An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Publishing Industry: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Scientific Production Indexed in Scopus

Marta magadán-díaz, jesús i rivas-garcía.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2022 Aug 16; Issue date 2022.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted research re-use and secondary analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the World Health Organization (WHO) declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic.

The general goal of this work is to carry out a bibliometric analysis of the scientific production in the publishing industry between 2012 and 2022. For this purpose, the following research posed the following questions: (i) what are the leading academic publications that collect scientific production around the publishing industry? (ii) who are the most productive and influential authors in research on the publishing industry? (iii) from which countries do the published academic works come?, and (iv) in which universities are research on the publishing industry concentrated? This research used the information available in Scopus to address this bibliometric analysis. The analysis conducted in this work is exploratory, descriptive, and quantitative, based on the techniques and tools of bibliometric analysis of the documents stored in the Scopus bibliographic database. This article highlights that research on the global book publishing market is interdisciplinary and, therefore, highly cross-cutting. The economic dimension of the publishing process, and the history and culture of the book dominated the study subjects. There is also a growing trend of research on the impact of new technologies on the value chain and book distribution, without forgetting the increasing studies on new business models in the publishing industry.

Keywords: Publishing industry, Digital publishing, Book, Business models, Innovation, Value chain, Bibliometric analysis, Bibliometry

Introduction

Recently, there has been an increasing interest in the publishing industry as an area of research, reflected in the proliferation in the number of works globally published.

Indeed, the publishing industry actively boosts economic development in some countries. According to the latest report from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the revenue generated in 2020 in the publishing industry (commercial and educational sector) amounted to more than USD 64.4 billion.

The countries with the highest net income during 2020 for their publishing industry were: the United States with USD 23.6 billion and Japan with USD 10.8 billion, followed by Germany (USD 10.6 billion), the United Kingdom (USD 4.8 billion), Italy (USD 3.5 billion), France (USD 2.9 billion), Spain (USD 2.7 billion), Brazil (USD 1.0 billion) and Turkey (USD 0.9 billion).

The countries with the highest number of titles published during 2020 were: the United Kingdom (186,000), Italy (125,548), France (97,327), Turkey (88,975), Spain (83,622), Germany (77,272), Japan (69,850) and Brazil (46,083).

These global data show a whole scope of the publishing activity’s weight in the World and underlines the relevance of a sector facing significant changes in the last two decades of the twenty-first century (mainly new media, formats, and digital business models) and the new challenges for the third decade focused on an increasingly ‘transmedia’ and more transversal business context.

All these aspects have promoted a growing body of academic literature on the publishing industry that allows us to know from a scientific perspective the impact and evolution of diverse phenomena and factors shaping the publishing business roadmap in each country.

The general goal of this work is to carry out a bibliometric analysis of the scientific production in the publishing industry between 2012 and 2022. For this purpose, the following research posed the following questions:

1RQ. What are the leading academic publications that collect scientific production around the publishing industry? 2RQ. Who are the most productive and influential authors in research on the publishing industry? 3RQ. From which countries do the published academic works come? 4RQ. In which universities are research on the publishing industry concentrated?

This research used the information available in Scopus to address this bibliometric analysis.

The analysis conducted in this work is exploratory, descriptive, and quantitative, based on the techniques and tools of bibliometric analysis of the documents stored in the Scopus bibliographic database.

Literature Review

Research in any discipline or area of knowledge generates considerable scientific production. This activity results in numerous academic articles whose compilation and analysis are necessary to be able to advance in the different fields of research and where bibliometric studies acquire great importance and utility by making visible themes, authors, and scientific impact of the consulted works [ 1 , 2 ].

The bibliometric analysis of scientific publications constitutes a fundamental part of the research process tools, becoming an essential evaluation method [ 3 , 4 ]. The enormous utility of bibliometrics allows us to reflect on the studies carried out in a specific field of knowledge, know the people and institutions related to a concrete research area, and evaluate the performance of said people and institutions [ 5 ]. Bibliometric analysis studies and measures the quantity and quality of books, articles, and other forms of publications through mathematical and statistical methods [ 6 ], allowing to find not obvious patterns but helpful for the advancement of research and scientific development, as well as to understand the past and forecast the future of a thematic area of research [ 2 , 7 ].

Bibliometrics is the set of quantitative methods helpful for describing and measuring academic literature [ 8 , 9 ]. Bibliometric analysis starts from the idea that there is a strong and direct link between citations and the content of the cited articles [ 10 ].

Bibliometric studies mainly use quantitative analyzes of publications that pertain to a specific phenomenon [ 11 ]. It is an efficient procedure to understand how a field of research emerges and develops. Therefore, it is possible to measure the evolution of a concrete research area through its scientific production and its productivity over a specific period. Bibliometric analysis can examine the intellectual structure, areas of knowledge, geographic areas, research themes and methods, and maturity levels of the topics of a scientific discipline or journal [ 12 ].

The bibliometric analysis provides a more objective approach to exploring research trends and performance, acting as a complementary method to traditional literature reviews [ 13 ]. A possible classification of the bibliometric analyzes is the following [ 14 ]: (i) Studies on the ranking and assessment of scientific journals. (ii) studies on article identification, which covers the contributions of authors, institutions, and regions, (iii) content analysis, devoted to observing research trends, the growth of scientific production, topics covered, and methodologies applied; iv citation analysis, examining the influence of authors, articles, and journals, and v analysis of research carried out in specific countries.

Although there are many bibliometric studies on different thematic, geographic, and institutional areas, fewer focus on analyzing and characterizing the scientific production of the publishing sector. The general goal of this research is to reduce the lack of studies that address the bibliometric analysis of the research carried out in the last two decades around the publishing industry. For this purpose, this work used the third of the five categories mentioned above.

Methodology

This study presents the results obtained from a bibliometric analysis with a time-limited coverage between 2012 and 2021.

It is significant to assess which database to choose to measure academic production [ 15 ]. This research opted for the Scopus database as a source of bibliographic information since it offers access to different interdisciplinary databases, provides tools to manage it, and meets other criteria such as the number of citations and accessibility [ 16 ]. Elsevier Science introduced the Scopus database in 2004. It quickly became a good alternative as Scopus is currently the largest database of abstracts and citations of peer-reviewed literature containing active coverage of nearly 25,000 journals published by more than 5000 international publishers and covering periods, in many cases, since 1996 [ 17 ].

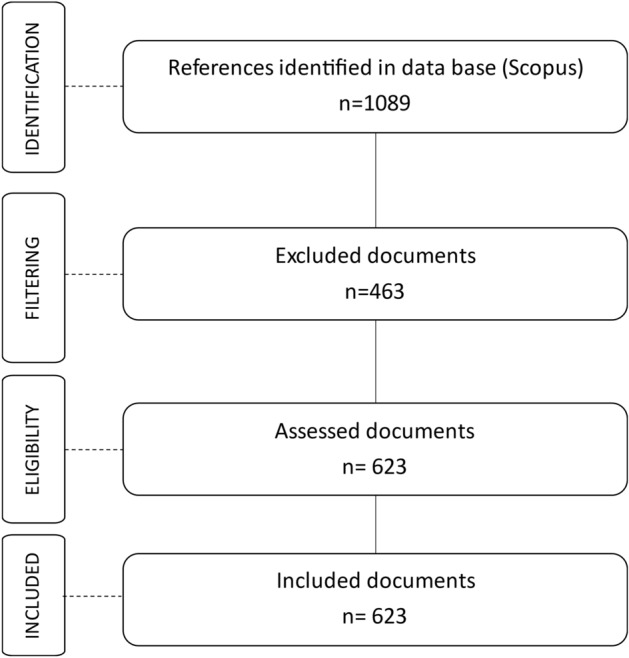

This work conducted two searches in June 2022 in the Scopus database to collect the analyzed documents. Figure 1 shows the methodological process followed in this research.

Process of search, recovery, and information selection for bibliometric analysis

(Source: own elaboration)

Results and Discussion

Analysis units and search period.

The data search procedure followed in this study identified 2130 related documents in Scopus, using the following search algorithm for the titles, abstracts, and keywords: ([“publishing sector”] OR [ “publishing industry*”]).

According to the proposed research, the researchers established a preliminary filter made by search period (2012–2021), which resulted in 1089 documents. Subsequently, based on the type of document obtained (Table 1 ), the researchers decided to use only the articles, which would give 623, which will be the documents used for the bibliometric analysis.

Analysis units

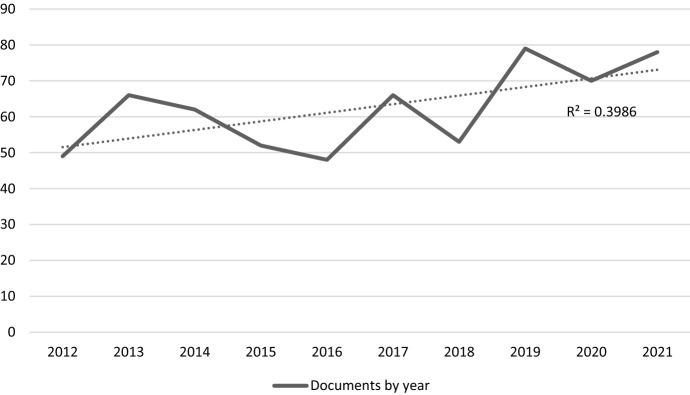

Figure 2 shows the number of scientific articles in the period (2012–2021), underlying that the most and less productive years were 2019 and 2016, respectively.

Quantification of yearly scientific publications

Figure 2 includes a trend line in the graph to assess the relevance of projecting the annual number of publications for the next decade using a simple linear regression, which shows a positive slope. However, the coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.3986, which indicates that it is not a result from which to infer a consistent future projection.

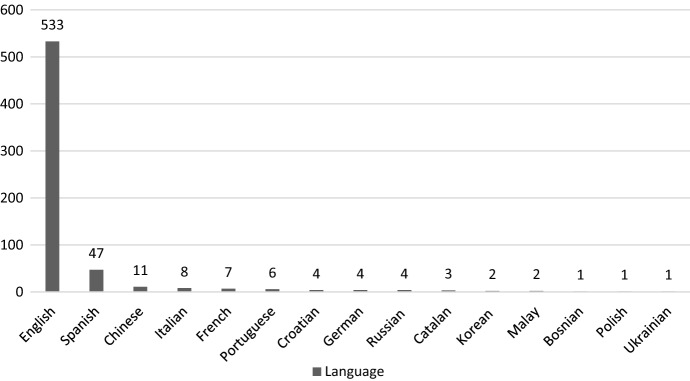

Language and Publishing Medium

One of the significant aspects of any line of research is the language since it significantly conditions its reaching and impact on the scientific community. In Scopus, 533 were published in English, 47 in Spanish, 11 in Chinese, 8 in Italian, 7 in French, 6 in Portuguese, 4 in Croatian, German, and Russian, respectively; 3 in Catalan, 2 in Korean, and Malay, respectively, and finally, 1 in Bosnian, Polish and Ukrainian, respectively (Fig. 3 ).

Publishing language

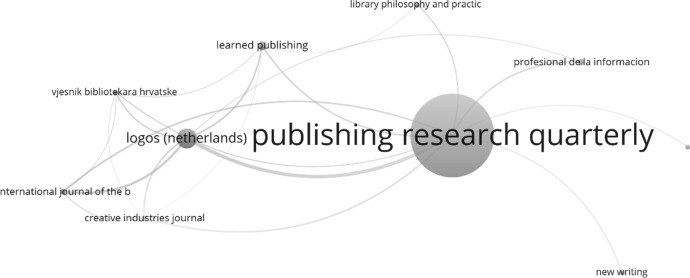

One of the determining aspects in any bibliometric study is the identification of the publishing media since it helps researchers identify journals for publishing purposes or for identifying studies on the research subject. The bibliometric analysis indicates that 160 academic journals have published at least one study on the publishing industry. Table 2 shows the ten academic journals that publish the most about it.

Top 20 publishing media

Fuente: Elaboración propia

In the results of the publishing media, it stands out that the first media corresponds to Publishing Research Quarterly: a peer-reviewed publication of original articles that offers significant research and analysis on the full range of the publishing industry. The journal examines the content development, production, distribution, and marketing of books, magazines, newspapers, and online information services in relation to the social, political, economic, and technological conditions that shape the publishing process. It is indexed in Scopus, WoS, Google Scholar, and Emerging Sources Citation Index, among others. Among the top twenty magazines, two written in Spanish stand out: Profesional de la Información and Revista General de Información y Documentación, which occupy 4th and 19th place, respectively.

Figure 4 shows the bibliometric map of the scientific production in the publishing industry according to the journals that have published five or more articles with at least one citation.

Bibliometric map by academic journals

In the green cluster appears the Publishing Research Quarterly, which occupies the first position for the number of articles and citations received. Besides, it is the academic journal where the most relevant articles on the subject were published.

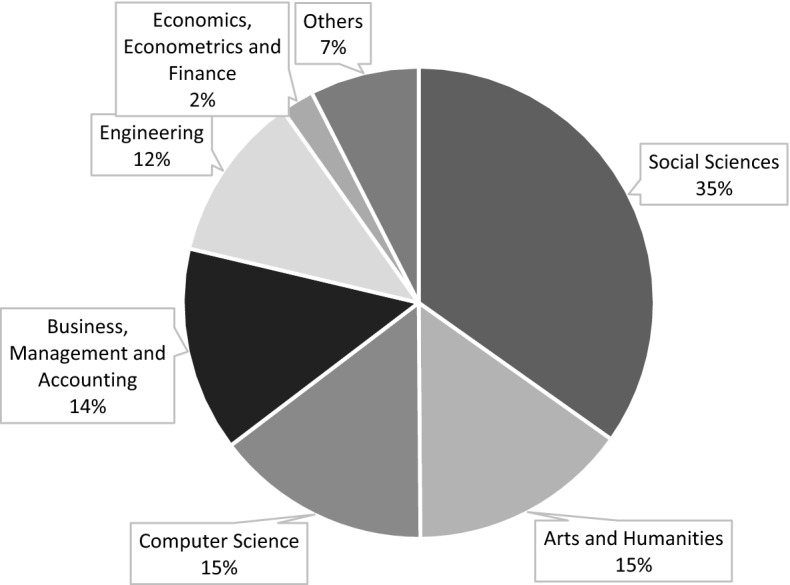

Serial titles may be in more than one area. Figure 5 shows the most relevant research areas.

Document by subject area

The fields of publishing industry studies are Social Sciences (35%), Arts and Humanities (15%), and Computer Sciences (15%). Many works find their starting point in the findings of Information and Computer Science, borrowing methods from Sociology, Cultural Studies, and Economics, without forgetting because of the last technological transformations, the Information and Communication Technologies studies.

Authors, Countries, and Institutions

This section analyzes three parameters: authors, countries, and organizations.

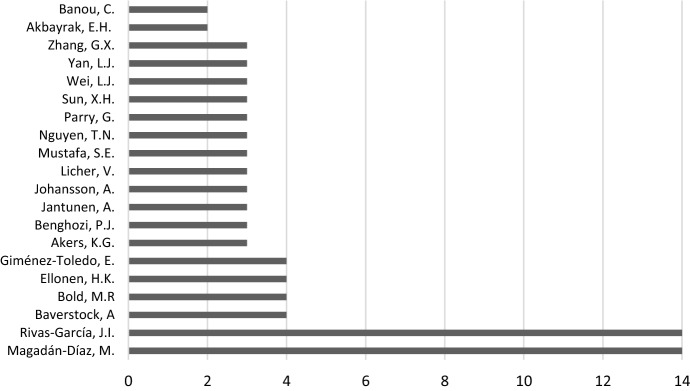

One of the determining aspects is to identify the authors with the highest scientific production on a subject. Their monitoring by other researchers allows for identifying and analyzing how a subject of study evolves. Figure 6 shows the most productive authors who have published at least three articles about the subject of study during the period analyzed.

The 20 most productive authors

The most productive authors are Marta Magadán-Díaz and Jesús I. Rivas-García, professors at the International University of La Rioja in Spain who store a maximum of 14 documents in Scopus.

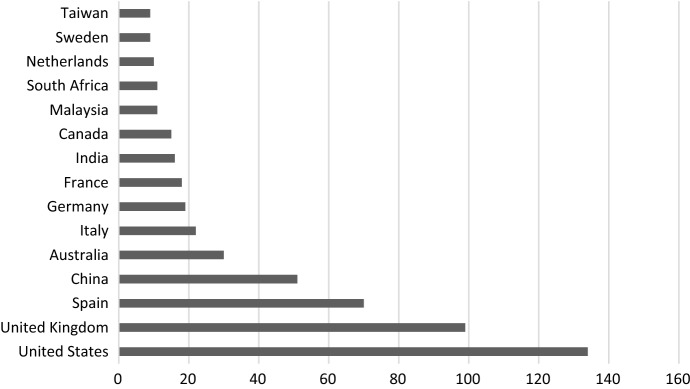

The results show that the United States is the first country by affiliation of its authors (125). In second place is the United Kingdom (100) and, in third place, Spain (62). Figure 7 shows the documents from the top 20 countries by affiliation of their authors.

Most productive countries according to the authors’ affiliation

On the other hand, Table 3 shows the top fifteen producing organizations (research centers, universities) with the highest representation in production in the publishing industry.

Production in the top 20 research centers and universities

Source: own elaboration

As can be seen in Table 3 , the following institutions stand out in the Spanish geographical area: “International University of La Rioja” with 15 documents, the University of Salamanca and the University of Granada with 6, the Complutense University with 5, and the University of Barcelona and the CSIC with 4.

Citations and Keywords

Table 4 shows the 20 most relevant articles in Scopus within the historical series, indicating the year of publication, the authors, and the journal.

Most relevant articles

As seen in Table 4 , 55% of the 20 most relevant articles in the Scopus database appear published in the Publishing Research Quarterly.

Table 5 shows the 20 most cited articles in the publishing industry research, ordered according to the number of citations. It also includes information on authors, specialized journals, year of publication, total citations, and the average number of citations per year for each article.

The top twenty more cited articles

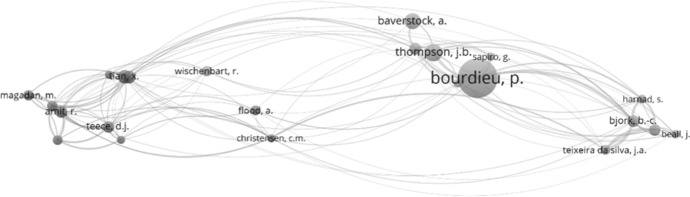

Another relevant indicator to analyze corresponds to the structure of the published documents. Figure 8 shows the influence of the existing network connections when analyzing the co-citations, for which authors with a minimum number of 20 citations were included.

Bibliometric map of the co-citations-articles relationship

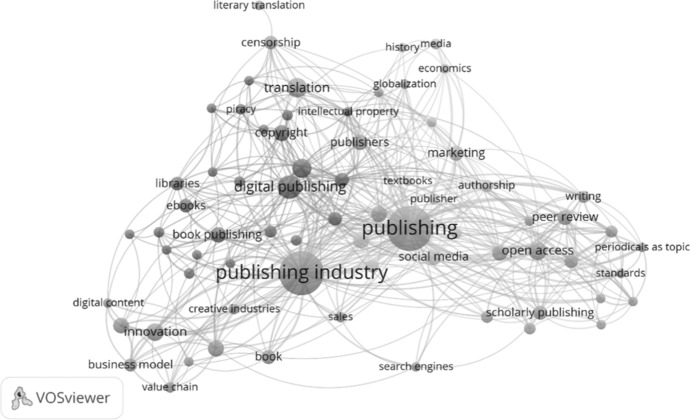

The research topics, according to the keywords of the articles, allow for analyzing the conceptual blocks addressed in the scientific production. Table 6 shows the six most recurrent keywords, and Fig. 9 presents the network map among keywords according to the frequency and keywords’ co-occurrence in the analyzed documents.

Frequency of keywords in scientific production in Scopus

Networks among keywords of the articles published on the publishing industry in Scopus

When analyzing the keywords, we observe that the terms ‘publishing’, ‘publishing industry’, and ‘digital publishing’ are among the most representative.

This analysis selected the 1000 keywords repeated in at least five different articles. Figure 9 shows that the network contains five clusters identified by a particular color (in order of importance): green, blue, red, purple, light blue, and yellow. Each one presents the most used concepts in research in the publishing industry, and the concept size is related to its absolute frequency.

Conclusions

The general goal of this study has been to review the scientific production of the publishing industry in the Scopus database.

Since 2012, production in the publishing industry has been gradually increasing. On the other hand, the majority language in which research is published in English, followed by Spanish.

The top four academic publications that collect scientific production around the publishing industry include Publishing Research Quarterly, Logos Netherlands, Learned Publishing, and Profesional de la Información.

The most productive and influential authors in research on the publishing industry are Marta Magadán-Díaz and Jesús I. Rivas-García, professors at the International University of La Rioja in Spain who contributed a maximum of 14 documents to Scopus in the period analyzed.

Regarding the countries with the highest scientific production on this subject, the United States stands out, followed by the United Kingdom and Spain. In relation to the geographical scope of influence, Europe stands out (the United Kingdom and Spain). The United Kingdom counts with the University College London as the most representative institution, followed the Oxford Brookes University and the University of Oxford. Spain appears represented by the International University of La Rioja, the University of Salamanca, and the University of Granada.

Finally, the analysis of the relational nodes of the keywords shows us that there are six main trends related to (a) digital publications (digital and electronic publishing, digitization, formats, platforms, applications, devices, digital developments, content management), (b) those linked to academic publishing and the development of open Access, (c) studies based on technological change, new business models and their effects on the value chain, as well as pricing strategies and distribution options based on book format and reader preferences, (d) those that refer to book marketing, (e) the use of social networks and the proliferation of self-publishing, and (f) everything related to intellectual property and the sale of rights. Many of these works borrow methods from the social sciences: sociology, social communication, and media studies, as well as studies of history, culture, and literary studies. The most used are the quantitative studies.

This article highlights that research on the global book publishing market is interdisciplinary and, therefore, highly cross-cutting. The economic dimension of the publishing process, and the history and culture of the book dominated the study subjects. There is also a growing trend of research on the impact of new technologies on the value chain and book distribution, without forgetting the increasing studies on new business models in the publishing industry.

This bibliometric analysis on the publishing industry presents a descriptive and analytical overview using Scopus: one of the databases with the highest impact on the scientific community. Therefore, it allows researchers, professionals in the field, and institutions to visualize the most developed trends and emerging lines of research to continue advancing in the study area.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marta Magadán-Díaz, Email: [email protected].

Jesús I. Rivas-García, Email: [email protected]

- 1. Delgado Á, Vázquez E, Belando MR, López EJ (2019) Análisis bibliométrico del impacto de la investigación educativa en diversidad funcional y competencia digital: web of Science y Scopus. Aula Abierta 48(2): 147–56. 10.17811/rifie.48.2.2019.147-156

- 2. Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. 2021;133:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Gómez R, Luna RM. Cuatro décadas de biblioteconomía y documentación en España: Análisis bibliométrico de producción científica. Revista Española de Documentación Científica. 2022;45(3):E334. doi: 10.3989/redc.2022.3.1878. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Khan MA, Pattnaik D, Ashraf R, Ali I, Kumar S, Donthu N. Value of special issues in the journal of business research: a bibliometric analysis. J Bus Res. 2021;125:295–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.015. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Palmatier RW, Houston MB, Hulland J. Review articles: purpose, process, and structure. J Acad Mark Sci. 2018;46(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11747-017-0563-4. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Snyder H. Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. 2019;104:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Ball R. Handbook bibliometrics. De Gruyter Saur. 2020 doi: 10.1515/9783110646610. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Ellegaard O. The application of bibliometric analysis: disciplinary and user aspects. Scientometrics. 2018;116(1):181–202. doi: 10.1007/s11192-018-2765-z. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Moral JA, Herrera E, Santisteban A, Cobo MJ. Software tools for conducting bibliometric analysis in science: an up-to-date review. Prof De La Inf. 2020;29(1):1–20. doi: 10.3145/epi.2020.ene.03. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Abramo G, D’Angelo C, Reale E. Peer review vs bibliometrics: which method better predicts the scholarly impact of publications? Scientometrics. 2019;121(1):537–554. doi: 10.1007/s11192-019-03184-y. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Liu H, Liu Y, Wang Y, Pan C. Hot topics and emerging trends in tourism forecasting research: a scientometric review. Tour Econ. 2019;25(3):448–468. doi: 10.1177/1354816618810564. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Guzeller CO, Celiker N. Bibliometrical analysis of Asia Pacific journal of tourism research. Asia Pac J Tour Res. 2019;24(1):108–120. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2018.1541182. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Choudhary RK, Awasthi S. Bibliometric visualisation tools. Library Prog (Int) 2018;38(2):319–324. doi: 10.5958/2320-317X.2018.00034.X. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Koseoglu MA, Sehitoglu Y, Parnell JA. A bibliometric analysis of scholarly work in leading tourism and hospitality journals: the case of Turkey. Anatolia. 2015;26(3):359–371. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2014.963631. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Norris M, Oppenheim C. Comparing alternatives to the Web of Science for coverage of the social sciences’ literature. J Informet. 2007;1(2):161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2006.12.001. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Okagbue HI, Teixeira da Silva JA. Correlation between the CiteScore and Journal Impact Factor of top-ranked library and information science journals. Scientometrics. 2020;124(1):797–801. doi: 10.1007/s11192-020-03457-x. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Zhu J, Liu W. A tale of two databases: the use of web of science and scopus in academic papers. Scientometrics. 2020;123(1):321–335. doi: 10.1007/s11192-020-03387-8. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (822.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The Oligopoly of Academic Publishers in the Digital Era

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations École de bibliothéconomie et des sciences de l’information, Université de Montréal, C.P. 6128, Succ. Centre-Ville, Montréal, QC. H3C 3J7, Canada, Observatoire des Sciences et des Technologies (OST), Centre Interuniversitaire de Recherche sur la Science et la Technologie (CIRST), Université du Québec à Montréal, CP 8888, Succ. Centre-Ville, Montréal, QC. H3C 3P8, Canada

Affiliation École de bibliothéconomie et des sciences de l’information, Université de Montréal, C.P. 6128, Succ. Centre-Ville, Montréal, QC. H3C 3J7, Canada

- Vincent Larivière,

- Stefanie Haustein,

- Philippe Mongeon

- Published: June 10, 2015

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502

- Reader Comments

The consolidation of the scientific publishing industry has been the topic of much debate within and outside the scientific community, especially in relation to major publishers’ high profit margins. However, the share of scientific output published in the journals of these major publishers, as well as its evolution over time and across various disciplines, has not yet been analyzed. This paper provides such analysis, based on 45 million documents indexed in the Web of Science over the period 1973-2013. It shows that in both natural and medical sciences (NMS) and social sciences and humanities (SSH), Reed-Elsevier, Wiley-Blackwell, Springer, and Taylor & Francis increased their share of the published output, especially since the advent of the digital era (mid-1990s). Combined, the top five most prolific publishers account for more than 50% of all papers published in 2013. Disciplines of the social sciences have the highest level of concentration (70% of papers from the top five publishers), while the humanities have remained relatively independent (20% from top five publishers). NMS disciplines are in between, mainly because of the strength of their scientific societies, such as the ACS in chemistry or APS in physics. The paper also examines the migration of journals between small and big publishing houses and explores the effect of publisher change on citation impact. It concludes with a discussion on the economics of scholarly publishing.

Citation: Larivière V, Haustein S, Mongeon P (2015) The Oligopoly of Academic Publishers in the Digital Era. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0127502. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502

Academic Editor: Wolfgang Glanzel, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, BELGIUM

Received: January 14, 2015; Accepted: March 24, 2015; Published: June 10, 2015

Copyright: © 2015 Larivière et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Data Availability: Aggregated data will be available on Figshare upon acceptance of the manuscript. However, restrictions apply to the availability of the bibliometric data, which is used under license from Thomson Reuters. Readers can contact Thomson Reuters at the following URL: http://thomsonreuters.com/en/products-services/scholarly-scientific-research/scholarly-search-and-discovery/web-of-science.html .

Funding: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors also acknowledge financial support from the Canada Research Chairs program.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

This year (2015) marks the 350 th anniversary of the creation of scientific journals. Indeed, it was in 1665 that the Journal des Sçavans and the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London were first published, in France and in England respectively. They were founded with the intent to advance scientific knowledge by building on colleagues’ results and avoid duplication of results, and established both the principles of scientific priority and peer review. They changed the process of scholarly communication fundamentally, from personal correspondence through letters (which had become “too much for one man to cope with in his daily reading and correspondence”) [ 1 ], society meetings, and books to a more structured and regular distribution of scientific advancements. This structured form, combined with a regular and wide dissemination, enabled systematic recording and archiving of scientific knowledge [ 1 – 4 ].

Since the 17 th century, the importance of journals for diffusing the results of scientific research has increased considerably. After coexisting alongside correspondence, monographs and treaties—which often took several years to be published—they became, at the beginning of the 19 th century, the fastest and most convenient way of disseminating new research results [ 5 – 7 ] and their number grew exponentially [ 1 , 8 ]. During the 20 th century they consolidated their position as the main media for diffusing research [ 6 ], especially in the natural and medical sciences [ 9 ]. Scholarly journals also contributed to the professionalization of scientific activities by delimiting the frontier between popular science and the research front and, as a consequence, increased the level of specialization of research and the formation of disciplines. Interestingly, while the majority of periodicals emerged from scientific societies, a significant proportion were published by commercial ventures as early as in the Victorian era. At that time, these commercial publishing houses proved more efficient in diffusing them than scientific societies [ 10 ]. However, prior to World War II, most scholarly journals were still published by scientific societies [ 11 ]. Data from the mid-1990s by Tenopir and King [ 12 ] suggests an increase of commercial publishers’ share of the output; by then, commercial publishers accounted for 40% of the journal output, while scientific/professional societies accounted for 25% and university presses and educational publishers for 16%. Along these lines, the UK Competition Commission measured various publishers’ shares of ISI-indexed papers for the 1994–1998 period and showed that, over this period, Elsevier accounted for 20% of all papers published [ 13 ]. One could expect, however, that these numbers have changed during the shift from print to electronic publishing. Indeed, many authors have discussed the various transformations of the scholarly communication landscape brought by the digital era (see, among others, Borgman [ 14 – 15 ]; Kling and Callahan [ 16 ]; Tenopir & King [ 17 ]; Odlyzko [ 18 ]). However, although the digital format improved access, searchability and navigation within and between journal articles, the form of the scholarly journal was not changed by the digital revolution [ 16 , 19 ]. The PDF became the established format of electronic journal articles, mimicking the print format [ 20 ]. What was affected by the digital revolution is the economic aspect of academic publishing and the journal market.

The literature from the late 1990s suggests that the digital era could have had two opposite effects on the publishing industry. As stated by Mackenzie Owen [ 21 ], while some authors saw the Web as a potential solution to the serials’ crisis—decreasing library budgets facing large and constant annual increases of journal subscription rates [ 22 , 23 ]—most authors hypothesized that it would actually make the situation worse [ 24 ] or, at least, not provide a solution [ 25 , 26 ]. Despite the fact that it is generally believed that the digitalization of knowledge diffusion has led to a higher concentration of scientific literature in the hands of a few major players, no study has analyzed the evolution over time of these major publishers’ share of the scientific output in the various disciplines. This paper aims at providing such analysis, based on all journals indexed in the Web of Science over the 1973–2013 period.

This paper uses Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science (WoS)—including the Science Citation Index Expanded, the Social Sciences Citation Index and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index—transformed into a relational database optimized for bibliometric analysis. On the whole, 44,483,425 documents are analyzed for the 1973–2013 period, which include all document types published by various journals. In addition to indexing authors’ names, addresses and cited references, which are the units of analysis typically used in bibliometric studies, the WoS indexes the name, city and country of the publisher of the journal for each issue. Using this information, which changes over time, we are thus able to assign journals and papers to a publisher and see the evolution of journal ownership. One limitation of this source of data is that it does not index all of the world’s scientific periodicals but only those indexed in the WoS, which meet certain quality criteria such as peer review and which are the most cited in their respective disciplines. Hence, this analysis is not based on the entire scientific publication ecosystem but, rather, on the subset of periodicals that are most cited and most visible internationally.

The journal publishing market is a complex and dynamic system, with journals changing publishing houses and publishing houses acquiring or merging with competitors. Although these changes should be reflected in the publisher information provided for each issue, in some cases, the name of the publisher does not change immediately after a merger or an acquisition. Publishers’ activities are often distributed among multiple companies under their control, and over the past 40 years, there have been many mergers and acquisitions involving entire companies or parts of them. We looked at the mergers and acquisitions history of major publishers, based on their number of papers published, in order to identify and associate the companies that came to be under their control, and conversely the companies which they eventually sold. These publishers are the American Chemical Society, American Institute of Physics, American Physical Society, Cambridge University Press, Emerald, IEEE, Institute of Physics, Karger, Nature Publishing Group, Optical Society of America, Oxford University Press, Reed-Elsevier, Royal Society of Chemistry, Sage Publications, Springer, Taylor & Francis, Thieme Publishing Group, Wiley-Blackwell, and Wolters Kluwer. For example, Reed-Elsevier bought Pergamon Press in 1991 but, in the WoS, journals remain associated with Pergamon Press until the year 2000. Hence, we assigned any journal published by Pergamon Press since 1991 to Reed-Elsevier. In the case of partial acquisitions, journals were assigned to the publisher only if at least 51% of the company was under its control. Historical merger and acquisition data up to 2006 was found in the report by Munroe [ 27 ]. The data for subsequent years was retrieved from the companies’ profiles in the Lexis Nexis database, as well as in the press releases found on publishers’ websites.

Fig 1A presents, for Natural and Medical Sciences (NMS) and Social Sciences and Humanities (NMS), the proportion of papers published by the top five publishers that account for the largest number of papers in 2013, as well as the proportion of papers published in journals others than those of the top five publishers. Fig 1B provide numbers for the proportion of journals published by various publishers, while Fig 1C presents the publishers’ share of citation received. What is striking for both domains is the drop, since the advent of the digital era in the in the mid-1990s, in the proportion of papers, journals and citations that are published/received by journals from publishers other than the five major publishers. In both NMS and SSH, Reed-Elsevier, Wiley-Blackwell, Springer, and Taylor & Francis are amongst the top five publishers with the highest number of scientific documents in 2013. While in NMS the American Chemical Society makes it to the top five (in fourth place in 2013), the fifth most prolific publisher in the SSH is Sage Publications. Hence, while all top publishers in SSH are private firms, one of the top publishers in NMS is a scientific society.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502.g001

In terms of numbers of papers published, the five major publishers in NMS, accounted, in 1973, for little more than 20% of all papers published. This share increased to 30% in 1996, and to 50% in 2006, the level at which it remained until 2013 when it increased again to 53%. In this domain, three publishers account for more than 47% of all papers in 2013: Reed-Elsevier (24.1%; 1.5 fold increase since 1990), Springer (11.9%; 2.9 fold increase), and Wiley-Blackwell (11.3%; 2.2 fold increase). The American Chemical Society (3.4%; 5% decrease) and Taylor & Francis (2.9%; 4.9 fold increase) only account for a small proportion of papers. In the SSH, the concentration increased even more dramatically. Between 1973 and 1990, the five most prolific publishers combined accounted for less than 10% of the published output of the domain, with their share slightly increasing over the period. By the mid-1990s, their share grew to collectively account for 15% of papers. However, since then, this share has increased to more than 51%, meaning that, in 2013, the majority of SSH papers are published by journals that belong to five commercial publishers. Specifically, in 2013, Elsevier accounts for 16.4% of all SSH papers (4.4 fold increase since 1990), Taylor & Francis for 12.4% (16 fold increase), Wiley-Blackwell for 12.1% (3.8 fold increase), Springer for 7.1% (21.3 fold increase), and Sage Publications for 6.4% (4 fold increase). On the whole, for these two broad domains of scholarly knowledge, five publishers account for more than half of today’s published journal output. Very similar trends are observed for journals and citations, although with a less pronounced concentration, especially for citations in NMS which have remained quite stable between 1973 and the late 1990s. For instance, while the top 5 publishers account for 53% (NMS) and 51% (SSH) of papers, their proportion of journals is of 53% (NMS) and 54% (SSH), and of 55% (NMS) and 54% (SSH) when it comes to citations received. This suggests that the top 5 publishers publish a higher number of papers per journal than other publishers not making the top five, and that their papers obtain, on average, a lower scientific impact.

The increase in the top publishers’ share of scientific output has two main causes: 1) the creation of new journals and 2) existing journals being acquired by these publishers. Fig 2 presents, for both NMS and SSH, the number of journals over time that changed ownership from small to big publishers—that is, the four publishers with the largest share of published papers in both NMS and SSH—and, for NMS, the number of journals that moved from big to small publishing houses. Since we intend to emphasize developments of the publishing market by publisher type and not single actors, changes among small as well as among big publishers are not shown. It can be seen in both domains that, before 1997, publisher type changes were overall quite rare and the majority consisted of changes from big to small publishers in NMS. Importantly, not a single journal was found to have switched from a big to small publisher in SSH during the entire period of analysis. A first important large wave of journal acquisitions by the big publishers occurred in 1997–1998, when Taylor & Francis acquired several journals from Gordon & Breach Science Publishers, Harwood Academic Publishers, Scandinavian University Press, Carfax Publishing and Routledge. In the same period Reed-Elsevier acquired a few small publishers like Butterworth-Heinemann, Ablex Publications, JAI press, Gauthier-Villars and Expansion Scientifique Française. The next important peak occurred in 2001, and is mainly due to Reed-Elsevier continuing a series of acquisitions, including Academic Press, Churchill Livingstone, Mosby and WB Saunders. Finally, the peak of 2004 is mainly due to the acquisition of Kluwer Academic Publishers by Springer, who had not previously been involved in substantial journal acquisition activities. Wiley-Blackwell’s contribution to the four peaks in Fig 2 was steadier, with the company acquiring an average of 39 journals annually from various publishers during the 2001–2004 period.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502.g002

The share of journal papers published by the five publishers differs amongst the various disciplines in NMS and SSH. Figs 3 and 4 present the evolution of the top five publishers’ share of papers by discipline. Not surprisingly, chemistry has the highest level of concentration, as one of its disciplinary publishers, the ACS, made it to the top five most prolific publishers of NMS. For most disciplines, however, concentration in the top five publishers increased from between 10% and 20% in 1973 to between 42% and 57% in 2013, with a clear change of slope in the mid-1990s. Physics, on the other hand, follows a different pattern: after increasing from 20% in 1973 to 35% in 2000, it has since then remained stable and is subsequently the discipline where the top five publishers account for the lowest proportion of papers published. This lower concentration of papers in big publishers’ journals is mainly due to the strength and size of physics’ scientific societies, whose journals publish an important proportion of scientific papers in the field ( Fig 5 ). In 2013 for instance, journals of the American Physical Society (APS) and of the American Institute of Physics (AIP) each account for 15% of papers, while those of the Institute of Physics (IOP) represent 8% of papers. It is also worth noting that, in physics, Reed-Elsevier’s journals’ share of papers also decreased over the last decade or so, from 28% of papers in 2001 to 21% in 2013. Springer, however, increased its percentage of physics papers from 3% to 11% over the same period. On the whole, the central importance of scientific societies in physics, the presence of arXiv, the central preprint server of physics, astrophysics and mathematics, as well as Open Access agreements such as SCOAP3 ( http://scoap3.org/ ), are likely to make the field less profitable and thus less interesting for commercial publishers. In biomedical research, the share of the top five publishers almost reached 50% in 2009 (49%), but then decreased to 42% in 2013, mainly as a result of the emergence of new publishers, such as the Public Library of Science and its mega-journal PLOS ONE, which publishes more than 30,000 papers per year.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502.g003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502.g004

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502.g005

Fig 4 clearly shows that disciplines typically labelled as ‘social sciences’ behave differently from the arts and humanities. For each discipline within the domain of social sciences (psychology, professional fields, social sciences and social aspects of health), there is an unambiguous change in the slope in the mid-1990s: while the top five—in this case, commercial—publishers accounted for percentages between 15% and 22% of the output in 1995, these percentages increased to between 54% and 71% in 2013. The disciplines in social sciences, which includes specialties such as sociology, economics, anthropology, political sciences and urban studies, is quite striking: while the top five publishers accounted for 15% of papers in 1995, this value reached 66% in 2013. Combined, the top three commercial publishers alone—Reed-Elsevier, Taylor & Francis and Wiley-Blackwell—represent almost 50% of all papers in 2013. Psychology follows a similar pattern, with the top five publishers increasing from 17% in 1995 to 71% in 2013.

On the other hand, papers in arts and humanities are still largely dispersed amongst many smaller publishers, with the top five commercial publishers only accounting for 20% of humanities papers and 10% of arts papers in 2013, despite a small increase since the second half of the 1990s. The relatively low cost of journals in those disciplines—a consequence of their lower publication density—might explain the lower share of the major commercial publishers. Also, the transition from print to electronic—a strong argument for journals to convert to commercial publishers—has happened at a much slower pace in those disciplines as the use for recent scientific information is less pressing [ 28 ]. Moreover, these disciplines make a much more important use of books [ 9 ] and generally rely on local journals [ 29 ], all of which are factors that make it much less interesting for big publishers to buy journals or found new ones in the arts and humanities.

Fig 6 presents the changes in articles’ relative citation rates for journals that have changed from small to big and big to small publishers (see Fig 1 ) for the 10 years before and after the transition. We focus on two four-year periods to ensure comparable environments for the publishing market and selected 1995–1998 and 2001–2004, as they were identified as important consolidation phases in Fig 1 . More specifically, for NMS, those that have changed from small to big publishers increased their impact slightly following the change. However, while for the 2001–2004 cohort of journals this followed a drop in impact, impact of the 1995–1998 cohort was relatively stable before. For the journals moving from big to small publishers, there is no effect: impact remains similar prior to and after the change. In SSH, no noticeable effect can be observed: changing from a small to a big commercial publisher does not affect papers' citation rates. It is also worth mentioning that, except for journals moving from small to big publishers between 2001 and 2004, the mean impact of papers before and after remained below the world average. It suggests that, on average, journals changing publishers did not produce many high impact papers.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502.g006

Discussion and Conclusion

The effect of scientific societies.

“University presses and disciplinary associations were founded to disseminate research in the original cycle of scholarly communication. The faculty produced the work to be published; non-profit publishers organized the distribution of knowledge; the university library bought the published work at an artificially high price, as a subsidy for learned societies; and the faculty used this literature as the foundation for further research and teaching. […] However, over the past fifty years, as federal research funding has encouraged specialization, journal publishing has become commercialized, and some parts of the scientific and technical literature are now being monopolized by multinational publishing conglomerates.” (p. 89)

The economics of scholarly publishing

As one might expect, the consolidation of the publishing industry led to an increase of the profits of publishers. Fig 7 presents, as an example, the evolution of Reed-Elsevier’s profits over the 1991–2013 period, for the firm taken as a whole as well as for its Scientific, Technical & Medical division. One can clearly see in Fig 7A that, between 1991 and 1997, both the profits and the profit margin increased steadily for the company as a whole. While profits more than doubled over that period—from 665M USD to 1,451M USD—profit margin also rose from 17% to 26%. Profit margins decreased, however, between 1998 and 2003, although profits remained relatively stable. Absolute profits as well as the profit margin then rose again, with the exception of the 2008–2009 period of economic crisis, resulting in profits reaching an all-time high of more than 2 billion USD in 2012 and 2013. The profit margin of the company’s Scientific, Technical & Medical division is even higher ( Fig 7B ). Moreover, its profits increased by a factor of almost 6 throughout the period, and never dropped below 30% from one year to another. The profit margin of this division never decreased below 30% during the period observed, and steadily increased from 30.6% to 38.9% between 2006 and 2013. Similarly high profit margins were obtained in 2012 by Springer Science+Business Media (35.0%, see: http://static.springer.com/sgw/documents/1412702/application/pdf/Annual_Report_2012_01.pdf ), and in 2013 and John Wiley & Sons’ Scientific, Technical, Medical and Scholarly division (28.3%, see: http://www.wiley.com/legacy/about/corpnews/fy13_10kFINAL.pdf ) and Taylor and Francis (35.7%, see: http://www.informa.com/Documents/Investor%20Relations/Annual%20Report%202013/Informa%20plc%20Annual%20Report%20Accounts%202013.pdf ), putting them on a comparable level with Pfizer (42%), the Industrial & Commercial Bank of China (29%) and far above Hyundai Motors (10%), which comprise the most profitable drug, bank and auto companies among the top 10 biggest companies respectively, according to Forbes’ Global 2000 [ 30 ]. At a total revenue of 9.4 billion US dollars in 2011 [ 31 ], the majority of which were generated by a few publishing houses, the scientific journal publishing market faces oligopolistic conditions, where big players such as Elsevier, Springer, Taylor & Francis, Wiley-Blackwell and Wolters Kluwer determine annually increasing subscription rates that make up a considerable amount of research spending, leaving academic libraries with no other choice but to cancel subscriptions [ 20 , 32 , 33 ].

Compilation by the authors based on the annual reports of Reed-Elsevier. ( http://www.reedelsevier.com/investorcentre/pages/home.aspx ) Numbers for the Scientific, Technical & Medical division were only available in GBP; conversion to USD was performed using historical conversion rates from http://www.oanda.com .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502.g007

The possibility to increase profits in such an extreme fashion lies in the peculiarity of the economics of scholarly publishing. Unlike usual suppliers, authors provide their goods without financial compensation and consumers (i.e. readers) are isolated from the purchase. Because purchase and use are not directly linked, price fluctuations do not influence demand. Academic libraries, contributing 68% to 75% of journal publishing revenues [ 31 ], are atypical buyers because their purchases are mainly controlled by budgets. Regardless of their information needs, they have to manage with less as prices increase. Due to the publisher’s oligopoly, libraries are more or less helpless, for in scholarly publishing each product represents a unique value and cannot be replaced [ 19 , 20 , 33 , 34 ].

Scholarly publications themselves can be considered information goods with high fixed and low variable costs [ 35 , 36 ]. Regarding academic journals, fixed or first-copy costs comprise manuscript preparation, selection and reviewing as well as copy-editing and layout, writing of editorials, marketing, and salaries and rent, the two most substantial of which, manuscript writing and reviewing, are provided free of charge by the scholarly community [ 20 ]. In that sense and contrary to any other business, academic journals are an atypical information good, because publishers neither pay the provider of the primary good—authors of scholarly papers—nor for the quality control—peer review. On the publisher’s side, average first-copy costs of journal papers are estimated to range between 20 and 40 US dollars per page, depending on rejection rates [ 37 ]; [ 17 ], which neither explains open access publication fees as high as 5,000 $US (e.g., Cell Reports by Elsevier) nor hybrid journals, where publishers charge twice per article, i.e. the subscription and open access fees (e.g., Open Choice by Springer or Online Open by Sage Publications).

In addition, the Ingelfinger law, initiated by the publisher of the New England Journal of Medicine in 1969, prohibits authors from submitting their manuscript to more than one journal [ 38 ]. Although the law was initially created to protect the journal’s revenue streams and has become largely obsolete through electronic publishing [ 39 ], it is still a universal rule in academic journal publishing, often enforced by copyright transfer agreements. Hence, each journal has the monopoly on the scientific content of papers it publishes: paper A published in journal Y is not an alternative to paper B published in journal Z [ 11 ]. In other words, access to paper A does not replace access to paper B, both papers being complementary to each other.

Variable costs of academic journals are paid by the publisher and, as long as journals were printed and distributed physically, these costs were sizeable. In the print era, publishers had to typeset the manuscripts, print copies of journals, and send them to various subscribers. Hence, each time an issue was printed, sent and sold, another copy had to be printed to be sent and sold. However, with the advent of electronic publishing, these costs became marginal. The digital era exacerbated this trend and increased the potential revenues of publishers. While, in economic terms, printed journals can be considered as rival goods—goods that cannot be owned simultaneously by two individuals—online journals are non-rival goods [ 40 ]: a single journal issue that has been uploaded by the publisher on the journal’s website can be accessed by many researchers from many universities at the same time. The publisher does not have to upload or produce an additional copy each time a paper is accessed on the server as it can be duplicated ad infinitum , which in turn reduces the marginal cost of additional subscriptions to 0. In a system where the marginal cost of goods reaches 0, their cost becomes arbitrary and depends merely on how badly they are needed, as well as by the purchasing power of those who need them. In addition, costs are strongly influenced by the power relations between the buyer and seller, i.e. publishers and academic libraries. In such a system, any price is good for the seller, as the additional unit sold is pure profit. All these factors explain the different and often irrational big deals made between publishers and subscribers, with university libraries subscribing to a publisher’s entire set or large bundle of journals regardless of their specific needs [ 41 ]. Through these big deals, university researchers have been accustomed to, for almost 20 years, having access to an increasingly large proportion of the scientific literature published, which makes it very difficult for university libraries today to cancel subscriptions and negotiate out of big deals with publishers to optimize their collections and meet budget restrictions.

General conclusions

Since the creation of scientific journals 350 years ago, large commercial publishing houses have increased their control of the science system. The proportion of the scientific output published in journals under their ownership has risen steadily over the past 40 years, and even more so since the advent of the digital era. The value added, however, has not followed a similar trend. While one could argue that their role of typesetting, printing, and diffusion were central in the print world [ 20 , 7 ], the ease with which these function can be fulfilled—or are no longer necessary—in the electronic world makes one wonder: what do we need publishers for? What is it that they provide that is so essential to the scientific community that we collectively agree to devote an increasingly large proportion of our universities budgets to them? Of course, most journals rely on publishers’ systems to handle and review the manuscripts; however, while these systems facilitate the process, it is the researchers as part of the scientific community who perform peer review. Hence, this essential step of quality control is not a value added by the publishers but by the scientific community itself.

Thus, it is up to the scientific community to change the system in a similar fashion and in parallel to the open access and open science movements. And, indeed, the scientific community has started to react to and protest against the exploitative behaviour of the major for-profit publishers. In 2012, the “Cost of Knowledge” ( http://thecostofknowledge.com/ ) campaign started by Cambridge mathematician and Fields Medalist Timothy Gowers asked researchers to protest against Elsevier’s business model through a boycott against its journals by ceasing to submit to, edit and referee them. Started by a blogpost, the boycott was later termed the beginning of an “Academic Spring” [ 42 , 43 ]. Several university libraries, including large and renowned universities such as the University of California [ 44 ] and Harvard [ 45 ], stopped negotiations and threatened to boycott major for-profit publishers, while other universities—such as the University of Konstanz—simply cancelled all Elsevier subscriptions as they were neither able nor willing to keep up with their aggressive pricing policy: 30% increase over five years [ 46 , 47 ].

But these are exceptions. Unfortunately, researchers are still dependent on one essentially symbolic function of publishers, which is to allocate academic capital, thereby explaining why the scientific community is so dependent on ‘The Most Profitable Obsolete Technology in History’ [ 48 ]. Young researchers need to publish in prestigious journals to gain tenure, while older researchers need to do the same in order to keep their grants, and, in this environment, publishing in a high impact Elsevier or Springer journal is what ‘counts’. In this general context, the negative effect of various bibliometric indicators in the evaluation of individual researchers cannot be understated. The counting of papers indexed by large-scale bibliometric databases—which mainly cover journals published by commercial publishers, as we have seen in this paper—creates a strong incentive for researchers to publish in these journals, and thus reinforces the control of commercial publishers on the scientific community.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sam Work for proofreading and editing the manuscript, as well as the two referees, for comments and suggestions.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: VL. Performed the experiments: VL SH PM. Analyzed the data: VL SH PM. Wrote the paper: VL SH PM.

- 1. de Solla Price DJ. Little Science, Big Science. New York: Columbia University Press; 1963.

- 2. Haustein S. Multidimensional journal evaluation. Analyzing scientific periodicals beyond the impact factor. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Saur; 2012.

- 3. Tenopir C, King DW. (2009). The growth of journals publishing. In Cope B, Phillips A, editors. The Future of the Academic Journal. Oxford: Chandos Publishing; 2009. pp. 105–123.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 5. Harmon JE, Gross AG. The Scientific Literature: A Guided Tour. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 2007.

- 6. Meadows AJ. The Scientific Journal. London: Aslib; 1979.

- 7. Meadows AJ. Access to the results of scientific research: developments in Victorian Britain. In Meadows AJ, editor. Development of Science Publishing in Europe. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishing; 1980. pp. 43–62.

- 8. Meadows AJ. Communication in Science. Butterworths: Seven Oaks; 1974.

- 10. Brock WH. (1980). The Development of Commercial Science Journals in Victorian Britain. In Meadows AJ, editor. Development of Science Publishing in Europe, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1980. pp. 95–122.

- 11. Kaufman P. (1998). Structure and crisis: Markets and market segmentation in scholarly publishing. In: Hawkins BL, Battin P, editors. The Mirage of Continuity: Reconfiguring Academic Information Resources for the 21st Century. Washington D.C.: CLIR and AAU; 1998. pp. 178–192.

- 13. Office of Fair Trading. The market for scientific, technical and medical journals. A statement by the OFT. Report OFT396; 2002. Available: http://www.econ.ucsb.edu/~tedb/Journals/oft396.pdf . Accessed on: 2015 January 5.

- 14. Borgman CL. From Gutenberg to the global information infrastructure: Access to information in the networked world. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 2000.

- 15. Borgman CL. Scholarship in the Digital Age: Information, Infrastructure, and the Internet. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 2007.

- 17. Tenopir C, King DW. Towards Electronic Journals: Realities for Scientists, Librarians, and Publishers. Washington, D. C.: Special Libraries Association; 2000.

- 19. Keller A. Elektronische Zeitschriften. Grundlagen und Perspektiven. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag; 2005.

- 20. Mierzejewska BI. The Eco-system of Academic Journals. Doctoral dissertation, University of St. Gallen, Graduate School of Business Administration, Economics, Law and Social Sciences. Bamberg: Difo-Druck; 2008.

- 21. Mackenzie Owen J. The scientific article in the age of digitization. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. 22.

- 25. Lyman P, Chodorow S. (1998) The Future of Scholarly Communication. In Hawkins BL, Battin P, editors. The Mirage of Continuity: Reconfiguring Academic Information Resources for the 21st Century. Washington D.C.: CLIR and AAU; 1998. pp. 87–104.

- 27. Munroe, M.H. (2007). The academic publishing industry: a story of merger and acquisition. Available: http://www.ulib.niu.edu/publishers/

- 30. Chen L. Best of the biggest: How profitable are the world’s largest companies? Forbes. 13 May 2014. Available: http://www.forbes.com/sites/liyanchen/2014/05/13/best-of-the-biggest-how-profitable-are-the-worlds-largest-companies/ . Accessed 2015 January 5.

- 31. Ware M, Mabe M. The STM report. An overview of scientific and scholarly journal publishing. The Hague: International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers; 2012. Available: http://www.stm-assoc.org/2012_12_11_STM_Report_2012.pdf .

- 32. Cope B, Kalantzis M. Signs of epistemic disruption: transformations in the knowledge system of the academic journal. In B Cope, A Phillips, editors. The Future of the Academic Journal. Oxford: Chandos Publishing; 2009. pp. 11–61.

- 34. Meier M. Returning Science to the Scientists. Der Umbruch im STM-Zeitschriftenmarkt unter Einfluss des Electronic Publishing. München: Peniopel 2002.

- 35. Shapiro C, Varian HR. Information Rules. A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1998.

- 36. Linde F, Stock WG. Information Markets. A Strategic Guideline for the I-Commerce. Berlin / New York: De Gruyter Saur; 2011.

- PubMed/NCBI

- 40. Weimer DL, Vining AR. Policy Analysis: Concepts and Practice. Pearson: Prentice Hall; 2011.

- 42. Cook G. Why scientists are boycotting a publisher. The Boston Globe. 12 February 2012. Available: http://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2012/02/12/why-scientists-are-boycotting-publisher/9sCpDEP7BkkX1INfakn3NL/story.html . Accessed 2015 January 5.

- 43. Jha A. Academic spring: how an angry maths blog sparked a scientific revolution. The Guardian. 9 April 2012. Available: http://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/apr/09/frustrated-blogpost-boycott-scientific-journals . Accessed 2015 January 5.

- 44. Howard J. U. of California tries just saying no to rising journal costs. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 8 June 2010. Available: http://chronicle.com/article/U-of-California-Tries-Just/65823/ . Accessed 2015 January 5.

- 45. Sample I. Harvard University says it can’t afford journal publishers’ prices. The Guardian. 24 April 2012. Available: http://www.theguardian.com/science/2012/apr/24/harvard-university-journal-publishers-prices . Accessed 2015 January 5.

- 46. University of Konstanz. More expensive than science allows. Press release No. 28 of 26 March 2014. Available: http://www.aktuelles.uni-konstanz.de/en/presseinformationen/2014/28/ . Accessed 2015 January 5.

- 47. Vogel G. German University tells Elsevier ‘no deal’. Science Insider. 27 March 2014. Available: http://news.sciencemag.org/people-events/2014/03/german-university-tells-elsevier-no-deal . Accessed 2015 January 5.

- 48. Schmitt J. Academic journals: The most profitable obsolete technology in history. The Huffington Post Blog. 23 December 2014. Available: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jason-schmitt/academic-journals-the-mos_1_b_6368204.html . Accessed 2015 January 5.

Advertisement

Publishing Distribution Practices: New Insights About Eco-Friendly Publishing, Sustainable Printing and Returns, and Cost-Effective Delivery in the U.S.

- Published: 05 May 2022

- Volume 38 , pages 364–381, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Rachel Done 1 ,

- Rylee Warner 1 &

- Rachel Noorda 1

5445 Accesses

3 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated and highlighted the problems and opportunities within the book publishing industry’s distribution practices. This is a summary of the Publishing Distribution Practices report, researched and produced in collaboration with Portland State University, Independent Book Publishers Association, and PubWest. This article addresses research and recommendations for becoming carbon neutral, delivering books cost effectively, utilizing print-on-demand, minimizing returns, and examining supply chain issues raised by the pandemic. Findings include starting with paper and emissions assessment for more eco-friendly publishing; emphasizing pre-orders, local and discounted delivery, trade organization membership, and POS systems for cost-effective delivery; limiting outsourcing to restrict supply chain disruptions; reducing print runs and promoting books more effectively to minimize returns; and utilizing print-on-demand for proof copies and gap runs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reinvention, revolution and revitalization: real life tales from publishing’s front lines.

From the Gutenberg Galaxy to the Digital Clouds

‘predatory’ open access: a longitudinal study of article volumes and market characteristics.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA) and PubWest partnered with Portland State University’s Graduate Program in Book Publishing to conduct and analyze qualitative research to help the book industry improve distribution practices.

There are several industry problems that were identified as creating barriers and difficulty for good distribution practices in publishing. These problems include the following:

Offset printing is designed to support over-ordering because of economies of scale, so authors and publishers print more than they need to take advantage of lower per unit costs.

Print-on-demand is expensive and getting more expensive.

The quality of print-on-demand for four-color is not good.

Some offset printers can do digital runs, but the publishers have to have a warehousing solution to take advantage of them.

Publishers intentionally flood the market with excessive quantities of their lead titles (with big marketing campaigns) to make a show for said lead titles. Bookstores have nothing to lose by taking these buys because of the industry returns policy.

The publishing industry remains largely entrenched in a traditional trade distribution model despite significant changes in consumer purchasing habits and increased technology capabilities for electronic order management.

The global pandemic accelerated existing, growing supply chain challenges that include the closing and repurposing of paper mills, labor shortages in the graying field of print manufacturing, distributor consolidation, and the exponentially rising costs of materials and transportation.

Based on these industry problems, the executive directors of IBPA and PubWest, along with the IBPA sustainability working group, created research questions for the PSU students to investigate, under the supervision of Dr. Rachel Noorda.

What needs to be done to make book printing truly carbon neutral by 2050?

As consumer buying habits further migrate from retail to online, what does efficient and cost-effective delivery of print books to readers look like going forward?

Although COVID-19 did not create the book industry’s supply chain problems, it certainly exacerbated them. What chinks in the book industry’s armor were most exposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic?

What's stopping the industry from embracing POD as the preferred means for printing non-illustrated, black-and-white trade books?

How can the book industry decrease the returns rate for books sold into trade channels from an average of 30% to an average of 15% (or less)?

Five groups of graduate book publishing students investigated these research questions through a mixture of secondary research, interviews, and survey data. Their findings are particularly relevant to small- to medium-sized publishers but are also important for independent bookstores.

Becoming Carbon Neutral

What needs to be done to make book printing truly carbon neutral by 2050? Carbon neutrality (CN) indicates that there is net-zero release of CO 2 in the atmosphere. In practice, this means that no fossil fuels were used, the manufacturing did not interfere with natural systems for processing carbon, and no greenhouse gasses were released into the atmosphere during production [ 1 ]. In the U.S., there is currently no way to produce truly carbon neutral paper products. But that does not mean publishers can’t aim for producing low carbon products now, with the goal of CN in the long term. To analyze this, CN has been broken down into two parts: materials and capital/labor.

The material prices, manufacturing, handling, and distribution are primarily handled by mills, paper brokers, and printing presses [ 2 , 3 ]. For CN to be achieved, one needs to know the following:

Print & Plant, and Pulping

This is a common method by publishers where a new tree is planted for every one that is cut down, as seen in Fig. 1 . While this solution does help limit emissions, it is not enough in the long-term due to a variety of factors. One such factor is that only 50% of trees that are cut down actually get turned into paper; most are used as fuel for pulping. Pulping describes two processes: pulping timber to make paper and destroying books that have already been bound. Theoretically, the latter could be used to make more books, but the pulp from already bound books is typically not reusable to make PCW paper due to the glue and ink used, as well as the infrastructure capabilities of the press.

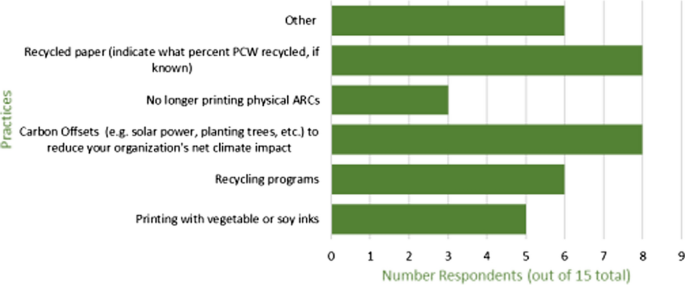

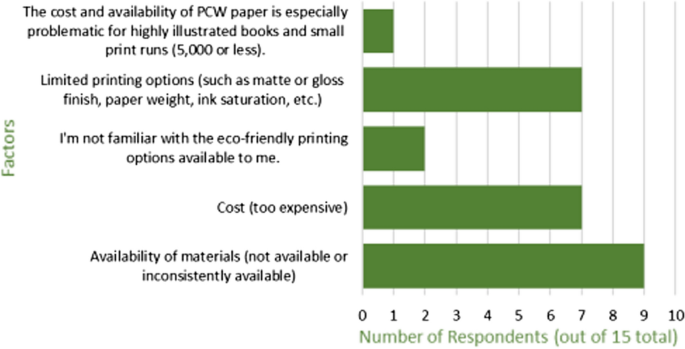

Currently used eco-friendly printing practices reported

Virgin Paper, and Post Consumer Waste (PCW) Paper

Virgin Paper (VP) is paper that has never been used before, while PCW is made out of recycled paper. Producing VP requires four times the amount of CO 2 per ton and uses enough energy to run an average U.S. home for 2 months, when compared to 100% PCW paper [ 4 ]. This is the main area where change can be made, and waste can be reduced by using as much PCW as possible [ 5 , 6 ].

Waste Run Off/Emissions and Energy

Currently, paper production is the third highest industry in the consumption of fossil fuels [ 7 ], and second largest emitter of greenhouse gasses. The industry is also one the largest pollutants for the environment, producing large amounts of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, mercury, and other carcinogens. Other than the use of harvesting and using paper, this is the factor that has the biggest ecological impact [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ].

Capital in this paper is defined as the monetary return on investment for publishers to shift to CN printing options, which are considered expensive currently by most small to midsize publishers. One of our respondents in our survey stated that "the cost and availability of PCW paper is especially problematic for highly illustrated books and small print runs (5000 or less)." And more expressed that the cost and availability of materials was their main barrier in achieving CN, as seen in Figs. 2 and 3 . In short, without an increased demand from the publishers for printers to use PCW paper, it will continue to be expensive and hard to find. If imprints of the Big Four used PCW paper, prices would eventually drop. Some, like Macmillan, are already doing so. It might also be pertinent to increase investments into legislation to build infrastructure to process waste effectively, due to paper being the single largest component of landfills in the U.S. [ 12 , 13 ].

Factors impeding implementation of more eco-friendly printing practices

Factors limiting ability to make books out of 100% recyclable materials

Labor includes those working in the printing industry, those working for the publishers, and even the machines and tools used to print. Labor has a significant impact on CN due to the consumption of materials. Changing editing and production methods would minimize the carbon impact of labor. Examples include, using PDF files for manuscripts, and advanced reader copies. The “print first, sell later” production model also needs to be retired. This model often creates a surplus that needs to be stored, transported, or even pulped later on. Encouragingly, we saw some publishers already starting to do this in our survey when asked on how they are reducing their pulping numbers, which can be seen in Tables 1 and 2 .

Due to the lack of investment in eco-friendly infrastructure by publishers, the costs of switching to greener practices are currently high. Companies will need to invest in research, development and legislation of more sustainable practices. In order to reach CN, careful consideration needs to be given to what energy sources are used and environmental stewardship needs to be emphasized. Otherwise the U.S. printing system could collapse into itself. The below are just recommendations for publishers to start working towards greener practices. For examples of businesses already doing these practices look to: Cascades, Chelsea Green, Berrett-Koehler, Hemlock, Macmillan, Patagonia, and Rolland Sustana Group [ 14 , 15 ].

Findings and Recommendations

Start with paper: pcw, paper weights, prices, and print-on-demand.

As mentioned above, paper is one of the largest contributors to waste and power consumption. Paper weight should also be considered [ 16 ], as Macmillan reported significant savings by choosing a lighter paper weight. In addition to paper type/weight, Patagonia recommends trim size should be considered. One may also consider raising book prices to accommodate this. Another way to minimize the use of paper is to utilize POD options rather than running large print runs.

Assess Your Own Emissions

For those who are unsure of where to start, a climate change firm can be hired to assess what areas of the company are producing the highest carbon emissions. If this is too expensive, there are also excellent resources available to help publishers calculate their own emissions [ 17 ] (in bibliography).

Cost-Effective Book Delivery

To determine cost-effective book delivery practices, this question was addressed: as consumer buying habits further migrate from retail to online, what does efficient and cost-effective delivery of print books to readers look like going forward?

Currently, there are several selling and delivery models in book publishing, some of which were frequently used during pandemic lockdowns. Many publishers are finding ways to pull in more online direct-to-consumer sales or creating their own bookselling outlets. Additionally, as consumer buying habits further migrate from retail to online, organizations like Bookshop.org aim to create efficient ways for consumers to get their books and at the same time support bookstores.

Another cost-effective marketing tactic is to offer local delivery or pick up, when possible. In Washington D.C. Kramerbooks & Afterwords Cafe is claimed to be using an “unexpected source for book delivery”. Kramerbook uses Postmates, an app known for its traditional use of food delivery, to hand deliver books to readers in the D.C. area [ 18 ].

To address the supply chain issues discussed in the introduction, publishers, especially smaller publishers, will want to increase advance demand on new titles in order to get high levels of engagement with delivery postponement offers [ 19 ]. Delivery postponement in publishing translates to pre-orders for frontlist titles. Essentially, publishers will need to push pre-orders especially hard and make clear in the marketing that if one does not pre-order a new title, they may have to wait longer for it to be back in stock. This pre-order process would allow publishers to have a POD run for pre-orders that they could then advertise as having sold out, further stimulating interest in the book. Having quantities pre-ordered by consumers will allow publishers to order appropriately sized print runs that will decrease shipping costs and potential returns. By using this method, publishers will be able to make print book delivery more cost-effective from a manufacturing as well as a shipping standpoint.

Local and Discounted Delivery

Publishers can make more active contributions toward promoting local delivery among independent booksellers, and programs like Hachette’s with a discount for delivery is a start. Offering discounts to booksellers or consumers for local deliveries would incentivize more local retailers to offer delivery services if they do not already. Or publishers can go the route of creating their own online retailer and partner with a distributor and investors. This would be the least cost-effective to start but could result in delivery times that rival large retailers as seen through BookBook or in exclusive content to draw in your readers in the case of Inverso.pl.