InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development

This brief is part of a series that summarizes essential scientific findings from Center publications.

Content in This Guide

Step 1: why is early childhood important.

- : Brain Hero

- : The Science of ECD (Video)

- You Are Here: The Science of ECD (Text)

Step 2: How Does Early Child Development Happen?

- : 3 Core Concepts in Early Development

- : 8 Things to Remember about Child Development

- : InBrief: The Science of Resilience

Step 3: What Can We Do to Support Child Development?

- : From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts

- : 3 Principles to Improve Outcomes

The science of early brain development can inform investments in early childhood. These basic concepts, established over decades of neuroscience and behavioral research, help illustrate why child development—particularly from birth to five years—is a foundation for a prosperous and sustainable society.

Brains are built over time, from the bottom up.

The basic architecture of the brain is constructed through an ongoing process that begins before birth and continues into adulthood. Early experiences affect the quality of that architecture by establishing either a sturdy or a fragile foundation for all of the learning, health and behavior that follow. In the first few years of life, more than 1 million new neural connections are formed every second . After this period of rapid proliferation, connections are reduced through a process called pruning, so that brain circuits become more efficient. Sensory pathways like those for basic vision and hearing are the first to develop, followed by early language skills and higher cognitive functions. Connections proliferate and prune in a prescribed order, with later, more complex brain circuits built upon earlier, simpler circuits.

The interactive influences of genes and experience shape the developing brain.

Scientists now know a major ingredient in this developmental process is the “ serve and return ” relationship between children and their parents and other caregivers in the family or community. Young children naturally reach out for interaction through babbling, facial expressions, and gestures, and adults respond with the same kind of vocalizing and gesturing back at them. In the absence of such responses—or if the responses are unreliable or inappropriate—the brain’s architecture does not form as expected, which can lead to disparities in learning and behavior.

The brain’s capacity for change decreases with age.

The brain is most flexible, or “plastic,” early in life to accommodate a wide range of environments and interactions, but as the maturing brain becomes more specialized to assume more complex functions, it is less capable of reorganizing and adapting to new or unexpected challenges. For example, by the first year, the parts of the brain that differentiate sound are becoming specialized to the language the baby has been exposed to; at the same time, the brain is already starting to lose the ability to recognize different sounds found in other languages. Although the “windows” for language learning and other skills remain open, these brain circuits become increasingly difficult to alter over time. Early plasticity means it’s easier and more effective to influence a baby’s developing brain architecture than to rewire parts of its circuitry in the adult years.

Cognitive, emotional, and social capacities are inextricably intertwined throughout the life course.

The brain is a highly interrelated organ, and its multiple functions operate in a richly coordinated fashion. Emotional well-being and social competence provide a strong foundation for emerging cognitive abilities, and together they are the bricks and mortar that comprise the foundation of human development. The emotional and physical health, social skills, and cognitive-linguistic capacities that emerge in the early years are all important prerequisites for success in school and later in the workplace and community.

Toxic stress damages developing brain architecture, which can lead to lifelong problems in learning, behavior, and physical and mental health.

Scientists now know that chronic, unrelenting stress in early childhood, caused by extreme poverty, repeated abuse, or severe maternal depression, for example, can be toxic to the developing brain. While positive stress (moderate, short-lived physiological responses to uncomfortable experiences) is an important and necessary aspect of healthy development, toxic stress is the strong, unrelieved activation of the body’s stress management system. In the absence of the buffering protection of adult support, toxic stress becomes built into the body by processes that shape the architecture of the developing brain.

Policy Implications

- The basic principles of neuroscience indicate that early preventive intervention will be more efficient and produce more favorable outcomes than remediation later in life.

- A balanced approach to emotional, social, cognitive, and language development will best prepare all children for success in school and later in the workplace and community.

- Supportive relationships and positive learning experiences begin at home but can also be provided through a range of services with proven effectiveness factors. Babies’ brains require stable, caring, interactive relationships with adults — any way or any place they can be provided will benefit healthy brain development.

- Science clearly demonstrates that, in situations where toxic stress is likely, intervening as early as possible is critical to achieving the best outcomes. For children experiencing toxic stress, specialized early interventions are needed to target the cause of the stress and protect the child from its consequences.

Suggested citation: Center on the Developing Child (2007). The Science of Early Childhood Development (InBrief). Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu .

Related Topics: toxic stress , brain architecture , serve and return

Explore related resources.

- Reports & Working Papers

- Tools & Guides

- Presentations

- Infographics

Videos : Serve & Return Interaction Shapes Brain Circuitry

Reports & Working Papers : From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts

Briefs : InBrief: The Science of Neglect

Videos : InBrief: The Science of Neglect

Reports & Working Papers : The Science of Neglect: The Persistent Absence of Responsive Care Disrupts the Developing Brain

Reports & Working Papers : Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships

Tools & Guides , Briefs : 5 Steps for Brain-Building Serve and Return

Briefs : 8 Things to Remember about Child Development

Partner Resources : Building Babies’ Brains Through Play: Mini Parenting Master Class

Podcasts : About The Brain Architects Podcast

Videos : FIND: Using Science to Coach Caregivers

Videos : How-to: 5 Steps for Brain-Building Serve and Return

Briefs : How to Support Children (and Yourself) During the COVID-19 Outbreak

Videos : InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development

Partner Resources , Tools & Guides : MOOC: The Best Start in Life: Early Childhood Development for Sustainable Development

Presentations : Parenting for Brain Development and Prosperity

Videos : Play in Early Childhood: The Role of Play in Any Setting

Videos : Child Development Core Story

Videos : Science X Design: Three Principles to Improve Outcomes for Children

Podcasts : The Brain Architects Podcast: COVID-19 Special Edition: Self-Care Isn’t Selfish

Podcasts : The Brain Architects Podcast: Serve and Return: Supporting the Foundation

Videos : Three Core Concepts in Early Development

Reports & Working Papers : Three Principles to Improve Outcomes for Children and Families

Partner Resources , Tools & Guides : Training Module: “Talk With Me Baby”

Infographics : What Is COVID-19? And How Does It Relate to Child Development?

Partner Resources , Tools & Guides : Vroom

Early Childhood Development: the Promise, the Problem, and the Path Forward

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, tamar manuelyan atinc and tamar manuelyan atinc nonresident senior fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education emily gustafsson-wright emily gustafsson-wright senior fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education.

November 25, 2013

- 17 min read

Access more content from the Center for Universal Education here , including work on early childhood education .

Early Childhood: The Scale of the Problem

More than 200 million children under the age of five in the developing world are at risk of not reaching their full development potential because they suffer from the negative consequences of poverty, nutritional deficiencies and inadequate learning opportunities (Lancet 2007). In addition, 165 million children (one in four) are stunted, with 90 percent of those children living in Africa and Asia (UNICEF et al, 2012). And while some progress has been made globally, child malnutrition remains a serious public health problem with enormous human and economic costs. Child death is a tragedy. At 6 million deaths a year, far too many children perish before reaching the age of five, but the near certainty that 200 million children today will fall far below their development potential is no less a tragedy.

There is now an expanding body of literature on the determining influence of early development on the chances of success later in life. The first 1,000 days from conception to age two are increasingly being recognized as critical to the development of neural pathways that lead to linguistic, cognitive and socio-emotional capacities that are also predictors of labor market outcomes later in life. Poverty, malnutrition, and lack of proper interaction in early childhood can exact large costs on individuals, their communities and society more generally. The effects are cumulative and the absence of appropriate childcare and education in the three to five age range can exacerbate further the poor outcomes expected for children who suffer from inadequate nurturing during the critical first 1,000 days.

The Good News: ECD Interventions Are Effective

Research shows that there are large gains to be had from investing in early childhood development. For example, estimates place the gains from the elimination of malnutrition at 1 to 2 percentage points of gross domestic product (GDP) annually (World Bank, 2006). Analysis of results from OECD’s 2009 Program of International Student Assessment (PISA) reveals that school systems that have a 10 percentage-point advantage in the proportion of students who have attended preprimary school score an average of 12 points higher in the PISA reading assessment (OECD and Statistics Canada, 2011). Also, a simulation model of the potential long-term economic effects of increasing preschool enrollment to 25 percent or 50 percent in every low-income and middle-income country showed a benefit-to-cost ratio ranging from 6.4 to 17.6, depending on the preschool enrollment rate and the discount rate used (Lancet, 2011).

Indeed, poor and neglected children benefit disproportionately from early childhood development programs, making these interventions among the more compelling policy tools for fighting poverty and reducing inequality. ECD programs are comprised of a range of interventions that aim for: a healthy pregnancy; proper nutrition with exclusive breast feeding through six months of age and adequate micronutrient content in diet; regular growth monitoring and immunization; frequent and structured interactions with a caring adult; and improving the parenting skills of caregivers.

Related Content

Emily Gustafsson-Wright, Izzy Boggild-Jones, Sophie Gardiner

September 5, 2017

Brookings Institution, Washington DC

Tuesday, 3:00 pm - 5:30 pm EDT

The Reality: ECD Has Not Been a Priority

Yet despite all the evidence on the benefits of ECD, no country in the developing world can boast of comprehensive programs that reach all children, and unfortunately many fall far short. Programs catering to the very young are typically operated at small scale and usually through external donors or NGOs, but these too remain limited. For example, a recent study found that the World Bank made only $2.1 billion of investments in ECD in the last 10 years, equivalent to just a little over 3 percent of the overall portfolio of the human development network, which totals some $60 billion (Sayre et al, 2013).

The following are important inputs into the development of healthy and productive children and adults, but unfortunately these issues are often not addressed effectively:

Maternal Health. Maternal undernutrition affects 10 to 19 percent of women in most developing countries (Lancet, 2011) and 16 percent of births are low birth weight (27 percent in South Asia). Malnutrition during pregnancy is linked to low birth weight and impaired physical development in children, with possible links also to the development of their social and cognitive skills. Pre-natal care is critical for a healthy pregnancy and birth. Yet data from 49 low-income countries show that only 40 percent of pregnant women have access to four or more antenatal care visits (Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems, 2009). Maternal depression also affects the quality of caregiving and compromises early child development.

Child Care and Parenting Practices. The home environment, including parent-child interactions and exposure to stressful experiences, influences the cognitive and socio-emotional development of children. For instance, only 39 percent of infants aged zero to six months in low and middle-income countries are exclusively breast-fed, despite strong evidence on its benefits (Lancet, 2011). Also, in half of the 38 countries for which UNICEF collects data, mothers engage in activities that promote learning with less that 40 percent of children under the age of six. Societal violence and conflict are also detrimental to a child’s development, a fact well known to around 300 million children under the age of four that live in conflict-affected states.

Child Health and Nutrition. Healthy and well-nourished children are more likely to develop to their full physical, cognitive and socio-emotional potential than children who are frequently ill, suffer from vitamin or other deficiencies and are stunted or underweight. Yet, for instance, an estimated 30 percent of households in the developing world do not consume iodized salt, putting 41 million infants at risk for developing iodine deficiency which is the primary cause of preventable mental retardation and brain damage, and also increases the chance of infant mortality, miscarriage and stillbirth. An estimated 40 to 50 percent of young children in developing countries are also iron deficient with similarly negative consequences (UNICEF 2008). Diarrhea, malaria and HIV infection are other dangers with a deficit of treatment in early childhood that lead to various poor outcomes later in life.

Preprimary Schooling. Participation in good quality preprimary programs has been shown to have beneficial effects on the cognitive development of children and their longevity in the school system. Yet despite gains, enrollment remains woefully inadequate in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa. Moreover, national averages usually hide significant inequalities across socio-economic groups in access and almost certainly in quality. In all regions, except South Asia, there is a strong income gradient for the proportion of 3 and 4 year olds attending preschool.

Impediments to Scaling Up

So what are the impediments to scaling up these known interventions and reaping the benefits of improved learning, higher productivity, lower poverty and lower inequality for societies as a whole? There are a range of impediments that include knowledge gaps (especially in designing cost-effective and scalable interventions of acceptable quality), fiscal constraints and coordination failures triggered by institutional organization and political economy.

Knowledge Gaps . Despite recent advances in the area, there is still insufficient awareness of the importance of brain development in the early years of life on future well-being and of the benefits of ECD interventions. Those who work in this area take the science and the evaluation evidence for granted. Yet awareness among crucial actors in developing countries—policymakers, parents and teachers—cannot be taken for granted.

At the same time much of the evaluation evidence from small programs attests to the efficacy of interventions, we do not yet know whether large scale programs are as effective. The early evidence came primarily from small pilots (involving about 10 to 120 children) from developed countries. [1] ;While there is now considerable evidence from developing countries as well, such programs still tend to be boutique operations and therefore questions regarding their scalability and cost-effectiveness.

There are also significant gaps in our knowledge as to what specific intervention design works in which context in terms of both the demand for and the provision of the services. These knowledge gaps include the need for more evidence on: i) the best delivery mode – center, family or community based, ii) the delivery agents – community health workers, mothers selected by the community, teachers, iii) whether or not the programs should be universal or targeted, national or local, iv) the frequency and duration of interventions, of training for the delivery agents and of supervision, v) the relative value of nutritional versus stimulative interventions and the benefits from the delivery of an integrated package of services versus sector specific services that are coordinated at the point of delivery, vi) the most effective curricula and material to be used, vii) the relative effectiveness of methods for stimulating demand – information via individual contact, group sessions, media, conditional cash transfers etc. In all these design questions, cost-effectiveness is a concern and leads to the need to explore the possibility of building on an existing infrastructure. There is also a need for more evidence on the kinds of standards, training and supervision that are conducive to Safeguarding the quality of the intervention at scale.

Fiscal Constraints . Fiscal concerns at the aggregate level are also an issue and force inter-sectoral trade-offs that are difficult to make. Is it reasonable to expect countries to put money into ECD when problems persist in terms of both access and poor learning outcomes in primary schools and beyond? Even though school readiness and teacher quality may be the most important determinants of learning outcomes in primary schools, resource allocation shifts are not easy to make for policymakers. In addition, as discussed above, we do not yet have good answers to the questions around the cost implications of high quality design at scale.

Institutional Coordination and Political Context. Successful interventions are multi-sectoral in nature (whether they are integrated from the outset or coordinated at the point of delivery) and neither governments nor donor institutions are structured to address well issues that require cross-sectoral cooperation. When programs are housed in the education ministry, they tend to focus on preprimary concerns. When housed in the health ministry, programs ignore early stimulation. We do not know well what institutional structure works best in different contexts, including how decentralization may affect choices about institutional set ups.

There are also deeper questions about the nature of the social contract in any country that shapes views about the role of government and the distribution of benefits across the different segments of the population. Some countries consider that the responsibilities of the public sector start when children reach school age and view the issues around the development of children at a younger age to be the purview of families. And in many countries, policies that benefit children get short shrift because children do not have political voice and their parents are imperfect agents for their children’s needs. Inadequate political support then means that the legislative framework for early year interventions is lacking and that there is limited public spending on programs that benefit the young. For example, public spending on social pensions in Brazil is about 1.2 percent of GDP whereas transfers for Bolsa Familia which targets poor children are only 0.4 percent of GDP (Levy and Schady 2013). In Turkey, only 6.5 percent of central government funds are directed to children ages zero to 6, while the population above 44 receives a per capita transfer of at least 2.5 times as large as children today (World Bank, 2010). Finally, the long gestation period needed to achieve tangible results compounds the limited appeal of ECD investments given the short planning horizon of many political actors.

The Future: An Agenda for Scaling Up ECD

Addressing the constraints to scaling up ECD requires action across a range of areas, including more research and access to know how, global and country level advocacy, leveraging the private sector, and regular monitoring of progress.

Operational Research and Learning Networks. Within the EDC research agenda, a priority should be the operational research that is needed to go to scale. This research includes questions around service delivery models, including in particular their cost effectiveness and sustainability. Beyond individual program design, there are broader institutional and policy questions that need systematic assessment. These questions center on issues including the inter-agency and intergovernmental coordination modalities which are best suited for an integrated delivery of the package of ECD services. They also cover the institutional set-ups for quality assurance, funding modalities, and the role of the private sector. Finally, research is also needed to examine the political economy of successful implementation of ECD programs at scale.

Also necessary are learning networks that can play a powerful role in disseminating research findings and in particular good practice across boundaries. Many of the issues regarding the impediments for scaling up are quite context specific and not amenable to generic or off-the-shelf solutions. A network of peer learning could be a powerful avenue for policymakers to have deeper and face-to-face interactions about successful approaches to scaling up. South-South exchanges were an enormously valuable tool in the propagation of conditional cash transfer schemes both within Latin America and globally. These types of exchanges could be equally powerful for ECD interventions

Advocacy. There is a need for a more visible global push for the agenda, complemented by advocacy at country or regional levels and a strong role for business leaders. It should be brought to the attention of policymakers that ECD is not a fringe issue and that it is a matter of economic stability to the entire world. It is also in the interest of business leaders to support the development of young children to ensure a productive work force in the future and a thriving economy. Currently, there is insufficient recognition of the scale of the issues and the effectiveness of known interventions. And while there are pockets of research excellence, there is a gap in the translation of this work into effective policies on the ground. The nutrition agenda has recently received a great deal of global attention through the 1000 days campaign and the Scaling up Nutrition Movement led by the United States and others. Other key ECD interventions and the integration and complementarities between the multi-sectoral interventions have received less attention however. The packaging of a minimum set of services that all countries should aspire to provide to its children aged zero to six would be an important step towards progress. The time is ripe as discussions around the post-2015 development framework are in full swing, to position ECD as a critical first step in the development of healthy children, capable of learning and becoming productive adults.

Leveraging the Private Sector. The non-state sector already plays a dominant role in providing early childhood care, education and healthcare services in many countries. This represents both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is that the public sector typically lacks the capacity to ensure quality in the provision of services and research evidence shows that poor quality child care and education services are not just ineffective; they can be detrimental (Lancet 2011). The challenge is all the greater given that going to scale will require large numbers of providers and we know that regulation works better and is less costly in markets with fewer actors. On the opportunity side of the ledger, there is scope for expanding the engagement of the organized private sector. The private sector can contribute by providing universal access for its own workforce, through for-profit investments, and in the context of corporate social responsibility activities. Public-private partnerships can span the range of activities, including providing educational material for home-based parenting programs; developing and delivering parent education content through media or through the distribution chains of some consumer goods or even financial products; training preprimary teachers; and providing microfinance for home or center-based childcare centers. Innovative financing mechanisms, such as those in the social impact investing arena, may provide necessary financing, important demonstration effects and quality assurance for struggling public systems. Such innovations are expanding in the United States, paving the way for middle and low-income countries to follow.

ECD Metrics. A key ingredient for scaling up is the ability to monitor progress. This is important both for galvanizing political support for the desired interventions and to provide a feedback loop for policymakers and practitioners. There are several metrics that are in use by researchers in specific projects but are not yet internationally accepted measures of early child development that can be used to report on outcomes globally. While we can report on the share of children that are under-weight or stunted, we cannot yet provide the fuller answer to this question which would require a gauge of their cognitive and socio-emotional development. There are some noteworthy recent initiatives which will help fill this gap. The UNICEF-administered Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 4 includes an ECD module and a similar initiative from the Inter-American Development Bank collects ECD outcome data in a handful of Latin American countries. The World Health Organization has launched work that will lead to a proposal on indicators of development for zero to 3 year old children while UNESCO is taking the lead on developing readiness to learn indicators (for children around age 6) as a follow up to the recommendations of the Learning Metrics Task Force (LMTF) which is co-convened by UNESCO and the Center for Universal Education at Brookings.

The LMTF aims to make recommendations for learning goals at the global level and has been a useful mechanism for coordination across agencies and other stakeholders. A related gap in measurement has to do with the quality of ECD services (e.g., quality of daycare). Overcoming this measurement gap is critical for establishing standards and for monitoring compliance and can be used to inform parental decisions about where to send their kids.

ECD programs have a powerful equalizing potential for societies and ensuring equitable investment in such programs is likely to be far more cost-effective than compensating for the difference in outcomes later in life. Expanding access to quality ECD services so that they include children from poor and disadvantaged families is an investment in the future of not only those children but also their communities and societies. Getting there will require concerted action to organize delivery systems that are financially sustainable, monitor the quality of programming and outcomes and reach the needy.

Lancet (2007). Child development in developing countries series. The Lancet, 369, 8-9, 60-70, 145, 57, 229-42. http://www.thelancet.com/series /child-development-in-developing-countries.

Lancet (2011). Child development in developing countries series 2. The Lancet, 378, 1325-28, 1339- 53. http://www.thelancet.com/series/child-development-in-developing-countries-2.

Levy, S. and Schady, N. (2013). Latin America’s Social Policy Challenge: Education, social Insurance, Redistribution. Journal of Economic Perspectives 27(2) , 193-218.

OECD and Statistics Canada (2011). Literacy for Life: Further Results from the Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey. Paris/Ottawa: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development/Canada Minister of Industry.

Sayre, R.K., Devercelli, A.E., Neuman, M.J. (2013). World Bank Investments in Early Childhood: Findings from Portfolio Review of World Bank Early Childhood Development Projects from FY01-FY11. Draft, March 2013, Mimeo.

Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems (2009). More money for health, and more health for the money: final report. Geneva: International Health Partnership. http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net//CMS_files/documents/taskforce_report_EN.pdf

United Nations Children’s Fund (2005). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 3. UNICEF. http://www.childinfo.org/mics3_surveys.html.

United Nations Children’s Fund (2008). Sustainable Elimination of Iodine Deficiency: Progress since the1990 World Summit on Children. New York: UNICEF.

United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organization and The World Bank (2012). UNICEF- WHO-World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. New York: UNICEF; Geneva: WHO; Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

World Bank (2006). Repositioning Nutrition as Central to Development: A Strategy for Large-Scale Action. Directions in Development series. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

World Bank (2010). Turkey: Expanding Opportunities for the Next Generation- A Report on Life Chances. Report No 48627-TR. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

World Bank (2013). World Development Indicators 2013. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

[1] The Perry preschool and Abecedarian programs in the United States have been rigorously studied and show tremendous benefits for children in terms of cognitive ability, academic performance and tenure within the school system and suggest benefits later on in life that include higher incomes, higher incidence of home ownership, lower propensity to be on welfare and lower rates of incarceration and arrest.

Early Childhood Education Global Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Emily Gustafsson-Wright, Elyse Painter

September 25, 2024

June 20, 2024

Elyse Painter, Emily Gustafsson-Wright

January 5, 2024

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Development of Self-Regulation across Early Childhood

Janelle j montroy, ryan p bowles, lori e skibbe, megan m mcclelland, frederick j morrison.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence should be sent to Janelle J. Montroy, Children’s Learning Institute, Department of Developmental Pediatrics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 7000 Fannin Street Suite 2373H, Houston, TX 77030, USA. Tel: +1 713 500 3831. [email protected]

Issue date 2016 Nov.

The development of early childhood self-regulation is often considered an early life marker for later life successes. Yet little longitudinal research has evaluated whether there are different trajectories of self-regulation development across children. This study investigates the development of behavioral self-regulation between the ages of three and seven, with a direct focus on possible heterogeneity in the developmental trajectories, and a set of potential indicators that distinguish unique behavioral self-regulation trajectories. Across three diverse samples, 1,386 children were assessed on behavioral self-regulation from preschool through first grade. Results indicated that majority of children develop self-regulation rapidly during early childhood, and that children follow three distinct developmental patterns of growth. These three trajectories were distinguishable based on timing of rapid gains, as well as child gender, early language skills, and maternal education levels. Findings highlight early developmental differences in how self-regulation unfolds with implications for offering individualized support across children.

Keywords: Behavioral self-regulation, developmental trajectories, early childhood, longitudinal

The Development of Self-Regulation Across Early Childhood The development of effective self-regulation is recognized as fundamental to an individual’s functioning, with development during early childhood often considered an early marker for later life successes ( Blair, 2002 ; Bronson, 2000 ; Calkins, 2007 ; Diamond, 2002 ; Gross & Thompson, 2007 ; Kopp, 1982 ; McClelland & Cameron, 2012 ; Mischel et al, 2011 ; Moffitt et al., 2011 ; Vohs & Baumeister, 2011 ; Zelazo et al., 2003 ). Research indicates that between ages three and seven a qualitative shift in self-regulation may take place when children typically progress from reactive or co-regulated behavior to more advanced, cognitive behavioral forms of self -regulation (e.g., Diamond, 2002 ; Kopp 1982 ) that likely require the integration of many skills such as executive functions and language skills ( Calkins, 2007 ; Cole, Armstrong, & Pemberton, 2010 ). Likewise, past research suggests wide variation in the level of self-regulation skills children manifest during early childhood that consistently predicts a multitude of short- and long-term outcomes such as school readiness, academic achievement throughout primary school, adult educational attainment, feelings of higher self-worth, a better ability to cope with stress, as well as less substance use, and less law breaking, even among individuals at risk of maladjustment ( McClelland, Acock, Piccinin, Rhea, & Stallings, 2013 ; Mischel et al., 2011 ; Moffitt et al., 2011 ).

However, despite mounting evidence that early childhood is an important time period for the development of self-regulation, little is known about how children’s trajectories of development might vary across individuals over time ( Bergman, Magnusson, & Khouri, 2002 ; Muthén & Muthén, 2000 ; Nagin, 1999 ). To address this gap, we examined the inter-individual variation in children’s growth trajectories between preschool and early elementary school based on evidence that self-regulation requires the coordination and processing of multiple skills across several domains ( Calkins, 2007 ; Cole et al., 2010 ). More specifically, we posit that there will be differences related to when the integration of these skills begin to manifest as well as differences in the patterns of how they are manifest as regulated behavior ( Blair, 2010 ; Blair & Raver, 2012 ; 2015 ; Calkins, 2007 ; Clark et al., 2013 ). In the current study, we examined the development of behavioral self-regulation via the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders task ( Cameron et al., 2008 ) between the ages of three and seven with longitudinal data involving up to eight measurement occasions for individual children across three samples. We evaluated possible heterogeneity in the developmental trajectories of children’s behavioral self-regulation using growth mixture modeling (GMM; Grimm, McArdle, & Hamagami, 2007 ), and potential indicators of trajectory differences.

Defining Self-regulation

Self-regulation is a complex, multi-component construct ( Blair & Raver, 2012 ; McClelland, Cameron Ponitz, Messersmith, & Tominey, 2010 ; Schunk & Zimmerman, 1997 ; Vohs & Baumeister, 2011 ) operating across several levels of function (e.g., motor, physiological, social-emotional, cognitive, behavioral and motivational), that in its broadest sense represents the ability to volitionally plan and, as necessary, modulate one’s behavior(s) to an adaptive end ( Barkley, 2011 ; Gross & Thompson, 2007 ). One approach to the complexity of self-regulation has been to view the multiple functions of self-regulation as hierarchically organized and, eventually, reciprocally integrated ( Blair & Raver, 2012 ; Calkins, 2007 ). Ultimately self-regulation depends on the coordination of many processes across levels of function, with children’s ability to draw on, integrate, and manage these multiple processes increasing across developmental time ( McClelland & Cameron, 2012 ; McClelland et al., 2014 ).

The current study focuses on self-regulation in relation to its role in successful classroom functioning ( McClelland & Cameron, 2012 ; McClelland, Morrison, & Holmes, 2000 ; Nesbitt et al., 2015). Effective self-regulation in the classroom requires that the child seamlessly coordinate multiple aspects of top down control (i.e., executive function) such as attention, working memory, and inhibitory control along with motor or verbal functions to produce overt behaviors, such as remembering multi-step directions amidst distractions ( Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ; McClelland et al., 2007 ). This form of self-regulation is therefore typically termed behavioral self-regulation (c.f., emotional self-regulation; Gross & Thompson, 2007 ). To evaluate individual differences in development of self-regulation across multiple years, we used a well validated direct assessment of behavioral self-regulation, the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders task (HTKS, Cameron et al., 2008 ) that captures variations in behavioral self-regulation throughout the entire range of early childhood, making it possible to accurately assess developmental change on a common scale across time ( Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ; Connor et al., 2010 ; McClelland et al., 2007 ; Skibbe et al., 2012 ). The HTKS is a short, game-like task where children are asked to ‘do the opposite’ in regards to a set of paired rules. For example, if the child is asked to touch their head, instead they must touch their toes. This task taps three executive function skills ( McClelland et al., 2014 ) in order to make a gross motor response: 1. attention (ability to focus on instructions and current stimuli), 2. working memory (ability to process the current trial while holding a rule or set of rules in mind), and 3. inhibition (ability to ignore a well learned response in order to respond in a counter-intuitive way).

Executive functions help an individual understand, monitor, and control their own reaction to the environment, as well as problem solve regarding desired future behaviors and/or outcomes. Put another way, the coordination of these skills often forms the basis of a child’s ability to respond adaptively within the classroom. Notably a distinction has been made in recent years between executive functions at the service of abstract or decontextualized environments, and executive functions at the service of adapting to environments that require the regulation of affect and motivation (e.g., Hongwanishkul et al., 2005). Sometimes referred to as ‘cool’ executive functions and ‘hot’ executive functions within cognitive traditions (e.g., Zelazo & Carlson, 2008 ), these skills can be considered as necessary (although not entirely sufficient; Ursache & Blair, 2011) for behavioral and emotional aspects of self-regulation, respectively (Zhou & Chen, 2008). Both hot and cool aspects are important for development; hot aspects are usually more associated with socio-emotional health and outcomes, while cool aspects are more associated with cognitive and academic outcomes ( Kim et al, 2013 ). The HTKS task generally draws on cool aspects of executive function, although in reality no task is entirely free of an emotional context, with distinctions generally being a matter of degree (Manes et al, 2002).

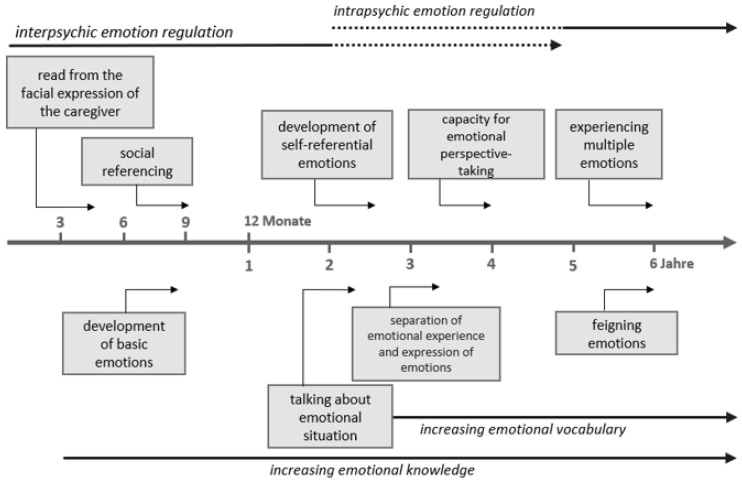

The Development of Behavioral Self-regulation

The development of self-regulation begins in infancy, with many of the skills that are important for behavioral self-regulation developing first as separate domains, then becoming organized and integrated over time ( Barkley; 2011 ; Corrigan, 1981 ; Diamond et al., 1997 ; Kopp, 1989 ; Stifter & Braungart, 1995 ). Previous work indicates that not only do separate facets of self-regulation appear to develop at different times and rates (such as emotional self-regulation generally preceding the development of behavioral self-regulation; Howse et al., 2003 ) but also the underlying skills may also develop at different times. For example, the ability to delay a response (an outcome most strongly associated with developing inhibitory control) appears to develop earlier than other executive skills ( Lengua, et al., 2015 ). However, despite differences across individual facets and skills associated with self-regulation, previous research consistently indicates that children younger than three have difficulty simultaneously coordinating and utilizing multiple executive function skills to create a behavioral response that also requires a motor or verbal action ( Carlson, Moses, & Breton, 2002 ; Diamond, 2002 ; Zelazo et al., 2003 ). However, after age three and during early childhood, the individual skills that support behavioral self-regulation (e.g., see Cole et al., 2010 ; Diamond et al., 1997 or Rothbart et al., 2006 ), as well as behavioral self-regulation itself as an integration of those skills, rapidly develop(s), signifying a qualitative shift in children’s regulatory abilities ( Best & Miller, 2010 ; Garon et al., 2008 ; Kopp, 1982 ; Zelazo et al., 2008 ).

Specifically, cross sectional work with a multitude of tasks indicates a rapid increase or “leap” in performance on tasks that require the integration of several executive function skills into behavior, such as the HTKS task, the Dimensional Change Card Sort, The Day/Night, Bear/Dragon, Fish Flanker, and Luria’s tapping task ( Diamond, 2002 ; Gerstadt et al., 1994 ; Rothbart et al., 2006 ; Rueda et al., 2004 ; Zelazo et al., 2003 ). For example, there are large group differences in accuracy on a fish flanker task (see Rueda et al., 2004 for a description of the task) between four year olds and six year olds, but by about age seven, children’s accuracy gains level off as performance becomes similar to adults (although reaction time continues to improve; Rothbart et al., 2006 ; Rueda et al., 2004 ). In addition, recent work explicitly evaluating behavioral self-regulation longitudinally ( Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ), as well as several studies of underlying executive function skills ( Chang, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner & Wilson, 2014 ; Clark et al., 2013 ; Diamond et al., 1997 ; Wiebe, Sheffield & Espy, 2012) indicate non-linear growth with rapid gains followed by a decelerating rate of gain in performance.

In summary, theory and research both provide evidence of rapid gains in the ability to regulate behavior that are likely linked to the integration of multiple processes, but particularly processes considered under the umbrella of executive function, such as attention, working memory and inhibition ( Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ; Chang et al., 2014 ; Diamond, 2002 ; Rothbart, et al., 2006 ). Based on these findings, we expect that the development of behavioral self-regulation in early childhood is likely best represented by a nonlinear function ( Diamond, 2002 ). Specifically, we expect that between the ages of three and seven years, gains in self-regulation will increase rapidly as multiple processes become more coordinated, followed by later decelerated growth (e.g., Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ; Chang et al., 2014 ; Wiebe et al., 2012).

Heterogeneity in behavioral self-regulation development

Several prominent theories suggest the possibility of multiple self-regulation growth trajectories across early childhood (see Blair, 2010 ; Blair & Raver, 2012 ; 2015 ; Calkins, 2007 ; Lerner & Overton, 2008 ). Specifically, theories drawing on psychobiological or dynamic systems models ( Blair & Raver, 2015 ; Lerner & Overton, 2008 ) indicate a back and forth developmental relationship between children’s biological traits and their experiences. These theories contend that how children learn to regulate their behavior can vary widely given that biological predispositions such as temperament and early environmental experiences greatly vary. However, few studies have fully tested whether there are underlying trajectory differences in self-regulation such that children develop behavioral self-regulation in differing ways (i.e., process differences) and/or at different rates ( Posner & Rothbart, 2000 ; Rothbart, Ellis, Rueda & Posner, 2003 ). The majority of work in this area has noted mean differences in the amount of self-regulation children are able to exert at a given age during early childhood; only recently have studies begun to focus on growth in self-regulation and predictors thereof. Of these studies, few have accounted for systematic inter-individual differences across time (but see Vallotton & Ayoub, 2011 ; Wanless et al., 2016 ; Willoughby et al., 2016 ).

Instead, the majority of studies evaluating self-regulation growth have focused on utilizing child and environmental aspects to predict aggregate variation around a general slope and/or rate mean (e.g., Blandon et al., 2008 ; Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ; Clark et al., 2013 ), without further consideration for whether this variation may indicate qualitatively distinct developmental change. This makes it is difficult to conclude whether there actually are subgroups of children with systematic differences in how self-regulation processes unfold ( Rogosa, 1988 ). Likewise, findings at the aggregate level do not necessarily describe the relationship among variables for a single individual or subgroup of individuals ( von Eye & Bergman, 2003 ). This makes it equally difficult to accurately map out predictive relations between children’s individual traits and environments and their self-regulation development.

Only one study to date has evaluated multiple trajectories across children in behavioral self-regulation ( Wanless et al., 2016 ). This studied focused specifically on a Taiwanese sample of children and indicated two distinct behavioral self-regulation trajectories: an “increasing” developers trajectory with children rapidly gaining in self-regulation and then leveling off across early childhood, and a “steady-then-increasing” trajectory with children demonstrating few regulatory gains between ages 3 – 5 years and rapid gains after 5 years of age. However, this study only includes a relatively small sample, and focuses on a homogenous population in Taiwan.

The current study builds upon and extends this previous work by directly examining the possibility of qualitatively different behavioral self-regulation growth trajectories between the ages of three and seven in a large heterogeneous population. We focus specifically on behavioral self-regulation as theoretical considerations indicate that the regulation of behavior is expected to include multiple trajectories during early childhood given that the multiple executive function inputs that support it are sensitive to not only genetic inputs but experiential inputs and that these inputs are rapidly developing and differentiating during this time period ( Blair & Raver, 2012 ; Lonigan & Allan, 2014). As part of investigating potential trajectories, we also evaluate one rough environmental proxy and two child level predictors in order to validate potential trajectory differences, and better understand patterns of how and, possibly when, these factors matter for self-regulation development across children.

Child factors

There are several early characteristics that previous studies have identified as having an association with the development of behavioral self-regulation ( Blair et al., 2011 ; Calkins, Dedmon, Gill, Lomax, & Johnson, 2002 ; Cole et al., 2010 ; Matthews et al., 2009 ). The current study focuses on children’s gender and language skills as these attributes are fairly consistently linked to individual differences in self-regulation ( Bohlmann et al., 2015 ; Matthews et al., 2009 ; Ready et al., 2005 ), and potentially trajectory differences ( Vallotton & Ayoub, 2011 ).

Previous findings generally indicate that boys have lower levels of self-regulation than girls ( Kochanska et al., 2001 ; Matthews et al., 2009 , 2014 ; McClelland et al., 2007 ), with gender differences often increasing across time ( Matthews et al., 2014 ). It is not well understood why such gender differences occur (though see Entwistle, Alexander, & Olson, 2007 ), although recent work suggests gender differences may in part relate to cultural beliefs and expectations ( von Suchodoletz et al., 2013 ; Wanless et al., 2016 ). However, there is evidence that, from an early age, gender is associated with what type of self-regulation developmental trajectory a child is likely to follow ( Vallotton & Ayoub, 2011 ). For example, during toddlerhood, boys’ self-regulation generally dips around age two then rises, while girls’ self-regulation rises steadily, resulting in gender differences at ages two and three favoring girls. Additional research focused on kindergarteners suggests that a subset of boys persist in demonstrating very low levels of behavioral self-regulation ( Matthews et al., 2009 ), potentially signifying these boys not only continue to developmentally lag behind girls, but that they may also not be acquiring self-regulation in the same way that peers are. Given these past findings, we expected that boys may be more likely to follow a potentially lagged trajectory.

Language is another child attribute that affects developing self-regulation, and may be an important factor for understanding potential self-regulation trajectory differences across children. Theoretically, language is thought to give children “mental tools” to help them organize and modify their thoughts and behaviors ( Vygotsky, 1934/1986 ). During early childhood, expressive language in particular may be important as it enhances the ability of the child to both name their own current state and manipulate that state in relation to a specific context ( Cole et al., 2010 ). It also seemingly enhances children’s ability to hold task requirements in mind (Karbach, Eber, & Kray, 2008). Research evaluating how expressive language helps toddlers to self-regulate suggests that trajectories of self-regulation vary between children based on the child’s observed expressive vocabulary skills ( Vallotton & Ayoub, 2011 ). Likewise, early expressive language skills are also associated with higher levels of early self-regulation, with greater language gains across preschool and the transition to kindergarten associated with greater self-regulation gains ( Bohlmann, Maier, & Palacios, 2015 ). This suggests that children with higher levels of expressive language develop self-regulation faster compared to children with lower levels of language. We also expected expressive language to be related to self-regulation growth on the HTKS because children use both expressive and receptive language when completing the task (and can answer verbally if needed/verbalize actions). Based on these previous findings, the pattern of associations between expressive language at the start of schooling and potential self-regulation trajectories should follow a similar pattern such that lower levels of expressive language are associated with a distinct, potentially lagged trajectory compared to higher levels of expressive language.

Mother education

In addition to child attributes and competencies, past research consistently demonstrates that children’s environments affect developing behavioral self-regulation ( Blair, 2010 ; Grolnick & Farkas, 2002 ; Landry et al., 2006 ). One particularly salient aspect of children’s environments that may affect developing self-regulation is their mothers’ education levels (e.g., see Miech, Essex, & Goldsmith, 2001 ). Mother education often serves as a rough yet important proxy of family socioeconomic status and resources ( Bradley & Corwyn, 2002 ; Hoff, Laursen & Tardif, 2002 ). Low maternal education levels have been linked to lower socioeconomic resources and higher stress levels that, over time, can affect children’s developing neuroendocrine processes (e.g., such as cortisol levels). These processes are theorized to directly shape developing self-regulatory response patterns (see Blair & Raver, 2015 ). Maternal education levels are also associated with distinct parenting profiles that include mothers’ warmth, responsiveness, use of rich language inputs, and ability to maintain their children’s attention ( Guttentag, Pedrosa-Josic, Landry, Smith & Swank, 2006 ), all factors that predict individual differences in children’s self-regulation levels (see Grolnick & Farkas, 2002 ). Thus, mother education levels are also expected to serve as indicator of valid differences in children’s developing self-regulation patterns.

Current Study

Past theory and research indicate that behavioral self-regulation rapidly develops during early childhood with possible heterogeneity of early self-regulation trajectories (e.g., Blair & Raver, 2015 ; Vallotton & Ayoub, 2011 ; Wanless et al., 2016 ). To better understand behavioral self-regulation development and heterogeneity across children, we used the HTKS measure to assess and evaluate development via latent growth curve modeling. We then directly focused on potential trajectory differences in early childhood utilizing growth mixture modeling. We hypothesized that most children would demonstrate rapid gains in their behavioral self-regulation trajectory (e.g., Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ; Matthews et al., 2009 ), compared to peers, with these gains occurring early in schooling ( Blair & Raver, 2015 ). However, we hypothesized a subset of children would demonstrate a lagged behavioral self-regulation trajectory across early childhood as they are not ready to integrate the multiple processes required by advanced behavioral self-regulation when they first reach school ( Wanless et al., 2016 ; Willoughby et al., 2016 ). As part of trajectory validation, we utilized multiple diverse samples that included the same measure of behavioral self-regulation within similar age ranges, and with similar data collection procedures in order to evaluate whether trajectory findings replicate across a diverse population of children in different areas of the United States. We then further validated trajectories in relation to predicted associations between three characteristics: gender, language ability, and maternal education levels. We expected that these factors would distinguish what trajectory a child was likely to follow, with patterns of association matching previous findings, offering evidence indicating that trajectories capture meaningful individual difference as well as increasing our understanding how these characteristics relate to individual differences in development over time.

Participants

Participants consisted of 1,386 children across three samples that had at least two assessments of self-regulation between the ages of three and seven. Children were administered the same direct assessment of behavioral self-regulation in all three studies (the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders Task; Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ). The samples are described below.

Michigan longitudinal sample

The first sample was collected in predominantly middle- to upper-SES suburban area with a range of ethnic diversity in southeast Michigan. Participants included 351 (51% female) children followed from preschool through second grade as part of the “Pathways to Literacy” longitudinal study evaluating children’s socio-emotional and cognitive development (e.g., ***; blinded for review; 32 of the full sample of 383 were not included due to having fewer than 2 assessments of self-regulation). Students attended 314 classrooms located within 16 schools in a single suburban school district. All schools within this district that included at least one preschool classroom were represented and preschool classrooms included Head Start classrooms ( n = 49) as well as those that charged tuition. On average, children were 48.16 months ( SD = 7.35) old at the start of the study: just over four years of age. The bulk of parents who provided information about their child’s ethnicity ( n =257) reported that their child was White/Caucasian (80%). The remainder of children were described as African-American (4%), Asian/Indian ( 5% ), Hispanic (1%), and Multi-racial (3%). Several parents (8%) noted that another ethnicity would describe their child best. Most ( n = 278) families noted that their child’s native language was English, although some families ( n = 73) did not respond to this question 1 . Median household income was high (i.e., $115,000; Range = $11,000 to $650,000) as were parent education levels, with over 75% of mothers (n = 233) reporting that they had earned at least a bachelor’s degree.

Families were recruited via flyers sent home in children’s backpacks at the beginning of the school year(s). Children’s self-regulation was evaluated in the fall and spring of each year that the child was in the study until they finished first grade (up to 8 times) as part of a battery of measures administered by trained research assistants. Language assessments were administered during the fall of children’s first preschool year. Parents also filled out demographic information including child gender and information related to education level in the fall of their child’s first preschool year.

MLSELD preschool sample

The second sample consisted of 642 (51% female) preschool aged children from middle-SES communities with data waves collected over four years in Michigan as part of the Michigan Longitudinal Study of Early Literacy Development (MLSELD preschool sample; ***; blinded for review). Children were drawn from 78 classrooms across six schools: two in central Michigan and four in western Michigan. Schools in central Michigan were accredited by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. One was associated with a university and the other was a joint public/university preschool that also had a population of Head Start eligible children (less than 5% of the current sample). The four schools in western Michigan were part of the area’s public schools. In western Michigan, families were recruited for participation at a parent information night, while at the central Michigan schools families were recruited via flyers sent home in children’s backpacks. Children were on average approximately four years of age at the start of the study ( M = 47.74, SD = 7.02). Most parents who provided information about their child’s ethnicity ( n = 479) reported that their child was White/Caucasian (81%). Children who were African American (2%), Hispanic (3%), Asian (7%), multi-racial (4%), and those from ‘other’ (3%) ethnicities also participated in the present work. Among families reporting primary language spoken at home, almost all reported English ( n = 443) although some families did not respond to this question ( n = 158). Over half of mothers ( n = 374) reported that they had earned at least a bachelor’s degree. Household income levels were not collected as part of this study.

Children’s self-regulation was collected in the fall and spring of each year by a trained research assistant in a quiet setting; self-regulation was also collected two additional times in winter (about a month and a half apart) in two years of the study, and one additional time in the winter in one year of study (i.e., in the first two years of study self-regulation was assessed four times, year three it was assessed three times, and it was assessed twice in year four). Children’s language skills were tested in the fall of their first year of preschool and parents filled out demographic information including child gender and information related to education level at this time as well. Some children ( n = 160) participated in the study over the course of two years and a small subset of children ( n = 13) were included in the study for three years. Thus these children had their self-regulation evaluated more frequently. Across the larger MLSELD study ( n = 888), 246 children either had only one self-regulation assessment ( n = 133) or no assessments ( n = 113; by design, only half of the sample had self-regulation assessed in year 4).

Oregon sample

The third sample was recruited from a mixed-SES rural site in Oregon and consisted of 393 (50% female) children followed from preschool through kindergarten as part of a measurement study focused on improving measures of school readiness and self-regulation (***; blinded for review; 38 of the full sample of 431 were not included due to having fewer than 2 assessments of self-regulation related to study attrition). Children were drawn from 37 classrooms in 17 schools, with 54% ( n = 209) of children in Head Start programs. Children were on average over four and a half years old at the start of the study ( M = 56.14, SD = 3.65). Most parents who provided information about their child’s ethnicity ( n = 354) reported that their child was White/Caucasian (63%), or Hispanic (19%). Children who were African American (1%), Asian/Pacific Islander (4%), multi-racial (13%), and those from ‘other’(1%) ethnicities also participated in the present work. Families reported that English was the primary language spoken at home for most children ( n = 297); however this sample also included a subsample of children whose primary language was Spanish ( n = 60) who were tested in Spanish (all Spanish speakers were enrolled in Head Start). On average, mothers reported having attended some college, but only 43% reported that they had earned a bachelor’s degree or higher. Of respondents, 58% indicated that their families qualified for public assistance such as WIC or food stamps in the past four years.

Families were recruited through letters sent home with an enrollment packet sent during the summer before the beginning of the preschool year. Self-regulation was assessed each year in the fall and spring by trained research assistants (up to four time points). Language skills were assessed in the fall of children’s preschool year, and parents filled out demographic surveys at this time.

Self-regulation

Children’s self-regulation was measured directly using the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders task ( Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ; Connor et al., 2010 ; Matthews, et al., 2009 ). During the task, children are provided with paired behavioral rules (e.g., touch your head/touch your toes) and asked to do the opposite of what they were instructed to do. For example, when a child is asked to touch her toes, she should complete the opposite action (touch her head). The first ten items include one paired rule (e.g., head/toe). If children respond correctly to four or more items, they are given ten additional items with two paired rules (e.g., head/toes, knees/shoulders). Children earned two points for each correct response, one point for each self-correction (i.e., an initial movement to the incorrect response, but ultimately ending with the correct response), and zero points for each incorrect response. Scores ranged from 0–40, with higher scores indicating higher self-regulation. In the first year of the Michigan longitudinal sample data collection, when all children were in preschool, only the first half of the HTKS was administered, as the second half had not yet been developed. We therefore used a Rasch measurement approach to extrapolate an expected score on the entire 40 item task (details are provided in Bindman, Hindman, Bowles, & Morrison, 2013 ).

The HTKS has good construct and predictive validity within many culturally diverse samples, and across languages ( Cameron Ponitz, McClelland, Matthews, & Morrison, 2009 ; McClelland et al., 2007 ; von Suchodoletz et al., 2013 ; Wanless, et al., 2011 ). Scores on this measure are significantly correlated with reported self-regulation in the classroom, parental reports of attention ( Cameron Ponitz et al., 2009 ; McClelland et al., 2007 ) and other measures of self-regulation and executive function tasks. The HTKS also loads well onto a self-regulation factor with other similar measures ( Allan & Lonigan, 2014 ). In addition, past evidence indicates that growth in HTKS performance does not appear to be a function of practice effects ( Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ).

In terms of predictive validity, the HTKS consistently predicts academic achievement across diverse sample populations ( McClelland et al., 2007 ; Montroy et al., 2014 ; von Suchodoletz et al., 2013 ; Wanless et al., 2011 ). Notably, evidence suggests HTKS scores and growth are generally stronger predictors of growth in academic achievement than other self-regulation and executive function measures, particularly measures that mostly capture one skill versus an integration of skills ( Lipsey et al., 2014 ; McClelland et al., 2014 ).

The HTKS has strong reliability ( Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ; Matthews et al., 2009 ; Montroy, et al., 2014 ; Wanless, et al., 2011 ). Past studies consistently report high levels of inter-rater reliability (kappa > .90; Cameron Ponitz et al., 2008 ), and internal consistency estimates above .80 ( Montroy et al., 2014 ; Wanless et al., 2011 ). Within the current study internal consistency was also good, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .85–.94 across samples.

Language skills were assessed across all three samples. In the Michigan longitudinal sample and the Oregon sample, the Picture Vocabulary subtest of the Woodcock Johnson III was used as an indicator of language ( Woodcock & Mather, 2001 ), while the Test of Preschool Early Literacy picture vocabulary subtest (TOPEL; Lonigan, Wagner, Torgeson, & Rashotte, 2007 ) was used in the MLSELD preschool sample. Both the TOPEL and WJ vocabulary tests have been well validated and extensively used in the literature as indicators of expressive vocabulary ( Bohlmann et al., 2015 ; Pence, Bojczyk & Williams, 2007; Wilson & Lonigan, 2009 ; Vallotton & Ayoub, 2011 ).

The Woodcock Johnson picture vocabulary subtest is an untimed picture naming task where children are shown a series of pictures and are asked to verbally identify the image. Children speaking Spanish in the Oregon sample were administered the Picture Vocabulary subtest of the Spanish version of the Woodcock-Johnson, the Bateria III Woodcock-Munoz. Picture Vocabulary has strong evidence of reliability (e.g., split half reliability between 0.76–0.81 for English speaking children and 0.88–0.89 for Spanish speakers) and validity. We used W-scores, a Rasch-type measure of ability, for all analyses. This type of score ensures measurement on an equal-interval scale and takes into account the level of item difficulty in relation to a children’s age.

The TOPEL picture vocabulary subtest consists of 35 items including various untimed picture naming tasks where children name pictures (1 point) and then describe aspects or functions associated with the picture presented to them (e.g., What are they for? 1 point) 2 . Thus raw scores range from 0–70. Test-retest reliability for this subtest is .81 and test developers indicated that scores were strongly related to the Early One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test ( r = .71, Brownell, 2000 ). The TOPEL was administered only in years 2 and 3 of the study. The remaining n =77 in year 1 and n = 113 in year 4 were not administered by design.

Mother education and gender

Across samples, demographics questionnaires were provided to parents including information regarding the child’s gender and parent education levels. For the Michigan longitudinal and the Oregon sample, mothers were asked to report education in terms of the number of years of schooling they had completed, while the MLSELD preschool sample was asked to report education levels via an 11-point survey question where education level categorically increased with 1 = less than a high school level education, 7 = a bachelor’s degree, and 11 = an advanced graduate degree (e.g., Ph.D or M.D). For comparability across samples, data from the Michigan longitudinal and Oregon sample were converted to the 11-point scale used by the MLSELD sample.

Analytic Approach

Analyses were done in two parts to (1) describe the general growth trajectory of self-regulation and (2) evaluate heterogeneity in self-regulation trajectories across children. First, we used latent growth curve models ( Bowles & Montroy, 2013 ; McArdle, 1986 ; Meredith & Tisak, 1990 ; Singer & Willett, 2003 ) to examine the general trajectory of development of self-regulation. These models provide information about the average values of children’s self-regulation (level of self-regulation) at a specified time, how rapidly their skills increase or decrease (i.e., slope), and whether this change is constant or might accelerate or decelerate (i.e., linear versus nonlinear growth). The general equation for the latent growth curve models we used was:

where Self-reg [ t ] n is the HTKS score for child n at age t; A[t] or the basis coefficient(s), are a function defining the shape of the growth trajectory, determining both the precise interpretation of the Level and the Slope , and the nature of change; Level n represents child n’s predicted level of self-regulation at the point where A[t] is 0; and Slope n generally reflects child n’s predicted rate of growth on the HTKS per unit of the basis coefficients. We considered five models for the trajectory: linear, quadratic, exponential, logistic, and the latent basis model. Due to variation in what age children received assessments and the time between assessments, scores were grouped by child age into three month windows in each dataset 3 . To evaluate what model optimally described the general growth trajectory of behavioral self-regulation, we utilized the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC) fit indices.

Next, we utilized growth mixture modeling (GMM; Muthén, 2001 ) to evaluate if there were multiple growth trajectories of early childhood behavioral self-regulation. In GMM, the trajectory classes are formed based on the growth factor means and variances (e.g., Level and Slope means and variances) with each class defining a different growth trajectory ( Muthén, 2001 ). GMM also captures individual variation around these growth curves by estimating the growth factor variances within each class ( Muthén & Muthén, 2000 ). Within the GMM models, we chose to restrict trajectory shape to the shape indicated by the latent growth curve models. This is common practice in the GMM literature when there is not a strong theory regarding shape of trajectory differences across the population. However, slope and rate parameters (but not functional form) were ultimately allowed to vary across trajectories, thus providing information regarding different developmental progressions and patterns. In all models, errors were specified to be uncorrelated. We determined best model fit based on AIC and aBIC indices ( Tofighi & Enders, 2007 ), entropy, and bootstrapped likelihood ratio tests (BLRT) which compares the fit of the estimated model with k classes to the same model with one less class (k-1), with p-values less than .05 indicating that the estimated k class model fits better than the k-1 model ( Grimm, Ram & Estabrook, 2010 ). Note, BLRTs can only test differences in relation to what number of classes fits best, they provides little information when comparing within class solutions with differing parameters (e.g., whether a solution with constrained random effects versus variable random effects fit best). In addition we also considered whether results were interpretable and meaningful, and we took into account estimation parameters as well as estimation history as these are all relevant indicators of model comparison and selection ( Grimm et al., 2010 ). To evaluate the predictors of trajectory classes, we assigned each child to the class with the highest probability, and used logistic regression based analyses to predict class membership 4 . All analyses were completed with Mplus version 7.2 ( Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010 ), utilizing full information maximum likelihood to account for missing data. In all analyses, year of study was included as a saturated covariate given its relationship with missing data in all samples, and the MLR estimator was used as this estimator provides the most accurate parameter estimates when missing data are present ( Enders, 2010 ; Graham, 2003 ).

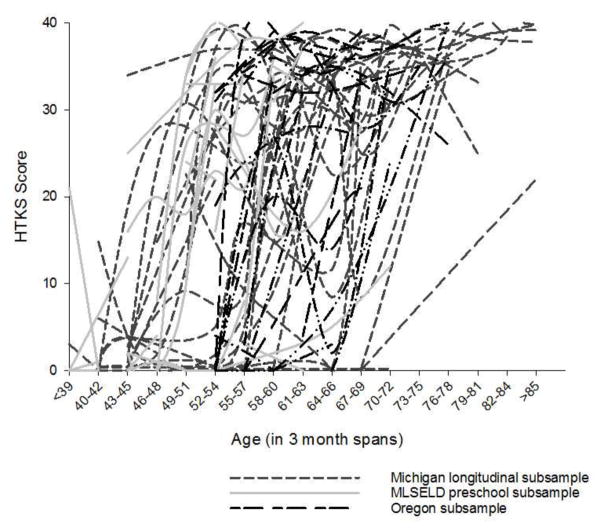

Descriptive Statistics of Behavioral Self-regulation

On average, children demonstrated gains in behavioral self-regulation as measured by the HTKS between the ages of three and seven; see Table 1 for a comparison of average gains across samples. Individual observed trajectories for a random subset of 25 children’s scores per sample are presented in Figure 1 . In all samples, there were substantial individual differences, and periods of acceleration and deceleration in growth both within and across children. Correlations are provided in the supplementary materials .

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Self-regulation by Sample and Age.

| Variable | Michigan longitudinal | MLSELD preschool | Oregon | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | N | M | SD | |

| -HTKS age 39 mos. or less | - | - | - | 103 | 3.66 | 7.70 | - | - | - |

| -HTKS age 40 – 42 mos. | 98 | 4.98 | 8.92 | 128 | 5.50 | 9.95 | - | - | - |

| -HTKS age 43 – 45 mos. | 101 | 8.92 | 12.26 | 144 | 7.25 | 11.38 | - | - | - |

| -HTKS age 46 – 48 mos. | 111 | 12.95 | 14.81 | 185 | 9.15 | 11.32 | - | - | - |

| -HTKS age 49 – 51 mos. | 111 | 18.21 | 15.16 | 241 | 11.95 | 13.49 | - | - | - |

| -HTKS age 52 – 54 mos. | 153 | 20.48 | 15.22 | 276 | 16.73 | 14.27 | 157 | 12.44 | 13.11 |

| -HTKS age 55 – 57 mos. | 151 | 21.67 | 14.58 | 293 | 17.63 | 14.86 | 161 | 16.53 | 13.32 |

| -HTKS age 58 – 60 mos. | 152 | 25.19 | 13.46 | 217 | 22.78 | 14.28 | 201 | 18.74 | 14.20 |

| -HTKS age 61 – 63 mos. | 128 | 28.29 | 10.61 | 165 | 25.28 | 14.01 | 186 | 21.78 | 14.40 |

| -HTKS age 64 – 66 mos. | 140 | 29.51 | 10.78 | - | - | - | 174 | 23.15 | 13.54 |

| -HTKS age 67 – 69 mos. | 154 | 31.20 | 8.90 | - | - | - | 140 | 26.61 | 13.01 |

| -HTKS age 70 – 72 mos. | 110 | 33.49 | 6.97 | - | - | - | 162 | 28.85 | 10.47 |

| -HTKS age 73 – 75 mos. | 108 | 35.58 | 4.85 | - | - | - | 97 | 30.32 | 11.84 |

| -HTKS age 76 – 78 mos. | 118 | 35.37 | 5.31 | - | - | - | 95 | 30.47 | 10.61 |

| -HTKS age 79 – 81 mos. | 113 | 37.05 | 3.08 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| -HTKS age 82 – 84 mos. | 80 | 36.60 | 4.56 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| -HTKS age 85 mos. or more | 61 | 37.55 | 3.30 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Note. HTKS refers to the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders task. Mos. refers to months. Dashes represent ages that data were not collected by sample.

Random subset of 25 children per sample’s (75 total) smoothed behavioral self-regulation trajectories

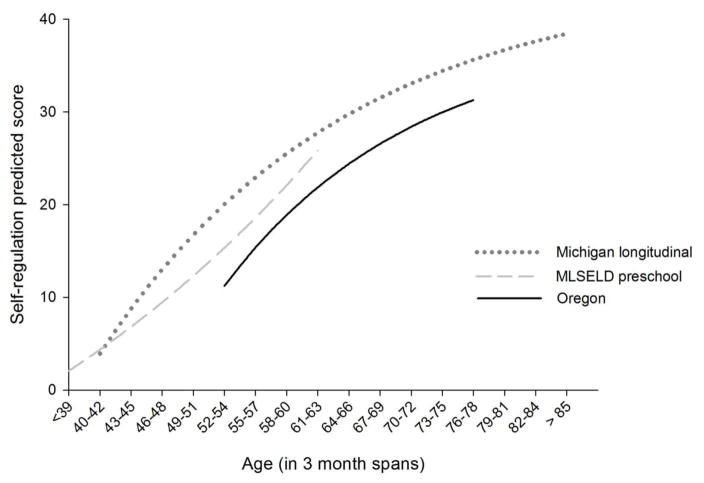

Fit statistics for the five latent growth curve models are reported in Table 2 by sample. In all samples, both AIC and aBIC suggested that the changes and between person differences in early childhood behavioral self-regulation development were best described by an exponential curve; see Figure 2 . Across samples patterns varied such that: in the MLSELD preschool sample, children’s growth accelerated across preschool. However, in the Oregon and Michigan longitudinal samples that followed children across early elementary grades, children demonstrated faster gains early in preschool with gains slowing in early elementary school 5 .

Table 2. Summary of Latent Growth Model Fit Statistics.

| Models | -2 Log Likelihood | Free parameters | AIC | aBIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michigan longitudinal sample | ||||

| - Linear | 7071.40 | 6 | 14154.81 | 14158.94 |

| - Quadratic | 6961.99 | 10 | 13943.97 | 13950.86 |

| - Modified logistic | 7024.69 | 8 | 14065.38 | 14070.88 |

| - Latent basis | 7184.79 | 19 | 14407.57 | 14420.65 |

| - Exponential | 6934.36 | 10 | ||

| MLSELD preschool sample | ||||

| - Linear | 6688.04 | 6 | 13588.08 | 13595.82 |

| - Quadratic | 6760.81 | 10 | 13541.63 | 13554.52 |

| - Modified Logistic | 6783.97 | 8 | 13583.95 | 13594.26 |

| - Latent Basis | 6779.69 | 13 | 13585.38 | 13602.14 |

| - Exponential | 6760.21 | 10 | ||

| Oregon sample | ||||

| - Linear | 5216.08 | 6 | 10444.16 | 10448.97 |

| - Quadratic | 5192.96 | 10 | 10405.91 | 10413.92 |

| - Modified logistic | 5208.42 | 8 | 10432.85 | 10439.25 |

| - Latent basis | 5202.44 | 13 | 10430.88 | 10441.29 |

| - Exponential | 5189.12 | 10 | ||

Note. AIC refers to the Akaike information criterion, aBIC refers to the adjusted Bayesian information criterion. Bolded values indicate best fit.

Latent growth curve model of the developmental trajectory of behavioral self-regulation by sample.

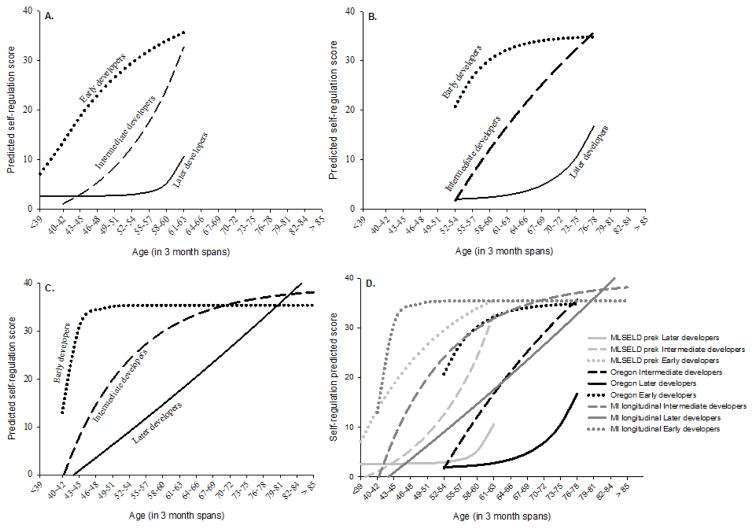

Heterogeneity in Behavioral Self-regulation Development