- Emergency information

- Increase Font Size

- Decrease Font Size

Critical care nursing education

The Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN) has developed an online course Core Critical Care Nursing This short course has been designed for nurses as a rapid introduction to Critical Care.

- The course is free.

- Participants must register to access the course.

- Participants will need to know their AHPRA Registration number to access the modules.

- Once the participant has registered and completed the modules they will receive a certificate for their Professional Development records.

Course units

Chapter 1 - basic nursing care.

- Nursing Care of the Mechanically Ventilated Patient

- Top 10 Tips to Recognise and Respond to Patient Deterioration

- Nursing Management of Critically Ill Patients with a Central Venous Catheter

Chapter 2 – Mechanical Ventilation

- Mechanical Ventilation

- CPAP and PEEP

- Common Drugs Used in Sedation Protocols in Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Chapter 3 – Cardiovascular

- Introduction to ECG Rhythm Interpretation

- The Basics of Arterial Lines

Additional modules are also being developed and will be updated when available.

Online education in critical care for registered nurses

The Commonwealth Government has launched new online education to enable registered nurses to assist in the delivery of care in intensive care and high dependency units.

Some course content is available now, with all content to be available from 9 April 2020.

For more information visit MedCast - SURGE Critical Care

The Australian College of Nursing - 'Online Refresher Program for Registered Nurses'

- The ACN has developed an online course to refresh your knowledge in acute care nursing which is ideal for nurses working in non-acute areas of practice.

- See the ACN website for more details

- The course costs $1100 and will account for 36 CPD hours

More information

Contact: Matthew Lutze Principal Advisor - Nursing Practice and Informatics Nursing & Midwifery Office, NSW Ministry of Health Phone: (02) 9461 7213, Email: [email protected]

Nursing clinical pathway

On this page.

Published: February 2022. Next review: 2027.

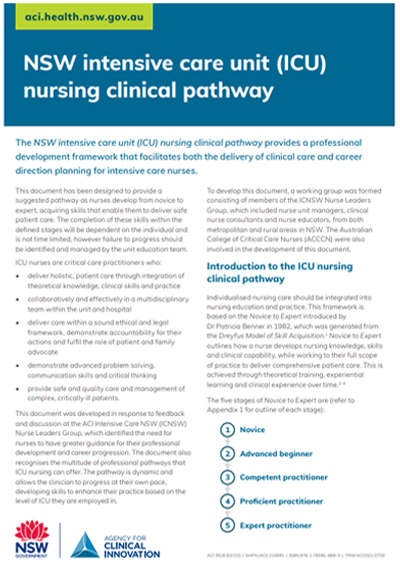

The NSW intensive care unit (ICU) nursing clinical pathway provides a professional development framework to facilitate the delivery of clinical care and career direction planning for intensive care nurses.

The document recognises the various professional pathways that ICU nursing can offer. It allows clinicians to progress at their own pace, developing skills to enhance their practice, based on the level of ICU they are employed in.

Download the NSW ICU nursing clinical pathway (PDF 397.4 KB)

The nursing clinical pathway was developed in response to feedback from the ACI Intensive Care NSW (ICNSW) nurse leaders group. It was identified that ICU nurses need greater guidance for their professional development and career progression.

We would like to acknowledge the representatives from the following groups who led the development of this pathway:

- ICNSW nurse leaders group, including nurse unit managers, clinical nurse consultants and nurse educators, from metropolitan and rural NSW

- The Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN)

For clinicians

Thank you for your feedback.

Your request has been identified as spam.

- ACN FOUNDATION

- SIGNATURE EVENTS

- SCHOLARSHIPS

- POLICY & ADVOCACY

- ACN MERCHANDISE

- MYACN LOGIN

- THE BUZZ LOGIN

- STUDENT LOGIN

- Celebrating 75 years

- ACN governance and structure

- Work at ACN

- Contact ACN

- NurseClick – ACN’s blog

- Media releases

- Publications

- ACN podcast

- Men in Nursing

- NurseStrong

- Recognition of Service

- Free eNewsletter

- Areas of study

- Graduate Certificates

- OSCE – Preparation for Objective Structured Clinical Examination

- Nursing (Re-entry)

- Continuing Professional Development

- Immunisation courses

- Single units of study

- Transition to Practice Program

- Audiometry Nursing in Practice

- Refresher programs

- Principles of Emergency Care

- Medicines Management Course

- Professional Practice Course

- Endorsements

- Student support

- Student policies

- Clinical placements

- Career mentoring

- Indemnity insurance

- Legal advice

- ACN representation

- Affiliate membership

- Undergraduate membership

- Retired membership

- States and Territories

- ACN Fellowship

- Referral discount

- Health Minister’s Award for Nursing Trailblazers

- Emerging Nurse Leader program

- Emerging Policy Leader Program

- Emerging Research Leader Program

- Nurse Unit Manager Leadership Program

- Nurse Director Leadership Program

- Nurse Executive Leadership Program

- The Leader’s Series

- Thought leadership

- Other leadership courses

- National Nursing Forum

- History Faculty Conference

- Next Generation Faculty Summit

- Virtual Open Day

- National Nursing Roadshow

- Policy Summit

- Nursing & Health Expo

- National Nurses Breakfast

- Event and webinar calendar

- Grants and awards

- External nursing scholarships

- Assessor’s login

- ACN Advocacy and Policy

- Position Statements

- Submissions

- White Papers

- Clinical care standards

- Aged Care Solutions Expert Advisory Group

- Nurses and Violence Taskforce

- Parliamentary Friends of Nursing

- Aged Care Transition to Practice Program

- Immunisation

- Join as an Affiliated Organisation

- Our Affiliates

- Our Corporate Partners

- Events sponsorship

- Advertise with us

- Career Hub resources

- Critical Thinking

Q&A: What is critical thinking and when would you use critical thinking in the clinical setting?

(Write 2-3 paragraphs)

In literature ‘critical thinking’ is often used, and perhaps confused, with problem-solving and clinical decision-making skills and clinical reasoning. In practice, problem-solving tends to focus on the identification and resolution of a problem, whilst critical thinking goes beyond this to incorporate asking skilled questions and critiquing solutions.

Critical thinking has been defined in many ways, but is essentially the process of deliberate, systematic and logical thinking, while considering bias or assumptions that may affect your thinking or assessment of a situation. In healthcare, the clinical setting whether acute care sector or aged care critical thinking has generally been defined as reasoned, reflective thinking which can evaluate the given evidence and its significance to the patient’s situation. Critical thinking occasionally involves suspension of one’s immediate judgment to adequately evaluate and appraise a situation, including questioning whether the current practice is evidence-based. Skills such as interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation are required to interpret thinking and the situation. A lack of critical thinking may manifest as a failure to anticipate the consequences of one’s actions.

Critical thinking is that mode of thinking – about any subject, content, or problem — in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them.

The Paul-Elder framework has three components:

- The elements of thought (reasoning)

- The intellectual standards that should be applied to the elements of reasoning

- The intellectual traits associated with a cultivated critical thinker that result from the consistent and disciplined application of the intellectual standards to the elements of thought.

Critical thinking can be defined as, “the art of analysing and evaluating thinking with a view to improving it”. The eight Parts or Elements of Thinking involved in critical thinking:

- All reasoning has a purpose (goals, objectives).

- All reasoning is an attempt to figure something out, to settle some question, to solve some problem .

- All reasoning is based on assumptions (line of reasoning, information taken for granted).

- All reasoning is done from some point of view.

- All reasoning is based on data, information and evidence .

- All reasoning is expressed through, and shaped by, concepts and ideas .

- All reasoning contains inferences or interpretations by which we draw conclusions and give meaning to data.

- All reasoning leads somewhere or has implications and consequence.

Q&A: To become a nurse requires that you learn to think like a nurse. What makes the thinking of a nurse different from a doctor, a dentist or an engineer?

It is how we view the health care consumer or aged care consumer, and the type of problems nurses deal with in clinical practice when we engage in health care patient centred care. To think like a nurse requires that we learn the content of nursing; the ideas, concepts, ethics and theories of nursing and develop our intellectual capacities and skills so that we become disciplined, self-directed, critical thinkers.

As a nurse you are required to think about the entire patient/s and what you have learnt as a nurse including; ideas, theories, and concepts in nursing. It is important that we develop our skills so that we become highly proficient critical thinkers in nursing.

In nursing, critical thinkers need to be:

Nurses need to use language that will clearly communicate a lot of information that is key to good nursing care, for handover and escalation of care for improving patient safety and reducing adverse outcomes, some organisations use the iSoBAR (identify–situation–observations–background–agreed plan–read back) format. Firstly, the “i”, for “identify yourself and the patient”, placed the patient’s identity, rather than the diagnosis, in primary position and provided a method of introduction. (This is particularly important when teams are widely spread geographically.) The prompt, “S” (“situation”) “o” for “observations”, was included to provide an adequate baseline of factual information on which to devise a plan of care. and “B” (“background”), “A” “agreed plan” and “R” “read back” to reinforce the transfer of information and accountability.

In clinical practice experienced nurses engage in multiple clinical reasoning episodes for each patient in their care. An experienced nurse may enter a patient’s room and immediately observe significant data, draw conclusions about the patient and initiate appropriate care. Because of their knowledge, skill and experience the expert nurse may appear to perform these processes in a way that seems automatic or instinctive. However, clinical reasoning is a learnt skill.

Key critical thinking skills – the clinical reasoning cycle / critical thinking process

To support nursing students in the clinical setting, breakdown the critical thinking process into phases;

- Decide/identify

This is a dynamic process and nurses often combine one or more of the phases, move back and forth between them before reaching a decision, reaching outcomes and then evaluating outcomes.

For nursing students to learn to manage complex clinical scenarios effectively, it is essential to understand the process and steps of clinical reasoning. Nursing students need to learn rules that determine how cues shape clinical decisions and the connections between cues and outcomes.

Start with the Patient – what is the issue? Holistic approach – describe or list the facts, people.

Collect information – Handover report, medical and nursing, allied health notes. Results, patient history and medications.

- New information – patient assessment

Process Information – Interpret- data, signs and symptoms, normal and abnormal.

- Analyse – relevant from non-relevant information, narrow down the information

- Evaluate – deductions or form opinions and outcomes

Identify Problems – Analyse the facts and interferences to make a definitive diagnosis of the patients’ problem.

Establish Goals – Describe what you want to happen, desired outcomes and timeframe.

Take action – Select a course of action between alternatives available.

Evaluate Outcomes – The effectiveness of the actions and outcomes. Has the situation changed or improved?

Reflect on process and new learning – What have you learnt and what would you do differently next time.

Scenario: Apply the clinical reasoning cycle, see below, to a scenario that occurred with a patient in your clinical practice setting. This could be the doctor’s orders, the patient’s vital signs or a change in the patient’s condition.

(Write 3-5 paragraphs)

Important skills for critical thinking

Some skills are more important than others when it comes to critical thinking. The skills that are most important are:

- Interpreting – Understanding and explaining the meaning of information, or a particular event.

- Analysing – Investigating a course of action, that is based upon data that is objective and subjective.

- Evaluating – This is how you assess the value of the information that you have. Is the information relevant, reliable and credible?

This skill is also needed to determine if outcomes have been fully reached.

Based upon those three skills, you can use clinical reasoning to determine what the problem is.

These decisions have to be based upon sound reasoning:

- Explaining – Clearly and concisely explaining your conclusions. The nurse needs to be able to give a sound rationale for their answers.

- Self-regulating – You have to monitor your own thought processes. This means that you must reflect on the process that lead to the conclusion. Be on alert for bias and improper assumptions.

Critical thinking pitfalls

Errors that occur in critical thinking in nursing can cause incorrect conclusions. This is particularly dangerous in nursing because an incorrect conclusion can lead to incorrect clinical actions.

Illogical Processes

A common illogical thought process is known as “appeal to tradition”. This is what people are doing when they say it’s always been done like this. Creative, new approaches are not tried because of tradition.

All people have biases. Critical thinkers are able to look at their biases and not let them compromise their thinking processes.

Biases can complicate decision making, communication and ultimately effect patient care.

Closed Minded

Being closed-minded in nursing is dangerous because it ignores other team members points of view. Essential input from other experts, as well as patients and their families are also ignored which ultimately impacts on patient care. This means that fewer clinical options are explored, and fewer innovative ideas are used for critical thinking to guide decision making.

So, no matter if you are an intensive care nurse, community health nurse or a nurse practitioner, you should always keep in mind the importance of critical thinking in the nursing clinical setting.

It is essential for nurses to develop this skill: not only to have knowledge but to be able to apply knowledge in anticipation of patients’ needs using evidence-based care guidelines.

American Management Association (2012). ‘AMA 2012 Critical Skills Survey: Executive Summary’. (2012). American Management Association. http://playbook.amanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/2012-Critical-Skills-Survey-pdf.pdf Accessed 5 May 2020.

Korn, M. (2014). ‘Bosses Seek ‘Critical Thinking,’ but What Is That?,’ The Wall Street Journal . https://www.wsj.com/articles/bosses-seek-critical-thinking-but-what-is-that-1413923730?tesla=y&mg=reno64-wsj&url=http://online.wsj.com/article/SB12483389912594473586204580228373641221834.html#livefyre-comment Accessed 5 May 2020.

School of Nursing and Midwifery Faculty of Health, University of Newcastle. (2009). Clinical reasoning. Instructors resources. https://www.newcastle.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/86536/Clinical-Reasoning-Instructor-Resources.pdf Accessed 11 May 2020

The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing + Examples. Nurse Journal social community for nurses worldwide. 2020. https://nursejournal.org/community/the-value-of-critical-thinking-in-nursing/ Accessed 8 May 2020.

Paul And Elder (2009) Have Defined Critical Thinking As: The Art of Analysing And Evaluating …

https://www.chegg.com/homework-help/questions-and-answers/paul-elder-2009-defined-critical-thinking-art-analyzing-evaluating-thinking-view-improving-q23582096 Accessed 8 May 2020 .

Cody, W.K. (2002). Critical thinking and nursing science: judgment, or vision? Nursing Science Quarterly, 15(3), 184-189.

Facione, P. (2011). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Insight Assessment , ISBN 13: 978-1-891557-07-1.

McGrath, J. (2005). Critical thinking and evidence- based practice. Journal of Professional Nursing, 21(6), 364-371.

Porteous, J., Stewart-Wynne, G., Connolly, M. and Crommelin, P. (2009). iSoBAR — a concept and handover checklist: the National Clinical Handover Initiative. Med J Aust 2009; 190 (11): S152.

Related posts

Planning your career 5 November 2021

Active Listening 4 November 2021

Ethical Leadership 4 November 2021

You are using an outdated browser

Unfortunately Ausmed.com does not support your browser. Please upgrade your browser to continue.

Cultivating Critical Thinking in Healthcare

Published: 06 January 2019

Critical thinking skills have been linked to improved patient outcomes, better quality patient care and improved safety outcomes in healthcare (Jacob et al. 2017).

Given this, it's necessary for educators in healthcare to stimulate and lead further dialogue about how these skills are taught , assessed and integrated into the design and development of staff and nurse education and training programs (Papp et al. 2014).

So, what exactly is critical thinking and how can healthcare educators cultivate it amongst their staff?

What is Critical Thinking?

In general terms, ‘ critical thinking ’ is often used, and perhaps confused, with problem-solving and clinical decision-making skills .

In practice, however, problem-solving tends to focus on the identification and resolution of a problem, whilst critical thinking goes beyond this to incorporate asking skilled questions and critiquing solutions .

Several formal definitions of critical thinking can be found in literature, but in the view of Kahlke and Eva (2018), most of these definitions have limitations. That said, Papp et al. (2014) offer a useful starting point, suggesting that critical thinking is:

‘The ability to apply higher order cognitive skills and the disposition to be deliberate about thinking that leads to action that is logical and appropriate.’

The Foundation for Critical Thinking (2017) expands on this and suggests that:

‘Critical thinking is that mode of thinking, about any subject, content, or problem, in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully analysing, assessing, and reconstructing it.’

They go on to suggest that critical thinking is:

- Self-directed

- Self-disciplined

- Self-monitored

- Self-corrective.

Key Qualities and Characteristics of a Critical Thinker

Given that critical thinking is a process that encompasses conceptualisation , application , analysis , synthesis , evaluation and reflection , what qualities should be expected from a critical thinker?

In answering this question, Fortepiani (2018) suggests that critical thinkers should be able to:

- Formulate clear and precise questions

- Gather, assess and interpret relevant information

- Reach relevant well-reasoned conclusions and solutions

- Think open-mindedly, recognising their own assumptions

- Communicate effectively with others on solutions to complex problems.

All of these qualities are important, however, good communication skills are generally considered to be the bedrock of critical thinking. Why? Because they help to create a dialogue that invites questions, reflections and an open-minded approach, as well as generating a positive learning environment needed to support all forms of communication.

Lippincott Solutions (2018) outlines a broad spectrum of characteristics attributed to strong critical thinkers. They include:

- Inquisitiveness with regard to a wide range of issues

- A concern to become and remain well-informed

- Alertness to opportunities to use critical thinking

- Self-confidence in one’s own abilities to reason

- Open mindedness regarding divergent world views

- Flexibility in considering alternatives and opinions

- Understanding the opinions of other people

- Fair-mindedness in appraising reasoning

- Honesty in facing one’s own biases, prejudices, stereotypes or egocentric tendencies

- A willingness to reconsider and revise views where honest reflection suggests that change is warranted.

Papp et al. (2014) also helpfully suggest that the following five milestones can be used as a guide to help develop competency in critical thinking:

Stage 1: Unreflective Thinker

At this stage, the unreflective thinker can’t examine their own actions and cognitive processes and is unaware of different approaches to thinking.

Stage 2: Beginning Critical Thinker

Here, the learner begins to think critically and starts to recognise cognitive differences in other people. However, external motivation is needed to sustain reflection on the learners’ own thought processes.

Stage 3: Practicing Critical Thinker

By now, the learner is familiar with their own thinking processes and makes a conscious effort to practice critical thinking.

Stage 4: Advanced Critical Thinker

As an advanced critical thinker, the learner is able to identify different cognitive processes and consciously uses critical thinking skills.

Stage 5: Accomplished Critical Thinker

At this stage, the skilled critical thinker can take charge of their thinking and habitually monitors, revises and rethinks approaches for continual improvement of their cognitive strategies.

Facilitating Critical Thinking in Healthcare

A common challenge for many educators and facilitators in healthcare is encouraging students to move away from passive learning towards active learning situations that require critical thinking skills.

Just as there are similarities among the definitions of critical thinking across subject areas and levels, there are also several generally recognised hallmarks of teaching for critical thinking . These include:

- Promoting interaction among students as they learn

- Asking open ended questions that do not assume one right answer

- Allowing sufficient time to reflect on the questions asked or problems posed

- Teaching for transfer - helping learners to see how a newly acquired skill can apply to other situations and experiences.

(Lippincott Solutions 2018)

Snyder and Snyder (2008) also make the point that it’s helpful for educators and facilitators to be aware of any initial resistance that learners may have and try to guide them through the process. They should aim to create a learning environment where learners can feel comfortable thinking through an answer rather than simply having an answer given to them.

Examples include using peer coaching techniques , mentoring or preceptorship to engage students in active learning and critical thinking skills, or integrating project-based learning activities that require students to apply their knowledge in a realistic healthcare environment.

Carvalhoa et al. (2017) also advocate problem-based learning as a widely used and successful way of stimulating critical thinking skills in the learner. This view is echoed by Tsui-Mei (2015), who notes that critical thinking, systematic analysis and curiosity significantly improve after practice-based learning .

Integrating Critical Thinking Skills Into Curriculum Design

Most educators agree that critical thinking can’t easily be developed if the program curriculum is not designed to support it. This means that a deep understanding of the nature and value of critical thinking skills needs to be present from the outset of the curriculum design process , and not just bolted on as an afterthought.

In the view of Fortepiani (2018), critical thinking skills can be summarised by the statement that 'thinking is driven by questions', which means that teaching materials need to be designed in such a way as to encourage students to expand their learning by asking questions that generate further questions and stimulate the thinking process. Ideal questions are those that:

- Embrace complexity

- Challenge assumptions and points of view

- Question the source of information

- Explore variable interpretations and potential implications of information.

To put it another way, asking questions with limiting, thought-stopping answers inhibits the development of critical thinking. This means that educators must ideally be critical thinkers themselves .

Drawing these threads together, The Foundation for Critical Thinking (2017) offers us a simple reminder that even though it’s human nature to be ‘thinking’ most of the time, most thoughts, if not guided and structured, tend to be biased, distorted, partial, uninformed or even prejudiced.

They also note that the quality of work depends precisely on the quality of the practitioners’ thought processes. Given that practitioners are being asked to meet the challenge of ever more complex care, the importance of cultivating critical thinking skills, alongside advanced problem-solving skills , seems to be taking on new importance.

Additional Resources

- The Emotionally Intelligent Nurse | Ausmed Article

- Refining Competency-Based Assessment | Ausmed Article

- Socratic Questioning in Healthcare | Ausmed Article

- Carvalhoa, D P S R P et al. 2017, 'Strategies Used for the Promotion of Critical Thinking in Nursing Undergraduate Education: A Systematic Review', Nurse Education Today , vol. 57, pp. 103-10, viewed 7 December 2018, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0260691717301715

- Fortepiani, L A 2017, 'Critical Thinking or Traditional Teaching For Health Professionals', PECOP Blog , 16 January, viewed 7 December 2018, https://blog.lifescitrc.org/pecop/2017/01/16/critical-thinking-or-traditional-teaching-for-health-professions/

- Jacob, E, Duffield, C & Jacob, D 2017, 'A Protocol For the Development of a Critical Thinking Assessment Tool for Nurses Using a Delphi Technique', Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 73, no. 8, pp. 1982-1988, viewed 7 December 2018, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.13306

- Kahlke, R & Eva, K 2018, 'Constructing Critical Thinking in Health Professional Education', Perspectives on Medical Education , vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 156-165, viewed 7 December 2018, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40037-018-0415-z

- Lippincott Solutions 2018, 'Turning New Nurses Into Critical Thinkers', Lippincott Solutions , viewed 10 December 2018, https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/turning-new-nurses-into-critical-thinkers

- Papp, K K 2014, 'Milestones of Critical Thinking: A Developmental Model for Medicine and Nursing', Academic Medicine , vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 715-720, https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2014/05000/Milestones_of_Critical_Thinking___A_Developmental.14.aspx

- Snyder, L G & Snyder, M J 2008, 'Teaching Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills', The Delta Pi Epsilon Journal , vol. L, no. 2, pp. 90-99, viewed 7 December 2018, https://dme.childrenshospital.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Optional-_Teaching-Critical-Thinking-and-Problem-Solving-Skills.pdf

- The Foundation for Critical Thinking 2017, Defining Critical Thinking , The Foundation for Critical Thinking, viewed 7 December 2018, https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/our-conception-of-critical-thinking/411

- Tsui-Mei, H, Lee-Chun, H & Chen-Ju MSN, K 2015, 'How Mental Health Nurses Improve Their Critical Thinking Through Problem-Based Learning', Journal for Nurses in Professional Development , vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 170-175, viewed 7 December 2018, https://journals.lww.com/jnsdonline/Abstract/2015/05000/How_Mental_Health_Nurses_Improve_Their_Critical.8.aspx

Anne Watkins View profile

Help and feedback, publications.

Ausmed Education is a Trusted Information Partner of Healthdirect Australia. Verify here .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Perspect Med Educ

- v.7(3); 2018 Jun

Constructing critical thinking in health professional education

Renate kahlke.

Centre for Health Education Scholarship, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

Associated Data

Introduction.

Calls for enabling ‘critical thinking’ are ubiquitous in health professional education. However, there is little agreement in the literature or in practice as to what this term means and efforts to generate a universal definition have found limited traction. Moreover, the variability observed might suggest that multiplicity has value that the quest for universal definitions has failed to capture. In this study, we sought to map the multiple conceptions of critical thinking in circulation in health professional education to understand the relationships and tensions between them.

We used an inductive, qualitative approach to explore conceptions of critical thinking with educators from four health professions: medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and social work. Four participants from each profession participated in two individual in-depth semi-structured interviews, the latter of which induced reflection on a visual depiction of results generated from the first set of interviews.

Three main conceptions of critical thinking were identified: biomedical, humanist, and social justice-oriented critical thinking. ‘Biomedical critical thinking’ was the dominant conception. While each conception had distinct features, the particular conceptions of critical thinking espoused by individual participants were not stable within or between interviews.

Multiple conceptions of critical thinking likely offer educators the ability to express diverse beliefs about what ‘good thinking’ means in variable contexts. The findings suggest that any single definition of critical thinking in the health professions will be inherently contentious and, we argue, should be. Such debates, when made visible to educators and trainees, can be highly productive.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40037-018-0415-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

What this paper adds

‘Critical thinking’ is a term commonly used across health professional education, though there is little agreement on what this means in the literature or in practice. We depart from previous work, which most often attempts to create a common definition. Instead, we offer a description of the different conceptions of critical thinking held in health professional education, illustrate their dynamic use, and discuss the tensions and affordances that this diversity brings to the field. We argue that diversity in conceptions of critical thinking can allow educators to express unique and often divergent beliefs about what ‘good thinking’ means in their contexts.

Even though the term critical thinking is ubiquitous in educational settings, there is significant disagreement about what it means to ‘think critically’ [ 1 ]. Predominantly, authors have attempted to develop consensus definitions of critical thinking that would finally put these disagreements to rest (e. g. [ 2 – 5 ]). They define critical thinking variously, but tend to focus on a rational process involving (for example) ‘interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation’ [ 2 ]. Other authors have challenged this perspective by arguing that critical thinking is a more subjective process, emphasizing the role of emotion and relationships [ 6 – 9 ]. In the tradition of critical pedagogy, critical thinking has meant critiquing ideology [ 10 – 12 ]. Last, still others have argued that critical thinking is discipline or subject-specific, meaning that critical thinking is not universal, but does have a relatively stable meaning within different disciplines [ 13 – 18 ]. However, none of these attempts to clarify the ambiguity that surrounds critical thinking have led to agreement, suggesting that each of these perspectives offers, at best, a partial explanation for the persistence of disagreements.

This is problematic in health professional education (HPE) because professional programs are mandated to educate practitioners who have a defined knowledge base and skill set. When curriculum designers, educators, researchers, or policy-makers all agree that we should teach future professionals to ‘think critically’, resting on the assumption that they also agree on what that means, they may find themselves working at cross-purposes. Moreover, the focus on a stable meaning for critical thinking, whether within a discipline or across disciplines, cannot account for the potential value of the multiplicity of definitions that exist. That is, the availability of diverse conceptions of critical thinking likely enables educators to express diverse elements of and beliefs about their work, thereby suggesting a need to explore the conceptions of critical thinking held in HPE, and the contexts that inform those conceptions.

With the historical focus on developing broad definitions of critical thinking and delineating its component skills and dispositions, little has been done either to document the diverse conceptions of this term in circulation amongst active HPE practitioners or, perhaps more importantly, to illuminate the beliefs about what constitutes ‘good thinking’ that lie behind them and the relationships between them. Perhaps clarity in our understanding of critical thinking lies in the flexibility with which it is conceptualized. This study moves away from attempting to create universal definitions of critical thinking in order to explore the tensions that surround different, converging, and competing beliefs about what critical thinking means.

In doing so, we map out conceptions of critical thinking across four health professions along with the beliefs about professional practice that underpin those conceptions. Some of these beliefs may be tied to a profession’s socialization processes and many will be tied to beliefs about ‘good thinking’ that are shared across professions, since health professionals work within shared systems [ 19 ] toward the same ultimate task of providing patient care. It is the variety of ways in which critical thinking is considered by practitioners on the whole that we wanted to understand, not the formal pronouncements of what might be listed as competencies or components of critical thinking within any one profession.

Hence, with this study, we sought to ask:

- How do educators in the health professions understand critical thinking?

- What values or beliefs inform that understanding?

To explore these questions, we adopted a qualitative research approach that focuses on how people interpret and make meaning out of their experiences and actively construct their social worlds [ 20 ].

This study uses an emergent, inductive design in an effort to be responsive to the co-construction of new and unexpected meaning between participants and researchers. While techniques derived from constructivist grounded theory [ 21 ] were employed, methods like extensive theoretical sampling (that are common to that methodology) were not maintained because this study was intended to be broadly exploratory. This ‘borrowing’ of techniques offers the ability to capitalize on the open and broad approach offered by interpretive qualitative methodology [ 20 ] while engaging selectively with the more specific tools and techniques available from constructivist grounded theory [ 22 , 23 ].

The first author has a background in sociocultural and critical theory. Data collection and early analyses were carried out as part of her dissertation in Educational Policy Studies. As a result of her background in critical theory, there was a need for reflexivity focused on limiting predisposition toward participant interpretations of critical thinking that aligned with critical theory. The senior author was trained in cognitive psychology, and contributed to the questioning of results and discussion required to ensure this reflexivity. The first author’s dissertation supervisor also provided support in this way by questioning assumptions made during the initial stages of this work.

Participants were recruited through faculty or departmental listservs for educators. Senior administrators were consulted to ensure that they were aware of and comfortable with this research taking place in their unit. In some cases, administrators identified a few key individuals who were particularly interested in education. These educators were contacted directly by the first author to request participation.

The purposive sample includes four educators from each of four diverse health professional programs ( n = 16 in total): medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and social work. All participants self-identified as being actively involved in teaching in their professional program and all were formally affiliated with either the University of Alberta (Medicine, Nursing, and Pharmacy) or the University of Calgary (Social Work). These four professions were selected to maximize diversity in approaches to critical thinking given that these professions have diverse perspectives and roles with respect to patient care. However, participants all worked in Alberta, Canada, within the same broad postsecondary education and healthcare contexts.

In addition, sampling priority was given to recruiting participants practising in a diverse range of specialties: primary care, geriatrics, paediatrics, mental health, critical care, and various consulting specialties. Specific specialties within each profession are not provided here in an effort to preserve participant anonymity. The goal was not to make conclusions about the perspective of any one group; rather, diversity in profession, practice context, gender, and years in practice was sought to increase the likelihood of illuminating diverse conceptions of critical thinking.

Data generation

Participants were invited to participate in two in-person semi-structured interviews conducted by the first author. All but one participant completed both interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded and interview guides are included in the online Electronic Supplementary Material. The first was about 1 hour in length and discussed how participants think about critical thinking in their teaching, professional practice, and other contexts. Participants were invited to bring a teaching artefact that represented how they teach critical thinking to the interview. Artefacts were used as a visual elicitation strategy to prompt discussion from a new angle [ 24 ]. Questions focused on what the participant thought about teaching critical thinking using the artefact and how they identified critical thinking (or lack thereof) in their students. Artefacts were not analyzed independently of the discussion they produced [ 25 ].

Interview 1 data were analyzed to produce a visual depiction of the aggregate terms, ideas, and relationships described by participants. The visual depiction took the form of a ‘mind map’ (see Appendix C of the Electronic Supplementary Material) that was generated using MindMup free online software [ 26 ]. In developing the mind map, we sought descriptions of participants’ views that remained as close to the data as possible, limiting interpretations and inferences. The ‘clusters’ that appear in the mind map (e. g., the cluster around ‘characteristics of the critical thinker’) represent relationships or categories commonly described when participants discussed those terms. Terms were not weighted or emphasized based on frequency of use (through font size or bolding) in an effort to allow individual participants to emphasize or deemphasize terms as they thought appropriate during the second interview.

Where there was no clear category or relationship, terms were left at the first level of the mind map, connected directly to ‘critical thinking’ at the centre. Including more connections and inferences would likely have improved the readability of the map for participants; however, we chose to include connections and exact language used by participants (even in cases where terms seemed similar) as often as possible, in an effort to limit researcher interpretation. That said, any attempt to aggregate data or to represent relationships is an act of interpretation and some inferences were made in the process, such as the distinction between descriptions about ‘characteristics’ of the critical thinker (the top left hand corner of the map) and ‘processes’ such as ‘reasoning’ or ‘examining assumptions’ (on the right side of the map). The second interview lasted approximately 45 minutes during which a visual elicitation approach invited participants to respond to the mind map.

Visual elicitation involves employing visual stimuli to generate verbal interview data. Participant-generated mind maps are often used in qualitative data collection [ 27 ], but the literature on using researcher-generated diagrams for visual elicitation is relatively thin [ 25 , 28 ]. In this study, using a researcher-generated mind map for visual elicitation offered several advantages. First, as with other forms of visual elicitation, diagrams of this kind can help participants develop candid responses and avoid rehearsed narratives [ 24 , 29 ]. For example, we used mind maps as one mechanism to reduce the tendency for participants who were familiar with the literature on critical thinking to get stuck on narrating seemingly rehearsed definitions of critical thinking. Second, we chose to use a mind map because it provided a social setting through which participants could react to language generated by others. Doing so does not allow the same degree of social negotiation inherent in focus groups, but it avoids the difficulty involved in attempts to disentangle individual from group views [ 30 ]. Third, the visual elicitation method was chosen because it offered a form of member check [ 31 ] that allowed researchers to understand the evolving nature of participants’ conceptions of critical thinking, rather than assuming that participants offer a single true conception during each and every discussion [ 32 ]. In other words, the mind map was used to prompt participants to elaborate their conception of critical thinking and locate it relative to other participants.

In interview 2, participants were asked to begin by discussing areas or terms on the mind map that resonated most with their own conception of critical thinking; they were then asked to discuss terms or concepts on the map that resonated less or with which they disagreed. They were also asked to comment on how relationships between ideas were represented through the map so that researchers could get a sense of the extent to which the relationships between the concepts depicted reflected the participants’ understanding of those relationships [ 28 ]. Participants were encouraged to disagree with portions of the map and most did actively disagree with some of the terms and relationships depicted, suggesting that the map did not come to dictate more than elicit individual interpretations [ 28 ]. Although participants were encouraged to ‘mark up’ the mind map, and the ‘marked up’ mind maps were treated as data, the primary data sources for this study were the audio-recorded interviews [ 25 ].

Participants were aware that the mind map represented aggregate data from the four health professions in the study, but were not initially told whether any of the responses came predominantly from any one profession; they did not generally seem to be attempting to associate terms with other professions. Nonetheless, interview 2 data are a mix of participants’ reactions to the ideas of others and their elaborations of their own understandings. Naturally, these data build on data generated in interview 1, and represent reactions to both the researcher interpretation of the data and to the conceptions of critical thinking offered by others. Interview 1 data tended to offer an initial, open impression of how participants think about critical thinking in their contexts. Because of these different approaches to data generation, quotes from interview 1 and 2 are labelled as ‘INT1’ or ‘INT2’, respectively.

Data analysis

Data were coded through an iterative cycle of initial and focused coding [ 33 ] with NVivo software. Initial line-by-line coding was used to develop codes that were close to the data, involving minimal abstraction. Initial codes were reviewed by the first author and dissertation supervisor to abstract categories (conceptions of critical thinking), sub-categories (features of those conceptions), and themes related to the relationships between those categories. Focused coding involved taking these categories and testing them against the data using constant comparison techniques derived from constructivist grounded theory [ 21 ]. Category development continued during the framing of this paper, and authors engaged in ongoing conversations to modify categories to better fit the data. In this process, we returned to the data to look for exceptions that did not fit any category, as well as contradictions and overlap between categories.

Interpretive sufficiency [ 34 ], in this study, occurred when no new features illustrating participants’ conceptions of critical thinking were identified. Memos were kept to track the development or elimination of initial insights or impressions. Institutional ethics approval was obtained from the University of Alberta.

Participant identities have been masked to preserve anonymity. The abbreviation ‘MD’ refers to educators in medical education, ‘NURS’ to nursing, ‘PHARM’ to pharmacy, and ‘SW’ to social work. Participants within each group were then assigned a number. For example, the code NURS3 is a unique identifier for a single participant.

Three main conceptions of critical thinking were identified, each of which will be elaborated in greater detail below: biomedical critical thinking, humanist critical thinking, and social justice-oriented critical thinking. It is important to note that these categories focus on the process and purpose of critical thinking, as defined by participants. Participant comments also spoke to the ‘characteristics’ or ‘dispositions’ of critical thinkers, such as ‘open-mindedness’ or ‘creativity’. The focus of this study, however, was on uncovering what critical thinking looks like as opposed to what a ‘critical thinker’ looks like.

The results below interweave responses from different professional groups in order to emphasize the way in which each of the three core conceptions that we have identified crosses professional boundaries. We then provide a brief discussion of the relationships between these three conceptions, emphasizing the limited extent to which these conceptions were profession-specific, and the tensions that we observed between these conceptions. In general, we also interweave results from both interviews because the discussion in interview 2 tended to reinforce the themes arising from interview 1, especially with respect to indications that different conceptions were used fluidly by individuals over time and dependent on the context being discussed. The interview from which data arose is marked after each quote and we have mentioned explicitly whenever a comment was made in specific response to the mind map presented during interview 2.

In this way, our data extend the literature on critical thinking by offering an appreciation of how each of these conceptions provide educators a different way of thinking, talking, and teaching about their work in HPE. We found that even individual participants’ conceptions of critical thinking shifted from time to time. That is, they often articulated more than one understanding of critical thinking over the course of an interview or between interviews 1 and 2. Some of these conceptions were shared by multiple participants but individual constellations of beliefs about what critical thinking means were unique and somewhat idiosyncratic. Thus, while participants’ conceptions of critical thinking were both idiosyncratic and common, they were also flexible and contextual; the meaning of critical thinking was continuously reconstructed and contested. In this way, critical thinking offered a window through which to explore how beliefs about what constitutes ‘good thinking’ in a profession are challenged in educational settings.

Biomedical critical thinking

Participants articulating a biomedical approach saw critical thinking and clinical reasoning as nearly synonymous. They emphasized a process that was rational, logical, and systematic. One participant articulated that critical thinking is ‘ to be able to reason logically’ (NURS4 INT1). Another related:

You have to kind of pull together data that’s relevant to the subject you’re dealing with. You have to interpret it, you have to analyse it, and you have to come up with some type of conclusions at the end as to how you deal with it. (PHARM3 INT1)

Participants discussing this approach agreed that critical thinking involved a systematic process of gathering and analyzing data: ‘I think [critical thinking and clinical reasoning] are the same. I think clinical reasoning is basically taking the data you have on a patient and interpreting it, and offering a treatment plan’ (MD1 INT1).

In keeping with an emphasis on the rational and logical, participants espousing this view often reacted negatively when they saw references to emotion on the mind map in interview 2: ‘as soon as you bring your emotions into the room, you’re no longer applying what I think is critical thinking’ (MD4 INT2). Participants also noted that decision-making was an important component of critical thinking: ‘ you have to make a decision. I think it’s a really important part of it’ (MD2 INT2).

For participants from pharmacy, in particular, critical thinking often meant departing from ‘rules’ that guide clinical practice in order to engage in reasoning and make situationally nuanced decisions. One pharmacist, describing a student not engaging in critical thinking, related that the student asked:

‘Have you ever seen Victoza given at 2.4 milligrams daily?’ … It’s very, you know, it’s very much yes or no. But at a deeper level, it’s actually missing things. … [There are] all these other factors that change the decision, right? … On paper there might be a regular set of values for the dose, … [but] without the rest of the background, that’s a very secondary thing. (PHARM4 INT1)

This perspective was identified as the dominant conception of critical thinking because the terms and concepts falling under this broad approach were most frequently discussed by participants; moreover, when participants discussed other conceptions of critical thinking, they were often explicitly drawing contrast to the biomedical view. While the biomedical perspective was dominant in all four groups (although primarily as a contrasting case for social workers), participants tended to occupy more than one perspective over the course of an interview. They might talk primarily about biomedical critical thinking, but also explicitly modify that perspective by drawing on the other two approaches identified: humanist critical and social justice-oriented critical thinking.

Humanist critical thinking

Participants, when adopting this view, described critical thinking as directed toward social good and oriented around positive human relationships. Humanist conceptions of critical thinking were often positioned as an alternative to the dominant biomedical perspective: ‘having to think of somebody else, at their most vulnerable, makes you know that knowledge alone, science alone, won’t get that patient to the place you want the patient to be. It won’t provide the best care’ (NURS1 INT1). In being so positioned, the humanist conception of critical thinking explicitly departed from the biomedical, which emphasized ‘setting aside’ emotion and de-emphasized the role of relationships in healthcare. In the humanist perspective, participants often discussed the purpose of critical thinking as:

Thinking about something for the betterment of yourself and the betterment of others. We’re social beings as human beings. … I think [critical thinking] has a higher purpose. … But I think that [if] critical thinking … [is] a human trait that we have or hope to have, then it has to have those components of what we are as humans. (NURS1 INT1)

Another participant emphasized that: ‘a great part of critical thinking is that human element and the consideration of ultimately what’s a good thing, a common good’ (NURS2 INT1).

In addressing the relational aspects of humanist critical thinking, participants argued that the focus on ‘hard’ sources of data, such as lab tests or imaging, in biomedical critical thinking was limiting. They were concerned that ‘hard data’ tend to be perceived as more objective and thus more important in biomedical critical thinking, compared with subjective patient narratives. They argued that the patient’s story is essential to critical thinking:

I think it doesn’t matter what kind of expert you are, you have to be able to think about patients in the context that they’re in and consider what the patient has to say, and really hear them. So I think that’s an important—that was a total lack of critical thinking in a totally, ‘I’m just going to get through this next patient to the next one’ . (MD1 INT1)

Taken together, these perspectives suggest that biomedical approaches to critical thinking fail to address the complex relational and psychosocial aspects of professional practice.

Social justice-oriented critical thinking

In social justice-oriented approaches to critical thinking participants articulated a process of examining the assumptions and biases embedded in their world. They often explicitly rejected biomedical conceptions of critical thinking as ‘ reductionistic ’ (SW3 INT1) because, in their view, these approaches fail to address the thinker’s own biases. Educators taking a social justice approach felt that: ‘critical thinking … is around things like … recognizing your own bias and recognizing the bias in the world’ (SW1 INT1). In this perspective, participants saw critical thinking as a process of analyzing and addressing the ways in which individual and societal assumptions limit possible actions and access to resources for individuals and social groups.

Unlike biomedical critical thinking and similar to the humanist view, participants articulating this conception tended to make the values and goals of critical thinking, as they conceived of it, explicit. They often contrasted their articulation of values in critical thinking with the ‘assumed’ and unarticulated values present in the biomedical perspective:

If you are not orientated in a social justice position, [critical thinking is] more about the mechanics, which is valuable as well, but … if we don’t understand the values associated with what we think, it seems to not be meaningless but there’s a piece missing or it’s assumed. The values are assumed. (SW3 INT1)

When taking this perspective, participants argued that it is necessary to understand social systems in order to think critically about individual patient cases. One educator questioned:

Why are there a disproportionate number of aboriginal inpatients than any other group? … When you start critically thinking about seeing the whole patient … there are issues related with all of society and that’s why people have more diabetes. (PHARM1 INT1)

Other participants had measured responses to this approach. One participant added to their primarily biomedical approach in order to accommodate perspectives encountered in the mind map, relating that behind their diagnostic work all physicians:

Certainly see a wide spectrum of social and economic status and cultures and things and recognizing that our system is kind of biased against certain groups as it is and knowing that but really not having a good sense of knowing even where to start deconstructing it. (MD2 INT2)

Relationships between conceptions of critical thinking

Results of this study suggest that critical thinking means a variety of things in different contexts and to different people. It might be tempting to see the three approaches outlined above as playing out along professional boundaries. Certainly, the social justice-oriented conception was more common among social work educators; the humanist approach was most common among participants from nursing; perspectives held by physician educators frequently aligned with dominant biomedical conceptions. In pharmacy, educators seemed to straddle all three perspectives, though they commonly emphasized a biomedical approach. Several participants suggested that their faculty or profession has a common understanding of critical thinking: ‘ critical thinking, for me and maybe for our faculty, is around things like … ’ (SW1 INT1).

However, while the disciplinary tendencies discussed above do appear in the data, these tendencies were not stable; participants often held more than one view on what critical thinking meant simultaneously, or shifted between perspectives. Participants also articulated approaches that were not common in their profession at certain moments, positioning themselves as ‘an outlier’, or positioning their specialty as having a different perspective than the profession as a whole, such that critical thinking might mean ‘thinking like a nurse’, or ‘thinking in geriatrics’. Further, participants’ perspectives shifted depending on the context in which they imagined critical thinking occurring.

This type of positioning and re-positioning occurred in both interviews, although they were particularly pronounced in interview 2, where participants were explicitly asked to react to different viewpoints by responding to the mind map. Examples of shifting perspectives in interview 1 occurred especially when participants from medicine shifted between biomedical and humanist conceptions. These shifts suggested a persistent tension and negotiation between characterizations of critical thinking as a rational process of data collection and analysis, and a more humanist approach that accounts for emotion and the relationship between professional and patient or family. Where participants sought to extend their notion of data beyond ‘hard data’ there is a sense of blending humanism with biomedical approaches to critical thinking. In the quote below, the participant brings together a call for a humanist relationship building with a need to gather and analyze all of the data, including important data about the patient’s experience:

I have colleagues who’ll say [to their patients]: ‘just say yes or no.’ … And it’s not very good and they’re missing stuff. So, critical thinking is—I guess it’s sort of dynamic in that you have to have time and you also have to have an interaction. (MD1 INT1)

While the participants described above negotiated between biomedical and humanist perspectives, participants primarily espousing a social justice-oriented conception of critical thinking responded to the ‘assumed’ values of the biomedical model. In talking about a problem solving-oriented biomedical approach, one participant argued that ‘ it’s important as well to have that, those foundational elements of how we think about what we think, but if we don’t understand the values associated … there’s a piece missing’ (SW3 INT1). Another stated that ‘critical thinking seems to be a neutral kind of process or—no, that can’t be true, can it?’ (SW1 INT2) with the mid-sentence shift indicating that two ways of conceptualizing critical thinking had come into conflict. This participant primarily discussed a social justice-oriented conception of critical thinking, which is not neutral, but at this moment also articulated a neutral, clinical reasoning-oriented or biomedical conception.

These relatively organic moments of negotiation certainly demonstrate a sense of conflicting values, of toggling between one perspective and another. However, they also suggest that there are ways in which these contradictions can be productively sustained. In negotiating between humanist and biomedical perspectives, educators effectively modify the dominant perspective.

In interview 2, when discussing the mind map, participants often encountered views that differed from their own. They responded either by making sense of and accommodating the new perspective, or by rejecting it. As an example of the former approach, one physician reacted to the ‘social justice-oriented’ corner of the mind map (specifically ‘examining assumptions’) by explaining how there are:

Assumptions in the background that come up for me all the time in terms of the different ways people live and want to live and how we run into it all the time … it’s always in the background and actually influencing you and until someone challenges the way you approached something, you don’t know what your assumptions are. (MD1 INT2)

As an example of a participant disagreeing with a perspective encountered in the mind map, one participant rejected social justice as an important component of critical thinking in medicine. They related that critical thinking has ‘got everything to do with reasoning, which makes sense. … Social justice has nothing to do with critical thinking’ (MD4 INT2). Interestingly, this participant also spoke at length about the link between social justice and critical thinking in the first interview, suggesting that a conception might seem ‘wrong’ when an individual is thinking and talking about it in one context, and entirely ‘right’ in another context.

Such results demonstrate that individual conceptions of critical thinking are multiple and flexible, not predetermined or stable. Educators bring certain values or perspectives into the foreground as they relate to the context under discussion, while others recede into the background. Though many participants seemed to have a primary perspective, multiple perspectives on critical thinking can co-exist and are actively negotiated by the individual.

In overview, the three broad conceptions of critical thinking offered here (biomedical, humanist, and social justice-oriented) echo approaches to critical thinking found in the critical thinking literature [ 11 , 35 – 37 ]. However, this study extends the literature in two key ways. First, our data point to ways in which different conceptions of critical thinking conflict and coalesce, within the field, within each profession, and even within individuals. Second, this tension offers an early empirical account of critical thinking in the health professions that suggests there may be benefits to maintaining flexibility in how one conceives of the concept.

The diverse conceptions of critical thinking identified all appear to have some value in HPE. It might be tempting to view each conception as a unique but stable perspective, reflecting thinking skills that are used within a particular context or value orientation. However, the multiplicity and flexibility of participants’ conceptions in this study offers some explanation as to why previous attempts to develop either generic (e. g. [ 2 , 3 , 5 ]) or discipline-specific [ 13 , 15 – 17 ] definitions and delineations of critical thinking have failed to stick.

Conceptions of critical thinking are not stable within a context or for a single educator. Educators’ conceptions of critical thinking shift within and between contexts as they navigate overlapping sets of values and beliefs. When educators take up different conceptions of critical thinking, the shifts they make are not just pragmatic; they actively negotiate the values and practices of the different communities in which they participate. Although we certainly saw hints of differences between professions, the strength of this study is that it captured the ways in which conceptions of critical thinking are not stably tied to any given profession. Critical thinking is connected to a broader idea of what ‘good thinking’—and, by extension, the ‘good professional’—looks like for each educator [ 38 ] within a given context or community.

These observations lead one to speculate about what purpose fluidity in conceptions of critical thinking might serve. Educators often have different values and goals for their profession, and, thus, it is not surprising that the meaning of critical thinking would be contested both within and across professions. Through their conceptions of critical thinking, participants contest ideas about what thinking is for in their profession—whether it should be focused on individual patient ‘problems’ or broader social issues, and the extent to which humanism is an important component of healthcare.

It is understandable that so much of the literature on critical thinking has sought to clarify a single ‘right’ definition; there is an argument for making a collective decision about what ‘good thinking’ means. Such a decision might offer clarity to interprofessional teaching and practice, or provide a foundation on which educational policy can be based. However, the critical thinking literature has long sought such a universal agreement and disagreements persist. Results of this study suggest a new approach, one that can account for multiple conceptions of critical thinking within and across health professions and practice contexts. The visual elicitation approach employed, asking participants to respond to the mind map, offered a unique perspective on the data that illuminated contradictions between conceptions held by individual participants, between participants, and between the conceptions themselves.

Such an approach offers a vehicle for thinking and talking about what kind of thinking is valued, both within and between professions. When conceptions of critical thinking are understood as flexible instead of stable, these acts of modification and contestation can be viewed as potential moments for critical self-reflection for individuals and for professional groups on the whole. Moreover, through their discussions of critical thinking, educators actively intervened to consider and assert what they value in their work.

These different conceptions might be complementary as often as they are incompatible. In fact, we would argue that ‘good thinking’ is inherently contentious (and should be) because it is such struggles over what ‘the good’ means in HPE that allow for challenges to the status quo. Advances at the heart of HPE and practice have been hard-won through deliberate reflection, discussion, action, and (often) conflict. For example, the ongoing movement toward relationship-oriented care has arguably occurred as a result of unexpected pushback regarding the limits of considering good healthcare as being entirely patient-centred. Thus, there is a need to bring unarticulated assumptions about important topics into the light so that the goals and values of educators and policy-makers can be openly discussed, even though they are unlikely to ever be fully resolved.

Strengths and limitations

This study offered a broad sample of educators from four different professions, who practised in a range of disciplinary contexts. Given that the sampling approach taken sought breadth rather than depth, the results explore a range of conceptions of critical thinking across HPE, rather than allowing strong claims about any one profession or context. The sample also focussed on conceptions of critical thinking within health professions education at specific institutions in Edmonton, Alberta. A multi-institutional study might build on these results to elaborate the extent to which each health profession has a core shared conception of critical thinking that translates across institutional settings. We expect that there may be significant differences between settings, given that what is meant by critical thinking seems to be highly contextual, even from moment to moment. Mapping aspects of context that impact how individuals and groups think about critical thinking would tell us much more about the values on which these conceptions are based.

Subsequent studies might also explore the extent to which conceptions of critical thinking among those identifying as ‘educators’ are comparable to those identifying as primarily ‘clinicians’. Although the boundary is definitely blurry, these groups engage in different kinds of work and participate in different communities, which we suspect may result in differences in how they conceive of critical thinking.

Conclusions

Rather than attempting to ‘solve’ the debate about what critical thinking should mean, this study maps the various conceptions of this term articulated by health professional educators. Educators took up biomedical, humanist, and social justice-oriented conceptions of critical thinking, and their conceptions often shifted from moment to moment or from context to context. The ‘mapping’ approach adopted to study this issue allowed for an appreciation of the ways in which educators actively modify and contest educational and professional values, even within their own thinking. Because critical thinking appears to be both value and context driven, arriving at a single right definition or taxonomy of critical thinking is unlikely to resolve deep tensions around what ‘good thinking’ in HPE means. Moreover, such an approach is unlikely to be productive. Such tensions produce challenges for shared understanding at the same time that they produce a productive space for discussion about core issues in HPE.

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

We thank Dr. Paul Newton for his contributions to the analysis of these data, in his role as supervisor of the dissertation work on which this manuscript is based. Thanks also to Dr. Dan Pratt for his help and support in developing this manuscript.

Support for this work was provided by the Government of Alberta (Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship), by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Doctoral Fellowship), and by the University of British Columbia (Postdoctoral Fellowship).

Biographies

PhD, is Postdoctoral Fellow in the Centre for Health Education Scholarship, University of British Columbia. This manuscript reports on doctoral research at the Department of Educational Policy Studies, University of Alberta.

PhD, is Associate Director and Senior Scientist in the Centre for Health Education Scholarship, and Professor and Director of Educational Research and Scholarship in the Department of Medicine, at the University of British Columbia.

Conflict of interest

R. Kahlke and K. Eva declare that they have no competing interests.

News & Events

Education & training, placements, scholarships & grants, research & innovation, resources & links, nsw health rto.

- Continuous Professional Development

- Redirect from contact-us-form to contact-us

Find out about our team, how we partner with and support NSW Health, working for HETI and more.

Our Organisation

- Vision Purpose Mission

- Strategic Plan

- Core Values

- Organisational Structure

Higher Education

- Public Access

- Public Interest Disclosures

Accreditation and Registrations

- Registered Training Organisation

District HETI Course Development

Work for heti.

Stay up to date with HETI news, events, new projects and resources under development.

Consultations

From short eLearning modules and workshops, to immersive programs and Masters-level courses – HETI supports the full range of clinical and non-clinical roles across NSW Health and beyond.

Courses and programs

- Search our database of education and training opportunities

Our Focus Areas

- Allied Health

- Genetics and Genomics

- Leadership and Management

- Mental Health

- Nursing and Midwifery

- Rural and Remote

- Virtual Care

- Applied Mental Health Studies

- Psychiatric Medicine

- Professional Development / Microcredentials

My Health Learning

- Professional Development

- Mandatory Training

- Continuing Professional Development

- My Professional Development

Case Studies and Profiles

We manage the recruitment of medical interns, cadetships and student clinical placements across NSW Health. Scholarships and grants are also offered to support equal access to education.

Medical Internships

Student placements, scholarships and grants, mental health awards.

HETI draws on the latest technology, innovative learning methods and evidence-based research to design contemporary, responsive health education and training.

Innovation at HETI

- Our Approach

- Research Community

- Publishing Research

- Evaluation and Research Webcast Series

Search our publications, guidelines and other useful documents and links.

Resource Library

External links.

Intensive Care Transition to Specialty Practice

The Health Education and Training Institute and the Agency for Clinical Innovation’s (ACI) Intensive Care NSW Network have redesigned the Intensive Care Unit Transition to Specialty Practice (ICU TTSP) program to create a contemporary education pathway that builds capacity in ICU nursing in NSW.

The program offers a standardised yet flexible education pathway to support nurses transitioning into the dynamic and potentially high-pressure critical care environment.

Contemporary education pathway for early-career ICU nurses

The new ICU TTSP is a statewide, person-centred blended learning program that merges evidence-based practice, authentic scenarios, clinician perspectives and patient’s lived experiences with robust educational design.

Program Accreditation

NSW Health nurses who have completed the ICU TTSP assessment stream can receive credit recognition for postgraduate studies with our University partners.

Launch event

The ICU TTSP Program was launched by HETI, Agency for Clinical Innovation and the Nursing and Midwifery Office on 1 February 2023. Watch the key addresses and presentations from the event.

For more information about the ICU TTSP Program, please contact Amanda Hooton , Associate Director, Education Strategy, Research & Evaluation.

ANA Nursing Resources Hub

Search Resources Hub

Critical Thinking in Nursing: Tips to Develop the Skill

4 min read • February, 09 2024

Critical thinking in nursing helps caregivers make decisions that lead to optimal patient care. In school, educators and clinical instructors introduced you to critical-thinking examples in nursing. These educators encouraged using learning tools for assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Nurturing these invaluable skills continues once you begin practicing. Critical thinking is essential to providing quality patient care and should continue to grow throughout your nursing career until it becomes second nature.

What Is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing involves identifying a problem, determining the best solution, and implementing an effective method to resolve the issue using clinical decision-making skills.

Reflection comes next. Carefully consider whether your actions led to the right solution or if there may have been a better course of action.

Remember, there's no one-size-fits-all treatment method — you must determine what's best for each patient.

How Is Critical Thinking Important for Nurses?

As a patient's primary contact, a nurse is typically the first to notice changes in their status. One example of critical thinking in nursing is interpreting these changes with an open mind. Make impartial decisions based on evidence rather than opinions. By applying critical-thinking skills to anticipate and understand your patients' needs, you can positively impact their quality of care and outcomes.

Elements of Critical Thinking in Nursing

To assess situations and make informed decisions, nurses must integrate these specific elements into their practice:

- Clinical judgment. Prioritize a patient's care needs and make adjustments as changes occur. Gather the necessary information and determine what nursing intervention is needed. Keep in mind that there may be multiple options. Use your critical-thinking skills to interpret and understand the importance of test results and the patient’s clinical presentation, including their vital signs. Then prioritize interventions and anticipate potential complications.

- Patient safety. Recognize deviations from the norm and take action to prevent harm to the patient. Suppose you don't think a change in a patient's medication is appropriate for their treatment. Before giving the medication, question the physician's rationale for the modification to avoid a potential error.