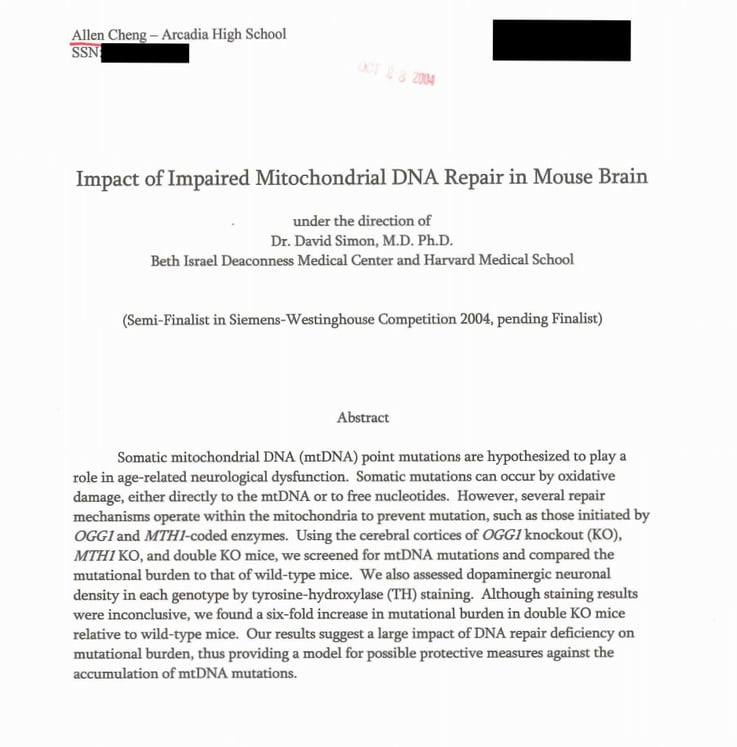

Let me beat the dead horse even deader. Because research was such a core part of my Personal Narrative, I decided to include abstracts of both of my papers. The main point was to summarize the body of work I'd done and communicate the major results.

As Harvard says, "These materials are entirely optional; please only submit them if you have unusual talents."

This is why I chose not to submit a tape of my music: I don't think my musical skill was unusually good.

And frankly, I don't think my research work was that spectacular. Unlike some of my very accomplished classmates, I hadn't ranked nationally in prestigious competitions like ISEF and Siemens. I hadn't published my work in prominent journals.

Regardless, I thought these additions would be net positive, if only marginally so.

I made sure to note where the papers had been published or were entering competitions, just to ground the work in some achievement.

Keep Reading

At PrepScholar, we've published the best guides available anywhere to help you succeed in high school and college admissions.

Here's a sampling of our most popular articles:

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score / Perfect ACT Score —Learn the strategies I used to get a perfect 1600 on the SAT, and a perfect 36 on the ACT.

SAT 800 Series: Reading | Math | Writing —Learn important strategies to excel in each section of the SAT.

ACT 36 Series: English | Math | Reading | Science —Learn how to get a perfect 36 on each section of the ACT.

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League —The foundational guide where I discuss the philosophy behind what colleges are looking for, how to develop a Spike, and why being well-rounded is the path to rejection.

How to Get a 4.0 GPA and Better Grades —Are you struggling with getting strong grades in challenging coursework? I step you through all the major concepts you need to excel in school, from high-level mindset to individual class strategies.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

As co-founder and head of product design at PrepScholar, Allen has guided thousands of students to success in SAT/ACT prep and college admissions. He's committed to providing the highest quality resources to help you succeed. Allen graduated from Harvard University summa cum laude and earned two perfect scores on the SAT (1600 in 2004, and 2400 in 2014) and a perfect score on the ACT. You can also find Allen on his personal website, Shortform , or the Shortform blog .

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

- College , Uncat

How to Write the Harvard Supplemental Essays 2020-2021

- July 20, 2020

Harvard University is without a doubt one of the most well-known schools anywhere in the world. To nobody’s surprise, it’s also one of the most selective. With an acceptance rate of less than 5%, the competition to receive an acceptance letter from this college is naturally very high. So if you’ve got your heart set on strolling through Harvard Yard in a crimson sweatshirt, use the Harvard supplemental essays 2020-2021 to show admissions officers that you’re not just in it for the bragging rights .

Choose supplemental essay topics that allow you to discuss your interests and goals by showing admissions officers how you think and act. To guide you through the prompts for this year, I’ve outlined each question, elaborated on the approaches you should take, and added more tips to help you make the most out of your Harvard supplemental essays 2020-2021 .

Prompts for the Harvard Supplemental Essays 2020-2021

Required questions.

Your intellectual life may extend beyond the academic requirements of your particular school. Please use the space below to list additional intellectual activities that you have not mentioned or detailed elsewhere in your application. These could include, but are not limited to, supervised or self-directed projects not done as school work, training experiences, online courses not run by your school, or summer academic or research programs not described elsewhere. (150 words)

Hidden in the Academics section under Harvard’s Common Application tab, this prompt asks you to share your intellectual curiosity. Since the school can already see your courses and grades, it wants to know whether you’ve expanded beyond just your regular required schoolwork. Harvard appreciates students who have taken the initiative to strive for academic growth, so don’t miss out on the chance to talk about your intellectual pursuits.

Even though the prompt says to “list,” if you have space, mention one or two facts about the courses or projects, such as your motivations behind pursuing them, whether they have impacted your goals, and your biggest takeaways from the experiences. Since admissions officers want to see whether you’re an individual who isn’t shy about pursuing new opportunities, take advantage of this prompt to provide new information about yourself that they might not have guessed from the rest of your application.

Please briefly elaborate on one of your extracurricular activities or work experiences. (150 words)

When admissions officers read your answers to the Harvard supplemental essays 2020-2021 , they want to know whether you’ve fully taken advantage of your extracurricular opportunities. They’ll also use this mini essay – tucked in under the Activities section – to gauge how you might contribute to the Harvard community, so it would also be wise to choose an activity that you’re genuinely passionate about and can see yourself continuing after high school.

In order to make the most out of this essay, write about an activity that you haven’t described in your personal statement, preferably one where you’ve demonstrated leadership and can highlight tangible achievements. Talk about why the activity appeals to you, what it has taught you or if it has inspired growth in some way. Since you don’t have a lot of space, make sure to use your words carefully and elaborate on your commitment as much as you possibly can.

Related Posts

InGenius Prep’s 2025 Early Admissions Results

The Secret to Stellar Letters of Recommendation

Mastering The Additional Information Section & SRAR

View all posts, webinars you might like, high school trends for middle schoolers.

- The evolving academic landscape: What subjects and skills are in high demand?

- Social dynamics and expectations: How to navigate friendships, peer pressure, and more.

- The extracurricular scene: What clubs, sports, and activities will help you shine?

- Essential tips for a smooth transition: How to set yourself up for success from day one.

Step-By-Step Guide For Graduate School

- Admissions Edge: Gain valuable tips on how to differentiate yourself from other applicants and make a lasting impression on admissions committees.

- Program Selection: Discover how to choose the right graduate program aligned with your academic interests and career goals.

- Application Mastery: Learn the ins and outs of crafting a standout application, including personal statements, letters of recommendation, and transcripts.

Pursue Your Reach Schools with InGenius Prep and Increase Your Admissions Chances

- Editor's Pick

- Career Guide

HMS Is Facing a Deficit. Under Trump, Some Fear It May Get Worse.

Cambridge Police Respond to Three Armed Robberies Over Holiday Weekend

What’s Next for Harvard’s Legacy of Slavery Initiative?

MassDOT Adds Unpopular Train Layover to Allston I-90 Project in Sudden Reversal

Denied Winter Campus Housing, International Students Scramble to Find Alternative Options

10 Successful Harvard Application Essays | 2020

Our new 2022 version is up now!

Our 2022 edition is sponsored by HS2 Academy—a premier college counseling company that has helped thousands of students gain admission into Ivy League-level universities across the world. Learn more at www.hs2academy.com . Also made possible by The Art of Applying, College Confidential, Crimson Education, Dan Lichterman, Key Education, MR. MBA®, Potomac Admissions, Prep Expert, and Prepory.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Harvard Essay 2024-2025

Harvard essay: quick facts.

- Harvard acceptance rate: 3% — U.S. News ranks Harvard as #3 on its National Universities list. Harvard is one of the most competitive schools in the world, which makes writing your Harvard essay one of the most important tasks in your college application process.

- 5 short answer (~150 word) essays

- Harvard application note: Harvard University accepts both the Common Application and the Coalition Application by Scoir. When applying , students will complete the personal statement as well as the five Harvard supplemental essays.

- #1 Harvard essay tip: Harvard is a competitive, elite Ivy League university. Therefore, you’ll want to make sure you give yourself plenty of time to complete the application, including the essays, to the best of your ability.

Where is Harvard?

Harvard University is one of the eight Ivy League universities in the United States. It is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Founded in 1636, Harvard has been a leader among higher education institutions for centuries. It is a medium-sized university with over 7,000 undergraduate students. Its campus is idyllic for those looking to study in New England. Just over 5,600 acres, the campus is filled with historic buildings in which students receive one of the most renowned educations in the world.

Applying to Harvard University

With an acceptance rate of just 3%, Harvard admissions receives — and rejects — many qualified candidates each admissions cycle. For that reason, your Harvard application needs to stand out from the crowd. All applicants will have high grades and impressive extracurricular activities. As such, each Harvard application essay is a new opportunity to impress admissions .

The Harvard supplemental essays make up a significant part of the application. Every Harvard essay is an opportunity to show a new part of yourself that hasn’t been seen elsewhere in your application. When applying to Harvard, you need to tell a compelling story. The five Harvard supplemental essays and the Harvard personal statement will help you do so.

In addition to the Harvard application essays, students will also complete the Harvard personal statement. This is also known as the Common App or Coalition App personal statement.

Harvard Personal Statement

As a part of the Harvard application essay requirements, students must complete the Harvard personal statement. Depending on which application platform you decide to use, the Harvard personal statement prompts will vary. That is to say, the Common Application has different prompts from the Coalition Application. However, the five Harvard essay prompts for the supplemental essays are the same, no matter the application platform.

The Harvard personal statement is an important part of your overall application. Keep in mind that you will likely send your personal statement to various schools. Since your Harvard personal statement should ideally add new and valuable information to your candidate profile, think about your supplemental essays in relation to the personal statement. You don’t want your Harvard personal statement to repeat information from a different Harvard application essay.

What are the Harvard supplemental essays?

The Harvard essay requirements for the 2024–2025 admissions cycle are straightforward. Students must submit five short answer supplemental essays in addition to the Harvard personal statement. Essay requirements can change yearly, so it’s important to stay on top of your schools’ requirements.

Harvard admissions wants to learn more about applicants through every Harvard essay. No one Harvard application essay is more important than another. Therefore, you should give each Harvard essay the attention it deserves to craft an outstanding overall application.

Wondering what this year’s Harvard essay prompts are? Here are the current five short answer Harvard application essay prompts:

Harvard has long recognized the importance of enrolling a diverse student body. How will the life experiences that shape who you are today enable you to contribute to Harvard?

Top 3 things your roommates might like to know about you., how do you hope to use your harvard education in the future, briefly describe any of your extracurricular activities, employment experience, travel, or family responsibilities that have shaped who you are., describe a time when you strongly disagreed with someone about an idea or issue. how did you communicate or engage with this person what did you learn from this experience.

The Harvard essay prompts have a word limit of 150 words. These are indeed short answer essays, so you’ll need to choose your words carefully when responding to the Harvard essay prompts.

What should I write my Harvard essay about?

Choosing the topic to respond to these Harvard essay prompts can feel overwhelming. You may have many possible topics you’d like to write on, or maybe you have absolutely no idea what to say. Don’t worry! There are plenty of ways to get ideas for your Harvard supplemental essays.

Consider reading Harvard essay examples or Ivy League essay examples . Although the Harvard essay prompts may change yearly, reading Harvard essay examples can help get you started on your unique story. You’ll be able to see what makes a successful Harvard essay. However, when reading Harvard essay examples, don’t simply reuse a topic in your own essay. Your topic should be unique, personal, and meaningful to you. Essay examples should just be used to get you started when brainstorming potential topics.

Keep in mind that each Harvard essay should share something new with admissions. That’s why it’s important to choose topics that don’t simply reiterate other parts of your application . Harvard is a competitive school, and every candidate is well qualified. Writing an impressive Harvard essay is an opportunity to stand out and impress. So choose your topics carefully!

Harvard Short Answer Questions

Each Harvard essay is an important part of the application. That can be stressful to think about, since essay writing can be time consuming even when you have a great idea. Of course, it’s even more stressful if you don’t plan ahead or aren’t comfortable with writing in this format. Luckily, Harvard offers some tips on filling out their application. Additionally, doing your research on Harvard will help when writing the Harvard supplemental essays. Learn the ins and outs of Harvard’s admissions process , as well as different opportunities only available at Harvard.

Now, let’s dive into how to approach the Harvard essay prompts.

Harvard Essay #1- Contributing to Harvard

The first of the Harvard essay prompts asks applicants to consider what they will bring to Harvard’s campus. Here’s the first Harvard essay prompt:

This essay is a take on the classic diversity essay . As such, you’ll want to consider important aspects of your background, identity, culture, personality, or upbringing that have made you who you are. What lived experiences have defined your values, goals, or perspectives? How will where you came from impact what you bring to Harvard’s campus?

“Life experiences” is a broad term. This means that you have plenty of room for interpretation in this Harvard essay. Really, the most important part of this Harvard essay is choosing a meaningful topic that shows what sets you apart from the crowd. It could be something as simple as a unique hobby. For example, you might write about how instead of keeping a journal, you write short stories loosely based on your life.

The second part of this Harvard essay asks you to show how this part of your identity will inform your time at Harvard. Harvard needs to know that you will make a positive impact on their campus community by bringing a unique perspective. Going back to our previous example, maybe by romanticizing your daily life with short stories, you’ve found an appreciation for the little things. This gratitude makes you more prepared to take on any obstacles in life.

Harvard Essay #2- Harvard Roommate Essay

While the first Harvard essay prompt was a college essay classic, the second is a bit more quirky.