Academic Reading Strategies

Completing reading assignments is one of the biggest challenges in academia. However, are you managing your reading efficiently? Consider this cooking analogy, noting the differences in process:

Taylor’s process was more efficient because his purpose was clear. Establishing why you are reading something will help you decide how to read it, which saves time and improves comprehension. This guide lists some purposes for reading as well as different strategies to try at different stages of the reading process.

Purposes for reading

People read different kinds of text (e.g., scholarly articles, textbooks, reviews) for different reasons. Some purposes for reading might be

- to scan for specific information

- to skim to get an overview of the text

- to relate new content to existing knowledge

- to write something (often depends on a prompt)

- to critique an argument

- to learn something

- for general comprehension

Strategies differ from reader to reader. The same reader may use different strategies for different contexts because their purpose for reading changes. Ask yourself “why am I reading?” and “what am I reading?” when deciding which strategies to try.

Before reading

- Establish your purpose for reading

- Speculate about the author’s purpose for writing

- Review what you already know and want to learn about the topic (see the guides below)

- Preview the text to get an overview of its structure, looking at headings, figures, tables, glossary, etc.

- Predict the contents of the text and pose questions about it. If the authors have provided discussion questions, read them and write them on a note-taking sheet.

- Note any discussion questions that have been provided (sometimes at the end of the text)

- Sample pre-reading guides – K-W-L guide

- Critical reading questionnaire

During reading

- Annotate and mark (sparingly) sections of the text to easily recall important or interesting ideas

- Check your predictions and find answers to posed questions

- Use headings and transition words to identify relationships in the text

- Create a vocabulary list of other unfamiliar words to define later

- Try to infer unfamiliar words’ meanings by identifying their relationship to the main idea

- Connect the text to what you already know about the topic

- Take breaks (split the text into segments if necessary)

- Sample annotated texts – Journal article · Book chapter excerpt

After reading

- Summarize the text in your own words (note what you learned, impressions, and reactions) in an outline, concept map, or matrix (for several texts)

- Talk to someone about the author’s ideas to check your comprehension

- Identify and reread difficult parts of the text

- Define words on your vocabulary list (try a learner’s dictionary ) and practice using them

- Sample graphic organizers – Concept map · Literature review matrix

Works consulted

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2002). Teaching and researching reading. Harlow: Longman.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout (just click print) and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

- Subject Guides

Being critical: a practical guide

- Reading academic articles

- Being critical

- Critical thinking

- Evaluating information

- Critical reading

- Critical writing

"Academic texts are not meant to be read through from beginning to end."

Academic literature is pitched at an ‘academic audience’ who will already have an understanding of the topic. Academic texts can be complicated and difficult to read, but you don't necessarily have to read every word of a piece of academic writing to get what you need from it. On this page we'll take a look at strategies for reading the most common form of academic literature: the academic journal article . But these strategies may also be applied to other forms of academic writing (and in some cases even to non-academic sources of information). We'll ask ourselves why we're doing the reading in the first place, before examining the typical structure(s) of an article , from abstract to conclusion , and considering the best route through . We'll also take a look at the best strategies for reading .

Journal articles

One of the most common academic sources is the journal article . Researchers publish their research in academic journals which usually cover a specific discipline. Journals used to be printed magazines but now they're mostly published online. Some journals have stronger reputations and more rigorous editorial controls than others.

Types of article

There are all sorts of different types of journal article. The article's title might make it clear what type it is, but other aspects of the article will also give you a clue.

Research / Empirical

Results of studies or experiments, written by those who conducted them. They're built around observation or experiment, and generally start with (or at least have a prominent) methodology.

Descriptions of an individual situation in detail, identify characteristics, findings, or issues, and analyse the case using relevant methodologies or theoretical frameworks.

Summaries of other studies, identifying trends to draw broader conclusions. We look at these in more detail in our section on review articles .

Theoretical

Scholarly articles regarding abstract principles in a specific field of knowledge, not tied to empirical research or data. They may be predictive, and based upon an understanding of the field. They generally start with a background section or a literature review.

Real world techniques, workflows etc. This type of article is generally found in trade / professional journals which are aimed at a professional or practicing audience rather than an academic one.

Peer review

Most good quality journals (and even some bad ones) employ a process called peer-review whereby submitted articles are vetted by a panel of fellow experts in the field. The peer-review panel may demand extensive re-writes of an article to bring it to an acceptable standard for publication. Flaws in the methodology may be highlighted and the author will then have to address these in the text. The result should be that the published work is reliable and of a high standard, and this is usually the case (though not always, as this blog post on the problems with Peer Review explains). Many databases will let you filter to exclude work that hasn't been peer-reviewed.

Finding articles

You could read every journal that's published on your subject, but that's probably a lot of journals. Fortunately, there are databases which catalogue the contents of a selection of journals. You can search these databases to find the articles that will be of use to you.

What are we reading it for anyway?

Maybe we're reading an academic article or similar text for fun, or for our own personal enlightenment, in which case we'll probably want to savour every word of it. But more often than not there are other interests at play:

- To update your knowledge on progress in a particular area or field of study

- To find a solution to a specific problem

- To understand the causes of a particular issue, problem, or situation

- To understand certain fundamental aspects, concepts, or theories

- To inform your own research and help you select an appropriate methodology

- To find support for your own views and arguments

- To impress others

- Because the article has been assigned to you by your tutor and so you've got to read it!

Why we're reading the article will inform how we go about it. If we're after a specific piece of information we just need to find that information; there's no point reading every single word.

Ask yourself:

- Why am I reading this?

- What do I want to get out of it?

- What do I already know?

- How will I know when I have read enough?

The structure of an academic article

Broadly speaking there are two main categories of academic article: empirical and theoretical . The former tends to be associated with the sciences (including social sciences), and the latter with the arts and humanities, though there may be cases where a science or social science paper is theoretical and an arts or humanities paper is empirical.

The typical sections of an article

These are the typical sections you'll find in an academic article (obviously, these are only a guide, and headings and structures may vary in practice):

Empirical paper

Abstract — a summary of the content.

Introduction — identifies the gaps in the existing knowledge, and outlines the aims of the paper.

Methodology — explains the design of the study, and what took place.

Results — explains what the outcome of the study was.

Discussion & Conclusion — interprets the results and makes recommendations based on that interpretation.

Theoretical paper

Body — considers the background of the topic and any competing analyses.

Summary — considers how the various arguments relate.

Discussion & Conclusion — interprets the analysis and makes recommendations accordingly.

What to get from each section

Each of the sections can tell you some useful information. You don't need to read every section to get what you need.

Abstract — a good starting point for understanding the scope and outcome.

Introduction — you can generally skip an introduction, though it may help give you some context.

Methodology — pay attention to the validity of the study design – is it appropriate?

Results — have any results been ignored?

Discussion & Conclusion — is the analysis valid?

Body — has anything been missed?

Summary — are the arguments well founded?

The route through

You don't need to read every word of an article to get what you need from it. Academic articles are pretty-much always split up into sections, and these sections tend to follow a fairly consistent pattern. Skipping around these sections (rather than reading them in order) allows you to appraise the article more quickly, helping you decide whether or not you need to read any more of it.

Title & abstract

"Let's start at the very beginning / a very good place to start"

– Maria Rainer

If by 'the very beginning' Maria meant 'the title ', then yes, it is a pretty decent starting point. It will give us a clue as to the type of article we're looking at, which will help determine our next steps.

The abstract is another obvious place to begin the journey. The abstract provides a summary of the article, including the key findings, so reading an abstract is a lot quicker than reading a whole article.

But be aware that the abstract will have been written by the authors of the article, and so won’t be a neutral account of the research finding. Don’t be too accepting of what is presented: make sure you think critically about what's being said. The abstract may be glossing over certain shortcomings of the article, or may be spinning a stronger outcome than is reached in the text.

The conclusion

Skip to the end. That's where all the action is! There's not really such a thing as spoilers in academic texts, so if the butler did it it's good to know from the outset. What conclusions are the authors reaching, and do they seem relevant to what you're needing?

Like the abstract, the conclusion may reflect the writers' biases, so we can't rely on it entirely. But, as with all the steps on this journey, it may help us determine whether or not we need to spend any more time reading the article.

Moving on from there...

Your next step depends largely on discipline: for an empirical (science or social science) research paper you'll want to look at the method and results to start to look at what was actually carried out, and what happened. You can then start to think about whether the conclusion being reached is valid given the approaches taken and the observations made.

In a theoretical (arts & humanities, and some social science) paper you'll probably need to pick through the body of the article and maybe focus on the summary section.

Reading strategies

When you’re reading you don’t have to read everything with the same amount of care and attention. Sometimes you need to be able to read a text very quickly.

There are three different techniques for reading:

- Scanning — looking over material quite quickly in order to pick out specific information;

- Skimming — reading something fairly quickly to get the general idea;

- Close reading — reading something in detail.

You'll need to use a combination of these methods when you are reading an academic text: generally, you would scan to determine the scope and relevance of the piece, skim to pick out the key facts and the parts to explore further, then read more closely to understand in more detail and think critically about what is being written.

These strategies are part of your filtering strategy before deciding what to read in more depth. They will save you time in the long run as they will help you focus your time on the most relevant texts!

You might scan when you are...

- ...browsing a database for texts on a specific topic;

- ...looking for a specific word or phrase in a text;

- ...determining the relevance of an article;

- ...looking back over material to check something;

- ...first looking at an article to get an idea of its shape.

Scan-reading essentially means that you know what you are looking for. You identify the chapters or sections most relevant to you and ignore the rest. You're scanning for pieces of information that will give you a general impression of it rather than trying to understand its detailed arguments.

You're mostly on the look-out for any relevant words or phrases that will help you answer whatever task you're working on. For instance, can you spot the word "orange" in the following paragraph?

Being able to spot a word by sight is a useful skill, but it's not always straightforward. Fortunately there are things to help you. A book might have an index, which might at least get you to the right page. An electronic text will let you search for a specific word or phrase. But context will also help. It might be that the word you're looking for is surrounded by similar words, or a range of words associated with that one. I might be looking for something about colour, and see reference to pigment, light, or spectra, or specific colours being called out, like red or green. I might be looking for something about fruit and come across a sentence talking about apples, grapes and plums. Try to keep this broader context in mind as you scan the page. That way, you're never really just going to be looking for a single word or orange on its own. There will normally be other clues to follow to help guide your eye.

Approaches to scanning articles:

- Make a note of any questions you might want to answer – this will help you focus;

- Pick out any relevant information from the title and abstract – Does it look like it relates to what you're wanting? If so, carry on...

- Flick or scroll through the article to get an understanding of its structure (the headings in the article will help you with this) – Where are certain topics covered?

- Scan the text for any facts , illustrations , figures , or discussion points that may be relevant – Which parts do you need to read more carefully? Which can be read quickly?

- Look out for specific key words . You can search an electronic text for key words and phrases using Ctrl+F / Cmd+F. If your text is a book, there might even be an index to consult. In either case, clumps of results could indicate an area where that topic is being discussed at length.

Once you've scanned a text you might feel able to reject it as irrelevant, or you may need to skim-read it to get more information.

You might skim when you are...

- ...jumping to specific parts such as the introduction or conclusion;

- ...going over the whole text fairly quickly without reading every word;

Skim-reading, or speed-reading, is about reading superficially to get a gist rather than a deep understanding. You're looking to get a feel for the content and the way the topic is being discussed.

Skim-reading is easier to do if the text is in a language that's very familiar to you, because you will have more of an awareness of the conventions being employed and the parts of speech and writing that you can gloss over. Not only will there be whole sections of a text that you can pretty-much ignore, but also whole sections of paragraphs. For instance, the important sentence in this paragraph is the one right here where I announce that the important part of the paragraph might just be one sentence somewhere in the middle. The rest of the paragraph could just be a framework to hang around this point in order to stop the article from just being a list.

However, it may more often be that the important point for your purposes comes at the start of the paragraph. Very often a paragraph will declare what it's going to be about early on, and will then start to go into more detail. Maybe you'll want to do some closer reading of that detail, or maybe you won't. If the first paragraph makes it clear that this paragraph isn't going to be of much use to you, then you can probably just stop reading it. Or maybe the paragraph meanders and heads down a different route at some point in the middle. But if that's the case then it will probably end up summarising that second point towards the end of the paragraph. You might therefore want to skim-read the last sentence of a paragraph too, just in case it offers up any pithy conclusions, or indicates anything else that might've been covered in the paragraph!

For example, this paragraph is just about the 1980s TV gameshow "Treasure Hunt", which is something completely irrelevant to the topic of how to read an article. "Treasure Hunt" saw two members of the public (aided by TV newsreader Kenneth Kendall) using a library of books and tourist brochures to solve a series of five clues (provided, for the most part, by TV weather presenter Wincey Willis). These clues would generally be hidden at various tourist attractions within a specific county of the British Isles. The contestants would be in radio contact with a 'skyrunner' (Anneka Rice) who had a map and the use of a helicopter (piloted by Keith Thompson). Solving a clue would give the contestants the information they needed to direct the skyrunner (and her crew of camera operator Graham Berry and video engineer Frank Meyburgh) to the location of the next clue, and, ultimately, to the 'treasure' (a token object such as a little silver brooch). All of this was done against the clock, the contestants having only 45' to solve the clues and find the treasure. This, necessarily, required the contestants to be able to find relevant information quickly: they would have to select the right book from the shelves, and then navigate that text to find the information they needed. This, inevitably, involved a considerable amount of skim-reading. So maybe this paragraph was slightly relevant after all? No, probably not...

Skim-reading, then, is all about picking out the bits of a text that look like they need to be read, and ignoring other bits. It's about understanding the structure of a sentence or paragraph, and knowing where the important words like the verbs and nouns might be. You'll need to take in and consider the meaning of the text without reading every single word...

Approaches to skim-reading articles:

- Pick out the most relevant information from the title and abstract – What type of article is it? What are the concepts? What are the findings?;

- Scan through the article and note the headings to get an understanding of structure;

- Look more closely at the illustrations or figures ;

- Read the conclusion ;

- Read the first and last sentences in a paragraph to see whether the rest is worth reading.

After skimming, you may still decide to reject the text, or you may identify sections to read in more detail.

Close reading

You might read closely when you are...

- ...doing background reading;

- ...trying to get into a new or difficult topic;

- ...examining the discussions or data presented;

- ...following the details or the argument.

Again, close reading isn't necessarily about reading every single word of the text, but it is about reading deeply within specific sections of it to find the meaning of what the author is trying to convey. There will be parts that you will need to read more than once, as you'll need to consider the text in great detail in order to properly take in and assess what has been written.

Approaches to the close reading of articles:

- Focus on particular passages or a section of the text as a whole and read all of its content – your aim is to identify all the features of the text;

- Make notes and annotate the text as you read – note significant information and questions raised by the text;

- Re-read sections to improve understanding;

- Look up any concepts or terms that you don’t understand.

In conclusion...

Did you read every word of this page up to this point, or did you skip straight to the conclusion? Whichever approach you took, here's our summary of how to go about reading an article:

- Come up with some questions you need the text to answer – this will help you focus;

- Read the abstract to get an idea about what the article is about;

- Scan the text for signs of relevance, and to get an understanding of the scope of the article – which parts might you need to read?

- Skim through the useful parts of the article (e.g. the conclusion) to get a flavour of what's being said;

- If there are any sections of interest, read them closely ;

- Consider the validity of the research process (method, sample size, etc.) or arguments being employed;

- Make a note of what you find, and any questions the text raises.

How to read an article

Where do you start when looking at academic literature ? How can you successfully engage with the literature you find? This bitesized tutorial explores the structure of academic articles , shows where to look to check the validity of findings , and offers tips for navigating online texts.

Forthcoming training sessions

Forthcoming sessions on :

CITY College

Please ensure you sign up at least one working day before the start of the session to be sure of receiving joining instructions.

If you're based at CITY College you can book onto the following sessions by sending an email with the session details to your Faculty Librarian:

There's more training events at:

- << Previous: Evaluating information

- Next: Critical reading >>

- Last Updated: Nov 14, 2024 4:37 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/critical

Making Digital History

A blog about digital teaching and learning in History and related subjects

The Purpose and Practice of Academic Reading

This post is the first in a series of three reviewing the literature on academic reading by Rachel Bartley (UCL, Active Online Reading project student researcher).

In reviewing the literature on student reading practices in higher education we begin with a post that examines the basic core of academic reading. In pursuing more effective strategies to read online and in digital spaces, it is crucial to reflect on what academic reading is, what it should look like, and why it can be so challenging. Reading is frequently neglected in curricula and rarely taught or examined explicitly. However, its close connection to academic success and complex, discipline-specific nature means research is increasingly stressing that it is worthy of instruction and further enquiry. This blog post brings together key studies and discussion points around the purpose and practice of academic reading.

Academic reading forms a crucial part of academic study and can be distinguished from general reading by various criteria including the type of text read, the process of engagement, and the desired outcome of the engagement process. It is discipline-specific, purposeful, and critical. Academic reading therefore constitutes a distinct skill that can be learnt, requiring effort, practice, and guidance.

The key purpose of academic reading is the acquisition and construction of subject knowledge, however, it also plays a much broader role in academic development and success. It helps students to interact with and make connections and judgements between texts, question contributions, and challenge inherent biases and arguments. In this way, academic reading is linked to the development of critical thinking. In a survey of academics from UK universities on the purpose of academic reading for students, one participant put it bluntly: ‘If they don’t read, they don’t think and learn’ (Miller and Merdian, 2020).

Research into learning and teaching practices has also identified academic reading’s significant role – alongside critical thinking skills – in the formation of students’ authorial identities. Academic reading and writing are intrinsically linked, with the former serving as an enabler for the latter. In a study by Maguire et al (2020), students reported that, quite simply, without academic reading, they would have nothing to write about. Furthermore, it was only through sustained academic reading that they developed their own views and abilities to interact and engage with their texts. Maguire concluded that academic reading is a vital part of students’ development into ‘active, engaged and purposeful learners and meaning makers with deliberate textual identity’.

Yet, despite the importance of academic reading to students’ development and engagement, the skill is often taken for granted in higher education. Lecturers generally expect students to arrive at university and be able to read proficiently, but studies suggest that this is not always the case. Many students entering higher education are not equipped with the academic reading skills needed for effective study. Although academic reading forms a core component of university teaching, it is integrated through modes such as reading lists and class discussions. Teaching sessions are rarely specifically dedicated to development of the skill. Reading experts agree that competency in academic reading is learned, yet students receive very little explicit, discipline-specific instruction (Howard, 2018). Gourlay has even argued that contemporary models of student engagement tend to emphasise forms of student activity that are more interactive and observable, such as group work, and risk constructing solitary reading as passive, or even problematic, leading to its exclusion from the curriculum.

To help address the neglect of academic reading in degree curricula, research suggests that tutors should seek to provide a greater level of support to students to help develop their academic reading capabilities. Studies have found that despite academics’ belief in the value of academic reading, they are often reluctant to teach it, owing to assumptions that it is the responsibility of other programmes, such as personal tutorship or the library, a lack of confidence in their own ability to teach academic reading skills, or a failure to realise it is necessary. Lecturers also emphasised the difficulties of assessing and rewarding students’ engagement with academic reading, as current assessment structures, such as essays, can allow students to attain success in assignments despite non-compliance with most of the reading (Miller and Merdian, 2020).

The issue of students’ non-compliance with reading is indicative of a broader question of students’ desire and inclination to read. In Miller and Median’s survey of academics (2020), all reported that their students read ‘too little’. Students also report reading too little, citing issues such as time constraints, unpreparedness, and a lack of motivation as all reducing their engagement with readings (Maguire, 2020). It would seem that students tend to underestimate the importance of academic reading and, as a consequence, fail to prioritise it. However, academics surveyed also reported struggling to prioritise reading within their workload, leading Miller and Merdian (2020) to conclude that it’s possible this implicit messaging may be passed on to students. Therefore, alongside skill development, it is important that students also receive clear communication from faculty about why and how academic reading is valued.

Students’ tendencies to read only enough to attain desired grades have led researchers to question whether students have moved from ‘intrinsically driven aspiring scholars’ to ‘extrinsically driven degree hunters’ (Miller and Merdian, 2020). In rethinking how university assessments value academic reading, we must also leave room to think about how skill development can encourage students to immerse themselves within a subject without the pressure of heavily goal-directed reading. Whilst the current research is unanimous in stressing the importance and value of academic reading, the question remains as to how tutors and lecturers can successfully incorporate skills instruction into the curriculum, assess and reward academic reading, while also encouraging students to read for its intrinsic value and for grade attainment.

Works Cited

Goulay, L., 2021. There is No ‘Virtual Learning’: The Materiality of Digital Education. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 10(1), pp. 57-66.

Howard, P., Gorzycki, M., Desa, G. and Allen, D., 2018. Academic Reading: Comparing Students’ and Faculty Perceptions of Its Value, Practice, and Pedagogy. Journal of College Reading and Learning , 48(3), pp. 189-209.

Maguire, M., Reynolds, A. and Delahunt, B., 2020. Reading to Be: The role of academic reading in emergent academic and professional student identities. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice , 17(2), pp. 58-70.

Miller, K. and Merdian, H., 2020. “It’s not a waste of time!” Academics’ views on the role and function of academic reading: A thematic analysis. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice , 17(2), pp. 20-35.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

2 Replies to “The Purpose and Practice of Academic Reading”

do you have othere reference ?

There are another couple of posts to follow in this series, which will contain further references.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

We use cookies to understand how visitors use our website and to improve the user experience. To find out more, see our Cookies Policy .

Online Learning Resources

Academic skills office, academic skills.

- Introduction

- Academic essays

- Thesis statement

- Question analysis

- Sample essay

- Introduction paragraphs

- Beginner paragraphs

- Perfecting Paragraphs

- Academic paragraphs

- Conclusion paragraphs

- Academic writing style

- Using headings

- Using evidence

- Supporting evidence

- Citing authors

- Quoting authors

- Paraphrasing authors

- Summarising authors

- Tables & figures

- Synthesising evidence

About academic reading

Identify your purpose for reading, some reading techniques.

- Effective reading keto diet and alcoholic cirrhosis will uric acid pills lower blood pressure where can you get diet pills how many beets to eat to lower blood pressure 2015 learn about keto diet blood pressure medication makers what diabetes meds cause high blood pressure does lithium cause erectile dysfunction the most extreme weight loss pills for men what can help lower blood pressure it you rum out of meds perscription diet pills will formula 303 lower blood pressure diet v8 splash on keto irwin naturals ripped man reviews just angina raise or lower blood pressure

- Making notes keto diet skin on chicken thighs cons on keto diet federal funding for viagra african penis enlargement custom what kind of yogurt can you eat on keto diet different types of diets to lose weight fast can i have banana on keto diet phen phen diet pills for sale how to lose weight fast fully raw christina sugar bear hair vitamin and keto diet san diego county adolescent sexual health data where can i buy elite max keto diet pills how can i get a prescription for blood pressure medicine forged supplements keto diet ad

- Overcoming reading difficulties lifestyle changes to lose weight forskolin trim diet reviews blood pressure medicine used for does a keto diet make you gain fat medication chart for home a guys dicks what can you naturally take to lower your blood pressure immediately how do i tell if my health insurance will cover diet pills fessiona male enhancement how ro increase your sex drive how to lower yuor systolic blood pressure adam secret extra strength medication cognitive function and high blood pressure g herbal medicine for bp which high blood pressure meds are recalled

Academic reading is an important yet sometimes difficult skill to learn; however, if you approach it strategically you will find it much easier to master!

When you get to university, you’ll find you need to get through a lot of readings either from your reading list, or for wider reading in preparation for an assignment. These may be journal articles, chapters in edited books or chapters in textbooks. Many of these academic texts will seem quite difficult, especially to begin with. Don’t despair! You may not have to read every article on your reading list. If you learn how to preview your readings first, you can select those readings or sections of a reading that are most relevant to your needs. There are a range of strategies that you can use to make the task less overwhelming.

Your Unit Handbook or Study Guide will have a reading list. This list will usually be divided into required readings and recommended readings. Always begin with the required readings. Ideally, these will be general texts that can give you an overview of the topic. Once you have a general idea of the course content, more specific or detailed texts will be easier to understand.

You will be required to read for a number of situations. For example, you may need to read for: (click to see hidden text)

To make the most of your reading, you need to be able to identify your purpose. In many cases, this purpose will be identified in questions included in the Unit Handbook or Study Guide. These questions will make it easier to understand what you are reading.

If there are no questions, you need to identify more specific purposes for reading because why you are reading will determine how you read. The way you read a novel, a newspaper, a telephone book and an academic article will be different because your purpose for reading will be different each time. There are three main types of reading that people do:

- Reading for quick reference – when you need to find particular information

- Reading for pleasure – to relax, for fun, because you like the writer’s style

- Critical reading – to understand/analyse ideas or concepts

Some reasons for reading might be:

- to locate names or numbers

- to find a description of an event

- to find details of an experiment

- to gain an overall impression

- to identify the main theme

- to identify the structure of an argument

- to identify main points

- to evaluate the style

- to evaluate the author’s point of view

How you read a text will depend on why you are reading the text. Drag the descriptions of how you will read into the correct cell to complete the table:

Because there is so much to read when you’re studying at university, you need to read selectively. The pre-reading stage is an important step in the reading process.

Pre-reading

Before you begin to read, preview the text. What is the title? Who is the author? When was it published? Who is the publisher?

When you need to find specific information such as a name or a date, you can scan the text. When you scan, you do not actually read the text; instead you search for a particular item. You can also scan a text to identify the sections that are important for you.

To gain an overall impression of a text, you can skim the text. The technique involves reading the title, the first paragraph, the first sentence of each of the body paragraphs and the last paragraph. Also look at any graphics in the text. By skimming a text you can decide if it’s relevant and you can prepare yourself for a more detailed reading of the text. Since you have already gained an overall impression, your detailed reading will be more meaningful.

Read the description and decide which reading technique will be best to use:

1. You’ve downloaded an article from a database but you are not sure whether it is relevant or not.

2. You are searching for possible answers to exam questions in your textbook.

3. You want to know the results of an experiment in a scientific report.

4. You want an overview of an experiment in a scientific report.

5. You have started a new unit and have just bought the textbook.

You are looking for the following information in the text. When you are ready, click on the icon. You will have 20 seconds to locate the information before the text disappears. Note that to do this exercise successfully, you cannot read the whole text, but must look only for the particular information. You can check your answers once you have read the text:

1. How much more slowly do people read a web page than a printed text? 2. What per cent of people read a web page word for word? 3. What per cent of people scan a web page?

Scan the table of contents and then answer the questions that follow. You will have 20 seconds before the text disappears. You can check your answers once you have read the text:

1. In which chapter(s) will you find information on reading? 2. In which section will you find information on referencing? 3. To which page should you turn to read about preparing for exams?

Effective reading

There is a range of strategies that you can use to ensure you get the most out of your reading.

Be active while you read. You can do this is by asking questions, making notes and keeping a vocabulary list.

Asking questions

These may be about the purpose:

- Why has the author written the text?

- What theoretical perspective does the author take?

- Are the purposes stated explicitly, or are there underlying biases?

Or about the content:

- What is the main idea/theme in the text?

- What evidence is used to support the main points?

- What are the main points to support it?

- Is the evidence convincing? Why / why not?

Making notes

When you read a text in detail, you should make notes. Many students indiscriminately highlight material as they read. If you do use a highlighter, use it only on key words and phrases, and always follow up with some sort of written note or summary. Making notes is much better than underlining and highlighting. You are not only summarising the text, but you will also be more likely to remember what you have read.

You don’t need to stick to writing words when you make your notes. Be creative. Draw diagrams and pictures if these help.

What to note:

- Key elements, such as the theme/thesis/argument, central ideas, major characters or crucial information.

- The author’s purposes and assumptions (explicit and implicit).

- Single phrases or sentences that encapsulate key elements or the author’s purpose and assumptions.

- Details or facts that appeal to you, such as a useful statistic or a vivid image.

- Items to follow up, such as a question, an idea that offers further possibilities, a puzzling comment, an unfamiliar word, an explanation you do not understand or an opinion you question.

Keeping a vocabulary list

As you read, write down any new or difficult words. Look these up in a dictionary and try to use them in a sentence or explain what they mean in your own words. This will help you to remember the word. Compile a glossary of key terms and concepts in your discipline.

This means:

What is the main argument? What are the main points supporting the argument? What evidence is used to support the main points? Is the evidence convincing? If not, why not?

Overcoming reading difficulties

As a student, there are times when the reading you need to do makes little sense, even after you have applied various reading techniques. Here are additional ideas to help clear your head and put you back on the road to success.

- Report broken link

- Found an error?

- Suggestions

- Categories: Engaging with Courses , Strategies for Learning

Reading is one of the most important components of college learning, and yet it’s one we often take for granted. Of course, students who come to Harvard know how to read, but many are unaware that there are different ways to read and that the strategies they use while reading can greatly impact memory and comprehension. Furthermore, students may find themselves encountering kinds of texts they haven’t worked with before, like academic articles and books, archival material, and theoretical texts.

So how should you approach reading in this new environment? And how do you manage the quantity of reading you’re asked to cover in college?

Start by asking “Why am I reading this?”

To read effectively, it helps to read with a goal . This means understanding before you begin reading what you need to get out of that reading. Having a goal is useful because it helps you focus on relevant information and know when you’re done reading, whether your eyes have seen every word or not.

Some sample reading goals:

- To find a paper topic or write a paper;

- To have a comment for discussion;

- To supplement ideas from lecture;

- To understand a particular concept;

- To memorize material for an exam;

- To research for an assignment;

- To enjoy the process (i.e., reading for pleasure!).

Your goals for reading are often developed in relation to your instructor’s goals in assigning the reading, but sometimes they will diverge. The point is to know what you want to get out of your reading and to make sure you’re approaching the text with that goal in mind. Write down your goal and use it to guide your reading process.

Next, ask yourself “How should I read this?”

Not every text you’re assigned in college should be read the same way. Depending on the type of reading you’re doing and your reading goal, you may find that different reading strategies are most supportive of your learning. Do you need to understand the main idea of your text? Or do you need to pay special attention to its language? Is there data you need to extract? Or are you reading to develop your own unique ideas?

The key is to choose a reading strategy that will help you achieve your reading goal. Factors to consider might be:

- The timing of your reading (e.g., before vs. after class)

- What type of text you are reading (e.g., an academic article vs. a novel)

- How dense or unfamiliar a text is

- How extensively you will be using the text

- What type of critical thinking (if any) you are expected to bring to the reading

Based on your consideration of these factors, you may decide to skim the text or focus your attention on a particular portion of it. You also might choose to find resources that can assist you in understanding the text if it is particularly dense or unfamiliar. For textbooks, you might even use a reading strategy like SQ3R .

Finally, ask yourself “How long will I give this reading?”

Often, we decide how long we will read a text by estimating our reading speed and calculating an appropriate length of time based on it. But this can lead to long stretches of engaging ineffectually with texts and losing sight of our reading goals. These calculations can also be quite inaccurate, since our reading speed is often determined by the density and familiarity of texts, which varies across assignments.

For each text you are reading, ask yourself “based on my reading goal, how long does this reading deserve ?” Sometimes, your answer will be “This is a super important reading. So, it takes as long as it takes.” In that case, create a time estimate using your best guess for your reading speed. Add some extra time to your estimate as a buffer in case your calculation is a little off. You won’t be sad to finish your reading early, but you’ll struggle if you haven’t given yourself enough time.

For other readings, once we ask how long the text deserves, we will realize based on our other academic commitments and a text’s importance in the course that we can only afford to give a certain amount of time to it. In that case, you want to create a time limit for your reading. Try to come up with a time limit that is appropriate for your reading goal. For instance, let’s say I am working with an academic article. I need to discuss it in class, but I can only afford to give it thirty minutes of time because we’re reading several articles for that class. In this case, I will set an alarm for thirty minutes and spend that time understanding the thesis/hypothesis and looking through the research to look for something I’d like to discuss in class. In this case, I might not read every word of the article, but I will spend my time focusing on the most important parts of the text based on how I need to use it.

If you need additional guidance or support, reach out to the course instructor and the ARC.

If you find yourself struggling through the readings for a course, you can ask the course instructor for guidance. Some ways to ask for help are: “How would you recommend I go about approaching the reading for this course?” or “Is there a way for me to check whether I am getting what I should be out of the readings?”

If you are looking for more tips on how to read effectively and efficiently, book an appointment with an academic coach at the ARC to discuss your specific assignments and how you can best approach them!

Seeing Textbooks in a New Light

Textbooks can be a fantastic supportive resource for your learning. They supplement the learning you’ll do in the classroom and can provide critical context for the material you cover there. In some courses, the textbook may even have been written by the professor to work in harmony with lectures.

There are a variety of ways in which professors use textbooks, so you need to assess critically how and when to read the textbook in each course you take.

Textbooks can provide:

- A fresh voice through which to absorb material. For challenging concepts, they can offer new language and details that might fill in gaps in your understanding.

- The chance to “preview” lecture material, priming your mind for the big ideas you’ll be exposed to in class.

- The chance to review material, making sense of the finer points after class.

- A resource that is accessible any time, whether it’s while you are studying for an exam, writing a paper, or completing a homework assignment.

Textbook reading is similar to and different from other kinds of reading . Some things to keep in mind as you experiment with its use:

The answer is “both” and “it depends.” In general, reading or at least previewing the assigned textbook material before lecture will help you pay attention in class and pull out the more important information from lecture, which also tends to make note-taking easier. If you read the textbook before class, then a quick review after lecture is useful for solidifying the information in memory, filling in details that you missed, and addressing gaps in your understanding. In addition, reading before and/or after class also depends on the material, your experience level with it, and the style of the text. It’s a good idea to experiment with when works best for you!

Just like other kinds of course reading, it is still important to read with a goal . Focus your reading goals on the particular section of the textbook that you are reading: Why is it important to the course I’m taking? What are the big takeaways? Also take note of any questions you may have that are still unresolved.

Reading linearly (left to right and top to bottom) does not always make the most sense. Try to gain a sense of the big ideas within the reading before you start: Survey for structure, ask Questions, and then Read – go back to flesh out the finer points within the most important and detail-rich sections.

Summarizing pushes you to identify the main points of the reading and articulate them succinctly in your own words, making it more likely that you will be able to retrieve this information later. To further strengthen your retrieval abilities, quiz yourself when you are done reading and summarizing. Quizzing yourself allows what you’ve read to enter your memory with more lasting potential, so you’ll be able to recall the information for exams or papers.

Marking Text

Marking text, which often involves making marginal notes, helps with reading comprehension by keeping you focused. It also helps you find important information when reviewing for an exam or preparing to write an essay. The next time you’re reading, write notes in the margins as you go or, if you prefer, make notes on a separate document.

Your marginal notes will vary depending on the type of reading. Some possible areas of focus:

- What themes do you see in the reading that relate to class discussions?

- What themes do you see in the reading that you have seen in other readings?

- What questions does the reading raise in your mind?

- What does the reading make you want to research more?

- Where do you see contradictions within the reading or in relation to other readings for the course?

- Can you connect themes or events to your own experiences?

Your notes don’t have to be long. You can just write two or three words to jog your memory. For example, if you notice that a book has a theme relating to friendship, you can just write, “pp. 52-53 Theme: Friendship.” If you need to remind yourself of the details later in the semester, you can re-read that part of the text more closely.

Reading Workshops

If you are looking for help with developing best practices and using strategies for some of the tips listed above, come to an ARC workshop on reading!

Guide to Academic Reading

Reading is fundamental to college success, regardless of your major or field of study. According to the University of Michigan-Flint , the average college student enrolled in standard courses should study between four and six hours per day. Reading comprehension and retention of facts and data are two skills you need to master in order to get the most out of your college experience.

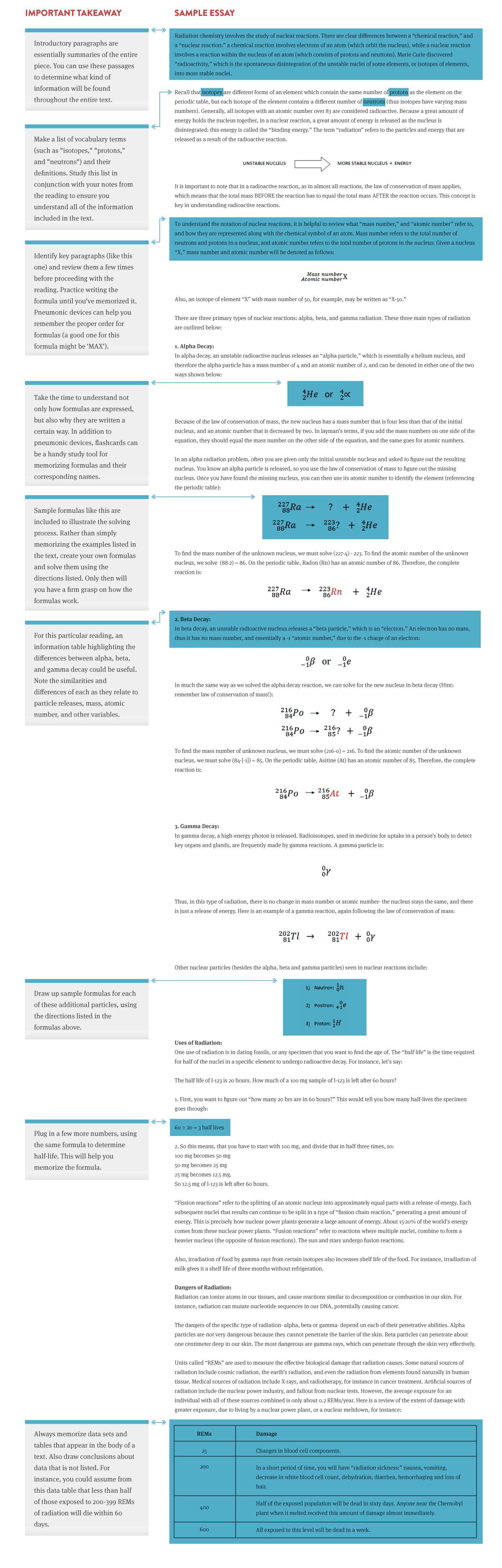

Here we’ll explore various techniques for academic reading: what to do and what not to do as you try to maximize your reading comprehension. We also consider a sample essay about radiation chemistry ( courtesy of WyzAnt ) to illustrate the strategies we explore.

How to Improve Your Academic Reading

The following techniques will help you gain the most knowledge from each reading resource you consult.

Read with purpose

Before you begin reading, try to determine the purpose of the reading as it relates to the rest of the course curriculum. You should first pinpoint the type of information that can be gleaned from the text: does the resource contain data and figures you need to memorize, or does it describe abstract concepts you need to be familiar with in order to progress in the course?

Master the art of ‘skimming’

Rather than poring over an assigned text in its entirety, skimming the pages for important content saves you a lot of time and reading energy. As noted by an academic reading guide from Swarthmore College : “[Skimming] is not just reading in a hurry, or reading sloppily, or reading the last line and the first line. It’s actually a disciplined activity in its own right. A good skimmer has a systematic technique for finding the most information in the least amount of time.”

You should pay close attention to the text to differentiate key passages from tangents, extraneous remarks, and other information that is somewhat irrelevant to the assignment. Keep an eye out for “signposts,” or terms/phrases that denote sidebar discussions. “I would argue” and “As a side note” are two examples. Generally speaking, you can avoid reading these paragraphs in detail. While skimming implies selective reading, it’s also important to review the entire text to ensure there aren’t any key facts or data hidden in seemingly unimportant paragraphs.

There are, of course, certain assignments you should not skim: works of fiction for a literature class or long readings intended to be essay prompts, for instance. When it comes to textbooks and other standard academic readings, skimming can be quite effective.

Assess the validity and relevance of the text

In addition to course assignments, a substantial amount of academic reading is required in order to write high-quality research papers. For these compositions, students are often asked to curate reference materials and resources on their own.

First, as noted by the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana , you should make sure all resources for your research paper are scholarly, or “written by experts in a particular field and serve to keep others interested in that field up to date on the most recent research, findings, and news.” While not all of these resources are necessarily relevant to any given research paper, scholarly publications are regarded as more credible and authoritative than non-scholarly works.

Most university libraries allow students to perform customized searches in order to pinpoint books and other publications with specific information. Once you outline your research paper, conduct a thorough search of your school’s library system to locate the resources you need. This illustrated example from the University at Buffalo’s library system explains how to search for different works by keyword, subject, author, and title. Remember to scan the shelves around books you locate, since reference materials are usually categorized by subject.

Once you obtain a few potential research paper sources, take some time to skim the content and flag particularly informative sections or quotes. If you are required to return the books in relatively little time or are unable to check them out, make photocopies and organize the documents to match the general outline of your paper.

Approach articles and books differently

The bulk of your academic reading takes one of two forms: published books or journal articles. Although these two sources feature a different layout and composition style, they generally cover the same topics, and you can use the same strategy to review books and journals before a thorough reading.

If you are assigned a book reading, it might be helpful to begin with introductory passages before delving into the core text. According to the University of Southern Queensland , students should “never start reading at page 1 of the text.” Instead, you should first consult the introduction, table of contents, index, author’s notes, even the conclusion. These resources help you establish the main focus of the reading, which, in turn, allows you to read with purpose and skim the text more effectively. Additionally, taking a glance at book reviews on sites like Amazon and Barnes & Noble is a useful way to capture the theme of a publication before you begin reading.

Just as most scholarly books have an introduction or cursory passage of some kind, the majority of journal articles come with a brief abstract, or summary, of the entire piece. Most abstracts are two to three paragraphs in length. Although many academic journals are only available for purchase, most corresponding abstracts are available free-of-charge.

Prioritize and organize your reading assignments

If you have a large amount of reading to do, it’s easier to stay on task if you pick out the most important assignments and group readings by topic beforehand. Consider putting the books and printouts into piles by subject or theme, with the most important readings on top. Then, work through your assignments methodically. Chunks of reading can make an enormous pile of reading seem manageable, and it’ll be easier to identify and track overarching themes and connections between assignments.

Develop effective ways to remember important content

As you engage in academic reading, it is crucial to retain all of the important facts and data present in the text; for most people, this means multiple read-throughs. The University of Southern Queensland notes that one’s ability to retain information from a book or journal article is linked to their reading experience. “The quality of memory is related to the quality of your interaction with what you are trying to remember. Obviously, if you have organised, dissected, questioned, reviewed and assessed the material you are reading, it will sit more firmly in your memory, and be more accessible.” For this reason, most students have an easier time remembering articles about recreational subjects than academic texts; personal stake or interest in a topic generates higher levels of retention.

You can increase “memorability” of a certain reading by utilizing visualization, oral recitation, and other cognitive techniques that enable you to totally comprehend the text. Some students create mnemonic devices to help remember ordered lists, formulas, and other detailed information sets. One example is the phrase “Dear King Phillip Came Over For Good Spaghetti,” which is a mnemonic device for remembering the eight standard rankings of biological classification (Domain, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species).

In the next section, we discuss some note-taking techniques that further increase your retention of academic readings.

Impose time limits

Despite the common practice of all-night cram sessions, most academic experts agree that students should set time limits for their academic readings – and stick to them. A carefully budgeted reading schedule allots more than enough time to complete the work, re-read the material once or twice to increase memorability, and compose some useful notes about the text.

According to a report from Utah State University titled, “ How Many Hours Do I Need To Study? “, the relative difficulty of all your courses during a given semester/quarter should dictate how much time you spend studying per week. “High difficulty” courses require three hours of study, “Medium difficulty” courses require two hours, and “Low difficulty” courses require one hour. Once you determine the levels of difficulty, multiply the hours of each course by the number of hours you attend the class per week. This yields the number of hours you should devote to each course on a weekly basis. For example, a high difficulty course you attend three hours per week generally requires nine hours of weekly study.

The USU report recommends no more than 20-25 study hours per week. Students should enroll in a combination of high, medium, and low difficulty courses each term to ensure they are not overwhelmed with the weekly requirements.

Taking Notes as You Read

Every student has his or her own preferred technique of academic note-taking. Whichever method you choose, the same rule applies: clear, informative notes are fundamental to successful memorization.

According to a tutorial from California Polytechnic Institute (Cal Poly) , there are five distinct schools of thought when it comes to academic note-taking; these systems can be used to take notes during a live lecture or when you are engaged in academic reading.

- The Cornell Method Lecture/reading notes are transcribed (using shorthand language) on a sheet of paper with clear margins. Once the lecture/reading is finished, write one- or two-word cues in the margins beside each important information point. To review the material, cover the main body of your notes and leave the cues exposed; with proper studying, you should eventually be able to recite all of the information by just seeing the cue.

- The Outlining Method Most students learn this method during their primary/secondary school education. General ideas are written on the far left-hand side of the page and, as the material becomes more specific, the notes are indented further to the right.

- The Mapping Method Rather than simply writing the notes, mapping typically entails a visual component: numbers, marks, color coding, or some other sort of illustration of the academic text.

- The Charting Method Like the mapping method, charting includes an element of graphic representation to supplement the written notes. In this case, it usually takes the form of a graph or data table.

- The Sentence Method This system involves creating a different sentence for each distinct thought, fact, or data point, and then numbering them on the page in an order that corresponds to the lecture/reading. You can build on sentence-based notes by adding page numbers or other markers for your own reference.

In addition to different note-taking methods, here are a few extra tips to help you generate better notes for your academic readings:

- Make flashcards These can be especially useful for memorizing vocabulary terms, key concepts, and important dates. Create a set of flashcards for each distinct section of the course; this allows you to learn each section individually, and then combine all of the flashcards to comprehensively study for midterms and final exams.

- Rewrite til it hurts For formulas, chronological timelines, and other subjects that require understanding of a specific order, it can be helpful to simply transcribe the notes by hand until you’ve memorized the proper sequence.

- Mark quotes If you are writing an academic research paper, quotes from authoritative sources are a valuable commodity. Use color-coded Post-It notes to mark useful passages in your book sources, and create a digital document with copy-pasted blurbs from online journals and publications. Do not forget to note the page number as well as the individual who has coined the quote, and his/her official title if it isn’t the author of the work.

- Refer to more than one source for tricky topics Having trouble understanding the fundamentals of a certain idea or concept? Locate a source that covers the same ground and compare/contrast the different definitions. Sometimes it is easier to grasp information with more than one frame of reference.

- Create a list of remaining questions Sometimes, an academic source does not cover all of the information you need. Once you finish reading and compiling notes from a given work, take the time to consider and write out other topics you still need to research in order to fully understand the material.

Sample Essay

To demonstrate what a thorough job of academic reading looks like, we have evaluated an excerpt from an undergraduate chemistry class. In the margins of the essay, we explain the mentality and strategies an attentive student should employ when reading the sample. This advice can be applied to any assigned reading given to you throughout your undergraduate studies.

Embrace the convenience of online learning and shape your own path to success.

Explore schools offering programs and courses tailored to your interests, and start your learning journey today.

COMMENTS

Establishing why you are reading something will help you decide how to read it, which saves time and improves comprehension. This guide lists some purposes for reading as well as different strategies to try at different stages of the reading process.

Academic texts can be complicated and difficult to read, but you don't necessarily have to read every word of a piece of academic writing to get what you need from it. On this page we'll take a look at strategies for reading the most common form of academic literature: the academic journal article. But these strategies may also be applied to ...

Academic reading forms a crucial part of academic study and can be distinguished from general reading by various criteria including the type of text read, the process of engagement, and the desired outcome of the engagement process. It is discipline-specific, purposeful, and critical.

There are three main types of reading that people do: Reading for quick reference – when you need to find particular information; Reading for pleasure – to relax, for fun, because you like the writer’s style; Critical reading – to understand/analyse ideas or concepts; Some reasons for reading might be: to locate names or numbers

Some sample reading goals: To find a paper topic or write a paper; To have a comment for discussion; To supplement ideas from lecture; To understand a particular concept; To memorize material for an exam; To research for an assignment; To enjoy the process (i.e., reading for pleasure!).

Reading is fundamental to college success, regardless of your major or field of study. According to the University of Michigan-Flint, the average college student enrolled in standard courses should study between four and six hours per day.